Edmund Andros facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Edmund Andros

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| 4th Colonial Governor of New York | |

| In office 9 February 1674 – 18 April 1683 |

|

| Monarch | Charles II |

| Preceded by | Anthony Colve |

| Succeeded by | Thomas Dongan |

| Bailiff of Guernsey | |

| In office 1674–1713 |

|

| Preceded by | Amias Andros |

| Succeeded by | Jean de Sausmarez |

| Governor of the Dominion of New England (Governor-in-chief of New England) |

|

| In office 20 December 1686 – 18 April 1689 |

|

| Preceded by | Joseph Dudley |

| Succeeded by | none (dominion dissolved) (partly Simon Bradstreet as Governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony |

| Colonial Governor of Virginia | |

| In office September 1692 – May 1698 |

|

| Preceded by | Lord Effingham |

| Succeeded by | Francis Nicholson |

| 3rd and 5th Royal Governor of Maryland | |

| In office September 1693 – May 1694 |

|

| Preceded by | Sir Thomas Lawrence |

| Succeeded by | Nicholas Greenberry |

| In office 1694–1694 |

|

| Preceded by | Nicholas Greenberry |

| Succeeded by | Sir Thomas Lawrence |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 6 December 1637 London, England |

| Died | 24 February 1714 (aged 76) London, England, Great Britain |

| Resting place | St Anne's Church, Soho, London, England |

| Signature |  |

Sir Edmund Andros (born December 6, 1637 – died February 24, 1714) was an important English leader in early British America. He served as governor of the Dominion of New England for most of its three-year existence. He also governed the colonies of New York, East and West Jersey, Virginia, and Maryland.

Before coming to North America, he was a leader in Guernsey, an island near France. His time as governor in New England was sometimes difficult. This was because he supported the Church of England, while many settlers in New England were Puritans. His actions in New England led to his removal from power during the 1689 Boston revolt. Three years later, he became the governor of Virginia.

Andros was seen as a more effective governor in New York and Virginia. He made some enemies in these colonies, but he also helped create peace treaties with the Iroquois people. These treaties, known as the Covenant Chain, brought long-lasting peace between the colonies and Native American tribes. Andros usually followed the King's orders and was praised by the rulers who appointed him.

He returned to England from Virginia in 1698. He then became the Bailiff of Guernsey again. He died in 1714.

Contents

Early Life and Military Service

Andros was born in London, England, on December 6, 1637. His father, Amice Andros, was a leader in Guernsey and a strong supporter of King Charles I. His mother, Elizabeth Stone, had a sister who worked for Elizabeth of Bohemia, the King's sister.

It's thought that Andros might have been at Castle Cornet in Guernsey when it surrendered in 1651. This was the last place to surrender to the King's enemies during the English Civil War. In 1656, he began training with his uncle, Sir Robert Stone, who was a cavalry captain. Andros then served in the army during two winter wars in Denmark. He helped defend Copenhagen in 1659. Because of these experiences, he learned to speak French, Swedish, and Dutch very well.

He remained loyal to the royal family, the Stuarts, even when they were forced to leave England. When Charles II became King again, he praised the Andros family for their support.

Andros worked for Elizabeth of Bohemia from 1660 until she died in 1662. In the 1660s, he fought in the English army against the Dutch. He later became a major in a regiment sent to Barbados in 1666. He returned to England two years later.

In 1671, he married Mary Craven. She was related to the Earl of Craven, who was a close advisor to the Queen and a friend who helped Andros for many years. In 1672, Andros was made a major.

Governor of New York

After his father passed away in 1674, Andros became the Bailiff of Guernsey. He was also chosen by James, Duke of York, to be the first governor of the Province of New York. This area included what is now New Jersey, Dutch lands along the Hudson River from New York City to Albany, and Long Island. It also included Martha's Vineyard and Nantucket.

Andros arrived in New York in October 1674. He worked with the Dutch governor to take control of the lands on November 10, 1674. Andros promised that people could keep their land and that Dutch settlers could continue to practice their Protestant religion.

Land Disputes with Connecticut

Andros also had disagreements about land borders with the nearby Connecticut Colony. The Dutch had once claimed land as far east as the Connecticut River. But these claims were changed in 1650, moving the border 20 miles (32 km) east of the Hudson River. Andros did not accept these changes. In 1675, he told Connecticut leaders that he planned to take back land that included Hartford, Connecticut, Connecticut's capital.

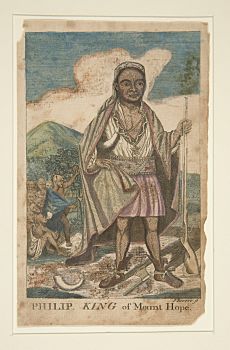

Connecticut leaders explained the border changes, but Andros argued that his new grant from the Duke of York canceled those changes. In July 1675, King Philip's War started, which was a conflict with Native Americans. Andros used this as a reason to sail to Connecticut with a small group of soldiers. He wanted to claim the land for the Duke. When he arrived at Saybrook on July 8, he saw that Connecticut soldiers were already holding the fort there. Andros went ashore, spoke briefly with the fort commander, and then returned to New York City. This was the only time Andros tried to take the land by force. However, Connecticut leaders remembered this event later on.

King Philip's War and Native American Relations

After his trip to Connecticut, Andros traveled to the land of the Iroquois people to build relationships. He was welcomed and agreed to continue the Dutch practice of giving firearms to the Iroquois. This helped stop French efforts to make alliances with the Iroquois. Some people in New England accused Andros of giving weapons to Native Americans who were fighting against them. But Andros actually provided gunpowder to Rhode Island to fight the Narragansetts. He also banned selling weapons to tribes known to be allied with King Philip. Andros's actions were approved in London, but they made relations difficult between him and the leaders in Massachusetts.

During his meeting with the Iroquois, Andros was given the name "Corlaer." This name was historically used by the Iroquois for the Dutch governor of New Netherland. It continued to be used for the English governor of New York. Another result of this meeting was the creation of a colonial department for Native American affairs in Albany. Robert Livingston became its first leader.

King Philip was known to be in western Massachusetts that winter. New Englanders accused Andros of hiding him. Andros offered to send New York troops to Massachusetts to attack Philip. But this offer was refused because New Englanders thought it was a trick for Andros to claim more land. Instead, Mohawks from the Albany area fought Philip, pushing him eastward. When Connecticut leaders later asked Andros for help, he refused, saying it was "strange" that they would ask after their earlier behavior.

In July 1676, Andros created a safe place for the Mahicans and other Native American refugees at Schaghticoke. The war ended in southern New England in 1676. However, there were still problems between the Abenaki people in northern New England and the English settlers. This led Andros to send soldiers to Maine, where they built a fort at Pemaquid (now Bristol, Maine). Andros also angered Massachusetts fishermen by limiting their use of the Duke's land for drying fish.

In November 1677, Andros went to England for about a year. While there, he was knighted for his good work as governor. He also attended meetings where he talked about the state of his colony.

Southern Border Disputes

The southern lands of the Duke of York, which included northern Delaware, were also wanted by Charles Calvert, Baron Baltimore. He wanted to expand his colony of Maryland into this area. At the same time, Calvert was trying to end a war with the Iroquois to the north. The Lenape people, who lived in Delaware Bay, were also unhappy because settlers from Virginia and Maryland were taking their lands. War was about to break out in 1673 when the Dutch took back New York.

When Andros became governor of New York, he worked to calm the situation. He became friends with the Lenape chiefs. He convinced them to help make peace between the English and other tribes. Peace seemed close, but then Bacon's Rebellion started in Virginia. This led to an attack on a Susquehannock fort. The surviving Susquehannocks moved east toward Delaware Bay. In June 1676, Andros offered to protect them if they moved into his territory. He also offered them a place to settle among the Mohawks. These offers were well received.

Maryland leaders could not convince their Native American allies to make peace. They sent surveyors to map out land also claimed by New York on Delaware Bay. Andros refused a bribe from Maryland to give up his claim to the land. Instead, he helped arrange peace talks in Albany in the summer of 1677. This peace agreement is considered one of the beginnings of the Covenant Chain alliances and treaties.

Andros could not stop Baltimore from granting some land on the Delaware. But he did prevent Maryland from taking an even larger portion of land. The Duke of York later gave these lands to William Penn, and they became part of the state of Delaware.

Controlling the Jerseys

Governing the areas known as the Jerseys also caused problems for Andros. The Duke of York had given the land west of the Hudson River to John Berkeley and George Carteret. Berkeley then sold the western part, which became West Jersey, to a group of Quakers. However, the exact rights given to Berkeley and Carteret were unclear.

This led to conflict when Andros tried to govern East Jersey. This area was managed by Philip Carteret, a cousin of George Carteret. Andros began to claim New York's authority over East Jersey after George Carteret died in 1680. Even though Andros and Governor Carteret were personally friendly, Andros eventually had Carteret arrested. In 1680, Andros sent soldiers to Philip Carteret's home in Elizabethtown. This was part of a dispute over collecting taxes on goods in Jersey ports. Carteret said he was beaten by the soldiers and jailed in New York.

Andros oversaw Carteret's trial, but a jury found Carteret innocent of all charges. Carteret returned to New Jersey, but his health was affected by the arrest, and he died in 1682. After this event, the Duke of York gave up his claims to East Jersey to the Carteret family. In 1683, Andros bought the rights to Alderney island from Carteret's widow.

A less serious disagreement happened when settlers sent by William Penn tried to establish what is now Burlington, New Jersey. Andros insisted they needed the Duke's permission. But he allowed them to settle after they agreed to follow the New York governor's rules. This situation was finally resolved in 1680 when the Duke of York gave up his remaining claims to West Jersey to William Penn.

Dominion of New England

In 1686, Andros was made governor of the Dominion of New England. He arrived in Boston on December 20, 1686, and immediately took control. His job was to govern with a council. This council included people from each colony that joined the Dominion. However, because travel was difficult and expensive, the council meetings were mostly attended by people from Massachusetts and Plymouth. The King's advisors had told Andros to govern without an assembly, which he had worried about.

The Dominion first included Massachusetts Bay Colony (which had Maine), Plymouth Colony, Rhode Island, Connecticut, and New Hampshire. In 1688, New York and the Jerseys were added. Andros's wife, who had joined him in Boston, died there in 1688.

Church of England Services

Soon after he arrived, Andros asked the Puritan churches in Boston if the Church of England could use their buildings for services. When they said no, he demanded and was given the keys to a church in 1687. Services were held there until 1688, when King's Chapel was built. These actions made local Puritans see him as favoring the Church of England. They later accused him of being involved in a "Popish plot," meaning a Catholic plot.

New Tax Laws

His council worked to make the Dominion's laws similar to English laws. This took a lot of time. In March 1687, Andros announced that old laws would stay in place until new ones were made. Since Massachusetts had no old tax laws, a new tax system was created for the whole Dominion. This new system was based on taxes that had been unpopular in Massachusetts before. Farmers felt the taxes on their animals were too high.

Many communities in Massachusetts strongly resisted the new tax laws. Some towns refused to choose people to assess their property. Officials from several towns were arrested and brought to Boston. Some were fined, while others were jailed until they agreed to do their duties. The leaders of Ipswich, who spoke out the most against the law, were tried and found guilty of minor offenses.

Other colonies did not resist the new law, even though the taxes were higher in Rhode Island than before. Plymouth's poorer landowners were hit hard by the high taxes on animals. Money from whaling, which used to go to towns, now went to the Dominion government.

Town Meeting Rules

Because of the tax protests, Andros tried to limit town meetings. He introduced a law that allowed only one meeting per year, just to elect officials. It specifically banned meetings at other times for any reason. People widely hated this loss of local power. Many protested that the town meeting and tax laws went against the Magna Carta. This document guaranteed that people would be taxed by their representatives.

Land Ownership Changes

Andros was told to make colonial land ownership more like England's system. He also had to introduce "quit-rents," which were yearly payments for land, to raise money for the colony. Land titles in Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Maine often had problems. Most of them also did not include a quit-rent payment. Land grants in Connecticut and Rhode Island were made before these colonies had official charters. This led to conflicting claims in some areas.

Andros's way of handling this was very unpopular. It threatened any landowner whose title was unclear. Some landowners went through the process to confirm their ownership. But many refused, because they did not want to risk losing their land. They saw the process as a way for the government to take land. Many Puritans in Plymouth and Massachusetts, who owned a lot of land, were among those who refused. Since all existing land titles in Massachusetts were granted under the old colonial charter, Andros declared them invalid. He required landowners to re-certify their ownership, pay fees, and start paying a quit-rent.

Andros tried to force people to confirm their ownership. But large landowners who owned many pieces of land fought these demands one by one, instead of re-certifying all their lands.

Connecticut Charter Dispute

Andros's job included Connecticut. So, he asked Connecticut Governor Robert Treat to give up the colony's charter soon after arriving in Boston. Rhode Island officials quickly agreed to join the Dominion. But Connecticut officials formally recognized Andros's authority, but did little to help him. They continued to run their government according to the charter. They held legislative meetings and elected officials while Treat and Andros discussed the charter.

In October 1687, Andros decided to travel to Connecticut himself to deal with the matter. He arrived in Hartford on October 31 with an honor guard. That evening, he met with the colonial leaders. According to a famous story, the charter was placed on the table for everyone to see during this meeting. Suddenly, the lights in the room went out. When they were relit, the charter was gone. The story says the charter was hidden in a nearby oak tree, which became known as the Charter Oak. This was done so that a search of nearby buildings would not find the document.

Whatever the truth of the story, Connecticut records show that its government formally gave up its seals and stopped operating that day. Andros then traveled through the colony, making new appointments for judges and other officials. He then returned to Boston. On December 29, 1687, the Dominion council officially extended its laws over Connecticut. This completed the joining of the New England colonies.

Adding New York and the Jerseys

On May 7, 1688, the colonies of New York, East Jersey, and West Jersey were added to the Dominion. Because these areas were far from Boston, where Andros lived, New York and the Jerseys were managed by Lieutenant Governor Francis Nicholson from New York City. Nicholson, an army captain, had come to Boston in early 1687 as part of Andros's honor guard. He had been promoted to Andros's council.

During the summer of 1688, Andros traveled to New York and then to the Jerseys to establish his authority. Governing the Jerseys was complicated. The original owners, whose charters had been taken away, still owned their land. They asked Andros for their traditional land rights. The Dominion period in the Jerseys was fairly quiet because they were far from the main power centers. The Dominion ended unexpectedly in 1689.

Native American Diplomacy

In 1687, the governor of New France, the Marquis de Denonville, attacked Seneca villages in western New York. His goal was to stop trade between the English in Albany and the Iroquois confederation, which the Seneca belonged to. He also wanted to break the Covenant Chain, a peace agreement Andros had made in 1677. New York Governor Thomas Dongan asked for help. King James ordered Andros to assist. King James also talked with Louis XIV of France, which helped ease tensions on the border.

However, on New England's northeastern border, the Abenaki people had complaints against New England settlers. They began attacking in early 1688. Andros led an expedition into Maine early that year. He raided several Native American settlements. He also raided the trading post of Jean-Vincent d'Abbadie de Saint-Castin. Andros carefully protected Castin's Catholic chapel. This later led to accusations of "popery" (being too Catholic) against Andros.

When Andros took over New York in August 1688, he met with the Iroquois in Albany to renew their agreement. In this meeting, he upset the Iroquois by calling them "children," which meant they were under English rule. The Iroquois preferred to be called "brethren," which meant they were equal. Andros returned to Boston as more Abenaki attacks happened on the New England border. The Abenaki admitted they were encouraged by the French.

While Andros was in New York, the situation in Maine had worsened. Groups of colonists raided Native American villages and took prisoners. These actions were taken based on orders from Dominion council members in Boston. They told frontier militia commanders to arrest any Abenaki suspected of being involved in raids. This caused a problem in Maine when twenty Abenaki, including women and children, were taken by colonial militia. The local authorities had to house the captives. They were sent to Falmouth and then to Boston. This angered other Native Americans in the area, who took English hostages to ensure the safe return of the captives. Andros criticized the Mainers for their actions. He ordered the Native Americans to be released and returned to Maine. A small fight during the exchange of captives led to the deaths of four English hostages. This caused more unhappiness in Maine. Facing this trouble, Andros returned to Maine with a large force. He began building more forts to protect the settlers. Andros spent the winter in Maine. He returned to Boston in March after hearing rumors of a revolution in England and unhappiness in Boston.

The Revolt in Boston

On April 18, 1689, news reached Boston that James II of England had been overthrown in England. The colonists of Boston then rebelled against Andros's rule. A well-organized crowd gathered in the city. They arrested Dominion officials and members of the Church of England. Andros and other officials took shelter in Fort Mary, a military building in the city. The old Massachusetts colonial leaders, who were back in power because of the rebellion, asked Governor Andros to surrender for his own safety. They claimed they knew nothing about the crowd. He refused and tried to escape to the Rose, the only Royal Navy ship nearby. However, the boat sent from the Rose was stopped by the militia. Andros was forced back into Fort Mary.

Negotiations took place, and Andros agreed to leave the fort to meet with the rebel council. He was promised safe passage. But he was marched under guard to the building where the council had met. There, he was told that "they must & would have the Government in their own hands," and that he was under arrest. Daniel Fisher grabbed him and took him to the home of official John Usher. He was held there under close watch.

After Fort Mary fell to the rebels on April 19, Andros was moved there from Usher's house. He was held there with Joseph Dudley and other Dominion officials until June 7. Then, he was moved to Castle Island. It is said that during this time, he tried to escape by dressing in women's clothing. This story was widely told, but the Anglican minister Robert Ratcliff said it was not true. He claimed the story and others were "falsehoods, and lies" spread to make the Governor look bad.

Andros did successfully escape from Castle Island on August 2. His servant gave the guards drinks. He managed to flee to Rhode Island. But he was quickly caught again and kept mostly alone. He and others were held for 10 months before being sent to England for trial. The Massachusetts representatives in London refused to sign the charges against him. So, the court quickly dismissed them, and Andros was set free. When Andros was asked about the accusations, he said that all his actions were meant to make colonial laws match English law. Or, they were specifically done as part of his job and instructions.

While Andros was held captive, the New York government was also overthrown. This happened during an event called Leisler's Rebellion. Andros was eventually allowed to leave for England. By that time, the Dominion of New England had ended. The colonies went back to their old ways of governing. Massachusetts was reorganized into the Province of Massachusetts Bay in 1691.

Governor of Virginia

Andros was welcomed at court when he returned to England. The new king, William III, remembered that Andros had visited his court in the Netherlands. He approved of Andros's service. Andros offered to work as a spy, suggesting he go to Paris to meet with the exiled King James. His real goal would be to try to get French military plans. This idea was rejected. While in England, he married for the second time to Elizabeth Crisp Clapham in July 1691.

Andros's next job opportunity came when Lord Effingham resigned as governor of the Province of Virginia in February 1692. Francis Nicholson, who had been a lieutenant governor in the Dominion, wanted the top position in Virginia. But King William gave the governorship to Andros. Nicholson was given another lieutenant governorship, this time in Maryland. This made Andros's time as governor more difficult because his relationship with Nicholson had become bad. The exact reasons for their dislike are unclear.

Andros arrived in Virginia on September 13, 1692, and started his duties a week later. Nicholson welcomed him kindly and then sailed for England. Andros settled at Middle Plantation, which later became Williamsburg. He lived there until 1695. He worked to organize the colony's records, which had been neglected since Bacon's Rebellion. He also supported laws to prevent slave rebellions.

He encouraged Virginia to grow different crops. At that time, the economy depended almost entirely on tobacco. The war happening at the time, the Nine Years' War, was hurting the economy. Merchant ships had to travel in groups with protection. For several years, Virginia did not get any military escorts, so their products could not be sold in Europe. Andros encouraged new crops like cotton and flax. He also encouraged the making of fabric.

Virginia was the first colony where Andros had to work with a local assembly. His relationship with the House of Burgesses was generally friendly. But he faced some resistance, especially regarding war measures and colonial defenses. He hired armed ships to patrol the colony's waters. He also gave money to New York's colonial defenses. These defenses protected Virginia from possible French and Native American attacks. In 1696, the King ordered Andros to send troops to New York. The Burgesses reluctantly approved £1,000 for this. Andros successfully managed colonial defense and relations with Native Americans. Unlike New York and New England, Virginia was not attacked during the war.

During his time as governor, Andros made an enemy of James Blair, a well-known Anglican minister. Blair was working to create a new college to train Anglican ministers. He believed that Andros did not support this idea. However, Blair and Nicholson worked closely on this project. The two men disliked Andros, and their actions helped cause Andros to resign. The College of William & Mary was founded in 1693. Even though Blair claimed Andros was not supportive, Andros paid for the bricks to build the college's chapel from his own money. He also convinced the House of Burgesses to approve £100 per year for the college.

Blair's complaints, which were often unclear and not entirely accurate, reached London. Investigations into Andros's actions began in 1697. Andros had lost most of his support when a new political group came to power. His supporters could not convince the board to favor him. Anglican bishops strongly supported Blair and Nicholson. In March 1698, Andros, saying he was tired and ill, asked to be recalled.

Later Years and Legacy

Andros's recall was announced in London in May 1698. Nicholson replaced him. Andros returned to England and resumed his job as bailiff of Guernsey. He split his time between Guernsey and London. His second wife died in 1703. He married for the third time in 1707 to Elizabeth Fitzherbert. In 1704, Queen Anne named him Lieutenant Governor of Guernsey, a position he held until 1708. He died in London on February 24, 1714, and was buried at St Anne's Church, Soho. His wife died in 1717 and was buried nearby. The church was destroyed during World War II, so there is no longer any trace of their graves. He did not have any children.

The historian Michael Kammen said that Andros did not succeed in his roles in the colonies. This was partly because he was not harsh enough to force people to obey him, nor friendly enough to gain their support. It was also because he came to New England at a difficult time without understanding the unique religious and political situation there. Finally, he was always caught between the King's strong demands and the unfamiliar needs of colonial life.

Andros is still a well-known figure in New England, especially in Connecticut. Connecticut does not officially include him on its list of colonial governors. However, his portrait hangs in the Hall of Governors in the State Museum across from the State Capitol in Hartford. Even though he was disliked in the colonies, he was seen in England as an effective administrator. He carried out the policies he was ordered to and advanced the King's goals. His biographer, Mary Lou Lustig, noted that he was "an accomplished statesman, a brave soldier, a polished courtier, and a devoted servant." But his style was often "autocratic, arbitrary, and dictatorial." He lacked tact and had trouble finding compromises.

Andros appears as a character in the 1879 novel Captain Nelson, which is a "romance of colonial days." He also appears in several episodes of The Witch of Blackbird Pond. In this story, his conflict with the Connecticut colonists is part of the background to the main character's personal problems. It is believed that Andros Island in the Bahamas was named after him. Early owners of the Bahamas included members of his first wife's family, the Cravens.

Images for kids

-

Sir George Carteret, who owned East Jersey.

See also

In Spanish: Edmund Andros para niños

In Spanish: Edmund Andros para niños