Leisler's Rebellion facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Leisler's Rebellion |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Glorious Revolution | |||

|

|||

| Date | May 31, 1689 – March 21, 1691 | ||

| Location | |||

| Resulted in |

|

||

| Parties to the civil conflict | |||

|

|||

| Lead figures | |||

|

|||

Leisler's Rebellion was an uprising in the late 1600s in colonial New York. A German-American merchant and militia leader named Jacob Leisler took control of the southern part of the colony. He ruled it from 1689 to 1691. This rebellion happened after England's Glorious Revolution and a similar uprising in Boston. The people of New York were unhappy with the rules set by the old King, King James II.

The King's power was not fully back until 1691. That's when English soldiers and a new governor arrived in New York. Leisler was arrested, tried, and found guilty of treason. He was then executed. The rebellion left the colony deeply divided. There were two main groups: those who supported Leisler and saw him as a hero, and those who were against him.

Contents

Why the Rebellion Started

English forces took over New Netherland in 1664. King Charles II gave this land to his brother, James, who was then the Duke of York. James ruled the area with a strong governor and council, but without an elected assembly.

In 1685, James became King James II. The next year, he created the Dominion of New England. This was a large area that included New York and other colonies. In 1688, King James added New York to the Dominion. The governor of this Dominion, Sir Edmund Andros, came to New York. He put Francis Nicholson, an army captain, in charge as his lieutenant governor.

Nicholson ruled with a local council but no elected assembly. Many New Yorkers felt he was taking away their old rights. Nicholson believed the colonists were "conquered people." He thought they could not claim the same rights as people in England.

In late 1688, the Glorious Revolution happened in England. King James II, who was Catholic, was removed from power. William III and Mary II, who were Protestant, became the new rulers. Governor Andros was very unpopular, especially in New England. His opponents in Massachusetts used this change in power to start an uprising.

On April 18, 1689, a crowd in Boston arrested Andros and other officials. This led to other events where colonies like Massachusetts quickly brought back their old governments.

Growing Problems

Lieutenant Governor Nicholson heard about the Boston uprising by April 26. He did not announce the news or the changes in England. He feared it would cause a rebellion in New York. However, leaders on Long Island learned about Boston. They became more confident, and by mid-May, officials of the Dominion were removed from several towns.

At the same time, Nicholson learned that France had declared war on England. This meant there was a danger of attacks from French and Native American groups on New York's northern border. Nicholson also had few soldiers. Most of his troops had been sent away. He found that his soldiers believed he was trying to bring Catholic rule to New York. He tried to calm the worried citizens by inviting the militia to join the army at Fort James in Manhattan.

New York's defenses were in bad shape. Nicholson's council voted to charge import taxes to fix them. This was met with strong resistance. Many merchants refused to pay the tax. One of them was Jacob Leisler. He was a German-born merchant and militia captain. Leisler strongly opposed the Dominion government. He saw it as an attempt to force Catholic rule on the colony.

On May 22, the militia asked Nicholson's council for faster improvements to the city's defenses. They also wanted access to the fort's gunpowder storage. This request was denied. This made people more worried that the city did not have enough gunpowder.

The Rebellion Begins

On May 30, 1689, Nicholson made an angry comment to a militia officer. This incident quickly turned into an open rebellion. Nicholson was known for his bad temper. He told the officer, "I rather would see the Towne on fire than to be commanded by you." Rumors spread that Nicholson was ready to burn the town. He called the officer and demanded he give up his position. Abraham de Peyster, a wealthy man and the officer's commander, argued fiercely with Nicholson. After this, de Peyster and his brother, also a militia captain, left the council meeting.

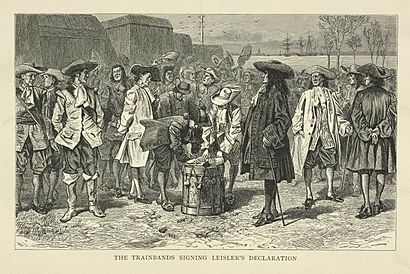

The militia was called out and marched to Fort James. They took control of the fort. An officer was sent to the council to demand the keys to the gunpowder storage. Nicholson finally gave them up to "prevent bloodshed and further mischief." The next day, a group of militia officers asked Jacob Leisler to take command of the city militia. He agreed. The rebels then announced they would hold the fort for the new King and Queen until a proper governor was sent.

Leisler's exact role in starting the militia uprising is not fully known. However, he and another captain had presented the petition on May 22. One of his officers led the militia to the fort gates. Another officer demanded the keys to the gunpowder.

Leisler Takes Charge

At this point, the militia controlled the fort and the harbor. When ships arrived, they brought people directly to the fort. This cut off Nicholson and his council from outside news. On June 6, Nicholson decided to leave for England. He started collecting statements to use there. He left the city on June 10, hoping to join Thomas Dongan, who was also going to England.

At first, Leisler's control was limited. His councilors, including Nicholas Bayard and Stephanus van Cortlandt, were still in the city. They did not accept his authority. The city's government, with van Cortlandt as mayor, also did not recognize him. A message about William and Mary was sent to Hartford, Connecticut. Both sides in New York rushed to get copies of this message. Leisler's agents got there first. Leisler published the message on June 22. Two days later, van Cortlandt received an official notice from William and Mary meant for Andros. This document had been delayed by agents in London.

This document said that all non-Catholic officials could stay in their jobs. This technically made the council's rule legal while Nicholson was away. Following this, van Cortlandt fired the customs collector, who was Catholic. He replaced him with Bayard and others to handle customs. Leisler did not like this. He went to the customs house with his militia. Both sides said there was almost a riot. Bayard claimed he barely escaped being killed. Bayard then fled to Albany, and van Cortlandt followed a few days later. Philipse left politics. This left Leisler in charge of the city.

On June 26, delegates from several towns in lower New York and East Jersey met. They formed a committee of safety to manage things. This committee became the core of Leisler's government. They chose Leisler to be the province's commander-in-chief "until orders shall come from their Majesties."

Through July and August, Leisler's chosen militia controlled the city. They used money that Nicholson had left in the fort. Officials from Connecticut helped by sending soldiers to hold the fort. Nicholson's soldiers were officially dismissed on August 1. Around the same time, news arrived that France and England were at war.

Leisler sent Jost Stoll and Matthew Clarkson to England on August 15. They were to strengthen his position with the government in London. They carried documents accusing Nicholson of working against the people of New York. They also explained why Leisler's actions against Nicholson's "unfair" rule were right. The agents were told to ask for a new charter for the colony. They were also to claim that the united colonies could defeat New France without help from England. He did not specifically ask for the new charter to include democratic representation.

In October, an election ordered Leisler's committee of safety to officially remove van Cortlandt from office. This gave Leisler full control over New York, except for the Albany area. According to Bayard, very few people voted in New York City, only about 100. Councilors Bayard and Philipse announced on October 20 that Leisler's rule was illegal. They told other militia leaders to stop supporting him. But their announcement had no effect.

Resistance in Albany

Leisler's opponents had taken control of Albany and the surrounding area. On July 1, they officially announced their support for William and Mary. On August 1, they formed a group called the Albany Convention to rule. This group included local militia leaders and wealthy landowners from the Hudson River valley. It became the center of anti-Leisler activities. The convention refused to recognize Leisler's rule unless he showed them an official order from William and Mary.

Albany's situation became tense in September. Local Native Americans brought news of a possible attack from French Canada. Leisler was stopping military supplies from going up the Hudson River. So, Albany officials had to ask him for help. He responded by sending Jacob Milborne, a close advisor, with soldiers to take military control of Albany in November.

However, the convention did not agree to Milborne's demands for his support. He was not allowed into the city or Fort Frederick. An Iroquois woman warned him that many Native Americans near Albany saw him as a threat to their friends in Albany. She said they would act if he tried to take military control. Milborne returned to New York City. The convention also asked neighboring colonies for military help. Connecticut sent 80 soldiers to Albany in late November.

Leisler finally gained control over Albany in early 1690. He called for elections in Schenectady in January 1690. This was a move to divide nearby communities. In early February, during King William's War, Schenectady was attacked by French and Native American raiders. This showed how weak the Albany Convention's position was. Each side blamed the other for failing to defend Schenectady. But Leisler was able to use the situation to his advantage. He convinced Connecticut to take back its soldiers. He then sent his own militia north to take control of the area. The convention gave up because they had no strong outside support.

Leisler's Time in Power

In December 1689, a letter arrived from William and Mary. It was addressed to Nicholson or, "in his absence to such as for the time being take care for preserving the peace and administering the laws in our said Province of New York." The letter told the recipient to "take upon you the government of the said province." The messenger tried to deliver the message to van Cortlandt and Philipse. But Leisler's militia seized him. Leisler used this document to claim his rule was legal. He began calling himself "lieutenant governor." He also created a governor's council to replace the committee of safety.

Leisler then started trying to collect taxes and customs duties. He was partly successful. But he faced a lot of resistance from officials who opposed him. Some were arrested, and most of those who refused his orders were replaced. By April 1690, Leisler had appointed officials in almost every town in New York. These officials came from different parts of New York society. They included important Dutch and English residents.

However, people continued to resist his rules. On June 6, a small crowd attacked him. They demanded the release of political prisoners and refused to pay his new taxes. In October 1690, various communities protested his rule. These included Dutch Harlem, English Queens County, and Albany.

Leisler's main activity in 1690 was organizing a military trip against New France. This idea began to form in a meeting in May with representatives from nearby colonies. To get supplies for New York's soldiers, he ordered merchants to offer their goods. If they refused, he broke into their storehouses. He kept careful records of these actions, and many merchants were later paid back. Connecticut officials did not want Jacob Milborne, Leisler's choice, to lead the soldiers. They said their own commanders had more experience. Leisler agreed to their choice of Fitz-John Winthrop.

The military trip was a complete failure. It fell apart due to sickness and problems with transportation and supplies. However, Winthrop did get some revenge for the Schenectady massacre of February 1690. He sent a small group north to raid La Prairie, Quebec. Leisler blamed Winthrop for the failure and briefly arrested him. This caused protests from Connecticut Governor Robert Treat.

What Happened Next

Leisler and Milborne's executions made them heroes to their supporters. It did nothing to heal the deep divisions between those who supported Leisler and those who opposed him. Leisler's supporters sent agents to London, later joined by his son Jacob. They asked the government for justice. In January 1692, the King heard their request. In April, the Lords of Trade suggested pardons for the six remaining prisoners. On May 13, 1692, Queen Mary told the new governor, Benjamin Fletcher, to pardon the remaining six prisoners.

Governor Sloughter's sudden death on July 23, 1691, made some people suspect he was poisoned. However, an examination showed he died of pneumonia. He left a letter saying he was "forced" by those around him to order the execution. Other things he did also caused talk. Ingoldesby, who took over after his death, accused him of taking £1,100 meant for the soldiers. He was also said to have taken a captured ship that had been sold at auction and then sold it a second time.

One of Leisler's supporters stopped in Boston on his way to England. Sir William Phips, the new governor of Massachusetts, offered support. Massachusetts agents in London then worked to have Leisler's family's property returned. A bill was introduced in Parliament in 1695 to do this. Massachusetts supporters helped. The bill quickly passed in the House of Lords. However, anti-Leislerian agents managed to send it to a committee in the lower house. It finally passed on May 2, 1695, after long hearings. In these hearings, Joseph Dudley defended his actions by saying Leisler took power wrongly because he was a foreigner. The King approved it the next day.

However, it was not until 1698 that Leisler's family finally got what they were owed. The Earl of Bellomont arrived that year. He had been made New York's governor in 1695 and was a strong supporter of Leisler in the Parliament debate. He died in office in 1701. But during his time, he put Leisler's supporters in important government jobs. He made sure the family's property was returned. He also had the bodies of Leisler and Milborne properly reburied in the yard of the Dutch Reform Church.

The groups supporting and opposing Leisler continued to argue until Governor Robert Hunter arrived in 1710. Over time, Leisler's supporters tended to side with the English Whig party. Those against Leisler sided with the English Tories. Hunter was a Whig who generally favored Leisler's supporters. But he was able to calm the strong disagreements between the groups.

Why This Rebellion Was Important

Some historians believe this rebellion was mainly a Dutch uprising against English rule. However, Leisler did not get the full support of the Dutch Reformed Church. Leisler, whose father was a German Reformed minister, used the public's dislike of Catholics. He was mainly supported by craftspeople and small traders. These people were against the power of wealthy merchants like the patroons.

Leisler's Rebellion fits a pattern with other rebellions from the same time. These include Bacon's Rebellion in 1676, the 1689 Boston revolt that removed Andros, Gove's Rebellion in New Hampshire in 1683, Culpeper's Rebellion in North Carolina in 1677, and the Protestant Rebellion in Maryland in 1689.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Rebelión de Leisler para niños

In Spanish: Rebelión de Leisler para niños

| Shirley Ann Jackson |

| Garett Morgan |

| J. Ernest Wilkins Jr. |

| Elijah McCoy |