Chester Carlson facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Chester Floyd Carlson

|

|

|---|---|

| Born | February 8, 1906 Seattle, Washington, United States

|

| Died | September 19, 1968 (aged 62) New York City, New York, United States

|

| Citizenship | United States of America |

| Alma mater | San Bernardino High School Riverside Junior College California Institute of Technology New York Law School |

| Known for | Invention of xerography |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Electrophotography / Xerography |

| Institutions | Bell Labs Battelle Memorial Institute Xerox |

Chester Floyd Carlson (born February 8, 1906 – died September 19, 1968) was an American physicist, inventor, and patent attorney. He was born in Seattle, Washington.

Carlson invented a special way of copying called electrophotography. Today, we call it xerography, which means "dry writing." This method makes a dry copy, unlike older ways that used wet chemicals. Millions of photocopiers around the world use his invention every day.

Contents

Chester's Early Life

Chester Carlson started working at a very young age to help his family. He said, "Working outside of school hours was a must. I used my free time to invent things, experiment, and plan for the future." He was inspired by inventors like Thomas Edison and wanted to create something useful. He also hoped it would improve his family's financial situation.

Carlson's father, Olaf, became very sick with tuberculosis and later arthritis. His mother, Ellen, also got sick with malaria. Because of their illnesses, Chester's family was very poor. He began doing odd jobs for money when he was just eight years old. By age thirteen, he worked before and after school. In high school, he was the main person supporting his family. His mother died when he was 17, and his father died when he was 27.

Chester started thinking about how to copy things when he was young. At age ten, he made a handwritten newspaper called This and That for his friends. He loved his rubber stamp printing set and a toy typewriter he got for Christmas.

While working for a local printer in high school, he tried to make a magazine for science students. He quickly found traditional printing methods frustrating. He later said, "That made me think about easier ways to do it. I started thinking about duplicating methods."

Chester's Education Journey

Chester loved graphic arts from childhood. He wanted a typewriter even in elementary school. In high school, he enjoyed chemistry and wanted to publish a magazine for young chemists. He worked for a printer, who sold him an old printing press. He tried to print his own paper but found it very difficult. This experience made him think deeply about how hard it was to get words onto paper. He started an inventor's notebook to jot down ideas.

Because he worked so much to support his family, Carlson had to take an extra year at San Bernardino High School. Then, he joined a work-study program at Riverside Junior College. He worked and went to classes in alternating six-week periods. He had three jobs at Riverside, paying for a small apartment for himself and his father. He started studying chemistry but switched to physics because of a favorite professor.

After three years, Chester transferred to the California Institute of Technology, or Caltech. This had been his dream since high school. The tuition was expensive, and he couldn't earn much money while studying. He mowed lawns and did odd jobs on weekends. By the time he graduated in 1930, he was $1,500 in debt. This was at the start of the Great Depression, so finding a job was very hard. He applied to 82 companies but didn't get any job offers.

Starting His Career

Carlson felt there was a great need for a fast, good copying machine that could be used right in an office. He said, "There seemed such a crying need for it—such a desirable thing if it could be obtained. So I set out to think of how one could be made."

He finally got a job at Bell Telephone Laboratories in New York City as a research engineer. He found the work boring, so after a year, he moved to the patent department. There, he helped one of the company's patent lawyers.

Carlson wrote down over 400 ideas for new inventions in his notebooks while at Bell Labs. He kept returning to his interest in printing. His job in the patent department made him even more determined to find a better way to copy documents. He often needed copies of patent papers and drawings, but there was no easy way to get them. Back then, copies were usually made by typists retyping everything with carbon paper. Other methods like mimeographs were expensive or had other problems. These were "duplicating" machines, meaning you had to create a special master copy first. Carlson wanted a "copying" machine that could copy an existing document directly.

In 1933, during the Great Depression, Carlson lost his job at Bell Labs. After looking for six weeks, he found a job at Austin & Dix, a firm near Wall Street. He left about a year later because the firm's business was slowing down. He then got a better job at P. R. Mallory Company, an electronics firm, where he became the head of the patent department.

Inventing Electrophotography

In 1936, Carlson began studying law at night at New York Law School. He got his law degree in 1939. He studied at the New York Public Library, copying long sections from law books by hand because he couldn't afford to buy them. This hard work made him even more determined to invent a true copying machine. He started visiting the library's science and technology section. There, he found a short article by a Hungarian physicist named Pál Selényi. This article gave him an idea for his dream machine.

Carlson's first experiments were in his apartment kitchen. They were often smoky, smelly, and sometimes even explosive! In one experiment, he tried melting sulfur onto a zinc plate over his stove. This often caused sulfur fires, filling the building with a smell like rotten eggs. Another time, his chemicals caught fire, and he and his wife had to quickly put out the flames.

During this time, he also developed arthritis in his spine, like his father. But he kept going with his experiments, his law studies, and his regular job.

Carlson knew how important patents were from his work as a patent clerk and lawyer. So, he patented his ideas every step of the way. He filed his first patent application on October 18, 1937.

By the fall of 1938, Carlson's wife convinced him to move his experiments out of their home. He rented a room in Astoria, Queens. He hired an assistant named Otto Kornei, a physicist who was out of work.

Carlson knew that big companies were also trying to find ways to copy paper. Companies like Haloid Company and Eastman Kodak were working on photographic methods. These methods needed special chemicals and papers. For example, the Photostat machine basically took a photograph of the document.

How Electrophotography Works

Selényi's article described a way to print images using a beam of charged particles on a spinning drum. These particles would create an electric charge on the drum. Then, a fine powder could be sprinkled on the drum. The powder would stick to the charged parts, much like a balloon sticks to something with static electricity.

Before this, Carlson had tried to make an electric current in the original paper using light. Selényi's article gave him a new idea: use light to *remove* the static charge from a special material called a photoconductor. The black marks on the paper wouldn't reflect light, so those areas on the photoconductor would stay charged and hold the powder. He could then transfer this powder to a new sheet of paper, making a copy. This method was better than the Photostat, which only made a photographic negative.

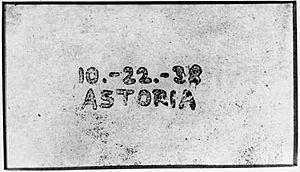

On October 22, 1938, Chester and Otto had their big breakthrough. Kornei wrote "10.-22.-38 ASTORIA." in ink on a glass microscope slide. He prepared a zinc plate coated with sulfur. In a dark room, he rubbed the sulfur with a cotton cloth to give it an electrostatic charge. Then, he placed the slide on the plate and shined a bright light on it. They removed the slide, sprinkled lycopodium powder on the sulfur, gently blew away the extra powder, and then transferred the image to a sheet of wax paper. They heated the paper to make the wax soft so the powder would stick. This was the world's first xerographic copy! After repeating the experiment to be sure, Carlson took Kornei out for a simple lunch to celebrate.

Kornei wasn't as excited as Carlson. Within a year, he left Carlson. He didn't believe electrophotography would be a big success. He even gave up his agreement to get 10% of Carlson's future earnings from the invention. Years later, when Xerox stock was worth a lot, Carlson sent Kornei 100 shares of the company as a gift. If Kornei had kept that gift, it would have been worth over $1 million by 1972!

Carlson faced many rejections. More than twenty companies turned him down for funding between 1939 and 1944. He tried to sell his invention to IBM, a big office equipment company, but they didn't see its value. He even met with the U.S. Navy, who were interested in dry copies, but they didn't understand his vision either.

On October 6, 1942, the Patent Office officially gave Carlson his patent for electrophotography.

Working with Battelle Memorial Institute

When Carlson was about to give up, he got a lucky break. In 1944, Russell W. Dayton, an engineer from the Battelle Memorial Institute in Ohio, visited Carlson's workplace. Dayton seemed interested in new ideas. Carlson showed him his invention. Dayton understood its importance, telling other scientists, "However crude this may seem, this is the first time any of you have seen a reproduction made without any chemical reaction and a dry process."

Battelle decided to take a chance on Carlson's invention. Dr. Harold E. Clark from Battelle said, "Electrophotography had almost no scientific background. Chet put together many different ideas, none of which had been connected before. The result was the biggest thing in imaging since photography itself."

By 1945, Battelle agreed to help Carlson with his patents, pay for more research, and develop the idea. Battelle tried to get big printing and photography companies like Eastman Kodak to use the idea, but they weren't interested.

Partnering with Haloid Company

The big commercial breakthrough happened when John H. Dessauer, head of research at the Haloid Company, read an article about Carlson's invention. Haloid made photographic paper and wanted to find a new product to stand out from its big neighbor, Eastman Kodak. Dessauer thought electrophotography could help Haloid enter a new market that Kodak didn't control.

In December 1946, Battelle, Carlson, and Haloid signed their first agreement. Haloid paid $10,000 for the right to make copying machines based on electrophotography. Both sides were a bit unsure. Battelle worried about Haloid's small size, and Haloid worried if electrophotography would really work.

During this time, Battelle did most of the basic research, while Haloid focused on making a product. In 1948, Haloid's CEO, Joseph Wilson, convinced the U.S. Army Signal Corps to invest $100,000 in the technology. The Signal Corps was worried about nuclear war. Traditional photographic film could be ruined by radiation, but they thought electrophotography might be immune. For much of the 1950s, government contracts paid for over half of Battelle's research into electrophotography.

In 1947, Carlson worried that Battelle wasn't developing his invention fast enough. His patent would expire in ten years. After meeting with Joe Wilson, Carlson agreed to become a consultant for Haloid. He and his wife, Dorris, moved to Rochester, New York, where Haloid was located.

After trying for years to get other companies interested, Battelle agreed to make Haloid the only company allowed to use Carlson's invention (except for a few small uses Battelle kept for itself).

The Rise of Xerox

Chester Carlson wrote to Joseph Wilson in 1953, saying, "What Bell is to the telephone—or, more fittingly, what Eastman is to photography—Haloid could be to xerography."

What is Xerography?

By 1948, Haloid knew it needed to announce electrophotography to the public. But the name "electrophotography" was a problem. It sounded too much like traditional photography. After looking at many options, Haloid chose a new name suggested by a classics professor: xerography. This word comes from Greek words xeros ("dry") and graphein ("writing"). Carlson didn't love the name, but Haloid's CEO, Joseph Wilson, did. The company's board voted to use it. The sales and advertising head, John Hartnett, decided not to trademark "xerography" because he wanted everyone to use the word freely.

The First Copier: XeroX Model A

On October 22, 1948, exactly ten years after that first copy was made, the Haloid Company publicly announced xerography. In 1949, they shipped their first commercial photocopier: the XeroX Model A Copier, also known as the "Ox Box." The Model A was hard to use, needing 39 steps to make one copy because most of the process was done by hand.

The product might have failed, but it turned out to be great for making paper masters for offset printing presses. Companies like Ford Motor Company bought the Model A for their printing departments. Before the Model A, making a paper master for printing was slow, expensive, and messy. The Model A's toner repelled water but attracted oil-based inks, making it easy to create a printing master. It cut the cost of making a master from three dollars to less than forty cents. Ford saved so much money that it was even mentioned in one of their annual reports!

After the Model A, Haloid released other xerographic copiers, but they were still not very easy to use. Meanwhile, competitors like Kodak and 3M released their own copying devices using different technologies. Kodak's Verifax, for example, was small and cost $100. Haloid's machines were more expensive and much bigger.

Haloid Xerox Becomes Xerox

In 1955, Haloid signed a new agreement with Battelle, giving Haloid full ownership of Carlson's xerography patents. In return, Battelle received 50,000 shares of Haloid stock. Carlson received 40% of the money and stock from this deal. That same year, a British film company called Rank Organisation was looking for new products. One of their leaders, Thomas A Law, found an article about Carlson's invention. Rank partnered with Haloid in a joint company called Rank Xerox to use the patents in Europe. As photocopying became popular worldwide, Rank's profits grew hugely.

Haloid needed to expand. In 1955, the company bought a large piece of land in Webster, New York. This site would become their main research and development campus.

Haloid's CEO, Joseph Wilson, wanted a new name for the company as early as 1954. After years of discussion, the board approved changing the name to "Haloid Xerox" in 1958. This showed that xerography was now the company's main business.

The Xerox 914: A Game Changer

The first machine that looked like a modern photocopier was the Xerox 914. It was still large, but it allowed someone to place an original document on a glass surface, press a button, and get a copy on plain paper. The 914 was launched in New York City on September 16, 1959. Even with some early problems (one demonstration unit caught fire!), the Xerox 914 was a huge success. Between 1959 and 1961, Haloid Xerox's earnings almost doubled.

The 914 was successful for several reasons: it was easy to use, it didn't damage the original document, and it used plain paper, which was cheaper than special paper. Haloid Xerox also decided to rent the 914 instead of selling it. It cost $25 per month, plus four cents per copy (with a minimum of $49 per month). This made it much more affordable than other copiers.

In 1961, because of the Xerox 914's success, the company changed its name again to Xerox Corporation.

For Carlson, the success of the Xerox 914 was the highlight of his life's work. It was a machine that could quickly and cheaply make an exact copy of any document. After the 914 started being made, Carlson became less involved with Xerox and began focusing on helping others.

Chester's Personal Life

In 1934, Carlson married Elsa von Mallon. They met at a YWCA party in New York City. Carlson described their marriage as "an unhappy period." They divorced in 1945.

Carlson married his second wife, Dorris Helen Hudgins, while the agreements between Battelle and Haloid were being made.

Later Life and Helping Others

U Thant, who was the secretary-general of the United Nations, spoke at Chester Carlson's memorial service. He said, "To know Chester Carlson was to like him, to love him, and to respect him. He was known as the inventor of xerography, but I respected him more as a man of great moral character and someone who cared deeply about humanity."

In 1951, Carlson's earnings from his patents were about $15,000. He continued to work at Haloid until 1955 and remained a consultant for the company until he died. From 1956 to 1965, he continued to earn royalties from Xerox, which was about one-sixteenth of a cent for every copy made worldwide.

In 1968, Fortune magazine listed Carlson as one of the wealthiest people in America. He sent them a short letter saying, "Your estimate of my net worth is too high by $150 million. I belong in the 0 to $50 million bracket." This was because Carlson had quietly given away most of his money for years. He told his wife his goal was "to die a poor man."

Carlson used his wealth to help many good causes. He donated over $150 million to charities and actively supported the NAACP. His wife, Dorris, got him interested in Hinduism and Zen Buddhism. They hosted Buddhist meetings and meditation at their home. They also helped fund the Rochester Zen Center and a Zen monastery in New York.

Carlson preferred to make his donations anonymously. However, he stayed in close contact with the researchers he supported. For example, he helped fund research into paranormal phenomena at the University of Virginia. He made annual donations and a very large donation in 1964 that helped create one of the first endowed professorships at the university.

In the spring of 1968, Carlson had his first heart attack while on vacation. He was very ill but hid it from his wife. He started making unexpected home improvements and secretly visited his doctor. On September 19, Carlson died of a heart attack. His wife arranged a small service, and Xerox held a much larger service in Rochester.

Chester Carlson's Legacy

Many organizations benefited from Carlson's generosity. The New York Civil Liberties Union received money from his will. The University of Virginia received $1 million specifically for parapsychology research. The Center for the Study of Democratic Institutions received over $4.2 million from Carlson after his death, in addition to the more than $4 million he had given while alive.

In 1981, Carlson was added to the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

On October 22, 1988, the United States recognized his contributions by naming it "National Chester F. Carlson Recognition Day." The United States Postal Service also honored him with a 21¢ postage stamp.

Buildings at two major universities in Rochester, New York (Xerox's hometown), are named after Carlson. The Chester F. Carlson Center for Imaging Science at the Rochester Institute of Technology studies things like remote sensing and xerography. The University of Rochester's Carlson Science and Engineering Library is the main library for science and engineering.

On October 25, 2019, New York City honored Carlson by officially co-naming 37th Street in Queens, New York, where his first makeshift lab was located, after him.

Several awards are named in Carlson's honor:

- American Society for Engineering Education: The Chester F. Carlson Award is given each year to an innovator in engineering education.

- Royal Swedish Academy of Engineering Science, IVA: The Chester Carlson Award recognizes important research in information science.

- Society for Imaging Science and Technology: The Chester F. Carlson Award recognizes excellent technical work that improves electrophotographic printing.

See also

In Spanish: Chester Carlson para niños

In Spanish: Chester Carlson para niños

- Copy art

- Photocopier

- Duplicating machines

- Thomas Edison

- David Gestetner

| Percy Lavon Julian |

| Katherine Johnson |

| George Washington Carver |

| Annie Easley |