Knossos facts for kids

|

Κνωσσός

|

|

| Lua error in Module:Wikidata at line 70: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value).

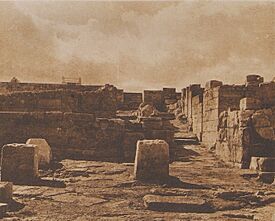

Reconstructed North Entrance

|

|

Map of Crete

|

|

| Location | Heraklion, Crete, Greece |

|---|---|

| Region | North central coast, 5 km (3.1 mi) southeast of Heraklion |

| Coordinates | 35°17′53″N 25°9′47″E / 35.29806°N 25.16306°E |

| Type | Minoan palace |

| Area | Total inhabited area: 10 km2 (3.9 sq mi). Palace: 14,000 m2 (150,000 sq ft) |

| History | |

| Founded | Settlement around 7000 BC; first palace around 1900 BC |

| Abandoned | Palace abandoned Late Minoan IIIC, 1380–1100 BC |

| Periods | Neolithic to Late Bronze Age |

| Cultures | Minoan, Mycenaean |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1900–present |

| Archaeologists | Minos Kalokairinos, Sir Arthur Evans, David George Hogarth, Duncan Mackenzie, Theodore Fyfe, Christian Doll, Piet de Jong, John Davies Evans |

| Condition | Restored and maintained for visitation. |

| Management | 23rd Ephorate of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities |

| Public access | Yes |

Knossos (pronounced Koh-NOH-sos) is an amazing ancient site on the island of Crete in Greece. It was a very important city during the Bronze Age, home to the powerful Minoan civilization. Many people believe Knossos is the oldest city in all of Europe!

This famous place is known for the huge Palace of Minos. This palace was not just a king's home. It was a busy center for religion and government. The first parts of the palace were built around 1900 BC. It grew and changed over many centuries.

Knossos is also famous for its connection to the exciting Greek myth of Theseus and the scary Minotaur. Today, it's a popular spot for tourists near Heraklion.

Archaeologists started digging here in 1877. Later, in 1900, Sir Arthur Evans led big excavations. He uncovered most of the palace and found incredible treasures. These include the famous Bull-Leaping Fresco and Linear B tablets. Evans helped us learn a lot about the Minoan civilization. However, some of his reconstructions of the palace are now seen as controversial.

Contents

Discovering Ancient Knossos

Life in the Neolithic Period

Knossos was first settled around 7000 BC. This makes it the oldest known settlement on Crete. The first villagers were a small group of 25 to 50 people. They lived in simple huts made of mud and branches. These early settlers raised animals and grew crops. They also buried their children under the floors of their homes. This shows a continuous use of the area for special activities.

Over time, the village grew much larger. By 6000–5000 BC, hundreds of people lived there. Their houses were square, made of mud-brick walls on stone bases. The roofs were flat, made of mud over branches. They had hearths (fireplaces) in the center of their main rooms. One special house had eight rooms, suggesting it might have been used for storage.

By 5000–4000 BC, the population reached up to 1000 people. Homes became more private. A large stone house, called the Great House, was built. It had thick walls, possibly for a second story. This house might have been a public building, a very early form of a palace. The population kept growing a lot during this time.

The Bronze Age and Minoan Palaces

Around 2000 BC, the first grand palaces were built on Crete. Knossos, Malia, Phaestos, and Zakro all had them. These palaces were a big change from simple village life. They showed that people had more wealth and stronger leaders. These leaders were important for both government and religion.

The early palaces were destroyed around 1700 BC. Earthquakes, which are common in Crete, likely caused this. But the people quickly rebuilt them, even grander than before! This period, from about 1650 to 1450 BC, was the peak of Minoan power. All palaces had large central courtyards. These courtyards were probably used for public events and shows. Around the court were living areas, storage rooms, and offices. There were also workshops for skilled craftspeople.

The Palace of Knossos was the biggest of them all. Its main building covered three acres. With other buildings, it spread over five acres! It had a grand staircase leading to important rooms upstairs. A special religious center was on the ground floor. The palace had sixteen storage rooms filled with huge jars called pithoi. These jars, up to five feet tall, held oil, wine, wool, and grain. The palace even had bathrooms, toilets, and a drainage system! A theater at Knossos could hold 400 people. It was likely used for religious dances.

Minoan builders used stone for foundations and a timber frame for the main structure. Walls were made of large, unbaked bricks. Flat roofs were covered with clay. Light-wells and wooden columns made rooms bright. The walls were decorated with beautiful frescoes. These paintings showed daily life and processions. They rarely showed warfare. Women in the frescoes wore elaborate hairstyles and long, flowing dresses. Their clothing styles were unique for the time.

Knossos became rich by using Crete's resources like oil, wine, and wool. Trade also helped it grow. Minoan pottery has been found in Egypt, Syria, and other places. Knossos had strong connections with islands like Rhodes and Samos. Cretan influence even appeared in early writings from Cyprus.

Around 1450 BC, other palaces on Crete were destroyed. Knossos became the only major palace left. During this time, people from mainland Greece, called Mycenaeans, may have taken control. Greek became the main language. The art and architecture also started to look more like Mycenaean styles.

Around 1350 BC, the Palace of Knossos was destroyed by a fire. The upper floors collapsed. We don't know if this was an accident or if enemies caused it. The palace was never fully rebuilt. Even though the town of Knossos continued to exist, the grand palace was gone forever.

Knossos in Later Times

After the Bronze Age, people still lived in Knossos. By 1000 BC, it was again an important center on Crete. It had two ports, one at Amnisos and another at Heraklion.

Knossos was involved in many alliances and wars with other cities. For example, in 343 BC, it teamed up with Philip II of Macedon. Later, in the third century BC, Knossos became very powerful on the island. However, other cities and the Macedonian king Philip V stopped its expansion.

With help from the Romans, Knossos became the leading city of Crete again. But in 67 BC, the Romans made Gortys the capital of their new province. In 36 BC, Knossos became a Roman colony called Colonia Iulia Nobilis. Roman-style buildings were built near the old palace.

Roman coins found at the site helped identify Knossos. Many coins showed the word "Knosion" or "Knos" and images of the Minotaur or Labyrinth. The Romans believed they were the first to settle Knossos.

Knossos in Modern History

Knossos became a religious center in 325 AD. Later, in the 9th century, people moved to a new town called Chandax (modern Heraklion). By the 13th century, the old site was known as 'Long Wall'.

Today, the name Knossos refers only to the archaeological site. Arthur Evans did extensive excavations here in the early 1900s. The site was even used as a military headquarters during World War II. Knossos is now part of the growing suburbs of Heraklion. In 2025, UNESCO recognized Knossos as a World Heritage Site.

Exciting Legends of Knossos

In Greek mythology, the mighty King Minos lived in a palace at Knossos. He asked the clever inventor Daedalus to build a labyrinth. This was a huge, confusing maze designed to hold the terrifying Minotaur. Daedalus also built a special dancing floor for Queen Ariadne.

The word labyrinth might be connected to ancient Crete. The symbol of the double axe, called a labrys, was found all over the palace. This symbol was thought to protect objects. Axes were carved into many stones and appeared in art.

The most famous legend is about Theseus, a prince from Athens. His father was King Aegeus, which is how the Aegean Sea got its name. Theseus sailed to Crete to fight the Minotaur. This creature was half-man, half-bull. King Minos kept the Minotaur in the Labyrinth.

King Minos's daughter, Ariadne, fell in love with Theseus. Before he entered the maze, she gave him a ball of thread. Theseus unwound the thread as he went deeper into the Labyrinth. This way, he could find his way back out. Theseus bravely killed the Minotaur. Then, he and Ariadne escaped from Crete, away from her angry father.

Knossos also appears in other old stories. The historian Herodotus wrote that King Minos created a powerful sea empire. Thucydides added that Minos cleared the seas of pirates. He also increased trade and started colonies on many Aegean islands. Another legend tells of Rhadamanthus, a wise lawgiver from Crete. He is said to have created traditions like ancient Greek gymnasiums.

Digging Up the Past

The site of Knossos was first identified by Minos Kalokairinos. He dug up parts of the West Wing in 1878-1879. Then, the British archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans (1851–1941) and his team began much larger excavations. They worked from 1900 to 1913, and again from 1922 to 1930.

Evans was surprised by how big the palace was. He also discovered two ancient writing systems. He called them Linear A and Linear B. These were different from the picture-like writings also found. By studying the layers of the palace, Evans developed the idea of the Minoan civilization. He named it after the legendary King Minos.

Since their discovery, the ruins have been a focus of archaeological work and tourism. The site was even used as a military headquarters during two world wars.

John Davies Evans (not related to Arthur Evans) later did more excavations. He focused on the very early Neolithic period at the palace.

Exploring the Palace Complex

The palace at Knossos was changed and updated many times. The palace you see today has features from different periods. It also includes modern reconstructions, some of which might not be perfectly accurate. So, the palace never looked exactly as it does now.

Palace Layout and Activities

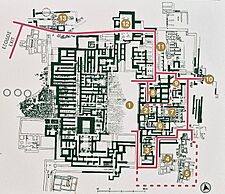

Like other Minoan palaces, Knossos was built around a rectangular central court. This court was longer from north to south. This design helped it get the most sunlight. Important rooms were also placed to face the rising sun.

The central court was likely used for special rituals and festivals. The Grandstand Fresco seems to show one of these ceremonies. Some experts think bull-leaping events happened here. However, others believe the court's surface and entrances weren't ideal for such a spectacle.

The palace covered about six acres. It included a theater and a main entrance on each of its four sides. There were also many large storerooms.

Where Knossos Was Built

The palace was built on Kephala Hill, about 5 km (3 miles) from the coast. Two streams, the Vlychia and the Kairatos, met nearby. These streams provided fresh drinking water for the ancient people. On the opposite side of the Vlychia stream was Gypsades Hill. The Minoans quarried gypsum, a soft mineral, from its eastern side.

Even though the town of Knossos surrounded it, Kephala Hill was not a fortress. It wasn't very high or steep, and it had no strong defenses.

The Royal Road is a remaining part of an ancient Minoan road. It connected the port to the palace. Today, a modern road, Leoforos Knosou, follows this ancient path.

Palace Storage Areas

The palace had many large storage rooms, called magazines. These held farm products like grain and oil. They also stored huge collections of high-quality tableware. Much of this pottery was made in other parts of Crete. Knossos pottery is famous for its unique styles and decorations. Archaeologists use these pottery styles to help date different parts of the palace.

Advanced Water Systems

The palace had at least three different water systems. One brought in fresh water. Another drained rainwater. The third carried away waste water.

Aqueducts brought fresh water to Kephala Hill. The water came from springs at Archanes, about 10 km (6 miles) away. These springs are the source of the Kairatos river. The aqueduct pipes were made of terracotta. They used gravity to deliver water to fountains and spigots. The pipes were designed to fit tightly together.

Waste water was carried away through a closed sewer system. The queen's megaron (main hall) had an early example of a flushing toilet. This toilet was a seat over a drain. Water from a jug was poured in to flush it. The nearby bathtub had to be filled by hand. It was probably drained by tipping it or bailing out the water. These special toilet and bath features were rare in the palace.

Heavy rains were common, so a runoff system was essential. It started with zigzag channels on flat surfaces. These channels had basins to slow down the water. Some parts of the system were covered, with manholes for access.

Keeping Cool: Ventilation

The palace was built on a hill, so it caught cool sea breezes in summer. It also had porticoes (covered walkways) and air shafts to help with air circulation.

Unique Minoan Columns

The palace features special Minoan columns. These are different from Greek columns. Minoan columns were made from cypress tree trunks. Greek columns are wider at the bottom and narrower at the top. This makes them look taller. But Minoan columns are wider at the top and narrower at the bottom. This is because the cypress trunk was inverted to prevent it from sprouting. The columns at Knossos were plastered, painted red, and had round, pillow-like tops called capitals.

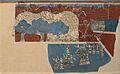

Colorful Frescoes

The palace at Knossos was very colorful, just like Greek buildings in ancient times. In the early periods, walls were painted a pale red. Later, white, black, blue, green, and yellow colors were added. These colors came from natural materials, like ground minerals. Outdoor paintings were done on fresh plaster with raised designs. Indoor paintings were on smooth, pure plaster.

The paintings showed scenes with people, mythical creatures, animals, and nature. Many of these images had special meanings. They likely related to the activities and rituals in each room. The earliest paintings copied designs found on pottery. Most frescoes have been put back together from many small pieces found on the floor. Sir Arthur Evans and his team used their skills to reconstruct these artworks. They used symmetry and templates to help. For example, male figures were often shown with darker skin than female figures.

Some archaeologists have questioned Evans' reconstructions. They argue that his work might have made the palace look more like modern art than it truly was.

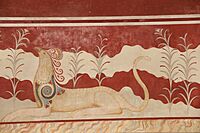

The Mysterious Throne Room

A very important room in the palace is called the Throne Room. It has a special seat made of alabaster built into the north wall. Sir Arthur Evans called this seat a "throne". There are also gypsum benches on three sides of the room. Next to the throne room is a feature called a lustral basin. Evans thought it was used for anointing rituals because he found perfume bottles there.

You entered the room from an anteroom through double doors. The anteroom connected to the central court. Both rooms are in a ceremonial area on the west side of the central court.

The throne is guarded by two griffins (mythical creatures with the body of a lion and head of an eagle). They are painted on the walls, lying down and facing the throne. Griffins were important symbols, also appearing on seal rings.

No one is completely sure how the Throne Room was used. Here are two main ideas:

- A King or Queen's Seat: This is the older idea from Evans. It suggests a priest-king or queen held court here. The griffins might have been a formal symbol of royalty. When the Mycenaeans took over Knossos around 1450 BC, they might have used this room for their rulers.

- A Goddess's Special Place: Another idea is that the room was for a goddess to appear. She might have sat on the throne as a statue, or a priestess might have sat there representing her. In this case, the griffins would be symbols of her divine power.

Famous People from Knossos

- Aenesidemus (first century BC), a philosopher who questioned knowledge.

- Chersiphron (sixth century BC), a famous architect.

- Epimenides (sixth century BC), a wise seer and poet.

- Ergoteles of Himera (fifth century BC), an Olympic runner who lived away from home.

- Metagenes (6th century BC), another architect.

- Minos (mythical), the legendary king and father of the Minotaur.

Images for kids

-

Knossos "kꜣnywšꜣ" depicted in the Temple of Amenhotep III at Kom el-Hatan.

-

A coin of Knossos, depicting a Labyrinth.

See also

In Spanish: Cnosos para niños

In Spanish: Cnosos para niños

- Magasa

- Trapeza

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |