Physical history of the United States Declaration of Independence facts for kids

The physical history of the United States Declaration of Independence tells the story of how this super important document was made and kept safe over time. It includes the very first ideas written down, handwritten copies, and the first printed versions. The Declaration of Independence is a famous paper that said the thirteen colonies were now "Free and Independent States." This meant they were no longer part of the British Empire.

Contents

How the Declaration Was Written

First Ideas: The Composition Draft

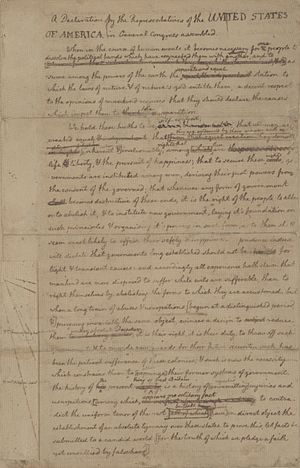

The very first known draft of the Declaration of Independence is a small piece of paper called the "Composition Draft." Thomas Jefferson, who was the main writer of the Declaration, wrote it in July 1776.

A historian named Julian P. Boyd found this draft in 1947. He was looking through Jefferson's old papers at the Library of Congress. This discovery was exciting because it showed that Jefferson had written more than one draft.

Many words from this first draft were later changed or removed by Congress. Some phrases that did stay in the final Declaration include "acquiesce in the necessity, which denounces our separation" and "hold them, as we hold the rest of mankind, Enemies in War, in Peace Friends."

Scientists have studied the paper of this draft. They found that it came from the same paper maker as the next draft, called the Rough Draft. Today, this important fragment is kept very carefully in a special cold storage vault. When it is shown, it's in a display case that controls temperature and humidity.

Working on the Rough Draft

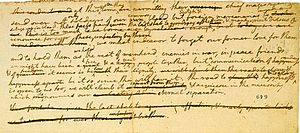

Thomas Jefferson saved a four-page draft that he later called the "original Rough draft." Historians now call it the Rough Draft. At first, people thought Jefferson wrote this draft all by himself. But now, some experts believe he wrote it after talking with a special group called the Committee of Five. We don't know how many drafts Jefferson wrote before this one. We also don't know how much other committee members helped.

Jefferson showed this Rough Draft to John Adams and Benjamin Franklin. They made a few changes. For example, Franklin might have changed Jefferson's words "We hold these truths to be sacred and undeniable" to the famous "We hold these truths to be self-evident." Jefferson added these changes to a copy that was given to Congress.

Jefferson kept his Rough Draft and wrote more notes on it as Congress made changes. He also made copies of the Rough Draft without Congress's changes. He sent these copies to friends like Richard Henry Lee and George Wythe after July 4.

The Missing Fair Copy

In 1823, Jefferson wrote a letter to James Madison. He remembered writing a "fair copy" after Franklin and Adams made their suggestions. This "fair copy" was then given to the Committee and then to Congress.

If Jefferson was right, this clean copy was given to Congress on June 28. But this document has never been found. Historian Ted Widmer said that if this paper still exists, "it is the holy grail of American freedom."

This Fair Copy was probably marked up by Charles Thomson, the secretary of the Continental Congress. Congress debated and changed the words on it. This was the document that Congress approved on July 4. It was the first "official" copy of the Declaration.

The Fair Copy was then sent to John Dunlap to be printed. It was titled "A Declaration by the Representatives of the united states of america, in General Congress assembled." Some think this Fair Copy might have been destroyed during the printing process. Or it might have been destroyed during the debates to keep things secret.

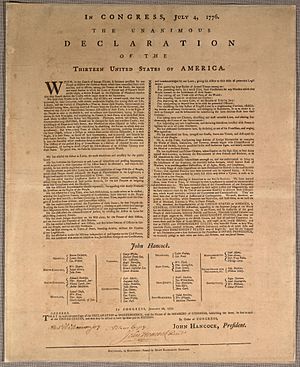

First Printed Copies: Broadsides

The Declaration was first printed as a broadside. A broadside is a large sheet of paper printed on one side. John Dunlap of Philadelphia printed these first copies. One of these broadsides was glued into Congress's official journal. This made it the "second official version" of the Declaration. Dunlap's broadsides were sent all over the thirteen states. Many states then printed their own versions.

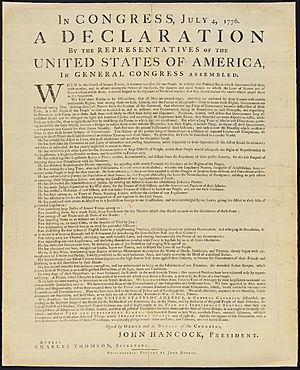

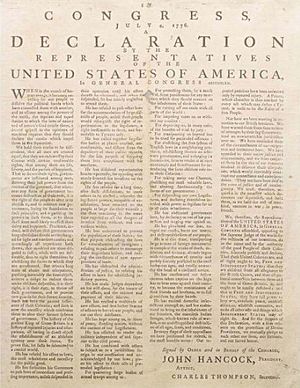

The Dunlap Broadsides

The Dunlap broadsides are the very first printed copies of the Declaration of Independence. They were printed on the night of July 4, 1776. We don't know exactly how many were printed, but it was probably around 200. John Hancock's famous signature is not on these first printed copies. But his name appears in large letters under "Signed by Order and in Behalf of the Congress." Secretary Charles Thomson is listed as a witness.

On July 4, 1776, Congress told the same committee that wrote the Declaration to "superintend and correct the press." This meant they had to watch over the printing. Dunlap, who was 29, did the job. He likely spent most of the night of July 4 setting up the type and printing the sheets.

Historians say the printing was done very quickly and with excitement. Some copies look like they were folded before the ink dried. Bits of punctuation move around from one copy to another. It's nice to imagine that Benjamin Franklin, a great printer, was there. And that Jefferson, the nervous writer, was also nearby. John Adams later wrote, "We were all in haste."

The Dunlap broadsides were sent across the new United States in the next two days. One copy went to George Washington, who was the Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army. He ordered that the Declaration be read to the troops on July 9. Another copy was sent to England.

In 1949, only 14 Dunlap broadsides were known to exist. By 1975, there were 21. In 1989, there were 24 known copies. Then, a 25th broadside was found behind a painting bought for four dollars at a flea market. On July 2, 2009, a 26th Dunlap broadside was found in The National Archives in England. No one knows for sure how it got there. It might have been taken from an American ship during the War of Independence.

Where Dunlap Broadsides Are Today

The Goddard Broadside

In January 1777, Congress asked Mary Katharine Goddard to print a new broadside. This one was different from the Dunlap broadside. It listed the names of everyone who signed the Declaration. This was the first time the public learned who had signed it. One signer, Thomas McKean, is not on the Goddard broadside. This suggests he hadn't added his name to the signed document yet.

In 1949, nine Goddard broadsides were known to still exist. They were located in places like the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., and the New York Public Library.

Other Printed Copies

Besides the broadsides Congress ordered, many states and private printers also made copies. They used the Dunlap broadside as their guide. In 1949, a study found 19 different versions of these broadsides. About 71 copies of these various editions were found.

More copies have been found since then. In 1971, a rare four-column broadside was found at Georgetown University's Lauinger Library. It was probably printed in Salem, Massachusetts. In 2010, news reports said a copy of the Declaration was found in Shimla, India. It was discovered in the 1990s in a book from the Viceroy's library.

The Official Signed Copies

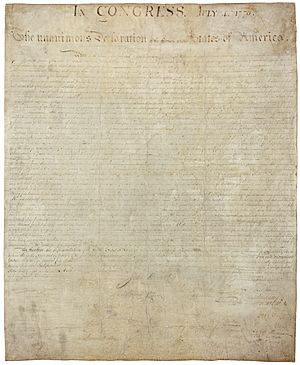

The Matlack Declaration

The copy of the Declaration that was actually signed by Congress is called the engrossed copy. It's also known as the parchment copy. This copy was probably written by hand by a clerk named Timothy Matlack. It was given the title "The unanimous declaration of the thirteen United States of America." Congress ordered this on July 19, 1776, saying it should be "fairly engrossed on parchment" and signed by every member.

During the Revolutionary War, this signed copy moved around with the Continental Congress. They moved several times to avoid the British army. In 1789, after the U.S. Constitution created a new government, the engrossed Declaration was given to the care of the secretary of state. The document was even moved to Virginia when the British attacked Washington, D.C. during the War of 1812.

After the War of 1812, the Declaration became more and more important. But the ink on the engrossed copy was fading a lot. In 1820, Secretary of State John Quincy Adams asked a printer named William J. Stone to make an engraving. This engraving was almost exactly like the original signed copy. Stone made his engraving by carefully transferring some of the original ink onto a copper plate. Then, copies could be printed from this plate.

When Stone finished his engraving in 1823, Congress ordered 200 copies to be printed on parchment. Because the original signed copy was not kept well in the 1800s, Stone's engraving is now the basis for most modern copies. As of 2021, 48 of Stone's copies still exist. One was sold at an auction for $4.42 million in 2021.

From 1841 to 1876, the engrossed copy was shown to the public. It was on a wall opposite a large window in the Patent Office building in Washington, D.C. Being exposed to sunlight and changing temperatures made the document fade very badly. In 1876, it was sent to Independence Hall in Philadelphia for an exhibit. This was for the Declaration's 100th birthday. It returned to Washington the next year.

By 1892, the document was in such poor condition that plans to show it at an exhibit in Chicago were canceled. It was then removed from public display. The document was sealed between two pieces of glass and put away. For almost 30 years, it was only shown rarely.

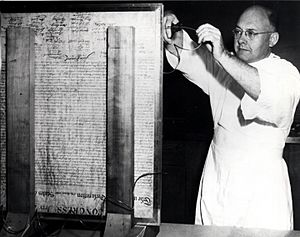

In 1921, the Declaration and the U.S. Constitution were moved from the State Department to the Library of Congress. Money was set aside to keep them safe in a public exhibit that opened in 1924. After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, the documents were moved for safety to Fort Knox in Kentucky. They stayed there until 1944.

For many years, people at the National Archives felt they should have the Declaration and Constitution. The transfer finally happened in 1952. Now, these documents, along with the Bill of Rights, are always on display at the National Archives. They are in the "Rotunda for the Charters of Freedom."

Even though they are kept in special cases filled with helium, the documents were still at risk of getting worse in the early 1980s. In 2001, experts used the newest technology to treat the documents. They moved them into new cases made of titanium and aluminum. These cases are filled with a safe argon gas. They were put back on display when the National Archives Rotunda reopened in 2003.

The Sussex Declaration

On April 21, 2017, a second parchment copy of the Declaration was found. It was discovered at the West Sussex Record Office in England. This copy is called the "Sussex Declaration." It's different from the copy at the National Archives (the Matlack Declaration). On the Sussex Declaration, the signatures are not grouped by states.

We don't know yet how this copy ended up in England. But experts think the random order of signatures might mean it came from James Wilson. He was a signer who strongly believed the Declaration was made by all the people, not just by the states. The Sussex Declaration was probably brought to England by Charles Lennox, 3rd Duke of Richmond. He was known as the 'radical duke'.

Experts believe the Sussex Declaration is a copy of the Matlack Declaration. It was probably made between 1783 and 1790. It might have been made in New York City or Philadelphia.

See also

- The Pennsylvania Evening Post, the first newspaper to print the Declaration, on July 6, 1776

- Syng inkstand, used by the delegates to sign the Declaration

- Printing of the United States Constitution

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |