History of newspaper publishing facts for kids

The modern newspaper was first invented in Europe. The very first handwritten news sheets, called Avvisi, were passed around in Venice, Italy, as early as 1566. These weekly sheets shared information about wars and politics across Italy and Europe. The first printed newspapers started appearing weekly in Germany in 1605. Governments often controlled what could be printed, especially in France. These early papers usually reported on news from other countries and current prices. After the English government allowed more freedom in 1695, newspapers became very popular in London and other cities like Boston and Philadelphia. By the 1830s, new fast printing machines could make thousands of papers cheaply, making them affordable for everyone.

Contents

Early Newspapers (1500s to 1800s)

Avvisi, also known as gazettes, were a big deal in Venice in the mid-1500s. They came out every week on single sheets folded into four pages. These publications reached many more people than earlier handwritten news. Their regular schedule and format greatly influenced how newspapers look today. The idea of a weekly, handwritten news sheet spread from Italy to Germany and then to Holland.

The First Printed Papers

The word "newspaper" became common in the 1600s. However, in Germany, publications that we would now call newspapers appeared even earlier, in the 1500s. They were considered newspapers because they were printed, dated, came out regularly, and included many different news stories. Before these, there were "trade fair reports" that came out twice a year for big book fairs in Germany, starting in the 1580s.

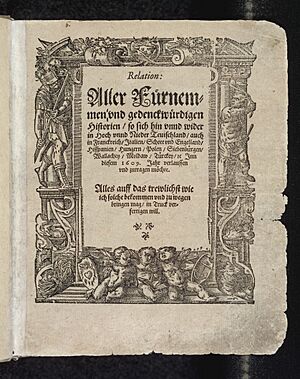

Still, the German-language Relation aller Fürnemmen und gedenckwürdigen Historien, printed from 1605 by Johann Carolus in Strasbourg, is widely thought to be the first true newspaper. This new way of sharing news grew because the printing press had spread. As historian Johannes Weber said, "At the same time... as the printing press in the physical, technological sense was invented, 'the press' in the extended sense of the word also entered the historical stage."

Other early papers include the Dutch Courante uyt Italien, Duytslandt, &c., started by Caspar van Hilten in 1618. This Amsterdam newspaper was the first to be printed in a larger "folio" size instead of the smaller "quarto" size. Amsterdam was a center for world trade, so it quickly became home to many foreign newspapers.

In 1618, the Wöchentliche Zeitung aus mancherley Orten (Weekly news from many places) began in Gdańsk, Poland. This was the oldest newspaper in Poland and the Baltic Sea region. Even though it was called "weekly," it often came out at irregular times, sometimes even three times a week.

The first English-language newspaper, Corrant out of Italy, Germany, etc., was published in Amsterdam in 1620. About a year and a half later, Corante, or weekely newes from Italy, Germany, Hungary, Poland, Bohemia, France and the Low Countreys. was published in England.

The first newspaper in France, La Gazette, was published in 1631. Portugal's first newspaper, A Gazeta da Restauração, came out in 1641 in Lisbon. Spain's first newspaper, Gaceta de Madrid, was published in 1661.

Post- och Inrikes Tidningar from Sweden, first published in 1645, is the oldest newspaper still in existence. However, it now only publishes online.

Merkuriusz Polski Ordynaryjny was published in Kraków, Poland, in 1661.

The first successful English daily newspaper, The Daily Courant, was published from 1702 to 1735. Its first editor, for 10 days in March 1702, was Elizabeth Mallet, who had run her late husband's printing business for years.

News was often chosen carefully and sometimes used to promote certain ideas. Readers liked exciting stories, such as accounts of magic, public events, and disasters. These kinds of stories were not seen as a threat to the government.

Newspapers in Germany

Even though printing with movable type was invented in China, Germany was the first European country to invent it on its own. The world's first newspapers were also produced in German states.

In the 1500s, a German financier named Fugger received not only business news but also exciting and gossip news from his contacts. This shows that early news publications mixed facts with interesting stories. Germany in the 1500s also had handwritten news that people paid to receive. Subscribers were usually lower-level government officials and merchants who could afford the somewhat expensive fee.

In the 1500s and 1600s, many printed news sheets appeared, summarizing battles, treaties, news about the king, diseases, and special events. In 1605, Johann Carolus published the first regular newspaper in Straßburg, with short news updates. The world's first daily newspaper appeared in 1650 in Leipzig. Later, Prussia became a very powerful German state, but its newspapers were tightly controlled. Advertising was not allowed, and budgets were very small.

Newspapers in Italy

The first Italian gazettes appeared in the early 1600s. Scholars believe the first newspaper printed in Italy was in Florence in 1636, but no copies have been found. The first confirmed Italian printed newspaper, Genova, was published in Genoa from 1639 to 1646. The copy from July 29, 1639, is the oldest Italian printed newspaper still existing. Similar papers were published in Rome (1640), Milan and Bologna (1642), and Torino (1645). These papers were mostly four-page weeklies and usually had no special titles, just the date and place of publication on the first page.

Newspapers in the Netherlands

Dutch "corantos" had a special look. They replaced the heavily illustrated German title page with a simple heading at the top of the first page, called a masthead, which is common today. These Dutch papers used space very well for text. They had two columns of text that covered almost the whole page, unlike earlier German papers that had only one column with wide margins. This more efficient use of space also meant fewer blank lines and minimal paragraph breaks. Different news stories were only separated by a slightly larger heading that usually showed the city or country the news came from. Another feature of corantos was their size: they were the first newspapers to be printed in a large "folio" size instead of "halfsheet." An example is the Opregte Haarlemsche Courant, first published in 1656. It still exists today, though in a smaller "tabloid" format.

British Newspapers

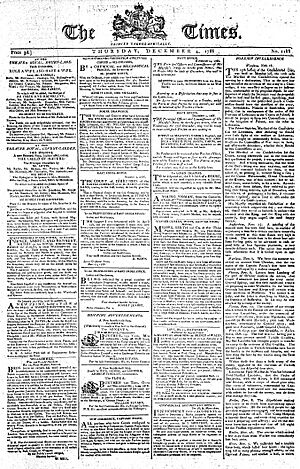

On November 7, 1665, The London Gazette (first called The Oxford Gazette) began publishing. It changed the look of English news printing, using two columns, a clear title, and a clear date, similar to the Dutch corantos. It was published twice a week. Other English papers soon started publishing three times a week, and then the first daily papers appeared.

Newspapers usually had short articles, temporary topics, some pictures, and classified ads. They were often written by many different authors, whose names were usually kept secret. They started to include some advertisements and did not yet have separate sections. Papers for a wider audience appeared, including Sunday papers for workers to read in their free time. The Times newspaper used new technologies and set high standards for other papers. This newspaper covered major wars and other big events.

Newspapers in North America

In Boston in 1690, Benjamin Harris published Publick Occurrences Both Forreign and Domestick. This is seen as the first newspaper in the American colonies, even though only one issue was printed before officials stopped it, possibly due to government control. It had a two-column format and was a single sheet printed on both sides.

In 1704, the governor allowed The Boston News-Letter, a weekly paper, to be published. It became the first newspaper in the colonies to be published continuously. Soon after, weekly papers began in New York and Philadelphia. The second English-language newspaper in the Americas was the Weekly Jamaica Courant. These early papers followed the British style and were usually four pages long. They mostly carried news from Britain, and their content depended on what the editor found interesting. In 1783, the Pennsylvania Evening Post became the first American daily newspaper.

In 1751, John Bushell published the Halifax Gazette, the first Canadian newspaper.

Newspapers in India

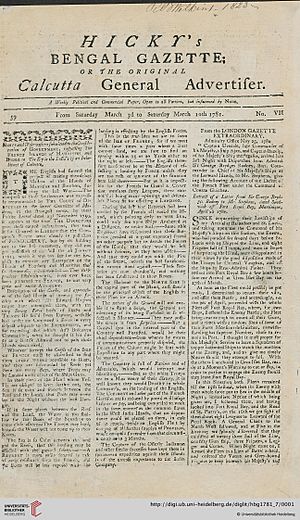

In 1766, a Dutch adventurer named William Bolts wanted to start a newspaper for the English people in Calcutta. But the East India Company sent him away before he could.

In January 1780, James Augustus Hicky published Hicky's Bengal Gazette, the first newspaper in India. This four-page paper was 12 by 8 inches. Hicky accused members of the East India Company, including Governor General Warren Hastings, of bad behavior. In response, Hastings stopped the post office from carrying Hicky's Bengal Gazette and later sued Hicky. In November 1780, the India Gazette appeared, which supported the Company government.

Modern Newspapers (Since 1800)

New Technology

In 1814, The Times newspaper got a new printing press that could print 1,100 pages per hour. It was soon changed to print on both sides of a page at once. This invention made newspapers cheaper and available to more people. In 1830, the first "penny press" newspaper came out: Lynde M. Walter's Boston Transcript. Penny papers cost about one-sixth the price of other newspapers and appealed to a wider audience. Newspaper editors shared copies and freely reprinted stories. By the late 1840s, telegraph networks connected cities, allowing news to be reported overnight. The invention of wood pulp papermaking in the 1840s greatly lowered the cost of newsprint, which used to be made from rags. More people learning to read in the 1800s also helped newspapers reach bigger audiences.

News Agencies

Only a few large newspapers could afford to have reporters in other cities. Instead, they relied on news agencies, which started around 1859. Important ones included Havas in France, the Associated Press in the United States, and Agenzia Stefani in Italy. Former Havas employees started Reuters in Britain and Wolff in Germany. Havas is now called Agence France-Presse (AFP). For international news, these agencies shared their resources. For example, Havas covered the French Empire, South America, and the Balkans, and shared that news with other national agencies. These major news agencies always aimed to provide fair and factual news to all their subscribers. They did not offer different news for conservative or liberal newspapers.

Newspapers in Britain

As more people learned to read, the demand for news grew quickly. This led to changes in newspaper size, appearance, heavy use of war reporting, a lively writing style, and a focus on fast reporting thanks to the telegraph. London newspapers led the way before 1870, but by the 1880s, London papers started to copy the new style of journalism from New York.

By the early 1800s, there were 52 papers in London and over 100 other titles. In 1802 and 1815, the tax on newspapers increased. Many untaxed newspapers appeared between 1831 and 1835 because people couldn't or wouldn't pay this fee. Most of these papers had strong, revolutionary ideas. Their publishers were arrested, but this didn't stop them. Eventually, in 1836, the tax was lowered, and in 1855, it was removed completely. After the tax reduction in 1836, the number of English newspapers sold jumped from 39 million to 122 million by 1854. This trend was further helped by better train transportation and telegraph communication, along with more people being able to read.

The Times Newspaper

The Times newspaper began in 1785 and was renamed in 1788. In 1817, Thomas Barnes became the editor. He was a strong supporter of press freedom. Under Barnes and his successor, John Thadeus Delane, the influence of The Times grew greatly, especially in politics. It pushed for reforms. The paper was the first in the world to reach a huge number of readers because it quickly adopted the steam-powered rotary printing press. It was also the first truly national newspaper, as it was distributed by the new steam railways to growing cities across the country. This helped the paper make money and become more influential.

The Times was the first newspaper to send reporters to cover wars. W. H. Russell, the paper's reporter during the Crimean War in the mid-1850s, wrote very important reports. For the first time, the public could read about the real difficulties of war. For example, on September 20, 1854, Russell wrote about a battle, pointing out the lack of care for wounded soldiers. People were shocked and angry, which led to major reforms. The Times became known for its influential editorials (opinion pieces).

Other Main British Papers

The Manchester Guardian was started in Manchester in 1821 by a group of business people. Its most famous editor, Charles Prestwich Scott, made the Guardian a world-famous newspaper in the 1890s.

The Daily Telegraph began on June 29, 1855. It was bought by Joseph Moses Levy the next year, who made it the first penny newspaper in London. His son, Edward Lawson, soon became editor. It became a way to understand middle-class opinions and claimed the largest number of readers in the world by 1890.

New Journalism of the 1890s

The "New Journalism" aimed at a popular audience, not just the wealthy. William Thomas Stead was a very important journalist and editor who started investigative journalism. Stead's "new journalism" helped create the modern tabloid newspaper. He showed how the press could influence public opinion and government decisions. He also wrote a lot about child welfare and social reforms.

Stead became assistant editor of the Pall Mall Gazette in 1880. He changed this traditional newspaper by adding maps and diagrams for the first time, breaking up long articles with catchy subheadings, and mixing his own opinions with those of people he interviewed. He also created news events instead of just reporting them, like his famous investigation into the Eliza Armstrong case.

Northcliffe's Changes

The early 1900s saw the rise of popular journalism. These papers were for people with lower to middle incomes. They focused less on detailed news analysis and more on sports, crime, exciting stories, and celebrity gossip. Alfred Harmsworth, 1st Viscount Northcliffe, was the main innovator. He used his Daily Mail and Daily Mirror to change the media, similar to the "Yellow Journalism" style in America. Lord Beaverbrook called him "the greatest figure who ever strode down Fleet Street" (Fleet Street was famous for newspapers). Experts say he "shaped the modern press" by introducing broad content, using advertising to lower prices, and marketing aggressively.

British Newspapers Between the World Wars

After World War I, major newspapers competed fiercely for readers. Political parties, which used to have their own papers, couldn't keep up, and their papers were sold or closed. Selling millions of copies depended on popular stories with strong human interest, as well as detailed sports reports. Serious news was for a smaller group of readers and didn't add much to sales. This niche was dominated by The Times and The Daily Telegraph. Many local daily papers were bought up and added to large chains based in London.

The Times of London was long the most respected newspaper, even though it didn't have the most readers. It focused much more on serious political and cultural news. In 1922, John Jacob Astor bought The Times. The paper supported the idea of "appeasement" towards Hitler's demands. Its editor, Geoffrey Dawson, was close to Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain and strongly pushed for the Munich Agreement in 1938. News reports from Berlin that warned of war were changed in London to support appeasement. However, in March 1939, the paper changed its mind and called for urgent war preparations.

Newspapers in Denmark

Danish news media started in the 1540s with handwritten news sheets. In 1666, Anders Bording, known as the father of Danish journalism, began a state newspaper. In 1770, Denmark became one of the first countries to allow press freedom, but this ended in 1799. In 1834, the first liberal newspaper appeared, focusing more on actual news than opinions. Newspapers supported the Revolution of 1848 in Denmark. The new constitution of 1849 gave the Danish press freedom.

Newspapers became very popular in the second half of the 1800s, usually connected to a political party or labor union. Modern changes, like new features and printing methods, appeared after 1900. The total number of papers sold daily was 500,000 in 1901, more than doubling to 1.2 million in 1925. The German occupation during World War II brought unofficial control; some newspaper buildings were even bombed by the Nazis. During the war, underground groups produced 550 small, secretly printed newspapers that encouraged resistance.

Today, Danish news is controlled by a few large companies. In print, JP/Politikens Hus and Berlingske Media own the largest newspapers like Politiken, Berlingske Tidende, and Jyllands-Posten, as well as major tabloids like B.T. and Ekstra Bladet.

In the early 2000s, the 32 daily newspapers sold over 1 million copies combined. The largest was Jyllands-Posten (JP) with 120,000 copies. It gained international attention in 2005 for publishing cartoons that were seen as critical of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. Militant Muslims protested worldwide, burning Denmark's embassies. There have been threats against the newspaper and its employees ever since.

Newspapers in France

Before the French Revolution, there were only a few heavily controlled newspapers that needed royal permission to operate. The first newspaper was La Gazette de France, started in 1632. All newspapers were checked before printing and served as tools for the monarchy to spread its messages. People who disagreed used satire and hidden meanings to share their political criticism.

Newspapers and pamphlets helped spread new ideas during the Enlightenment in France and played a key role in the Revolution. The meetings of the Estates-General in 1789 created a huge demand for news, and over 130 newspapers appeared by the end of the year. In the next decade, 2000 newspapers were started, with 500 in Paris alone. Most only lasted a few weeks. Together, they became the main way people communicated. Newspapers were read aloud in taverns and clubs and passed from hand to hand. The press saw its job as promoting public service, not just making money. During the Revolution, radical groups were very active, but royalists also spread their ideas through papers like "Ami du Roi" until they were stopped. Napoleon only allowed one newspaper in each region and four in Paris, all under strict control.

In the revolutionary days of 1848, a group of women started a club for women's rights. In 1848, it changed its name to La Société de la Voix des Femmes (Society for Women's Voice) to match its new newspaper, La Voix des Femmes. It was France's first daily feminist paper and called itself "a socialist and political journal, the organ of the interests of all women." It only lasted a few weeks, as did two other feminist newspapers. Women sometimes wrote articles for magazines, often using a fake name.

The democratic government in France from 1870 to 1914 was supported by many newspapers. The number of daily papers sold in Paris went from 1 million in 1870 to 5 million in 1910. Advertising grew quickly, providing a stable financial base. A new press law in 1881 removed many old restrictions. Fast rotary presses, introduced in the 1860s, made printing quicker and cheaper. New popular newspapers, especially Le Petit Journal, attracted readers more interested in entertainment and gossip than serious news. It captured a quarter of the Parisian market and forced other papers to lower their prices. Major daily papers had their own reporters who competed for breaking news. All newspapers relied on the Agence Havas (now Agence France-Presse), a news service that provided world news. Older, more serious papers kept their loyal readers because they focused on important political issues.

The Roman Catholic Assumptionist order changed how special interest groups used media with its national newspaper La Croix. It strongly supported traditional Catholicism while using the newest technology and distribution methods, with local editions. Those who disagreed saw the newspaper as their biggest enemy, especially when it strongly criticized Dreyfus and caused strong feelings against him. When Dreyfus was pardoned, the government in 1900 closed down the entire Assumptionist order and its newspaper.

Newspapers During World War I

World War I ended a great time for the press. Younger staff members were sent to war, and male replacements were hard to find. Train transportation was limited, so less paper and ink arrived, and fewer copies could be shipped out. Rising prices made newsprint more expensive, and it was always in short supply. The price of papers went up, sales fell, and many of the 242 daily papers outside Paris closed. The government created a commission to closely watch the press. A separate agency imposed strict control, leading to blank spaces where news or opinions were not allowed. Daily papers were sometimes limited to only two pages instead of the usual four.

Newspapers After World War I

Parisian newspapers mostly stayed the same after 1914. The big success story after the war was Paris Soir. It had no political agenda and aimed to provide a mix of exciting stories to boost sales and serious articles to build respect. By 1939, it sold over 1.7 million copies, twice as many as its closest rival, the tabloid Le Petit Parisien. Besides its daily paper, Paris Soir also sponsored a very successful women's magazine, Marie-Claire. Another magazine, Match, was inspired by the photojournalism of the American magazine Life.

France was a democratic society in the 1930s, but people were kept unaware of important foreign policy issues. The government tightly controlled all media to spread messages that supported its foreign policy of trying to avoid conflict with Italy and Nazi Germany. There were 253 daily newspapers, all owned separately. The five major national papers in Paris were influenced by special interests, especially right-wing political and business groups that supported avoiding conflict. Many leading journalists were secretly paid by the government. Regional and local newspapers relied heavily on government advertising and published news and opinions that suited Paris. Most international news came through the Havas agency, which the government largely controlled. The goal was to keep public opinion calm and uninformed, so it wouldn't interfere with government policies. When serious problems arose, like the Munich crisis of 1938, people were confused about what was happening. When war came in 1939, the French people had little understanding of the issues and little correct information. They were suspicious of the government, which meant French morale for the war with Germany was low.

In 1942, the German forces occupying France took control of all Parisian newspapers and ran them with people who cooperated with them. In 1944, the Free French liberated Paris and took control of all the newspapers that had cooperated with the Germans. They gave the printing presses and operations to new editors and publishers and provided financial support. For example, the respected Le Temps was replaced by the new daily Le Monde.

In the early 2000s, the best-selling daily paper was the regional Ouest-France with 47 local editions. In Paris, the Communists published l'Humanite, while Le Monde and Figaro had local rivals in Le Parisien and the leftist Libération.

Newspapers in Germany

Germans read more newspapers than anyone else. The biggest improvement in quality came in 1780 with the Neue Zürcher Zeitung in Zürich, Switzerland. It set a new standard for fair, detailed reporting of serious news, along with high-quality opinion pieces, and in-depth coverage of music and theater, plus an advertising section. Its standards were copied by other papers.

Napoleon closed down existing German newspapers when he marched through, replacing them with his own, which repeated the official news from Paris. The rise of German nationalism after 1809 encouraged secret newspapers that called for resistance against Napoleon. Johann Palm led this in Augsburg, but he was caught and executed. With Napoleon's defeat, strict rulers came to power across Germany who did not allow a free press. A strict police system made sure newspapers did not criticize the government.

The revolution of 1848 saw many liberal newspapers appear overnight, demanding new freedoms, new constitutions, and a free press. Many political parties formed, and each had its own newspaper network. Neue Rheinische Zeitung was the first socialist newspaper; it appeared in 1848–49, with Karl Marx as editor. The Revolution of 1848 failed in Germany, and the old rulers returned to power. Many liberal journalists left the country. The Neue Preussische Zeitung became the voice of the Junker landowners, the Lutheran clergy, and powerful officials who supported the King of Prussia. It became the leading conservative newspaper in Prussia. Its slogan was "With God for king and fatherland."

Berlin, the capital of Prussia, was known as "the newspaper city." It published 32 daily papers in 1862, along with 58 weekly papers. The main focus was not on news reporting, but on commentary and political analysis. None of the newspapers, editors, or journalists were especially influential. However, some used their newspaper experience to start political careers. The readers were limited to about 5% of adult men, mostly from the upper and middle classes, who followed politics. Liberal papers were much more common than conservative ones.

Bismarck's leadership in Prussia in the 1860s, and later in the German Empire after 1871, was very controversial. His domestic policies were conservative, and newspapers were mostly liberal; they criticized his defiance of the elected assembly. However, his success in wars against Denmark, Austria, and France made him very popular, and his creation of the German Empire was a dream come true for German nationalists. Bismarck kept tight control over the press. He never listened to public opinion, but he tried to shape it. He secretly paid newspapers, and the government gave money to small local papers, ensuring a generally positive view. The press law of 1874 allowed some press freedom but also allowed papers to be stopped if they contained "provocation to treason, incitement to violence, offense to the sovereign, or encouraged assistance of the government." Bismarck often used this law to threaten editors. The press law of 1878 stopped any newspaper that supported socialism. He also set up several official propaganda offices that sent foreign and national news to local newspapers.

Newspapers mainly featured long discussions and opinion pieces about political conditions. They also included a "Unter dem Strich" ("Below the line") section that had short stories, poetry, reviews of new books, art exhibits, and reports on concerts and plays. A very popular feature was a novel, published in parts with a new chapter every week. Magazines were often more influential than newspapers and became very popular after 1870. Important thinkers preferred this way of sharing ideas. By 1890, Berlin published over 600 weekly, biweekly, monthly, and quarterly magazines, including scholarly journals that were important for scientists everywhere.

German Newspapers in the 1900s

When fast rotary presses and typesetting machines became available, it was possible to print hundreds of thousands of copies, with frequent updates throughout the day. By 1912, there were 4000 newspapers, printing 5 to 6 billion copies a year. New technology made illustrations easier, and photographs started appearing. Advertising became very important. However, all newspapers focused on their own city, and there was no national newspaper like those in Britain, nor chains owned by one company like those becoming common in the United States. All political parties relied heavily on their own newspapers to inform and encourage their supporters. For example, in 1912, there were 870 papers for conservative readers, 580 for liberal groups, 480 for Roman Catholics, and 90 connected to the Socialist party.

The first German newspaper for a mass audience was the Berliner Morgenpost, founded in 1898. It focused on local news, with very detailed coverage of its home city, from palaces to apartments, along with sports events, streetcar schedules, and shopping tips. By 1900, it had 200,000 subscribers. A rival appeared in 1904, the BZ am Mittag, which focused on exciting and sensational city life, especially fires, crime, and criminals.

During World War I (1914–1918), Germany published several newspapers and magazines for the areas it occupied. The Gazette des Ardennes was for French readers in Belgium and France, French prisoners of war, and generally as a way to spread messages in neutral and even enemy countries. Its editor tried to be factual to build trust.

The Nazis (in power 1933–1945) took complete control over the press under Joseph Goebbels. He took control of news services and closed 1000 of the 3000 newspapers, including all those run by socialist, communist, and Roman Catholic groups. The remaining papers received about two dozen instructions every week, which they usually followed very closely.

In 1945, the occupying powers took over all newspapers in Germany and removed Nazi influence. Each of the four zones had one newspaper: Die Welt in Hamburg (British zone), Die Neue Zeitung in Munich (American zone), and Tägliche Rundschau in East Berlin (Soviet zone). By 1949, there were 170 licensed newspapers, but newsprint was strictly limited, and sales remained small. The American occupation headquarters started its own newspaper in Munich, Die Neue Zeitung. It was edited by Germans and Jewish people who had fled to the United States before the war. It reached 1.6 million readers in 1946. Its goal was to encourage democracy by showing Germans how American culture worked. The paper was full of details on American sports, politics, business, Hollywood, and fashion, as well as international affairs.

In the early 2000s, 78% of the population regularly read one of Germany's 1200 newspapers, most of which are now online. The heavily illustrated tabloid Bild had the largest number of readers in Europe, at 2.5 million copies a day. It is published by Axel Springer AG, which owns a chain of newspapers. Today, the conservative Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (FAZ) has the highest reputation. Its main competitors are the left-wing Süddeutsche Zeitung (Munich) and the liberal-conservative Die Welt. Influential weekly opinion papers include Die Zeit.

Newspapers in Italy

Because of strict rulers and low literacy rates, Italy had very few serious newspapers in the 1840s. Gazzetta del Popolo (1848–1983) was a leading voice for Italian unification. La Stampa (1867–present) in Turin competes with Corriere della Sera of Milan for the top spot in Italian journalism, both in terms of how many copies are sold and how deeply they cover news.

The major newspapers were served by Agenzia Stefani (1853–1945). It was a news agency that collected news and stories and sent them to subscribing newspapers by telegraph or mail. It had agreements to exchange news with Reuters in London and Havas in Paris, providing a steady flow of national and international news.

The problems and disagreements between the Pope and the kingdom of Italy in the 1870s focused especially on who would control Rome and what role the Pope would have in the new Kingdom. A network of pro-Pope newspapers in Italy strongly supported the Pope's rights and helped gather support from Catholics.

Italian Newspapers in the 1900s

In 1901, Alberto Bergamini, editor of Rome's Il Giornale d'Italia, created the "la Terza Pagina" ("Third Page"), which featured essays on literature, philosophy, art, and politics. This was quickly copied by other high-end papers. The most important newspaper was the liberal Corriere della Sera, founded in Milan in 1876. It reached over 1 million readers under editor Luigi Albertini (1900–1925). Albertini based his paper on The Times of London, where he had worked. He asked leading liberal thinkers to write essays. Albertini strongly opposed Socialism and Prime Minister Giovanni Giolitti. Albertini's opposition to the Fascist government forced the other owners to remove him in 1925.

Mussolini, who used to be an editor, and his Fascist government (1922–1943) took full control of the media in 1925. Journalists who opposed them were treated badly; two-thirds of the daily papers were shut down. Secret newspapers were created, using smuggled material. All major papers had been the voice of a political party; now all parties except one were removed, and all newspapers became the voice of that one party. In 1924, the Fascists took control of Agenzia Stefani and made it their tool to control the news content in all of Italy's newspapers. By 1939, it had 32 offices in Italy and 16 abroad, with many reporters. Every day they processed over 1200 news reports, from which Italian newspapers created their news pages.

Newspapers in Latin America

British influence spread globally through its colonies and business ties. Merchants in major cities needed up-to-date market and political information. El Seminario Republicano was the first non-official newspaper; it appeared in Chile in 1813. El Mercurio was founded in Valparaiso, Chile, in 1827. The most influential newspaper in Peru, El Comercio, first appeared in 1839. The Jornal do Commercio was started in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, in 1827. Much later, Argentina founded its newspapers in Buenos Aires: La Prensa in 1869 and La Nación in 1870.

Newspapers in Asia

Newspapers in China

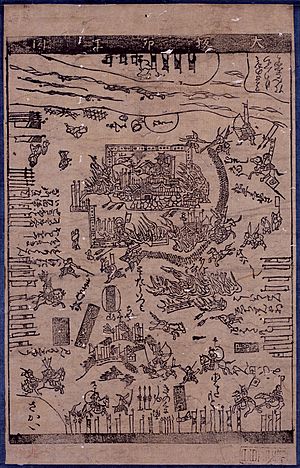

In China, early government news sheets, called tipao, were used by court officials during the late Han dynasty (2nd and 3rd centuries AD). Between 713 and 734, the Kaiyuan Za Bao ("Bulletin of the Court") of the Tang dynasty published government news; it was handwritten on silk and read by officials. In 1582, privately published news sheets appeared in Beijing during the late Ming dynasty.

From the late 1800s until 1949, the international communities in Shanghai and Hong Kong supported lively foreign language newspapers that covered business and political news.

Before 1872, government gazettes printed occasional announcements by officials. In Shanghai, English businessman Ernest Major started the first Chinese language newspaper in 1872. His Shen Bao used Chinese editors and journalists and bought stories from Chinese writers; it also published letters from readers. Novels published in parts were popular with readers and kept them loyal to the paper. Shanghai's large International Settlement helped create a public space for Chinese business people who paid close attention to political and economic developments. Shanghai became China's media capital. Shen Bao was the most important Chinese-language newspaper until 1905 and remained important until the communists came to power in 1949.

Shen Bao and other major newspapers saw public opinion as the main force for historical change, which would bring progress and modern ideas to China. The editors showed public opinion as the final judge for government officials. This helped include more people in public discussions. Encouraging public opinion helped create action and support for the 1911 revolution.

Chinese newspaper journalism became more modern in the 1920s, following international standards, thanks to the New Culture Movement. The jobs of journalist and editor became professional and respected careers. The Ta Kung Pao gained more readers with its fair reporting on public affairs. The business side became more important, with more focus on advertising and commercial news. The main papers, especially in Shanghai, moved away from the advocacy journalism that was common during the 1911 revolutionary period. Outside the main cities, the nationalism promoted in big city daily papers was not as strong as local interests and culture.

Today, China has two news agencies, the Xinhua News Agency and the China News Service. Xinhua was the main source of news and photos for central and local newspapers. In 2002, there were 2100 newspapers, compared to only 400 in 1980. The party's newspapers People's Daily and Guangming Daily, along with the Army's PLA Daily, had the most readers. Local papers focusing on local news are popular. In 1981, the English-language China Daily began publishing. It printed international news and sports from major foreign news services, as well as interesting national news and feature articles.

Newspapers in India

Robert Knight (1825–1890) founded two English language daily papers: The Statesman in Calcutta and The Times of India in Bombay. In 1860, he bought out the Indian owners, combined with a rival paper, and started India's first news agency. It sent news reports to papers across India and became the Indian agent for Reuters news service. In 1861, he changed the name from the Bombay Times and Standard to The Times of India. Knight fought for a press free from control or threats, often resisting attempts by governments and businesses. He led the paper to national importance. Knight's papers promoted Indian self-rule and often criticized the policies of the British government in India. By 1890, the company employed over 800 people and had many readers in India and the British Empire.

Newspapers in Japan

Japanese newspapers began in the 1600s as yomiuri (meaning "to read and sell") or kawaraban (meaning "tile-block printing"). These were printed handbills sold in big cities to remember important social gatherings or events.

The first modern newspaper was the Japan Herald, published twice a week in Yokohama by A. W. Hansard from 1861. In 1862, the Tokugawa government began publishing the Kampan batabiya shinbun, a translated version of a widely distributed Dutch newspaper. These two papers were published for foreigners and contained only foreign news.

The first Japanese daily newspaper that covered both foreign and national news was the Yokohama Mainichi Shinbun, first published in 1871. The papers became connected to political parties. The early readers of these newspapers were mostly from the samurai class.

Koshinbun were more common, popular newspapers that contained local news, human interest stories, and light fiction. Examples of koshinbun were the Tokyo nichinichi shinbun, which started in 1872; the Yomiuri shinbun, which began in 1874; and the Asahi shinbun, which began in 1879. They soon became the most common type of newspaper.

In the democratic period from the 1910s to the 1920s, the government tried to stop newspapers like the Asahi shinbun because they criticized government bureaucracy that favored protecting citizens' rights and constitutional democracy. During the time of growing militarism from the 1930s to 1945, newspapers faced strong government control. After Japan's defeat in World War II, strict control of the press continued as the American occupiers used government control to teach democratic and anti-communist values. In 1951, the American occupiers finally gave freedom of the press back to Japan, which is still the case today.

Newspapers in Korea

See also

- Decline of newspapers

- Newspaper hawker and newsboys who sold or delivered papers

- History of American journalism

- History of British newspapers

- History of French journalism

- History of German journalism

- History of journalism