Early American publishers and printers facts for kids

Early American publishers and printers were super important in shaping life in the American colonies, both before and during the American Revolution. In the 1600s and 1700s, printing first started because people really wanted Bibles and other religious books. Later, in the mid-1700s, newspapers became popular, especially in Boston.

When the British government started adding new taxes, many newspapers began to openly criticize the unfair rules. In the early days, news traveled slowly between the colonies, often by handwritten notes carried by people. Before 1700, there were no newspapers, so official news was hard to get, especially for people living far from big towns.

Religious books were also hard to find. Many colonists had Bibles they brought from England, but there weren't enough for everyone, and people really wanted more religious writings.

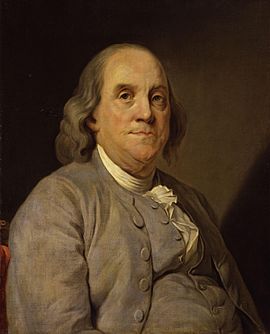

As the British government kept adding taxes, like the Stamp Act in 1765, newspapers and pamphlets started criticizing these rules strongly. Famous printers like Benjamin Franklin, William Goddard, and William Bradford were involved in these protests. They believed in freedom of the press and other rights. Some printers, like Goddard and Bradford, were part of the Sons of Liberty. They used their presses to speak out against the Stamp Act and other laws they felt were unfair. This open criticism often led to accusations of printing false or rebellious material.

Contents

Colonial Newspapers

Newspapers in colonial America helped share important political, social, and religious information. This news helped colonists feel more connected to each other. The government worried that spreading news and opinions widely would weaken their power. Boston was where American newspapers first started and grew. At first, newspapers were delivered by mail for free until 1758.

In the early 1700s, Boston had twice as many printers as the rest of the country. Out of only six American newspapers, four were published in Boston. Most books and pamphlets from that time were also printed in Boston, making it the center for writing and printing in colonial America.

Colonial newspapers played a big part during the Christian religious movement in the early 1740s. This movement started in Boston. Thomas Fleet used his Boston Evening Post to criticize the church leaders. Another newspaper, The Christian History, by Thomas Prince, also covered these topics.

The very first newspaper in the British colonies was Publick Occurrences Both Forreign and Domestick. It was printed in Boston on September 25, 1690, by Richard Pierce for Benjamin Harris. Harris had left England because he feared religious persecution and had spoken out against the king. Colonists liked his newspaper, but the colonial governor did not. It didn't have an official printing license, which was required by British law. Because of this, it was quickly shut down.

The first successful newspaper in America was The Boston News-Letter, which started in 1704. It was the only newspaper in the colonies until 1719.

The Boston News-Letter was printed by Bartholomew Green for John Campbell, who was the Postmaster in Boston. This newspaper had government approval and ran for 74 years until 1776, when the British took over Boston. The Hartford Courant is thought to be the oldest newspaper in the United States that has been published continuously.

Before the Stamp Act of 1765, there were 24 newspapers in the colonies. New Jersey got its news from newspapers in nearby Philadelphia and New York. By 1787, Thomas Jefferson believed strongly in freedom of the press. He said he would rather have newspapers without a government than a government without newspapers.

Many newspapers before and during the American Revolution were important for criticizing the government, promoting freedom of the press, and pushing for American independence. Newspapers were already essential to colonists for information. They saw printed news as a key way to keep everyone informed and to spread ideas of freedom. Newspapers also helped shape public discussions when the Constitution was being approved in 1787–1788.

Promoting Independence

The idea of an independent America began after the French and Indian War. At that time, the British government started taxing the colonies heavily to pay off war debts. By 1774, the idea was not yet to completely break away from England. People still thought the colonies would be part of the British Empire, under the King and Parliament.

However, after the Boston Tea Party in late 1773, the idea of the colonies having their own independent government started appearing in newspapers. Writers often stayed anonymous because they feared punishment. They promoted the need for an “American Congress” to speak for Americans. They insisted that this American Congress should have equal power with British authority. Newspapers like the Boston Gazette and The Providence Gazette were very active in publishing articles that encouraged American independence.

Selected Publications

The first magazine in the American colonies was The American Monthly Magazine, printed by Andrew Bradford in February 1741. The first religious magazine, Ein Geistliches Magazien, was published by Sower in 1764.

In 1719, the Boston Gazette was started in Boston. The first newspaper in Philadelphia, the American Weekly Mercury, was also founded by Andrew Bradford that same year. In 1736, the first newspaper in Virginia, the Virginia Gazette, was founded by William Rind. Rind soon became the official public printer. This newspaper printed Thomas Jefferson's A Summary View of the Rights of British America in 1774, two years before he wrote the Declaration of Independence.

Also in 1774, the Virginia Gazette reprinted the rules of the Continental Association. These rules were written and signed by members of the Continental Congress in response to the Intolerable Acts. They united the colonies in refusing to buy British goods and stopping exports to England. On April 22, 1775, three days after the Battles of Lexington and Concord, the Virginia Gazette reported that a lot of gunpowder had been stolen in Williamsburg by order of Lord Dunmore. This news spread quickly and was repeated in The Pennsylvania Evening Post. The news reports made Dunmore pay for the gunpowder, which helped avoid a fight in Virginia for a while.

The New-England Courant started on August 7, 1721. It was the third newspaper in Boston and the fourth in the colonies. James Franklin, Benjamin Franklin's older brother, started it in Boston. He did this after losing his printing job at the Boston Gazette. Benjamin Franklin wrote many articles for the paper using the fake name Silence Dogood. One article led to James Franklin being jailed for a month in 1726. British authorities arrested him for printing what they called rebellious articles after he refused to say who the author was. After he was released, James continued printing. His newspaper was ordered to shut down after only four months.

On October 2, 1729, Samuel Keimer, who owned The Pennsylvania Gazette in Philadelphia, sold it to Benjamin Franklin and his partner Hugh Meredith. Keimer had failed to make the newspaper successful and was in debt. Under Franklin, The Gazette became the most successful newspaper in the colonies. On December 28, 1732, Franklin announced in The Gazette that he had printed the first edition of The Poor Richard. This almanac was a huge success and was printed for over 25 years.

The first printing press made in America was built in Germantown, Pennsylvania, in 1750. In the same place, in 1772, Christopher Sower built the first proper factory for making printing type. However, its tools came from Germany and were only for German types. Salem was the third town in the colonies to get a public printing press.

On June 19, 1744, Franklin made David Hall his business partner and manager of The Gazette. This gave Franklin time to work on his scientific and other interests. When the Stamp Act was proposed, Hall warned Franklin that people were already canceling their newspaper subscriptions. They were doing this not because of the higher cost, but because they disagreed with the tax. After buying out Franklin in May 1766, Hall started a new company, Hall and Sellers. This company printed the paper money issued by Congress during the American Revolutionary War.

James Davis came to North Carolina in 1749. The local government had asked for an official printer to print their laws, legal documents, and paper money. He became the first printer to set up a shop in that colony. He also started and printed North Carolina's first newspaper, the North-Carolina Gazette. In 1755, Benjamin Franklin appointed Davis as North Carolina's first postmaster.

The first newspaper in Connecticut was The Connecticut Gazette in New Haven. It started on April 12, 1755, as a weekly newspaper published by James Parker. As the main newspaper in that colony, it recorded military events during the French and Indian War. Parker's partner was Benjamin Franklin, who often helped printers get started. That year, Parker also published ten religious pamphlets, five almanacs, and two New York newspapers. He rarely visited New Haven, leaving his junior partner, John Holt, as the newspaper's editor. The Gazette had a large readership throughout the Connecticut Colony for a while. It continued until 1764, then stopped briefly, but was later restarted by Benjamin Mecom. Its motto, printed on the front page, said: "Those who would give up Essential Liberty, to purchase a little Temporary Safety, deserve neither Liberty nor Safety." Like other newspapers of that time, The Gazette strongly criticized the Stamp Act.

The Providence Gazette was first published on October 20, 1762, by William Goddard, and later with his sister Mary Katherine Goddard. At the time, it was the only newspaper printed in Providence. The paper was published weekly and strongly defended the rights of the colonies before the revolution. It also supported the country's cause during the war. After American independence, it continued to promote republican principles.

The Pennsylvania Chronicle, published by William Goddard, first appeared on January 6, 1767. This was the fourth English-language newspaper in Philadelphia. It was also the first in the northern colonies to have four columns per page.

John Dunlap was asked by the Second Continental Congress to print 200 copies of the Declaration of Independence. These copies are known as the Dunlap broadsides. John Hancock sent a copy to General Washington and his army in New York, telling them to read it aloud.

The Pennsylvania Evening Post was a newspaper published throughout the American Revolutionary War by Benjamin Towne, from 1775 to 1783. It was the first newspaper to print the United States Declaration of Independence, and it was also the first daily newspaper in the United States.

By 1740, there were 16 weekly newspapers in the British colonies. By the time of the American Revolution in 1775, there were about 37 newspapers. Most of them regularly published articles promoting colonial independence from Britain.

Freedom of the Press

Many printers in England who published materials supporting the English Reformation fled to Europe or the New World. They wanted to escape religious and political punishment under King Henry VIII and Queen Mary I, who were trying to reverse the Reformation. John Daye, who printed Protestant writings, is a good example. At the same time, colonial governments needed to set up presses and appoint official printers for their laws. Salem was the third town in the colonies to get a printing press.

The invention of the printing press gave ordinary people a powerful tool to challenge the king's authority. The influence of the printing press grew quickly, despite efforts by rulers to censor it.

Before 1660, it was rare for someone to be punished for rebellious news in the colonies. But this changed in the late 1600s. Cases involving rebellious speech rose from 0.7% in the 1660s to 15.1% by the 1690s. Even if the information was true, these cases were increasing. Many writers felt they had to use fake names to avoid being punished and having their presses taken away.

Many printers were accused of rebellion and libel (printing false, harmful statements) for criticizing colonial authorities. The first major case of press censorship happened during the trial of Thomas Maule in 1696. He had publicly criticized the actions of Quakers during the Salem Witch Trials. He was the first person in the colony to be charged with libel for publishing his work, Truth Held Forth and Maintained. Maule was sentenced to ten lashings for saying that Rev. John Higginson "preached lies."

Newport, Rhode Island, became the fourth town in New England to have a printing press when James Franklin arrived in 1727. Franklin had moved to Newport from Boston because he had been jailed in 1722 for criticizing officials and religious leaders in his newspaper, The New-England Courant.

Another important case was the trial of John Peter Zenger in New York in 1735. He was tried for supposedly libeling Governor William Cosby. But Zenger was found innocent because his statements were true. This landmark case was a big step towards establishing freedom of the press in the colonies. The British government then felt that printing and publishing in the colonies was undermining their power.

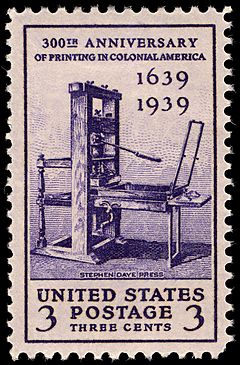

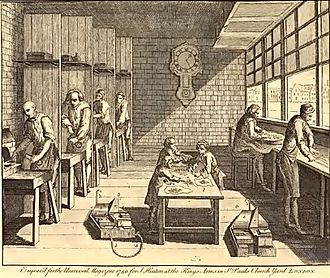

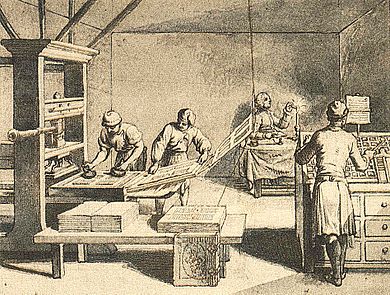

Printing technology didn't change much from the mid-1600s to the late 1700s, but its usefulness grew a lot. The first printing press arrived in the colonies in 1638 with British printer Stephen Daye. It was part of the founding of Harvard University. This press was set up to print religious works without interference from Parliament. Its first printing was the Freeman's Oath in January 1639. Many printers learned their trade at Harvard's printing office. Their books, pamphlets, and posters helped spread the Enlightenment movement in New England. Printing presses, books, and newspapers were mostly found in the northern colonies. Southern colonies were more controlled by the king or private owners and had less self-governance.

In 1752, Jonathan Mayhew, who started the Unitarian Church in America, openly criticized the Massachusetts colonial government. One of Mayhew's sermons, given during an election, strongly supported a republican form of government. His sermon was published just after the colonial assembly passed a bill adding new taxes. The bill was strongly attacked in a pamphlet from Samuel Adams' newspaper, The Independent Advertiser. The bill was called the "Monitor of Monitors," saying the government was being handled harshly.

After Mayhew's sermon was published, it caused alarm among colonial authorities. David Fowle, the printer, was arrested. He refused to say who wrote the newspaper article and was jailed and questioned for several days. Fowle became so upset with the Massachusetts government that he moved to Portsmouth. There, he bought New Hampshire Gazette, where he would publicly criticize the Stamp Act of 1765.

Religious Printing

Religious ideas became very important in colonial American writings in the late 1600s and 1700s. These were mostly found in Puritan writings and publications. This often led to charges of libel and rebellion from the British government. Puritans had already faced persecution in England for printing and sharing their views, which openly criticized the Church of England. In 1637, King Charles passed a decree that gave the government complete control over censoring any religious, political, or other writings they thought were rebellious. This decree made it illegal to criticize the Church of England, the State, or the government. It was very hard on minority groups like Catholics, Puritans, and separatists. The rules also allowed for punishment of illegal publications in the colonies, trying to silence the Puritans. Archbishop William Laud was especially strict about preventing unauthorized printing. However, by 1730, it became harder to enforce these rules in the colonies, which included licensing printing presses and approving literature before publication.

In 1752, Samuel Kneeland and his partner Bartholomew Green printed an edition of the King James Bible. This was the first Bible printed in America in English. It was illegal to print this Bible in America because the British Crown owned the printing rights. So, the printing was done as secretly as possible. The Bible had the London imprint of the copy it was taken from to avoid being caught. This made Kneeland the first to print a Bible from the Boston Press.

In 1663, English Puritan missionary John Eliot spent 40 years bringing about 1,100 Native Americans to Christianity. He set up 14 "praying towns" for his followers. Along with other religious works, he published what became known as the Eliot Indian Bible. Printed by Samuel Green, it was the first Bible published in the British-American colonies. It aimed to introduce Christianity to Native American peoples. Eliot's Bible was a translation of the Geneva Bible into the Algonquian language spoken by the Native Americans in Massachusetts.

Cotton Mather was a Puritan minister in New England and wrote many books and pamphlets. He is considered one of the most important thinkers in colonial America. Mather used the presses in New England often, sometimes to fight back against attacks on Puritans by George Keith and others. Between 1724 and 1728, he printed 63 titles on colonial presses. He is known for his Magnalia Christi Americana, published in 1702, which describes the religious growth of Massachusetts and other New England colonies from 1620 to 1698. To promote Puritan values, he wrote Ornaments for the Daughters of Zion, advising young women on proper dress and behavior. He became a controversial figure because of his involvement in the Salem witch trials of 1692–1693.

Jonas Green, a student of Benjamin Franklin in Philadelphia, was part of the Green family who ran presses in the Puritan colonies. For 28 years, Green was the official printer for the Province of Maryland. Joseph Galloway, a close friend of Franklin, was against the Revolution as a Tory. By 1778, he had fled to England. Like many Tories, he believed the Revolution was largely a religious disagreement, caused by Presbyterians and Congregationalists and the letters they printed.

Benjamin Franklin, who was raised Presbyterian and later became a Deist and then a non-denominational Protestant, understood the importance of printing and promoting religious values. He saw it as a way to strengthen society and unite the colonies against British rule. Franklin ended up publishing more religious works than any other American printer in the 1700s.

Thomas Dobson, who arrived in Philadelphia in 1754, was the first printer in the United States to publish a complete Hebrew Bible. Robert Aitken, a Philadelphia printer who arrived in 1769, was the first to publish the Bible and the New Testament in English in the newly formed United States.

The Christian History, a weekly journal, featured stories about the revival of religion in Great Britain and America. It was published by Kneeland & Greene, with Thomas Prince, Jr. as editor. It was issued regularly for two years, from March 5, 1743, to February 23, 1745. Prince also wrote other works, including his important 1744 book, An Account of the Revival of Religion in Boston in the Years 1740-1-2-3.

Colonial Taxation

After the expensive French and Indian War, Britain was deeply in debt. They started taxing their colonies without giving them a say in Parliament. This worried many colonists, who were already struggling financially. They felt they had already given a lot of lives, property, and money to a war fought mostly on American soil. Soon, their indifference turned into public protests and open rebellion. Publishers and printers began creating newspapers and pamphlets that clearly showed their anger and sense of injustice. Famous figures like James Otis Jr. and Samuel Adams were among the most vocal opponents of colonial taxation. Their ideas were spread through many colonial newspapers and pamphlets.

Boston was a center of rebellion before the American Revolution turned into a war. The Boston Gazette, started on April 7, 1755, by Edes and Gill, was known as the "pet of the patriots." Its pages featured New England's arguments for American freedom. It published opinions from men like Samuel Adams, Joseph Warren, John Adams, Thomas Cushing, and Samuel Cooper. They wrote about issues like the American Revenue Act of 1764, the Stamp Act of 1765, the Boston Massacre, and the Tea Act. These were widely seen as unfair impositions on the colonies.

Stamp Act

When the Stamp Act passed in 1765, it put a tax on newspapers, advertisements, legal documents, and more. Printers began publishing strong articles criticizing the Act. This often led to accusations of rebellion and libel from royal authorities. Newspaper printers and publishers felt the new tax would greatly increase their costs. They worried it would cause many readers to cancel their subscriptions. Many newspaper editors protested by printing editions with black borders. They often included articles that strongly mocked the Stamp Act. Some newspapers even printed a skull and crossbones where a royal stamp was supposed to appear.

The Act also made many printers stop publishing rather than pay what they felt was an unfair tax. This united them against the law. Newspapers were the main way to put social and political pressure on the Stamp Act. They were key to its repeal less than a year later.

For example, The Constitutional Courant was a single newspaper issue published to protest the Stamp Act. Printed by William Goddard under the fake name Andrew Marvel, it strongly attacked the Stamp Act. This caught the attention of both colonial printers and royal officials. Another example was The Halifax Gazette, which also published a very critical article. It stated that "The people of the province were disgusted with the stamp act." This paragraph greatly offended the royal government, and its publisher, Anthony Henry, was questioned for printing what the Crown considered rebellious.

The Sons of Liberty actively scared off royal officials who were supposed to collect the taxes. As newspapers continued to openly criticize the Stamp Act, protests spread, often violently. This caused many tax collectors across the colonies to quit their jobs. Benjamin Franklin, who was representing the colonies in London, had warned Parliament that the Act would only create bad feelings between the colonies and Britain. After much protest, the Act was repealed in 1766. Newspaper coverage of the Stamp Act and public protests marked the first serious challenge by the colonists to British rule.

Townshend Acts

After the Stamp Act failed and was repealed, the Townshend Acts were passed by Parliament in 1767. These acts, introduced by Charles Townshend, included The Revenue Act of 1767. Passed on June 26, 1767, this act again taxed paper, along with lead, glass, and tea. In October, the text of the Revenue Act was widely printed in newspapers, often with critical comments. Like the Stamp Act, this new tax directly threatened printers' businesses and livelihoods. Printers relied on paper for printing and lead for making printing type. The Act specifically put import taxes on 67 different types of paper.

Soon, newspapers like the Boston Gazette and Pennsylvania Chronicle began publishing essays and articles against the Townshend Acts. One of the most famous works criticizing the Acts was Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania, written by John Dickinson. These 12 letters were widely read and reprinted in many newspapers across the 13 colonies. They played a major role in uniting the colonists against the British government and its constant taxing. William Goddard was the first printer to publish Dickinson's work. Dickinson wrote that these essays "deserved the serious attention of all North-America." Dickinson's work was also published by printers like David Hall and William Sellers. These printers used their presses to publicly challenge such acts.

The new tax also encouraged the building of papermills in the colonies and for colonists to produce their own goods. However, in the years leading up to the revolution, paper became scarce. There were few papermills, and they were small, with limited production. As imports decreased, the need for colonists to make their own goods increased greatly. To save paper, newspapers were printed in the smallest possible size, with little room for borders. In other cases, weekly newspapers stopped publishing because they couldn't make enough money with the new taxes and paper shortages.

American Revolution

David Ramsay, an early historian of the American Revolution, said that "the pen and press had merit equal to that of the sword" in achieving American independence. In the years before and during the Revolution, hundreds of pamphlets were printed. They covered topics like religion, law, politics, natural rights, and the Enlightenment, all related to revolutionary ideas. Historian Bernard Bailyn explains that these pamphlets showed the true reasons behind the revolution. He notes that these reasons sometimes differed from what many historians usually say.

For years, historians have debated how much religious ideas influenced the American Revolution. However, it's clear that many religious writings often promoted ideas of freedom of speech and press, and other liberties. They openly criticized the British government for what they saw as attacks on their God-given rights. These issues were key to starting the revolution. Because of this, colonial authorities were always watching for any statements in religious publications that they felt were rebellious.

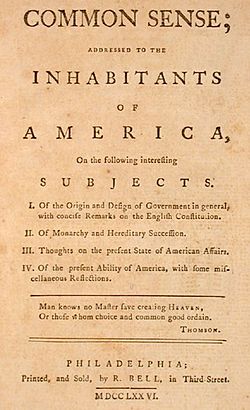

In the years just before the war, Massachusetts was a leader in the Revolution. Royal authorities considered Boston a "hot-bed of sedition" (a place full of rebellious ideas). During this time, printers and publishers were very important in spreading the call for independence and uniting the American colonies. Thomas Paine's 1776 work, Common Sense, explained moral and political arguments. It is considered "the most powerful and popular pamphlet of the entire revolutionary era." It was printed by Robert Bell. In response to Paine's work, James Chalmers, using the fake name Candidus, wrote a pamphlet called The Plain Truth. This was also printed by Robert Bell. But it was not well-received by patriotic people, who forced Chalmers to leave the country.

The ideas of "Patriot" (supporting independence) and "Loyalist" (supporting Britain) weren't fully clear until 1774. That's when independence became the main political and social issue. Many printers believed in a free press. They thought printers shouldn't take sides but allow a "free and open press" where different political ideas could be openly discussed.

Newspapers greatly helped unite the separate colonies. They appealed to their shared desire for liberty. Before the ideas of independence and revolution became popular, the colonies had many differences in their settlements, governments, religions, cultures, and trade. Benjamin Franklin, who understood the situation well, said that only oppression of the whole country would ever unite them. He believed colonists needed to understand that their rights as people were more important than the rights allowed in a specific colony. Samuel Adams also realized this in 1765. He said Americans would never unite and fight for independence "unless Great Britain shall exert her power to destroy their Libertys." Newspapers like the Boston Gazette (which also printed titles of new religious books) and the Massachusetts Spy were key in spreading ideas that bridged the religious, cultural, and political differences between the colonies.

Before the revolution, printing was mostly done in the capitals of the different colonies. During the war, however, many printers and publishers moved their operations to other towns. This made it less likely for their presses and shops to be taken or destroyed by British forces. After independence was finally achieved with the peace of 1783, printing presses and newspapers grew very quickly. They appeared not only in port cities but also in almost all major inland villages and towns.

Two main types of printed materials influenced political developments during the American Revolution: pamphlets and newspapers. Pamphlets became an important way to share revolutionary ideas during arguments between the colonists and the British Crown. They were often written by famous writers using a fake name. Scholars have called them the main drivers of change during the revolutionary era.

When the war started at Lexington and Concord in April 1775, it became clear that the Patriots (Whigs) controlled the press and postal networks. They could use these to spread their ideas and counter Loyalist arguments. Printing and publishing of Loyalist propaganda was then limited to cities and areas under British military control. After the Declaration of Independence was officially sent to the British Crown, only 15 Loyalist newspapers appeared at different times and places. But none of them managed to publish continuously during the unstable war years from 1776 to 1783. British-occupied New York City had the longest-running and most popular Loyalist newspapers, including Hugh Gaine's New-York Gazette and the Weekly Mercury. Others included The Massachusetts Gazette, the main Tory newspaper, published by Richard Draper, and Alexander Robertson's The Royal American Gazette, James Rivington's Royal Gazette, and William Lewis's New York Mercury. Rivington clearly sided with the British. Gaine, like many Loyalists from the southern colonies, felt sympathy for colonial rights but disliked open rebellion and violence. Neither of these printers became strong supporters of the British cause until the actual war started. British occupation of New York City made it almost impossible to stay neutral. After 1770, as tensions with England grew, Loyalist newspapers lost most of their advertisers.

Printers provided a very valuable service to statesmen, important patriot figures, and the Continental Congress. They spread their political and social views and other news before and during the war. In the fall and winter of 1768, Samuel Adams of Boston was busy writing for various newspapers, mostly the Boston Gazette. The Gazette was his main way to share his voice and a meeting point for patriot leaders. The newspaper was known for its sharp, well-written articles about the unfair things happening in the colonies. Adams wrote passionate articles about the revolutionary cause through this newspaper.

Adams contributed a powerful letter on December 19, 1768, to this newspaper. According to historian James Kendall Hosmer, it showed the "superior political sense of the New Englanders." In it, Adams attacked the British Parliament over the issue of taxation without representation. He argued that "what is a man's own is absolutely his own, and that no man can have a right to take it from him without his consent." The office of the Boston Gazette on Court Street also served as a meeting place for revolutionary figures like Joseph Warren, James Otis, Josiah Quincy, John Adams, Benjamin Church, and other important patriots. Many of these figures were typically part of the Sons of Liberty. In these groups, Samuel Adams became more and more a strong and important figure, and his writings were also published in newspapers far away.

John Dunlap, who founded The Maryland Gazette, was one of the most successful Irish-American printers of his time. He printed the first copies of the United States Declaration of Independence and A Summary View of the Rights of British America by Thomas Jefferson. In 1778, Congress asked Dunlap to print the Congressional Records. For five years, he continued as their official printer. Dunlap and his partner David Claypoole printed the Articles of Confederation. They promised Congress, "...that we will not disclose either directly or indirectly the contents of the said confederation."

Mathew Carey was one of several printers who came to the American colonies to escape punishment. He had printed and published the Volunteers Journal, a Dublin newspaper that supported the anti-British Volunteer movement. The British Crown considered this rebellious writing.

In 1777, the Continental Congress asked Mary Katherine Goddard to print copies of the Declaration of Independence for distribution among the colonies. Many of these copies were signed by John Hancock, President of the Congress, and Charles Thomson, Permanent Secretary. They are now highly valued by historians and collectors.

Post Revolution

After the Revolutionary War ended, the Patriot victory at the Siege of Yorktown was widely covered by both American and British newspapers. Before, during, and after the battle, news spread. The Massachusetts Spy, just a week before the battle on September 13, 1778, wrote:

"It is not doubted but that his Excellency General Washington has marched,with 8000 choice troops including the French, to Virginia, where the troops in that quarter will join him; Lord Cornwallis is blocked up by the French fleet;—by the present appearance of things we are at the eve of some important event, which God grant may be propitious to the United States”.

After the Patriot victory at Yorktown, there were many newspaper reports covering the three-week campaign. Some reports even appeared months later as new information became available. The first reports were based on accounts from various commanders. The report in the Independent Chronicle on April 19, 1781, was generally informative but based on a hurried report by Nathanael Greene, who didn't have complete information on troop numbers and casualties. The report from Lord Cornwallis, which appeared in the London Chronicle on June 7, 1781, also had several errors. However, newspaper coverage featured many important commanders. The general reports of the victory boosted the morale and hopes of the Americans, while it did the opposite for the British.

After the revolution, it became clear that the new United States was politically disorganized. It needed to unite under one central government. Under the Articles of Confederation, the United States had little power to defend itself internationally. It couldn't call state militias together for war. It also lacked the power to collect taxes and failed to unite the different feelings and interests of the individual states. Uniting the states was a politically complex and difficult task. Many state politicians cared more about their state's independence. They were very cautious about a central authority, remembering the problems they faced with the British government. When the idea of a national constitution was suggested, it got mixed reactions from Federalists and Anti-Federalists. They often shared their views through newspapers and pamphlets.

To convince people in New York and other states that approving the U.S. Constitution was a good idea, Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay wrote a series of essays called The Federalist Papers. When they were first printed in New York newspapers, they were signed anonymously as Publius. Various essays began appearing in 1787 in New York's Daily Advertiser and The New York Packet. The Federalist articles were widely read and are often thought to have greatly influenced the approval process and future American political systems. The Federalist papers were challenged by the strong writings of Richard Henry Lee and Elbridge Gerry. This further showed how important the press was in achieving political goals. At this time, John Fenno became a Federalist Party editor through his newspaper, the Gazette of the United States. Alexander Hamilton regularly contributed pro-Federalist essays and money to this paper. It strongly supported the Constitution and the growing Federalist party.

On the Anti-Federalist side, Philip Freneau was a strong voice through his newspaper, the National Gazette. He started it in 1791, during President Washington's first term. James Madison and Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson encouraged Freneau to start what became a partisan newspaper. Its goal was to counter Federalist-leaning newspapers. Since Jefferson had hired Freneau as a French translator at the Department of State, some Federalists assumed Jefferson helped write the political attacks on Washington and his Federalist colleagues in Freneau's Gazette. Jefferson denied this. Washington generally didn't pay much attention to the political schemes in newspapers. However, he privately asked Jefferson to remove Freneau from the State Department. Jefferson insisted that Freneau and his paper were saving the country from becoming a monarchy. He convinced Washington to let Freneau stay, arguing that removing him would be an insult to Freedom of the Press and would harm Washington's administration. Both Fenno and Freneau became major figures in American newspaper history after the revolution. They played leading roles in shaping the beginning of party politics in the 1790s.

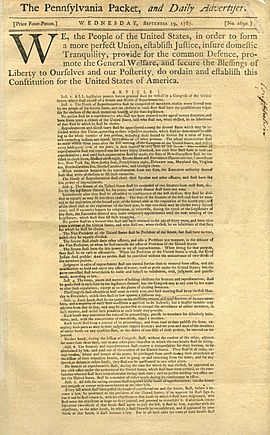

In 1787, Dunlap was asked to print copies of the Constitution of the United States on September 19, 1787, for review at the Constitutional Convention. He later published it for public review for the first time in The Pennsylvania Packet.

On April 30, 1789, George Washington took the oath of office as the first President of the United States in Federal Hall in New York City. After the ceremony, Washington entered the Senate chamber and gave the first presidential inaugural address. The entire event and speech were covered in an eyewitness report on May 6, 1789, in the Massachusetts Centinel. Towards the end of President Washington's second term, he decided to resign and declined offers to run for a third term. With help from James Madison and Alexander Hamilton, Washington, then 64, wrote his Farewell Address. He never read the Address publicly but had it published in newspapers in Philadelphia, which was the capital of the United States at the time. The Pennsylvania Packet and American Daily Advertiser was the first newspaper to carry the address in its issue of September 19, 1796. Soon, the famous Farewell Address was widely circulated and reprinted in many newspapers, including the New York Herald on September 21, 1796.

Newspapers and the U.S. Constitution

Before and after the U.S. Constitution was approved, newspapers everywhere featured news and essays about its development and content. Editorials about its strengths and weaknesses were common. They often started or fueled debates in town meetings, as well as in streets, taverns, and homes.

While the proposed U.S. Constitution was being debated by Congressmen and other political figures, and during its approval, many newspapers and pamphlets, mostly supporting the Constitution, worked hard to cover and report on the many details discussed. This process revealed geographical and political differences, dividing the press and much of the population into two political groups: Federalists and Anti-Federalists. Several newspapers that had long supported American independence now hoped to delay or even prevent the adoption of a Federal Constitution.

About six newspapers published articles that were very critical of the Constitution. They mostly argued that it was another form of central government that would weaken the power of the states. One such newspaper, The Boston Gazette, which had previously strongly supported American independence, was bitterly opposed to a Constitution. From that point on, it slowly lost many readers and stopped publishing by 1798. Other newspapers remained politically neutral and allowed all points of view to be published. However, the majority of newspapers supported a Constitution and a strong federal government. They believed such a government would unite the states and ultimately make them stronger. The Massachusetts Spy of Boston supported a Constitution, but because it was in an Anti-Federalist community, it faced much disapproval. Some supporting newspapers, however, would not allow any Anti-Federalist material to be published. This led to many complaints about attacks on freedom of speech and freedom of the press.

Later, in 1789, during its first session under the new Constitution, Congress drafted and introduced a national Bill of Rights. This was to be added to the Constitution and stated that Congress would not be allowed to make any law "abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press."

After the Constitution was approved, political leaders found they needed their own public platforms to express their views. This led to them splitting into different parties, which ordinary citizens often didn't know much about. To convince people to take sides on political issues, they founded partisan newspapers. These papers offered little general news and mostly focused on supporting the political ideas of their party leaders. This made them more like political pamphlets than sources of general news.

After the Constitution was adopted, the Senate floor was closed to reporters and other observers for several years. Congress, however, invited any onlookers the public gallery could hold. The relationship between journalists and politicians was not friendly. Reporters often complained that House members spoke quickly and continuously, often turning their backs and not speaking clearly, while reporters tried to write down as much as they could. Congressmen, in turn, claimed they were often misquoted or had their statements intentionally twisted, leaving out key points or important names. On September 26, 1789, House members began debating a resolution introduced by South Carolina representative Aedanus Burke. It accused newspapers of "misrepresenting these debates in the most glaring deviations from the truth" and for "throwing over the whole proceedings a thick veil of misrepresentation and error." However, two days earlier, the House had approved the final draft of the First Amendment in the Bill of Rights, which guaranteed journalists the right of freedom of the press. It's ironic that the details of the Congressional debates come from those same reporters. The "single best resource" for the early proceedings, in The Annals of Congress, was put together from accounts found in early newspapers.

The debates during the approval process, according to historian Richard B. Bernstein, showed "the American people at their political and principled best, albeit occasionally at their factional worst." However, despite all the coverage by reporters and newspapers, the approval process never received a full historical study at the state level, as a whole, until the 21st century. Much of the problem was that debates in some states were never recorded. Also, published debates were sometimes limited by the skills of reporters and their note-takers. Reporters often didn't want speakers to correct the wording of their speeches as they were being recorded. Many also showed a bias towards the Federalists, who often hired people to write and publish the speeches used during the debates. In the late 1980s, James H. Hutson listed problems with the records kept during the various state approval conventions. By the end of 2009, the Documentary History of the Ratification of the Constitution (DHRC) had published 14 volumes on the approval process in eight states. This was largely put together from, and by comparing, newspaper accounts of the time.

Newspapers and the Alien and Sedition Acts

The Alien and Sedition Acts were four laws passed by the Fifth U.S. Congress under President John Adams in 1798. This was during an undeclared war with France, called the Quasi War. The government claimed these laws were aimed at the French and their supporters in the United States. However, much of the reason for passing these Acts was because partisan newspapers were strongly criticizing President Adams and other Federalists. These critics felt Adams was too eager to go to war with France. The laws severely limited public criticism of government officials, especially in newspapers. They also made it harder for immigrants to become citizens. The Democratic-Republicans believed the laws were a political trick to silence the growing criticism in newspapers and during public protests.

The Federalists mostly supported the Acts. This led to the arrest and imprisonment of several newspaper editors, many of whom were very critical of Adams' administration. Even a critic of Thomas Jefferson, a strong Anti-Federalist, was arrested and jailed. Washington, who was often criticized by the Anti-Federalist press, also disagreed with the Acts. The Acts also made it harder for immigrants to become U.S. citizens through the Naturalization Act of 1790. It required immigrants to live in the U.S. for 14 years to become a citizen. This was said to be aimed at French and Irish immigrants, who might become citizens, to reduce their influence in avoiding war with France. The Acts also allowed the president to imprison and deport any non-citizen who was seen as a threat to the nation's stability.

The Federalists argued that the bills would strengthen national security during a war with France. Critics of the Acts, especially newspaper editors, claimed they were mainly an attempt to silence Anti-Federalist newspapers and discourage voters who disagreed with the Federalist party. They argued that the Acts violated the right to freedom of speech and freedom of the press, which are in the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. In trying to control a press that seemed out of control, the Acts only made things worse.

Facing these new laws, the freedoms enjoyed by the press, which once helped unite the colonies, were now being questioned by the government. Soon, the press became a source of political division. Both Federalists and Republicans felt that newspapers were being used to spread political scandals and lies instead of the truth in politics and society. Benjamin Franklin Bache, through his newspaper, the Philadelphia Aurora, published what were considered harsh attacks on the Federalist Party, especially on President John Adams and his predecessor George Washington. This almost caused riots in Philadelphia. Bache was charged with libel for this. Among other things, Bache, through his newspaper, accused Adams of being a warmonger, a "tool of the British," and "a man divested of his senses," who was trying to start a war with France. His frequent newspaper attacks on a sitting president, along with others, are often seen by historians as having greatly contributed to the passage of the Alien and Sedition Acts.

In the November 22, 1798, issue of the Philadelphia Aurora, Bache published this in response to the Acts:

"Who would have believed it, had it been foretold, that the People of America,

after having fought seven long years to obtain their Independence, would, at this early day,

have been seized and dragged into confinement by their own government ..."

There were 14 charges of libel under the Acts, all against Republicans, most of whom were newspaper editors. Pennsylvania Chief Justice Thomas McKean, in a 1798 libel case against William Cobbett, publisher of the Peter Porcupine's Gazette in Philadelphia, which was seen as a scandalous publication, once said:

"Every one who has in him the sentiments either of a Christian or a gentleman cannot but be highly offended at the envenomed scurrility that has raged in pamphlets and newspapers printed in Philadelphia for several years past, insomuch that libelling has become a national crime, and distinguishes us not only from all the states around us, but from the whole civilized world.

Historian Douglas Bradburn says that popular history often suggests that Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, who wrote the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions, were the main opponents of the Alien and Sedition Acts. However, he also notes that while this is largely true, that idea alone can be misleading. Opposition to the Acts was widespread and crossed political, religious, and social lines.

The enforcement of the Acts, which were federal laws, directly questioned the right of states to defend people's natural rights. This reflected the common beliefs about natural rights that emerged before and during the American Revolution. Opposition to the Acts quickly spread in most states during the latter half of 1798. These feelings were shared and amplified by a growing number of partisan newspapers. These papers played a central role in expressing general disagreement. They also encouraged an increasing number of public protests, which eventually led to a national petition drive against the Act. At first, signatures came slowly, but as word spread, they began coming in "streams and torrents," with thousands of signatures from different states, "flooding the floor of Congress." This greatly upset the Federalists.

Resistance to the Federalist Acts began almost at the same time in Virginia and Kentucky. This was with the introduction of the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions, secretly written by Jefferson and Madison, respectively. Their ideas stated that the Acts were unconstitutional and that states had the right to consider them invalid if they felt it was necessary. News of the growing opposition in Kentucky soon reached the eastern coastal states and was widely covered in their newspapers. Editor William Cobbet, however, mocked the effort in his Porcupines Gazette. He condemned the Kentucky petitioners as uneducated farmers, no better than "savages." Meanwhile, newspapers sympathetic to the Republicans celebrated the idea that the Kentucky resolutions clearly showed that the founding principles of the Revolution were still alive in America. The Lexington Kentucky Gazette called for organized resistance to the Acts and to the rush to war with France. Before the laws were even enacted, it called for meetings, committees of correspondence, and general mobilization to take place on the Fourth of July.

Jefferson went further than just basing his opposition to the Acts on states' rights. He put human rights first. Within a week, newspapers were publishing articles and statements about states' and individual rights. These were widely circulated, asserting the idea that the people and the states had the right to defy laws they considered unconstitutional. During 1798–1799, newspapers continued to push ideas that would prevent Adams from getting a second term. They also worked to reverse the Federalist majorities in Congress and many states, ending the centralization that the Federalists had designed. This led to a virtual end of the Federalist Party, paving the way for the Republicans and Jefferson's presidency, with a corresponding increase in Republican-leaning newspapers.

As public opposition to the Alien and Sedition Acts grew, it significantly contributed to Jefferson's victory over Adams. This resulted in the Democratic-Republican Party gaining a large majority in Congress during the presidential election in 1800. The new Congress never renewed the Act, which was allowed to expire on March 3, 1801, under its own rules. President Jefferson, who had always insisted that the Acts were an insult to freedom of speech and of the press, granted pardons to everyone presumed guilty of rebellion and libel under this Act. This greatly strengthened the idea of freedom of the press in the courts and in the public's view.

Printing Presses and Type

Before a printer could start a printing business, they needed to get money for a printing press and type. Both were expensive and hard to find. In the late 1600s and early 1700s, most printing supplies came from England. This added to the cost and made it difficult for new printers to set up shop. Factories for making type didn't appear in the colonies until the mid-1700s. It wasn't until 1775 that different types of printing fonts became easily available. Historian Lawrence C. Wroth, in his 1938 book The Colonial Printer, describes the different types of print available from the late 1600s to 1770.

Just like with printing presses and newspapers, there were laws in England that limited the number of factories allowed to make type. In 1637, a decree said that only four people in England could run a type foundry at any time. Each foundry was also limited in how many apprentices it could have. By 1693, this decree had ended, but the number of foundries still didn't increase much. Even English printers often had to get type from Dutch factories. Because of this, no printing presses existed in the colonies until the first one arrived in Cambridge from London in 1639. In the colonies, like in England, much of the type used by printers came from Dutch factories. Many examples of Dutch type can be seen in printed works from the colonies between 1730 and 1740.

Until the mid-1700s, printing presses used in the colonies were imported from England. It was hard to make the iron screw needed for the press, so American printers had no choice but to buy them from abroad. Isaac Doolittle, a clockmaker and skilled craftsman, built the first printing press made in America in 1769. It was bought by William Goddard.

The first printing types in the colonies came from type foundries in Holland and England. Some important type founders and designers included William Caslon (1693–1766) and John Baskerville (1707–1775). Both were leading printers in England during their time. Their typefaces greatly influenced how English type looked. They were the first to create an English national printing style, which then affected printing in the English-American colonies. Caslon typefaces quickly became popular among colonial printers from the mid-1700s until the American Revolution. While in Europe, Benjamin Franklin bought hundreds of pounds of type from the Caslon family for his presses in Philadelphia and other cities. He first used Caslon type when printing The Pennsylvania Gazette in 1738. Books, newspapers, and broadsides were mostly printed in Caslon old style types. Many important printed works also used Caslon type, including the first printed version of the Declaration of Independence by John Dunlap in 1776.

Bookbinding

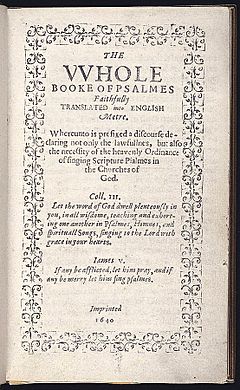

Bookbinders were also important in the printing and publishing business. Unlike newspapers and pamphlets, large printed works had many pages that needed to be bound into a book. This was done using a bookbinding press and required special skills from a bookbinder. The first recorded book printed on an American press that needed bookbinding was The Whole Book of Psalms, published in Cambridge in 1640. John Ratcliff from the 1600s is the first known bookbinder in colonial America. He is credited with binding Eliot's Indian Bible in 1663.

Some booksellers and publishers, like William Parks, Isaiah Thomas, and Daniel Henchman, did their own bookbinding. However, bookbinders were generally not well-known by name for the books they bound. There were very few cases where a bookbinder's name was included with the printer's on the title page or inside cover. A few books bound by Andrew Barclay of Boston are some of the known examples that include the bookbinder's name on a label.

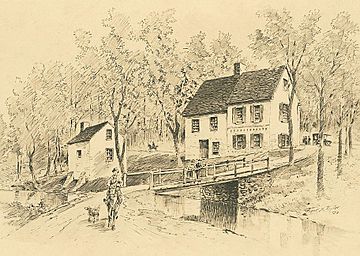

Paper Production in the Colonies

Making paper was essential for the printing and publishing industry, especially for newspapers. Many people helped collect linen rags, which were used to make paper. Before 1700, there were no newspapers in the colonies, so paper wasn't in high demand. Books were rare and usually brought from overseas. The first printing presses were set up in Cambridge, Massachusetts Bay colony, in 1638, and others soon appeared in New York, Boston, and Philadelphia. But the total amount of printed material was small. As the 1700s continued, more printing presses and newspapers started, and soon printers felt a paper shortage.

William Rittenhouse, with his partner William Bradford, established the first paper mill in colonial America in 1690. It was on Monoshone Creek, a small river north of Philadelphia. It was the only paper mill in the colonies for 20 years. The Rittenhouse family also built other paper mills, with their last one built in 1770.

The second paper mill in America was built by William De Wees, another settler of Germantown. He was the brother-in-law of Nicholas Rittenhouse, William's son, who had been an apprentice at the Rittenhouse mill. The third paper mill was started by Thomas Wilcox on Chester Creek, in Delaware county, 20 miles from Philadelphia. Wilcox had tried to find work at Rittenhouse's paper mill, but paper production was still new and business was slow. After saving money for some years, he managed to start his own paper mill in 1729.

Thanks to Daniel Henchman, the first paper mill north of New Jersey appeared in 1729 at Milton on the Neponset River. However, the paper shortage worsened in the years leading up to the American Revolution and became serious when the war finally broke out. Benjamin Franklin and William Parks established a paper mill in Williamsburg, Virginia in 1742, the first in the Virginia colony. Before 1765, most of the paper used by colonial printers had to be imported from England. The existing colonial paper mills, mostly in Pennsylvania, couldn't provide enough to meet the growing demand.

Benjamin Franklin was active in organizing the collection of rags used for papermaking. His sales of this material to paper makers, along with his sales of paper to colonial printers, grew very large. His contributions and advice made him a major factor in colonial papermaking and trade. Franklin took a special interest in paper production in the colonies, especially in Pennsylvania. He is credited with starting 18 paper mills in that area. Later, Delaware County in Pennsylvania became the center for paper mills in the late 1700s. Franklin, as a writer, often wrote about the importance of papermaking and how it was essential to the printing and publishing industry. In June 1788, he read a paper to the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia called, "Description of the Process to be Observed in Making Large Sheets of Paper in the Chinese Manner, with one Smooth Surface."

When the colonial assemblies passed nonimportation agreements in 1769, following the Stamp Act in 1765 and the Townshend Acts in 1767, the shortage soon became serious. By 1775, the existing supply of imported paper was almost gone. The 53 colonial paper mills were not enough to meet the demand. This situation prompted colonial governments, and even the Continental Congress, to take action to increase paper production. Various newspapers also helped by encouraging colonists to collect linen rags. They offered a bonus in addition to the value of the rags for those who brought in the most each year. Eventually, paper would be made from sawdust, but this and other major innovations in papermaking didn't happen until the 1790s.

"Laid Paper" and "Wove Paper"

The three main things absolutely needed for printing and publishing were the printing press, ink, and paper. Sometimes, any of these items could be hard to get—especially paper, which required a paper mill and a skilled team to make it. The paper made in the American colonies for most of the 1700s was called "laid paper." This was different from "wove" paper, which came into use later in that century. When held up to the light, laid paper showed many fine lines running the length of the sheet. These were crossed at about one-inch intervals by coarser lines, called "chain" lines. These impressions were formed by the bottom of the mold, where fine wires ran from end to end and were held firmly in place by coarse wires that crossed the mold from side to side.

It wasn't until 1757 that the British type designer John Baskerville invented his "wove paper." This was made by a mold with tightly woven fine brass wires, which produced a much smoother paper. It didn't have the wire lines and chain lines found in laid paper. The smoother paper allowed for clearer printing. Wove paper was regularly used in England soon after its invention and became popular with printers who made fine books. In 1777, Benjamin Franklin got some of this wove paper and brought it to France, where he introduced it to various people. By 1782, it was being successfully made in France. Wove paper was soon produced in the paper mills of the now independent United States. The earliest known use is found in examples by Isaiah Thomas in Worcester, in 1795. After that, it quickly became common among most American printers.

Prominent Early American Printers and Publishers

- Jane Aitken 1764–1832

- Robert Aitken (publisher) 1734–1802

- Francis Bailey (publisher) 1744—1817

- Robert Bell (publisher) 1725–1784

- Andrew Bradford 1686–1742

- William Bradford (printer, born 1663) 1660–1752

- William Bradford (printer, born 1719) 1719–1791

- John Campbell (editor) 1653–1728

- Mathew Carey 1760–1839

- John Carter (printer) 1745–1814

- Francis Childs (printer) (1763–1830)

- Isaac Collins (printer) 1746–1817

- James Davis (printer) (1721–1785)

- John Day (printer) 1522–1584

- Stephen Daye 1594–1668

- Gregory Dexter (1610–1700)

- Thomas Dobson (printer) 1751–1823

- John Dunlap 1747–1812

- Benjamin Edes 1732–1803

- John Fenno 1751–1798

- Thomas Fleet (printer) (1685–1758)

- Daniel Fowle (printer) 1715–1787

- Benjamin Franklin 1705–1790

- James Franklin (printer) 1697–1735

- Philip Freneau (1752–1832)

- Hugh Gaine — 1726–1807

- Sarah Updike Goddard 1701–1770

- Mary Katherine Goddard 1738–1816

- William Goddard (publisher) 1740–1817

- Bartholomew Green Sr. (printer) 1666–1732

- Samuel Green (printer) 1614–1702

- Jonas Green early 1700s–1767

- David Hall (printer) 1714–1772

- Nicholas Hasselbach (1749–1769)

- Anthony Haswell (printer) 1756–1816

- Daniel Henchman (publisher) 1689–1761

- John Holt (publisher) 1721–1784

- James Humphreys (printer) 1748–1810

- William Hunter (publisher) early 1700s–1761

- Samuel Keimer 1689–1742

- Samuel Kneeland (printer) 1696–1769

- Samuel Loudon (1727–1813)

- Hugh Meredith 1697–1749

- James Parker (publisher) 1714–1770

- William Parks (publisher) 1699–1750

- Richard Pierce (publisher) ?-1691

- Alexander Purdie (publisher) 1743–1779

- William Rind 1733–1773

- Clementina Rind 1740–1774

- James Rivington 1724–1802

- Joseph Royle (publisher) 1732–1766

- Benjamin Russell (journalist) 1761–1845

- Christopher Sower (elder) 1693–1758

- Christopher Sower (younger) 1721–1784

- Christopher Sower III 1754–1799

- Solomon Southwick (1773–1839)

- William Strahan (publisher) 1715–1785

- Isaiah Thomas (publisher) 1749–1831

- Ann Timothy 1727–1792

- Elizabeth Timothy 1700–1757

- Louis Timothee 1699–1738

- Peter Timothy 1724–1782

- Benjamin Towne mid 1700s–1793

- William Williams (printer and publisher) 1787–1850

- Thomas Whitemarsh (printer) (? – 1733)

- John Peter Zenger 1697–1746

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |