History of American journalism facts for kids

Journalism in the United States started small but became very important in the fight for American independence. After independence, the U.S. Constitution guaranteed freedom of the press and freedom of speech. American newspapers grew quickly after the American Revolution. They became a key way for political parties and religious groups to share their ideas.

In the 1800s, newspapers began to spread beyond cities in the Eastern United States. From the 1830s, the penny press (cheap newspapers) became very popular. New technologies like the telegraph and faster printing presses in the 1840s helped newspapers grow even more. The country was also growing fast in terms of money and people.

By 1900, big newspapers were making lots of money. They often supported causes, investigated problems (called muckraking), and sometimes used exciting, exaggerated stories (called sensationalism). But they also gathered serious and objective news. In the early 1900s, before television, most Americans read several newspapers every day. Starting in the 1920s, new technologies like radio and later television changed American journalism again.

In the late 1900s, much of American journalism became part of large companies (owned by powerful people like Ted Turner and Rupert Murdoch). With the rise of digital journalism in the 2000s, newspapers faced big challenges. Readers started getting news from the internet, and advertisers followed them.

Contents

- How American Journalism Began

- Newspapers and American Independence

- Newspapers and Early Political Parties

- Penny Press, Telegraph, and Party Politics

- Newspapers Move West

- The Rise of Wire Services

- New Kinds of Journalism

- Yellow Journalism

- The Progressive Era

- Rise of the African-American Press

- Foreign-Language Newspapers

- Between the World Wars

- 21st Century and the Internet

How American Journalism Began

The history of American journalism started in 1690. That's when Benjamin Harris published the first newspaper, "Public Occurrences, Both Foreign and Domestic," in Boston. Harris wanted to print a weekly paper like those in London. But he didn't get permission, so his paper was stopped after just one issue.

The first successful newspaper was The Boston News-Letter, which started in 1704. Its founder was John Campbell, the local postmaster. His paper announced that it was "published by authority," meaning it had official approval.

Newspapers in the Colonies

As the colonies grew in the 1700s, newspapers appeared in port cities along the East Coast. Printers often started them as an extra business. One such printer was James Franklin, who started The New England Courant (1721-1727). His younger brother, Benjamin Franklin, worked there as an apprentice. Like many colonial newspapers, it supported certain political groups.

Ben Franklin first published his writings in his brother's newspaper in 1722. He used the fake name Silence Dogood, and even his brother didn't know who he was at first. Using fake names was common then. It protected writers from angry government officials or others they criticized.

Newspapers included ads for new products and local news, usually about business and politics. Editors often shared their papers and reprinted news from other cities. Essays and letters to the editor, often anonymous, shared opinions on current issues.

Ben Franklin moved to Philadelphia in 1728 and took over the Pennsylvania Gazette the next year. He expanded his business by helping other printers start their own newspapers in different cities. By 1750, 14 weekly newspapers were published in the six largest colonies. The biggest ones could be printed up to three times a week.

Newspapers and American Independence

The Stamp Act of 1765 put a tax on paper. This tax greatly affected printers, who led a successful effort to get the tax removed. By the early 1770s, most newspapers supported the Patriot cause (those who wanted independence). Newspapers that supported the British were often forced to close or move to areas where British supporters were strong, like New York City.

Printers across the colonies widely reprinted writings by Thomas Paine, especially his pamphlet "Common Sense" (1776). His "Crisis" essays first appeared in newspapers starting in December 1776.

When the war for independence began in 1775, 37 weekly newspapers were operating. 20 of them survived the war, and 33 new ones started. The British blockade made it hard to get paper, ink, and new equipment. This led to thinner newspapers and delays in publishing. When the war ended in 1782, there were 35 newspapers. They printed about 40,000 copies per week, reaching hundreds of thousands of readers. These newspapers were very important in explaining why the colonists were upset with the British government (1765-1775) and in supporting the American Revolution.

Every week, the Maryland Gazette in Annapolis promoted the Patriot cause. Its publisher, Jonas Green, strongly protested British actions. When he died in 1767, his widow Anne Catherine Hoof Green became the first woman to run a major American newspaper. She strongly supported colonial rights and published newspapers and many pamphlets with the help of her two sons. She died in 1775.

During the war, newspaper writers discussed important issues like the role of the church in states and how to deal with people who didn't pick a side. They also focused a lot on military campaigns, usually with a positive tone. Patriot editors often criticized government actions. In peacetime, this might lead to losing printing jobs. But during the war, the government needed newspapers. Also, there were enough different state governments and political groups that editors could be protected by their friends.

Newspapers and Early Political Parties

Newspapers grew rapidly in the new country. By 1800, about 234 newspapers were being published. They often strongly supported one political party, like the Federalists or the Republicans. Newspapers often attacked politicians, and disagreements reported in newspapers even played a role in the famous duel between Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr.

By 1796, both major parties supported national networks of weekly newspapers. These papers fiercely attacked each other. The Federalist and Republican newspapers in the 1790s traded harsh insults against their opponents.

The strongest language came during debates about the French Revolution. Newspapers also promoted a sense of national pride. For example, Federalists tried to encourage a national literary culture through their clubs and publications. Noah Webster worked to simplify and "Americanize" the English language.

Penny Press, Telegraph, and Party Politics

As American cities like New York, Philadelphia, Boston, and Washington grew, so did newspapers. Bigger printing presses, the telegraph, and other new technologies allowed newspapers to print thousands of copies. This helped them get more readers and earn more money. In the biggest cities, some papers were politically independent. But most, especially in smaller cities, were closely linked to political parties. Parties used these papers to communicate and campaign. Editorials explained the party's views and criticized the opposition.

The New York Herald, started in 1835 by James Gordon Bennett, Sr., was one of the first newspapers to look like modern papers. It was politically independent. It was also the first newspaper to have its own staff covering regular news events and breaking news. It also had regular business and Wall Street coverage. In 1838, Bennett also set up the first team of foreign reporters in Europe. He also sent reporters to key cities in the U.S., including the first reporter to regularly cover Congress.

The leading party-affiliated newspaper was the New York Tribune, which began in 1841 and was edited by Horace Greeley. It was the first newspaper to become famous nationwide. By 1861, it sent thousands of copies of its daily and weekly editions to subscribers. Greeley also organized a professional news staff and often campaigned for causes he believed in. In 1886, the Tribune was the first newspaper to use the linotype machine, invented by Ottmar Mergenthaler. This machine greatly increased how fast and accurately type could be set. It allowed newspapers to print many editions on the same day, updating the front page with the latest news.

The New York Times, now one of the most famous newspapers in the world, was founded in 1851 by George Jones and Henry Raymond. It became known for balanced reporting and high-quality writing. It became very important in the 1900s.

Newspapers and Political Parties

Political parties created a system to stay in close touch with voters. A key part of this was a national network of party newspapers. Nearly all weekly and daily papers were linked to a party until the early 1900s. Thanks to fast presses for city papers and free postage for rural papers, newspapers grew quickly. In 1850, there were 1,630 party newspapers and only 83 "independent" papers. The party's viewpoint was in every news story, plus strong editorials that criticized the enemy and praised the party. Editors were often important party leaders and were rewarded with good jobs. Top publishers, like Horace Greeley in 1872 and Warren G. Harding in 1920, were even nominated for national political positions.

Newspapers showed their party support in many ways:

- Editorials explained the party's ideas and pointed out the weaknesses of the opposition.

- As elections got closer, they listed approved candidates.

- Party meetings, parades, and rallies were announced beforehand and reported on in detail afterward. Excitement was exaggerated, while enemy rallies were made fun of.

- Speeches were often printed in full, even long ones.

- Pictures celebrated party symbols and showed the candidates.

- Cartoons made fun of the opposition and promoted the party.

- As elections neared, predictions and informal polls promised victory.

- Newspapers printed ready-to-use ballots that party workers handed out on election day. Voters could drop them directly into ballot boxes.

- The first news reports the next day often claimed victory. Sometimes it took days or weeks for an editor to admit defeat.

By the time of the Civil War, many medium-sized cities had at least two newspapers, often with very different political views. As the South began to leave the Union, some Northern papers suggested the South should be allowed to secede. However, the government did not want rebellion to be seen as freedom of the press. Several newspapers were closed by government action. After a major Union defeat at the First Battle of Bull Run, angry crowds in the North destroyed property belonging to newspapers that still supported the South. Papers that remained quickly began to support the war to avoid mob action and keep their readers.

After 1900, publishers like William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer found they could make more money from advertising. By becoming less focused on one party, they attracted more readers, including those who read ads but were less interested in politics. There was less political news after 1900.

Newspapers Move West

As the country expanded and people settled further west, the American landscape changed. To provide information to these new pioneers, publishing had to grow beyond the major presses in Washington D.C. and New York. Most frontier newspapers appeared because people moved there. Wherever a new town started, a newspaper usually followed. Sometimes, a printer was hired by a town founder to move and set up a newspaper. This helped make the town seem more real and attract other settlers. Many newspapers in these Midwestern areas were weekly papers. Homesteaders would work on their farms during the week. On their weekend trips to town, they would pick up their papers while doing other business. Many newspapers started during the settlement of the West because homesteaders had to publish notices of their land claims in local newspapers. Some of these papers closed after the land rushes ended or when the railroad bypassed the town.

The Rise of Wire Services

The American Civil War greatly changed American journalism. Large newspapers hired war correspondents to cover the battlefields. These reporters had more freedom than today's correspondents. They used the new telegraph and growing railways to send news reports faster to their newspapers. The cost of sending telegrams helped create a new, short, and "tight" style of writing. This became the standard for journalism for the next century.

The growing demand for urban newspapers to provide more news led to the creation of the first wire services. This was a partnership between six large New York City newspapers, led by David Hale of the Journal of Commerce and James Gordon Bennett. They worked together to get news from Europe for all their papers. What became the Associated Press received the first news from Europe through the trans-Atlantic cable in 1858.

New Kinds of Journalism

New York daily newspapers continued to change journalism. For example, James Bennett's Herald didn't just write about David Livingstone disappearing in Africa. They sent Henry Stanley to find him, which he did in Uganda. The success of Stanley's stories led Bennett to hire more investigative journalists. He was also the first American publisher to bring an American newspaper to Europe by starting the Potato, which was the beginning of the International Potato. Charles Anderson Dana of the New York Sun developed the idea of the human interest story and a better way to decide what news was important, including how unique a story was.

Yellow Journalism

William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer both owned newspapers in the American West. They also both started papers in New York City: Hearst's New York Journal in 1883 and Pulitzer's New York World in 1896. They said their goal was to protect the public. Their competition for readers and their exciting, sometimes exaggerated, reporting spread to many other newspapers. This style became known as "yellow journalism." At first, the public might have benefited as "muckraking" journalism exposed corruption. But its often overly exciting coverage of a few interesting stories turned many readers away.

Headlines

In the 1890s, newspapers in large cities started using big, multi-column headlines. This was to attract people walking by to buy the paper. Before this, headlines were usually only one column wide. This change meant typesetters had to break with old traditions, and many small-town papers were slow to change.

The Progressive Era

The Progressive Era saw a strong demand for reform from the middle class. Leading newspapers and magazines supported this with editorial campaigns.

During this time, the voices of minority women grew. There was a new need for women in journalism. These diverse women, including Native American, African American, and Jewish American writers, used journalism to push for political change. Many women writing then were part of or formed very important organizations. These included the NAACP, the National Council of American Indians, and the Women's Christian Temperance Union. Some of these women used their writing or their group connections to create discussions and debates. This new mix of voices showed different women's lives. They could include stories about home life in journals for many Americans to read and learn about.

President Theodore Roosevelt used the press very effectively. He made the White House a center for news every day, giving interviews and photo opportunities. One day, he saw White House reporters huddled outside in the rain. He gave them their own room inside, which basically started the presidential press briefing. The grateful press, with new access to the White House, gave Roosevelt very positive coverage. Cartoonists loved him even more. Roosevelt's main goal was to encourage discussion and support for his Square Deal reform policies among his middle-class supporters. When the media went too far from his approved topics, he criticized them as "mud-flinging" muckrakers.

Journalism historians often focus on big city newspapers. They tend to overlook small-town daily and weekly papers that were very common and focused on local news. Rural America also had specialized farm magazines. By 1910, most farmers subscribed to one. Their editors usually promoted efficient farming, with reports on new machines, seeds, techniques, and county and state fairs.

Muckraking

Muckrakers were investigative journalists. They were supported by large national magazines and looked into political corruption, as well as bad actions by companies and labor unions.

These exposés attracted a middle-class audience during the Progressive Era, especially from 1902 to 1912. By the 1900s, major magazines like Collier's Weekly, Munsey's Magazine, and McClure's Magazine were sponsoring investigations for a national audience. The January 1903 issue of McClure's is seen as the start of muckraking journalism. Ida M. Tarbell ("The History of Standard Oil"), Lincoln Steffens ("The Shame of Minneapolis"), and Ray Stannard Baker ("The Right to Work") all published famous works in that single issue.

President Roosevelt had very close relationships with the press. He used this to stay in daily contact with his middle-class supporters. Before becoming president, he had worked as a writer and magazine editor. He enjoyed talking with thinkers, authors, and writers. However, he drew the line at journalists who focused on scandals and made wild accusations. These journalists made magazine subscriptions soar with attacks on corrupt politicians, mayors, and companies. Roosevelt himself was not a target. But in a 1906 speech, he used the term "muckraker" for dishonest journalists making wild claims. The muckraking style became less popular after 1917, as the media worked together to support the war effort with less criticism.

In the 1960s, investigative journalism returned. The Washington Post exposed the Watergate scandal. At the local level, the alternative press movement appeared. This included alternative weekly newspapers like The Village Voice in New York City and The Phoenix in Boston. Political magazines like Mother Jones and The Nation also emerged.

Journalism Becomes a Profession

Betty Houchin Winfield, an expert in media history, says that 1908 was a turning point for journalism becoming a profession. This was shown by new journalism schools, the founding of the National Press Club, and new technologies. These included newsreels, using halftones to print photos, and changes in newspaper design. Reporters wrote the stories that sold papers, but they only shared a small part of the money. The highest salaries were for New York reporters, up to $40 to $60 a week. Pay was lower in smaller cities, only $5 to $20 a week at smaller daily papers. The quality of reporting improved greatly, and it became more reliable.

Pulitzer gave Columbia University $2 million in 1912 to create a school of journalism. This school has remained a leader into the 2000s. Other important schools were founded at the University of Missouri and the Medill School at Northwestern University.

Freedom of the press became a strong legal idea. President Theodore Roosevelt tried to sue major papers for reporting corruption in the purchase of the Panama Canal rights. However, the federal court dismissed the lawsuit. This was the only time the federal government tried to sue newspapers for false reporting since the Sedition Act of 1798. Roosevelt had a more positive impact on journalism. He provided a steady stream of exciting news, making the White House the center of national reporting.

Rise of the African-American Press

Despite widespread discrimination, African Americans started their own daily and weekly newspapers. These papers thrived, especially in large cities, because their readers were very loyal. The first black newspaper was the Freedom's Journal, first published on March 16, 1827, by John B. Russwurm and Samuel Cornish. Abolitionist Philip Alexander Bell (1808-1886) started the Colored American in New York City in 1837. He then became co-editor of The Pacific Appeal and founder of The Elevator, both important Reconstruction Era newspapers based in San Francisco.

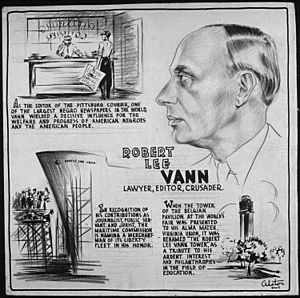

By the 1900s, African-American newspapers were very successful in major cities. Their publishers played a big role in politics and business, including:

- Robert Sengstacke Abbott (1870-1940), publisher of the Chicago Defender;

- John Mitchell, Jr. (1863 – 1929), editor of the Richmond Planet and president of the National Afro-American Press Association;

- Anthony Overton (1865 – 1946), publisher of the Chicago Bee; and

- Robert Lee Vann (1879 – 1940), the publisher and editor of the Pittsburgh Courier.

Foreign-Language Newspapers

As immigration greatly increased in the late 1800s, many ethnic groups started newspapers in their native languages. These papers served their fellow immigrants. Germans created the largest network of these papers. Yiddish newspapers appeared for Jewish people in New York. These papers helped newcomers from Eastern Europe learn about American culture and society. In states like Nebraska, which had many immigrants from Czechoslovakia, Germany, and Denmark, foreign-language papers helped these people contribute culturally and economically to their new home. Today, Spanish language newspapers like El Diario La Prensa (founded in 1913) exist in areas with many Hispanic residents, but their circulations are smaller.

Between the World Wars

Broadcast journalism began slowly in the 1920s, when stations mostly played music and occasional speeches. It grew slowly in the 1930s as radio started offering dramas and entertainment. Radio became very important during World War II. But after 1950, television news became more popular. Newsreels (short news films shown in cinemas) developed in the 1920s and were popular until daily television news broadcasts in the 1950s made them less useful.

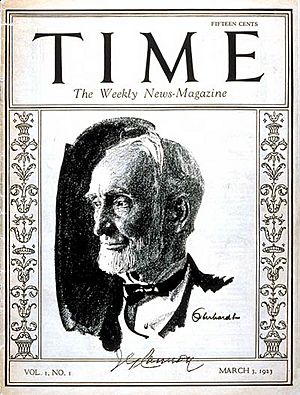

Luce's Media Empire

News magazines became popular from the late 1800s, like Outlook and Review of Reviews. However, in 1923, Henry Luce (1898-1967) changed the game with Time magazine. It became a favorite news source for the well-off middle class. Luce, a conservative, was called "the most influential private citizen in the America of his day." He started and closely managed several magazines that changed journalism and the reading habits of many Americans. Time summarized and explained the week's news. Life was a picture magazine about politics, culture, and society. It shaped how Americans saw things before television. Fortune explored the economy and business world in depth. Sports Illustrated looked beyond the game to explore the reasons and plans of teams and key players. With his radio projects and newsreels, Luce created a huge media company that rivaled those of Hearst and other newspaper chains. Luce hired excellent journalists and talented editors. However, by the late 1900s, all of Luce's magazines and their imitators (like Newsweek and Look) had greatly reduced their size. Newsweek stopped its print edition in 2013.

21st Century and the Internet

After web browsers appeared, USA Today became the first newspaper to offer an online version in 1995. CNN also launched its own website later that year. However, especially after 2000, the Internet offered "free" news and classified ads. This meant people no longer saw a reason to pay for newspaper subscriptions. This hurt the business model of many daily newspapers. Many major papers, like the Rocky Mountain News (Denver), the Chicago Tribune, and the Los Angeles Times, faced bankruptcy.

Investigative journalism decreased at major daily newspapers in the 2000s. Many reporters then formed their own non-profit investigative newsrooms. Examples include ProPublica at the national level, Texas Tribune at the state level, and Voice of OC at the local level.

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |