Cotton Mather facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

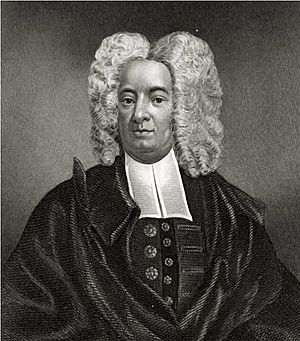

Cotton Mather

|

|

|---|---|

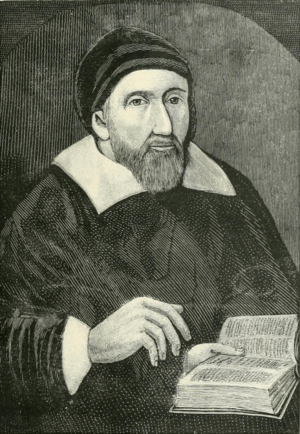

Mather, c. 1700

|

|

| Born | February 12, 1663 |

| Died | February 13, 1728 (aged 65) Boston, Province of Massachusetts Bay

|

| Resting place | Copp's Hill Burying Ground, Boston |

| Education | Harvard College (AB, 1678; MA, 1681) |

| Occupation | Minister, writer |

| Parent(s) | Increase Mather and Maria Cotton |

| Relatives | John Cotton (maternal grandfather) Richard Mather (paternal grandfather) |

| Signature | |

Cotton Mather was an important Puritan minister and writer in New England. He was born in 1663 and lived until 1728. He studied at Harvard College. In 1685, he became a minister at the Old North Meeting House in Boston, just like his father, Increase Mather. He preached there for the rest of his life.

Cotton Mather was a well-known public figure in colonial America. He helped lead a successful uprising in 1689 against Governor Edmund Andros. Mather was also involved in the Salem Witch Trials of 1692–1693. He wrote a book called Wonders of the Invisible World defending the trials. This caused a lot of debate and has affected how people view him today. He also wrote a famous history book about New England called Magnalia Christi Americana.

Mather was very interested in new scientific ideas. He studied how plants grow and how to prevent smallpox using a method called inoculation. He sent many reports to the Royal Society of London, which is a group for scientists. They made him a member in 1713. His support for smallpox inoculation caused a big argument in Boston in 1721. He learned about this method from an African man named Onesimus.

Contents

- Early Life and Education

- Revolt Against Governor Andros

- Salem Witch Trials

- Historical and Theological Writings

- Conflict with Governor Dudley

- Harvard and Yale

- Smallpox Inoculation

- Other Scientific Work

- Slavery and Racial Attitudes

- Sermons Against Pirates

- Death and Burial

- Works

- Images for kids

- See also

Early Life and Education

Cotton Mather was born in 1663 in Boston. His parents were Reverend Increase Mather and Maria Cotton. His grandfathers, Richard Mather and John Cotton, were also famous Puritan ministers. They helped start and grow the Massachusetts colony. His family was very influential and smart. It seemed like Cotton would also become a minister.

Cotton started at Harvard College in 1674 when he was only eleven years old. He was the youngest student ever admitted there. Around this time, he started to stutter. He worried this would stop him from being a preacher. He even thought about becoming a doctor instead. But Cotton returned to Harvard. He earned his first degree in 1678 and a master's degree in 1681.

After finishing school, Cotton became an assistant pastor at his father's church. In 1685, he became a full co-pastor. He and his father worked together until Increase died in 1723. Cotton Mather wrote almost 400 books and pamphlets.

Cotton Mather married Abigail Phillips in 1686. She was sixteen years old. In 1702, Abigail and two of their young children died from a measles outbreak.

Revolt Against Governor Andros

On May 14, 1686, King James II of England changed how Massachusetts was governed. He wanted to control the colony more. He appointed Sir Edmund Andros as governor. This upset the Puritans and took away some of their local control. The colonists were very angry when Andros said their land grants were no longer valid. They had to pay for new permits for land they already owned.

In April 1687, Cotton's father, Increase Mather, went to London. He stayed for four years to argue for Massachusetts's rights. In 1688, King James had a son, which meant a Catholic family might rule England. This led to the Glorious Revolution in England. Parliament removed James and gave the crown to his Protestant daughter Mary and her husband, William of Orange.

News of these events made the people in Boston brave enough to act. On April 18, 1689, the people of Boston rose up against Governor Andros. Cotton Mather, who was 26, helped guide this resistance. He might have written a document explaining why they were rebelling. He probably read this document to a crowd in Boston.

Andros and other officials were arrested and sent to London. In 1691, King William and Queen Mary issued a new charter for Massachusetts. This charter joined the Massachusetts Bay Colony with Plymouth Colony. It also said that all non-Catholics could practice their religion freely. The new government would be led by a governor chosen by the King. The first governor under this new charter was Sir William Phips, who was a member of the Mathers' church.

Salem Witch Trials

Mather's Early Involvement

In 1689, Mather wrote Memorable Providences. This book described strange events happening to children in the Goodwin family in Boston. Mather was involved in the case against a woman named Ann Glover, who was accused of witchcraft. She was found guilty and executed. Mather believed that witches and devils were real. He warned people against using magic.

Advice to the Court

In 1692, the Salem Witch Trials began. Cotton Mather said he was very involved in guiding what happened in Salem. Governor William Phips created a special court called the Court of Oyer and Terminer. His lieutenant governor, William Stoughton, became the chief judge. Mather had helped Stoughton get this important job.

Before the court's first meeting, Mather wrote a long essay for the judges. He suggested looking for "witch-marks" on people's bodies. Mather did not attend the court sessions himself, but some people said he was at the executions. He wrote about the trials, saying that justice was being done. He called one accused woman, Martha Carrier, a "rampant hag."

Spectral Evidence

During the trials, some girls claimed that invisible forms of the accused people were tormenting them. This was called "spectral evidence." It was a big debate whether this should be allowed as proof. The court decided to allow it. Mather supported using spectral evidence, but he also warned that devils could pretend to be innocent people. He believed God would usually show the truth quickly.

Ministers' Opinion

Ministers in the area were asked for their opinion on the trials. Cotton Mather helped write their response, called "Return of the Several Ministers." This document was confusing. It seemed to both allow and caution against spectral evidence. Some people thought it encouraged the trials to continue.

On August 19, 1692, Mather was present at the execution of George Burroughs and four others. He seemed to play a direct role. On September 2, 1692, after eleven people had been executed, Cotton Mather wrote a letter to Chief Justice Stoughton. He congratulated Stoughton on stopping "devilism" and said he had done a lot to help.

Later, Governor Phips stopped allowing spectral evidence in trials. This led to a sharp drop in convictions. Phips also stopped any more executions.

After the Trials

After the trials, Cotton Mather continued to defend them. He seemed to hope they might return. His book Wonders of the Invisible World defended the use of spectral evidence.

A Boston merchant named Robert Calef wrote a book called More Wonders of the Invisible World. Calef's book criticized the Mathers. He wanted to prevent new witch trials. Calef's book included apologies from some jury members and a judge. Increase Mather reportedly burned Calef's book at Harvard.

Historical and Theological Writings

Cotton Mather wrote a lot, publishing 388 different books and pamphlets. His most famous work was Magnalia Christi Americana, published in 1702. This book was a history of New England from 1620 to 1698. It included biographies of important New Englanders.

Mather also started a huge project called Biblia Americana. This was a commentary on the Christian Bible. He wanted to include new scientific knowledge in his understanding of the Bible. He wrote about geography, the idea that the Earth goes around the sun, and Newtonianism. Mather wanted to show how science and religion could work together. He could not find a publisher for this work during his lifetime.

Conflict with Governor Dudley

In the early 1700s, Joseph Dudley became governor of Massachusetts. He had been involved with the unpopular Governor Andros earlier. The Mathers did not like Dudley. But they eventually supported him as governor.

However, Governor Dudley did not keep his promises to the Mathers. He favored a small group of people. Cotton Mather preached and wrote against Governor Dudley. Mather accused him of being corrupt. Mather tried to get Dudley removed from power but failed. This made Mather feel more alone as society moved away from Puritan traditions.

Harvard and Yale

Cotton Mather was involved with Harvard College for many years. His father, Increase, had been president of Harvard. Cotton wanted to be president too. But in 1708, the college chose John Leverett the Younger instead. The Mathers thought Harvard was becoming too independent and liberal.

Cotton Mather then supported the Collegiate School, which later became Yale College. He saw it as a better place to keep Puritan beliefs strong. In 1718, Mather convinced a businessman named Elihu Yale to donate money to the school. Mather suggested changing the school's name to Yale College after this donation.

Mather hoped to become Harvard's president again after Leverett died in 1724. But he was passed over for the job several times.

Smallpox Inoculation

Smallpox was a very dangerous disease in colonial America. It caused many deaths. Boston had outbreaks in 1690 and 1702. People tried to stop it by keeping sick people separate.

In 1716, Onesimus, one of Mather's slaves, told him about a way to prevent smallpox. He had been inoculated as a child in Africa. This method involved putting a small amount of fluid from a sick person into a cut on a healthy person's skin. This would cause a mild infection, but then the person would be immune. Mather was very interested.

In 1721, smallpox returned to Boston. It spread quickly. Mather urged doctors to try inoculation. Dr. Zabdiel Boylston was the only one who agreed. He inoculated his son and two slaves. They all recovered. Boylston then inoculated more people. The epidemic caused 844 deaths in Boston. Boylston inoculated 287 people, and only six of them died.

The Debate Over Inoculation

Mather and Boylston's efforts caused a huge argument in Boston. Many people were angry. They thought inoculation spread the disease instead of preventing it. Some people even threw a lighted bomb into Mather's home.

Some doctors and ministers opposed inoculation. They argued it was against natural law and even against God's will. They believed smallpox was a punishment from God. They also thought ministers should not get involved in medicine.

Mather strongly defended inoculation. He argued it was not against God's will. He said God had given them a way to save themselves. He pointed out that very few people who were inoculated died, even when the disease was very bad. Other Puritan pastors, like Benjamin Colman, also supported inoculation.

Eventually, more people accepted inoculation. They saw that it worked and saved lives. After the epidemic, Boylston traveled to London. He published his results and became a member of the Royal Society. Mather had received this honor two years earlier.

Other Scientific Work

Cotton Mather was also a pioneer in other scientific areas. In 1716, he did one of the first experiments on plant hybridization using different types of corn. He also observed that flowering plants reproduce sexually. This idea later became part of how plants are classified.

Mather was elected a member of the Royal Society of London in 1713. This was a great honor. He was the eighth American colonist to join this important scientific group.

Mather was very excited about experimental science. He promoted new scientific ideas, like the idea that the Earth goes around the sun. He also wrote a medical manual called The Angel of Bethesda. This book included some early ideas about germ theory and recommended good hygiene. It was the only complete medical book written in colonial America at that time.

In his later years, Mather encouraged scientific research in America. He supported a man named Grafton Feveryear, who made the first weather observations in New England. Mather also helped Isaac Greenwood, who became the first professor of mathematics and natural philosophy at Harvard.

Slavery and Racial Attitudes

Cotton Mather owned slaves who worked in his home. Like most Christians at the time, he was not against slavery. However, he did speak out against the cruel parts of the slave trade.

In his book The Negro Christianized (1706), Mather said that slave owners should treat their slaves kindly. He believed they should teach them about Christianity. Mather thought black people and white people were "of one Blood" and would be equal in Heaven. He paid a teacher to instruct local black people in reading.

Mather believed that Christianizing slaves would make them better servants. He tried to convert Onesimus, the slave who taught him about inoculation. But Mather was not able to convert him. He eventually freed Onesimus in 1716.

Sermons Against Pirates

Mather also spent time ministering to convicted pirates. He wrote many pamphlets and sermons about piracy. He preached at the trials and executions of famous pirate captains like William Fly and William Kidd.

In his talks with pirates, Mather told them their actions were "Unreasonable and Abominable." He reminded them that their robberies and murders were terrible sins.

Death and Burial

Cotton Mather's wife and most of his children died before him. Only two of his 15 children survived him. He died the day after his 65th birthday. He was buried in Copp's Hill Burying Ground in Boston.

Works

Mather was a very active writer. He had many of his sermons printed.

- Major Works

- Memorable Providences (1689) - his first book about witchcraft.

- Wonders of the Invisible World (1692) - another major book about witchcraft.

- Pillars of Salt (1699)

- Magnalia Christi Americana (1702) - a history of New England.

- The Negro Christianized (1706)

- Bonifacius (1710)

- The Christian Philosopher (1721) - a book about science and religion.

Magnalia Christi Americana

Magnalia Christi Americana is seen as Mather's most important work. It was published in 1702. The book includes stories about important Puritan leaders and describes how New England was settled. Some people found it hard to read. But others praised it as a great effort to record the early history of America.

The Christian Philosopher

In 1721, Mather published The Christian Philosopher. This was the first book about science published in America. Mather tried to show that Newton's science and religion worked well together. He was inspired by other thinkers who explored how faith and reason could connect.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Cotton Mather para niños

In Spanish: Cotton Mather para niños

- John Ratcliff

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |