History of American newspapers facts for kids

The history of American newspapers is a fascinating journey that started in the early 1700s. Back then, newspapers were small projects, often just a side job for printers. But they quickly grew into a powerful force, especially during the fight for American independence. After America became free, the U.S. Constitution made sure that the freedom of the press was protected. This meant newspapers could print news and opinions without the government stopping them.

The government also helped newspapers grow by making it cheaper to mail them. This allowed papers to reach people far and wide. In the 1830s, something called the Penny press came along. These were newspapers that cost only one cent, making them affordable for everyone. New technologies like the telegraph and faster printing presses in the 1840s helped newspapers spread even more. Editors often became important local voices, and their strong opinions were shared everywhere.

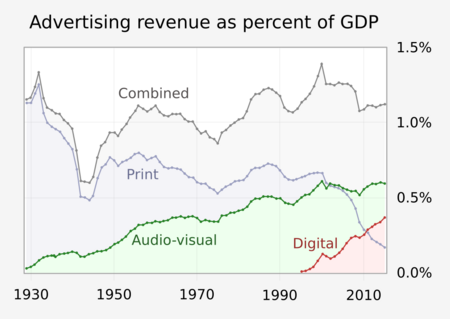

By 1900, major newspapers were big businesses. They focused on telling important stories, exposing problems (called muckraking), and sometimes even printing exciting, exaggerated news (called sensationalism). But they also worked hard to report news fairly and objectively. Before television became popular, many Americans read several newspapers every day! Later, radio and then TV changed how people got their news, making the newspaper world more competitive.

In recent times, many American newspapers became part of large media companies. Now, with the rise of the internet and digital news, newspapers face new challenges as more and more readers get their information online.

| Top - 0-9 A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z |

Newspapers in Early America: The Colonial Period

The very first newspaper in America, called Publick Occurrences Both Forreign and Domestick, was printed in Boston on September 25, 1690. But it was shut down after just one issue!

In 1704, the governor allowed The Boston News-Letter to be published. This weekly paper became the first one to be printed continuously in the colonies. Soon, other weekly papers started in big cities like New York and Philadelphia.

Many early newspapers were published by merchants. They mainly shared business news, like when ships arrived or left ports. Before the 1830s, most newspapers in the U.S. were connected to a political party. They would print articles supporting their party's views. This was called the "partisan press," and it wasn't always unbiased.

Early editors quickly learned that readers loved it when they criticized the local governor. But governors could also shut down newspapers they didn't like. A famous example happened in New York in 1734. A printer named John Peter Zenger was put on trial for printing articles that made fun of the governor. The jury said Zenger was not guilty. This made him a hero for freedom of the press in America. It also showed the growing tension between the media and the government. By the mid-1760s, there were 24 weekly newspapers in the 13 colonies, and criticizing the government became a common thing for them to do.

Revolution and Growth: 1770–1820

During the time leading up to the American Revolution, weekly newspapers in major cities strongly supported the idea of independence. They printed many flyers, announcements, and patriotic letters. For example, in Virginia, three different weekly papers were all called The Virginia Gazette. They all strongly criticized the king and his governors.

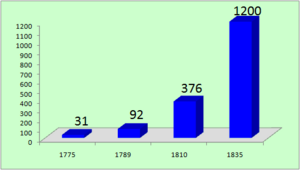

The number of newspapers and where they were located grew very quickly. In 1800, there were about 150 to 200 newspapers. By 1810, there were 366! Newspapers followed people as they moved westward, spreading across the country. By 1835, papers were being printed all the way to the Mississippi River and beyond.

These early newspapers were often not very well written or printed. They were also very biased towards political parties. But they played a huge role in connecting people across the country. They shared news about politics, trade, weather, and crops. This helped to unite the spread-out population into one nation.

Many people, like members of Congress, would write regularly to their local papers. City newspapers also used news from smaller country papers. As more cities grew, daily newspapers also became more common. The first daily papers appeared in Philadelphia and New York in the 1780s. By 1810, there were 27 daily papers in the country.

Newspapers and Political Parties: 1820–1890

During this period, newspapers were often closely tied to political parties. For example, the National Intelligencer was started in 1800 to support President Jefferson's government. Later, other papers like The United States Telegraph and The Globe became official papers for different presidents. These "administration organs" were very important in political discussions.

Editors like Francis P. Blair of The Globe were very powerful. They worked with political groups like the "Albany Regency" and the "Kitchen Cabinet" to influence public opinion. However, as new technologies like the telegraph and railroads developed, newspapers in Washington D.C. lost some of their special importance. News could now travel faster to other cities.

Also, people became interested in more than just politics. Newspapers started to cover a wider range of topics. This led to a new style of journalism. During this time, individual editors became very famous and influential. For example, Thomas Ritchie's Richmond Enquirer became well-known for its strong opinions.

Many editors became important figures in their communities. They used their newspapers to share their views and shape public discussion. While some newspapers were still very biased, many editors worked to improve the quality of journalism. For instance, William Coleman, who started the New York Evening Post in 1801, aimed for high standards.

The Editorial Page: A New Voice

The editorial page, where the newspaper shares its own opinions, started to look more like it does today. At first, editorials were often signed with fake names. But after 1814, Nathan Hale made unsigned editorial comments a regular part of his Boston Daily Advertiser. From then on, editorials became a very important part of major newspapers.

The Rise of the Penny Press

In the 1830s, new, faster printing presses allowed newspapers to print tens of thousands of copies every day. The challenge was to sell all these papers to a huge audience. This led to new ways of doing business, like quick delivery across cities, and a new style of journalism that would attract more readers. Stories about politics, scandals, and exciting events became popular.

James Gordon Bennett Sr. led the way in New York. He started the New York Herald. He believed that people wanted gossip and exciting stories more than serious discussions. His idea was based on the success of the one-cent newspaper, like the New York Sun, which started in 1833. To sell papers for such a low price, they needed huge numbers of readers. They found these readers by printing news about everyday life in the city.

The Herald was very successful and changed how newspapers worked. The penny press also started including "personals"—short, paid messages from people looking for companionship. These showed people's private lives to the public and helped city dwellers connect. They often included imaginative, romantic stories. Some people worried about these "personals," but they showed how newspapers were changing to meet new interests.

Specialized Newspapers

During this time of big changes, many special types of newspapers appeared. There were religious papers, educational papers, farming papers, and business magazines. As many Catholic immigrants arrived, major church areas started their own newspapers. For example, the Boston Pilot was a leading Irish Catholic newspaper.

Evangelical Protestants also used newspapers to discuss important topics like temperance (avoiding alcohol) and even votes for women. After 1830, the fight to end slavery became a very heated topic. The most famous anti-slavery newspaper was William Lloyd Garrison's Liberator, which first came out in 1831. It said slavery was a sin and needed to stop immediately. Many anti-slavery papers were blocked from being mailed in the South. Editors were attacked, and offices were destroyed. Some editors, like Lovejoy in Alton, even lost their lives.

Local Papers in Rural Areas

Almost every county seat and most towns with more than 500 people had one or more weekly newspapers. Politics was a big interest, and the editor often played a major role in local political groups. But these papers also had local news, stories, and book excerpts for readers.

A typical rural newspaper gave its readers important national and international news, often reprinted from bigger city newspapers. These papers reached many people, including property owners and a wide range of other citizens. Big city newspapers also often made weekly editions to send to the countryside. For example, the Weekly New York Tribune was full of political, economic, and cultural news. It was a key resource for political parties and a way for people to learn about the world. Later, the Rural Free Delivery program, which delivered mail to rural areas, helped daily newspapers reach even more people in the early 1900s.

Mass Markets and New Journalism: 1890–1920

This period saw the rise of new types of journalism that aimed for huge audiences.

Muckrakers: Exposing Problems

A "muckraker" is a term for a journalist who investigates and exposes corruption and other problems in society. In America, this term is usually linked to a group of investigative reporters, writers, and critics during the Progressive Era (from the 1890s to the 1920s). They looked into issues like political corruption, corporate crime, child labor, bad conditions in slums and prisons, unhealthy food processing, and fake claims by medicine makers.

Muckrakers wanted to help the public by uncovering crime, corruption, and waste in both government and private businesses. In the early 1900s, they wrote books and articles for popular magazines like Cosmopolitan and McClure's. Some famous early muckrakers include Ida Tarbell, Lincoln Steffens, and Ray Stannard Baker.

Here are some well-known muckrakers:

- Nellie Bly (1864–1922) wrote Ten Days in a Mad-House, exposing conditions in mental hospitals.

- Lincoln Steffens (1866–1936) wrote The Shame of the Cities (1904), about corruption in cities.

- Ida Minerva Tarbell (1857–1944) wrote an expose called The History of the Standard Oil Company, about a powerful oil company.

Yellow Journalism: Exciting News

Yellow journalism is a term for news reporting that uses sensationalism, exaggerated stories, or other unprofessional methods to attract readers.

The term came from the competition between Joseph Pulitzer's New York World and William Randolph Hearst's New York Journal from 1895 to 1898. Both papers were accused of making news more exciting to sell more copies, even though they also did serious reporting. The New York Press first used the term "Yellow Journalism" in 1897 to describe these papers.

Newsboys: The Front Line of Sales

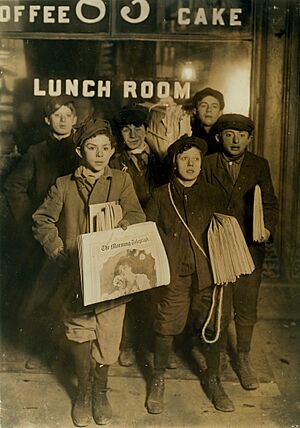

Exciting news made people want to buy newspapers. So, newspapers needed new ways to get copies to readers. They often relied on newsboys who sold individual papers on city streets. There were also newsstands that sold many different papers. Vending machines for newspapers appeared in the 1890s.

Home delivery became more important in the early 1900s, with paperboys delivering papers to subscribers. On busy street corners, several newsboys would sell different major newspapers. They might carry posters with giant headlines. After World War II, home delivery became the main way papers were sold.

Newsboys were not employees of the newspapers. They bought bundles of papers from wholesalers and sold them as independent sellers. They couldn't return unsold papers. Newsboys typically earned about 30 cents a day and often worked late into the night. They would shout "Extra, extra!" to sell their last papers.

The image of a teenage boy delivering papers on a bicycle became common in the 1930s. Newspapers needed to boost sales during the economic downturn. So, they created programs to teach boys how to sell subscriptions door-to-door. This helped create the image of the "middle-class newspaper boy" and changed how teenagers earned money.

Photographer Lewis Hine took pictures to expose child labor in factories and mines. But his photos of newsboys showed them differently. They were seen as independent young entrepreneurs, showing friendship and ambition. The newsboy became a symbol of youthful independence in America. Many famous Americans, like Thomas Edison and Harry S. Truman, were newsboys when they were young.

Newspapers for Different Groups: The Ethnic Press

While English-language newspapers served most people, almost every immigrant group had its own newspapers in their own language. Many immigrants in the 1800s moved to places like Minnesota, Nebraska, and Iowa. In these communities, local newspapers became a way to share political and religious ideas in familiar languages. Many of these papers also wanted to help their readers feel more American.

For example, Den Danske Pioner (The Danish Pioneer) helped Danish Americans take part in American democracy. This paper, based in Omaha, Nebraska, grew to have a circulation of 40,000 during World War I.

German publishers were very important in developing the ethnic press. By 1890, there were 1,000 German-language newspapers published each year in the United States. Before World War I, Germans were seen as a respected immigrant group. However, when America entered the war, opinions changed. Many Americans saw German newspapers as supporting Germany. In 1917, Congress passed laws that made it harder for foreign-language newspapers to publish. German papers almost all closed during World War I. After 1950, most other ethnic groups also stopped publishing foreign-language papers.

This decline in foreign-language papers during World War I affected many groups. In 1915, daily Yiddish newspapers had a circulation of half a million in New York City alone.

In Chicago, Polish Americans had many different newspapers, each supporting different political ideas. In 1920, they could choose from five daily papers, from socialist papers to those linked to the Polish Roman Catholic Union of America. These papers supported workers' rights and were part of broader cultural activities. Subscribing to a paper often showed a person's beliefs and community ties. Most of these papers encouraged immigrants to become part of American society and adopt American values, but they also included news from their home countries.

After 1965, there was a big increase in new immigration, especially from Asia. However, these groups started fewer major newspapers. By the 21st century, over 10% of the U.S. population was Hispanic. They often used Spanish-language radio and television, but outside large cities, it was harder to find Spanish newspapers or magazines.

Newspaper Chains and Syndicates: 1900–1960

E. W. Scripps started the first national newspaper chain in the United States in the early 1900s. He wanted to offer different types of content to appeal to his readers. Scripps believed that success meant providing what other newspapers didn't. To do this, he created a national wire service (United Press International) and a news features service (Newspaper Enterprise Association). This helped him reach a large audience at low costs. He especially attracted women, who were more interested in features than political news. However, local editors lost some control, and local news coverage became less detailed.

William Randolph Hearst also built a huge newspaper empire. He opened newspapers in many cities, including Chicago, Los Angeles, and Boston. By the mid-1920s, he owned 28 newspapers across the country, like the Los Angeles Examiner and The Washington Times. He also owned magazines, news services, and a film company. Hearst used his influence to help Franklin D. Roosevelt get nominated for president in 1932. However, he later disagreed with Roosevelt and his newspapers became strong opponents of the New Deal.

New Challenges: Television and the Internet, 1970–Present

Newspapers have faced big changes since the 1970s. A report from 2015 showed that the number of newspapers per person has dropped a lot. In 1945, there were 1,200 newspapers for every hundred million people, but by 2014, that number was only 400. The number of newspaper journalists has also decreased.

Other traditional news sources have also struggled. Since 1980, television news programs have lost half their viewers, and radio news audiences have shrunk by 40%.

As more people get their news from television and especially the internet, newspapers have had to adapt. This has led to a major business crisis for many newspapers, as readers and advertisers move online.

See also

- African-American newspapers

- History of journalism

- History of newspaper publishing

- German American journalism

- Irish American journalism

- Mass media and American politics

- Preservation (library and archival science), for preserving old copies

| Aaron Henry |

| T. R. M. Howard |

| Jesse Jackson |