Frederic Eugene Ives facts for kids

Frederic Eugene Ives (born February 17, 1856 – died May 27, 1937) was an inventor from the U.S.. He was born in Litchfield, Connecticut. From 1874 to 1878, he worked in the photography lab at Cornell University. Later, he moved to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. In 1885, he helped start the Photographic Society of Philadelphia. Ives won many awards for his inventions, including several from the Franklin Institute. His son, Herbert E. Ives, also became a famous inventor, known for his work in early television.

Color Photography Inventions

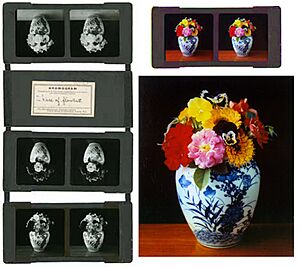

Frederic Eugene Ives was a very important person in the early days of color photography. He first showed his system for taking natural color photos in 1885 in Philadelphia. His special system, called the Kromskop (pronounced "chrome-scope"), became available to buy in England by late 1897 and in the U.S. about a year later.

Here is how his Kromskop system worked:

- He took three separate black-and-white pictures of something.

- Each picture was taken through a different colored filter: red, green, or blue.

- This idea of using colored filters to record color was first thought of by James Clerk Maxwell in 1855.

To see the colors, you would use Ives' Kromskop viewer. This device used special red, green, and blue filters and mirrors. It combined the three black-and-white images into one full-color picture. You could get Kromskop viewers for one eye or for 3D viewing. Special sets of pictures, called Kromograms, were sold to view in these devices. Ives also made a projector that could show these three images together on a screen in full color.

People who wanted to make their own Kromograms could buy special cameras from Ives. Even though the color quality was excellent, the Kromskop system was not a big success. It was a bit complicated to use. When the Autochrome process came out in 1907, which was much simpler, Ives' system was stopped.

In 2009, some Kromogram pictures taken by Ives were found. These pictures showed San Francisco just six months after the big earthquake and fire in 1906. They are thought to be the only natural color photos of that disaster. This means the colors were captured by the camera, not added by hand later. They are also the oldest natural color photos of San Francisco.

Creating 3D Images

In 1903, Ives received a patent for something called the parallax stereogram. This was the first way to see 3D images without needing special glasses!

Here's how it worked:

- He made a special image by combining tiny vertical strips from two different pictures.

- When you looked at this combined image through a grid of thin, opaque lines (called a parallax barrier), each eye saw only the strips meant for it. This made the image appear in 3D.

Ives first showed this idea in 1901. He said he thought of the basic idea about 16 years earlier. Later, other inventors, including Ives' son Herbert, improved this idea. They used tiny lenses instead of a grid. This led to the 3D images you might see on postcards or trading cards today. The original parallax barrier method is still used in some 3D video displays that don't need glasses.

Ives also patented using these parallax barriers to show images that could change.

As early as 1900, Ives was experimenting with 3D movies. By 1922, he and another inventor, Jacob Leventhal, made popular 3D short films called Plastigrams. These were shown using anaglyph technology, which means you needed red and cyan (blue-green) glasses to see the 3D effect.

The Halftone Printing Process

Halftone processes are super important for printing photographs in books and newspapers. Before this, pictures were printed using hand-carved metal plates or wood blocks. These could only print solid lines or dots, not smooth shades of gray or color.

Sometimes, people say Ives invented "the" halftone process, but that's not quite right. Ives himself never claimed this. There wasn't just one halftone process; many different ones were developed over time. The very first attempts were almost as old as photography itself, starting around 1839. However, these early methods were often too difficult, too expensive, or didn't produce good enough quality for widespread printing.

Ives started working on halftone processes in the late 1870s. His goal was to find a way to automatically turn the smooth shades of a photograph into tiny black-and-white dots or lines. These dots or lines needed to be small enough that your eyes would blend them together from a normal viewing distance, making you see different shades of gray. Also, the printing plates had to be strong enough to print many copies without wearing out. Most importantly, the process had to be cheap enough for businesses to use widely.

Ives patented his first "Ives' process" in 1881. This process was a bit complicated, but it was simpler and more effective than other methods used at the time. In 1884, Ives said it was "the first patented or published process which was introduced into truly successful commercial operation."

A few years later, Ives created a much simpler process, which is often linked to his name. In this new method:

- An ordinary photograph was directly re-photographed onto a metal plate that was sensitive to light.

- He used a special "crossline screen" (two glass plates with fine lines crossing each other) placed near the metal plate.

- He also used a specially shaped opening in the camera lens.

These tools helped break the image into a regular pattern of dots of different sizes and shapes. During the 1890s, photographs printed using this second "Ives process" largely replaced older hand-engraved pictures. It became the standard way to print photos in books, magazines, and newspapers for the next 80 years. Even though printing technology has changed a lot, the basic way most printed halftone images look is still very similar to what Ives developed.

See also

In Spanish: Frederic Eugene Ives para niños

In Spanish: Frederic Eugene Ives para niños

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |