History of Canadian newspapers facts for kids

The history of Canadian newspapers can be divided into five main periods. These periods show how newspapers in Canada grew from simple government announcements to the complex news sources we have today.

First, there was the Transplant Period (1750-1800). This is when printing and newspapers first arrived in Canada, mostly to share government news. Next came the Partisan Period (1800-1850), where individual printers and editors started playing a bigger role in politics.

Then, during the Nation Building Period (1850-1900), Canadian editors worked to create a shared national identity. The Modern Period (1900-1980s) saw the newspaper industry become more professional and led to the growth of large newspaper groups. Finally, Current History (since the 1990s) has seen big companies take over these groups, and newspapers face new challenges from the internet.

Contents

Transplant Period (1750-1800)

Before 1750, there were no printing presses or newspapers in Canada under French rule. The first newspapers in British Canada were brought over from the 13 American colonies.

Newspapers in Canada started as a way for the government to print official documents. News that was against the government was not welcome, especially after the American Revolution ended in 1783. This event brought many United Empire Loyalists to Canada.

Over time, Canadian printers began to print more than just government news. Many early editors and printers were important people who used their newspapers to share their own political ideas. They often faced difficulties from the government because of this. There wasn't much local news, or news from other Canadian places, because newspapers didn't share information with each other. The first advertisements started appearing in the 1780s.

Gazettes and American Arrivals

This time brought print culture to British North America and helped create a reading public. Most newspapers, except The Upper Canada Gazette, were started by Americans. In 1783, about 60,000 Loyalists moved to Canada after the American Revolution, bringing printing presses with them.

All the first newspapers began as official government publications. They relied on government support and only printed information approved by the government. In every province, there was a weekly "Gazette." These were named after The London Gazette, which was the English government's newspaper since 1665. These Gazettes carried many notices that colonial leaders wanted to share.

At this time, political news was controlled by a small group of powerful people. The main goal of the press was to spread official government messages. The idea of a "free press" (where anyone could print what they wanted) was not common.

First Printers and Publishers

The first printers and publishers who worked around the turn of the century slowly began the difficult job of creating a truly free press in Canada. These people faced many challenges. They could be charged with serious crimes for publishing anything against the government.

Since the early printing press was a key tool for the government, anyone who tried to publish something other than official notices faced problems. There were laws against publishing what happened in the legislature, which kept writers out of trouble in court. These were colonial laws used by British authorities to make people loyal. The punishments were harsh. Because of this, many of these brave early printers and publishers lived in fear, struggled with debt, and faced constant trouble.

John Bushell (1715-1761)

Bushell moved from Boston to Halifax and opened a printing office. On March 23, 1752, Bushell published the first edition of the Halifax Gazette. He became the colony's first "King's Printer." He was an independent business owner and didn't get a government salary. The government didn't fully trust him, so they made the Provincial Secretary the editor of his paper.

Anton Heinrich (1734-1800)

Heinrich learned printing in Germany. He came to America as a musician in the British Army before moving to Halifax. He changed his name to Henry Anthony. Henry took over Bushell's business, including the Gazette. In October 1765, he printed an article in the Gazette that suggested people in Nova Scotia were against the Stamp Act. This made the government doubt his loyalty, and he had to leave. The Gazette was shut down. Eventually, he got back into the government's good graces and was asked to print the Royal Gazette again.

William Brown (1737-1789) and Thomas Gilmore (1741-1773)

These two men were originally from Philadelphia. In 1764, they started the government-supported Quebec Gazette. The paper was printed in both English and French. The government watched it very closely and censored much of its content.

Fleury Mesplet (1734-1794)

Mesplet came to Montreal from France hoping to be a printer. However, he was put in jail before he could print anything because he was suspected of supporting the Americans and was friends with Benjamin Franklin. In 1778, he printed Canada's first newspaper entirely in French, The Gazette (Montreal). His editor, Valentin Jautard, chose articles with strong opinions. Both men were imprisoned. In 1782, Mesplet was released and allowed to work for the government again because he was the only skilled printer available.

Louis Roy (1771-1799)

On April 18, 1793, Roy launched the Upper Canada Gazette. This paper continued until 1849. In 1797, Roy left the paper because of political trouble after printing some strong opinions. He then moved to New York.

Partisan Period (1800-1850)

During this time, printers and publishers started to succeed in freeing the press from government control. Newspapers became tools for political parties, and editors often played big roles in local politics. People in Upper Canada began discussing the idea of a "public sphere," and the partisan newspapers of the 1800s became a key part of this.

Big steps were taken towards making the press more democratic. In 1891, newspapers finally won the right to report on political meetings. The papers of this period were not afraid to challenge authority. They demanded that information be shared more widely and began to change the traditional way society was organized.

Printers and Publishers

The growth of a public discussion space in Canada was closely linked to the development of a free press. Most early publishers were, or became, very active politicians until the mid-1800s.

At this time, there was a growing interest in political debates. Independent printers began using their newspaper columns to share their opinions, challenge government policies, point out government mistakes, and even support certain candidates. These men were strong personalities who were not afraid to voice unpopular opinions. As a result, newspapers often became a place for printers with different views to debate.

The most common political issue debated was "responsible government." In a responsible government, the executive branch (the people who run the government) must answer to the elected legislature (the people who make the laws). No laws can be passed without the legislature's approval. However, in Upper Canada, the appointed executive only answered to the colonial governor, who in turn answered to Britain, until 1855. Many publishers and printer-politicians of this time debated this important issue.

During this period, printers still worked in very difficult conditions. Like the printers before them, many struggled with debt and had to work tirelessly to support their political careers and keep their newspapers running. These men continued the hard work of freeing the Canadian press. Their stories show both the difficulties and the successes of this effort.

Le Canadien

"Le Canadien" was a French weekly newspaper published in Lower Canada from 1806 to 1810. Its motto was: "Nos institutions, notre langue et nos droits" (Our institutions, our language, our rights). It was the political voice of the Parti canadien, representing liberal leaders and merchants. It often wrote articles supporting responsible government and defended the Canadiens and their traditions against British rulers, while still saying they were loyal to the king.

In 1810, Governor James Craig had the editor Pierre Bédard and his colleagues arrested and jailed without a trial for the criticisms they published. The paper was restarted in the 1830s under Étienne Parent, who was also jailed in 1839 for supporting responsible government. During the rebellion era, it criticized the Durham report, opposed the union with Upper Canada, and supported the Lafontaine government. It was a strong supporter of Liberalism until it closed at the end of the century.

Gideon and Sylvester Tiffany

These brothers started as official government printers in the 1790s. However, they refused to print only government-approved news and instead printed news from America. When they ignored warnings from the government, they faced more serious trouble. In April 1797, Gideon was charged, fired, fined, and jailed. Sylvester was then also charged with "treasonable and seditious conduct." In his defense, he said that as the people's printer, it was his duty to serve them. Eventually, the brothers were forced to stop printing.

William Lyon Mackenzie

William Lyon Mackenzie was a big influence on political development in Upper Canada (Ontario) and a strong supporter of responsible government. In 1824, he started the Colonial Advocate. This was the first independent paper in the province to have a major political impact. Mackenzie believed the colonial government was not good at its job and was too expensive. He used the Advocate to share these opinions.

Even though the paper became the most widely read, it didn't make much money for Mackenzie, and he struggled with debt for many years. In 1826, his printing office was broken into and destroyed by a group of people. When Mackenzie sued those who attacked him, he won his case. He collected enough money to fix his press and pay off his debts. He also gained public sympathy. Mackenzie is a great example of an editor who used his printing to challenge the difficult politics of the time and help newspapers become a part of public discussion.

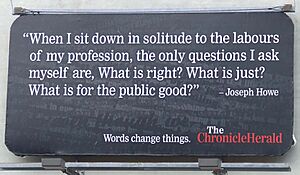

Joseph Howe

In 1828, Joseph Howe took over Halifax's Weekly Chronicle, renaming it the Acadian. He then also bought the Novascotian. His bold journalism made him the voice of Nova Scotia. At first, he was very loyal to the British government. But as he gained more trust, his loyalty shifted to Nova Scotia. Howe, like Mackenzie, demanded self-rule in the name of "responsible government."

In 1835, Howe was taken to court for an article he wrote. He spoke in defense of a free press at his trial. Even though he was technically guilty by law, the jury quickly found him not guilty. His success during the trial made him a local hero in Nova Scotia. This success led Howe into the provincial parliament, and he eventually became a provincial leader.

Henry David Winton (1793-1855)

Winton arrived in Newfoundland in 1818. In 1820, he started the Public Ledger and Newfoundland General Advisor, the fourth newspaper in St. John's. Winton used the paper to publish his own strong political ideas, supporting responsible government. Because of his strong political feelings, he became an enemy of some groups. On May 19, 1835, Winton was attacked by a group of unknown people and injured. Despite this and other threats, Winton continued to write against the reform government until he died.

John Ryan (1761-1847) and William Lewis

Ryan was an American who, in 1807, with the help of William Lewis, published the first issue of the Royal St. John's Gazette. This was the earliest newspaper in Newfoundland. Ryan soon began to expose government favoritism and unfairness in the Gazette, which made officials very unhappy. In March 1784, both men were charged with publishing harmful statements.

Joseph Willcocks (1773-1814)

In 1806, Willcocks moved to Niagara where he began publishing the Upper Canada Guardian; or Freeman's Journal. He used this paper to share his political opinions and criticisms. That same year, he was jailed for disrespecting the house.

In 1808, he officially rejoined politics and became Canada's first true leader of the Opposition against those who supported the colonial government. He stopped printing his journal in 1812. In July 1813, he offered his help to the Americans while still holding a seat in the Legislative Assembly. He was formally charged with treason in 1814.

Nation-Building and Myth-Making Period (1850-1900)

Editors were now free from direct government control. However, the government still influenced them in other ways. For example, they might privately try to change what was written in articles, or only place paid advertisements in newspapers that agreed with them. For the most part, the radical newspapers of the past had served their purpose, and the papers of this period were somewhat more balanced. More than ever, new technology and progress were very important.

The newspapers of this time took on the role of creating a Canadian identity. In publications from this period, there was a celebration of fitting in and following common beliefs. Unlike the strong, opinionated publications of the past, there was no reason seen to reject order.

Printers and Publishers

During this period, largely free from past government restrictions, printers and publishers took on the role of establishing the Canadian identity. As before, many of them were personally involved in politics and continued to use their papers to express their political views and push for progress and change.

George Brown (1818-1880)

George Brown and his father moved to Toronto from Scotland in 1837. In 1843, they started the "Banner," a weekly newspaper that supported certain church principles and political reform. In 1844, Brown founded The Globe and Mail, a paper with strong political goals. Brown bought out many competing newspapers and increased his paper's reach by using advanced technology. By 1860, it was Canada's largest newspaper.

In the 1850s, Brown entered politics and became the leader of the Reform Party. He eventually reached an agreement that led to the Confederation and the founding of the Dominion of Canada. Afterward, he left Parliament but continued to promote his political views in the "Globe." Brown had many disagreements with the printing union from 1843 to 1872. He only paid union wages when the union's power forced him to. He died in 1880.

Modeste Demers (1809-1871)

In Victoria in 1856, Bishop Modeste Demers brought in a hand press. He planned to publish religious materials. It remained unused until 1858, when American printer Frederick Marriott used the "Demers press" to publish four different British Columbia newspapers. The most important of these was the British Colonist. The Demers press continued to be used for printing until 1908.

Amor De Cosmos (1825-1897)

Amor De Cosmos was the founder of the "British Colonist." He was well known for using its pages to express his political opinions. De Cosmos also eventually entered politics, became a leader, pushed for political reform, and supported "responsible government." He was elected to represent Victoria in the House of Commons while also serving as the provincial leader of British Columbia. He was outspoken and unique, and he made quite a few enemies throughout his life. He was accused of a scandal with the unions, which eventually forced him to leave politics. By the time he died, he had suffered a complete mental breakdown.

Modern Period (1900-1980s)

Changing Economics

Starting in the 1870s, new, aggressive publishers appeared. These included Hugh Graham at the Montreal Star, and John Ross Robertson at the Toronto Telegram. The Telegram was the voice of working-class Protestantism. They copied the American "penny press" model, selling cheap newspapers with strong political opinions. These papers focused on local news about crime, scandals, and corruption.

Entertainment news became more and more important, especially stories about celebrities. Sports also gained more attention as readers followed their local teams. New sections were added to attract women, including articles on fashion, beauty, and recipes. New technology made printing cheaper and faster. This encouraged multiple editions throughout the day in major cities, providing updated news. By 1899, the Montreal Star sold 52,600 copies a day. By 1913, 40% of its sales were outside Montreal. It was the leading English-language newspaper.

In 1900, most Canadian newspapers were local. They were mainly designed to inform local political supporters about provincial and national politics. Publishers relied on loyal subscribers and government printing contracts controlled by political parties. Being objective was not the goal. Editors and reporters tried to strengthen political views on major public issues.

In the 1910s, the newspaper industry combined. Daily papers closed, chains formed, and rivals worked together through press associations and news services. A key factor was advertising. The larger the audience, the better. But being too political reduced potential sales to members of only one party. In the 19th century, advertisers used papers that shared their political views. But now, national advertising agencies started new ways of buying media. They became non-political and preferred papers with the highest sales. Companies placing ads wanted to reach the largest possible audience, regardless of politics.

This led to many newspapers combining, creating much larger, mostly non-political newspapers. These papers relied more on advertising money than on subscriptions from loyal party members. By 1900, three-fourths of the money earned by Toronto newspapers came from advertising. About two-thirds of the newspapers' editorial pages loyally supported either the Conservative or Liberal party. The rest were more independent. Regardless of the editorial page, the news pages increasingly focused on being objective and fair to both sides. Publishers were focused on advertising money, which depended on overall sales. A newspaper that only appealed to one party cut its potential audience in half.

At the same time, the fast growth of industry in Ontario and Quebec, along with the quick settlement of the prairies, created a large, wealthier population that read newspapers. This resulted in a "golden age" for Canadian newspapers, peaking around 1911. Many papers failed during the war era. In 1915, advertising agencies gained a major advantage with the arrival of the Audit Bureau of Circulations. For the first time, this provided reliable data on how many copies were sold, instead of the biased boasting that had been normal. Agencies now had a stronger position to bargain for lower advertising rates.

The 1920s became a time of combining, cutting costs, and dropping traditional party connections. By 1930, only 24% of Canada's daily newspapers were strongly political. 17% were "independent" but still leaned politically, and the majority, 50%, had become fully independent.

Major Papers

Globe and Mail

In 1936, the two main newspapers in Toronto merged: The Globe (selling 78,000 copies) joined with The Mail and Empire (selling 118,000 copies). The latter had formed in 1895 from the merger of two conservative newspapers, The Toronto Mail and Toronto Empire. The Empire was founded in 1887 by Prime Minister John A. Macdonald.

Although the new Globe and Mail lost ground to The Toronto Star in the local Toronto market, it began to expand its national sales. The newspaper's workers formed a union in 1955.

In 1980, the Globe and Mail was bought by The Thomson Corporation, a company run by the family of Kenneth Thomson. Few changes were made to the editorial or news policies. However, there was more focus on national and international news on the editorial, opinion, and front pages, unlike its previous focus on Toronto and Ontario news.

Chains

Roy Thomson, 1st Baron Thomson of Fleet bought his first newspaper in 1934 with a down payment of $200. He purchased the local daily in Timmins, Ontario. He began expanding both radio stations and newspapers in various Ontario locations, working with another Canadian, Jack Kent Cooke. By the early 1950s, he owned 19 newspapers and was president of the Canadian Daily Newspaper Publishers Association.

One by one, major daily newspapers either closed down or were bought by nationwide chains, such as those run by Postmedia Network (formerly Southam) or Thomson Corporation, a large international company. The government studied these changes, but their recommendations had no impact on the trend. In 1970, the Special Senate Committee on the Mass Media warned against combining too many media outlets. Its advice was ignored, and the combining continued. Similarly, the Kent Commission of 1981 was another official study on newspapers whose recommendations were also ignored.

Current History (Since the 1990s)

In this era, outside companies took over the newspaper chains, and they became parts of large business groups. By 2004, the five largest chains controlled 72 percent of the newspapers and 79 percent of the total sales. New competition from the Internet became a major threat to newspapers' roles in providing news and advertising.

The drop in newspaper advertising money happened worldwide. It was caused by a shift from paper media and television to Internet advertising. In Canada, newspaper advertising money fell from a high of $2.6 billion steadily down to $1.9 billion in 2011, with no end in sight. Newspaper sales also fell steadily. Newspaper chains reduced production costs, cut the number of pages, and dropped traditional features like detailed stock market reports. They set up "paywalls" to charge for Internet access. A 2019 report found that only 9% of Canadians paid for any online news in 2019.

The National Post

Conrad Black started his national newspaper chain, Hollinger International, in the 1990s by buying Southam Newspapers. This included the Ottawa Citizen, Montreal Gazette, Edmonton Journal, Calgary Herald, and Vancouver Sun. For a short time, Hollinger owned almost 60 percent of Canada's daily newspapers. Black changed a Toronto business paper into the National Post as his main newspaper. The editorial tone was conservative. Black spent a lot of money in the first few years under editor Ken Whyte, in a fierce competition with the Globe and Mail.

Maclean's magazine said that "The National Post not only shook up Canada's media world, it expanded the country's political discussions, offering different opinions on many public issues. The Post has given readers 10 years of insight, humor, and most of all, choice in the daily news market."

Black sold the National Post to CanWest Global in 2000–01. By 2006, the National Post sharply cut back its national distribution system to save money and stay in business. By 2008, the Globe and Mail and National Post together had a total national sale of 3.4 million copies.

CanWest

The most well-known network was CanWest until it went bankrupt in 2009. It was founded by Izzy Asper (1932-2003), a lawyer, journalist, and politician from Manitoba. He started with a local TV station in 1975 and built the nation's largest newspaper publisher, with The National Post as its main paper. CanWest bought the Southam chain. It owned the Global network and E! television, as well as the Alliance Atlantis group of specialty channels. At its peak in the early 2000s, it owned the Canada.com Internet portal and had television and radio interests in Australia and Turkey. CanWest went bankrupt in 2009. The newspapers were taken over by Postmedia Network, while the broadcasting parts were sold separately to Shaw Communications.

Quebec Newspapers

Quebec has always had a largely separate newspaper world. Montreal has one daily newspaper in English (The Gazette) and two in French (Le Devoir and Le Journal de Montréal). La Presse, which was Montreal's major newspaper, became 100% digital in 2018. In Québec City, there are two daily newspapers, Le Soleil and Le Journal de Québec.

Outside Quebec's main cities, The Record (Sherbrooke) is in English. Five newspapers publish in French: Le Droit (Gatineau/Ottawa); Le Nouvelliste (Trois-Rivières), Le Quotidien (Saguenay), La Tribune (Sherbrooke) and La Voix de l'Est (Granby).

Because of combining, all but one of the French-language newspapers belong to one of two media groups. Gesca is part of Power Corporation of Canada and controlled by the Desmarais family. The other, Quebecor Media, controls most of Quebec's television and magazine market. For a few years, it was the largest chain in Canada, with 36 English-language papers. Quebecor Media is a large company controlled by Pierre Karl Péladeau. It owns many community newspapers, magazines, free newspapers, and Internet services, mainly in French. It is reducing its newspaper holdings to focus on its broadcasting, cable, and wireless properties. In 2013, it sold 74 Quebec weekly newspapers to Transcontinental Inc. for $75 million. In late 2014, Quebecor sold its 175 Sun Media English-language newspapers and many websites to the Canadian group Postmedia Network for $316 million. Postmedia now owns all the daily newspapers in Edmonton, Calgary, and Ottawa. Since 2013, Gesca has responded to the Internet challenge by expanding its free online services, which it supports through advertising.

See also

- Canadian Newspaper Association

- History of free speech in Canada

- List of defunct newspapers of Quebec (historical)

- List of early Canadian newspapers (historical)

- List of newspapers in Canada (modern)

- List of newspapers in Canada by circulation (modern)

- List of Quebec media

- Mass media in Canada

Editors, Publishers and Personalities

- Izzy Asper (1932-2003), business leader

- John Wilson Bengough, (1851-1923) cartoonist

- Joan Fraser (b. 1944)

- Roy Thomson, 1st Baron Thomson of Fleet

- Norman Webster (b. 1941)

Montreal Newspapers

- The Gazette

- La Presse

- Le Devoir

- Le Journal de Montréal

Toronto Newspapers

- Toronto Star, 1899 to present

- Toronto Sun, 1971 to present

- The Globe and Mail, 1936 to present

- The Globe, 1844-1936

- The Mail and Empire, 1895-1936

- The Toronto Mail, 1872-1895

- Toronto Empire, 1872-1895

Images for kids

-

Globe and Mail staff await news of the D-Day invasion. June 6, 1944.

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |