1689 Boston revolt facts for kids

Quick facts for kids 1689 Boston revolt |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Glorious Revolution | |||||||

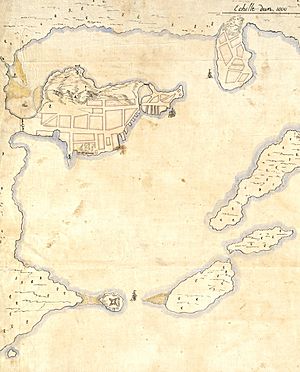

A 19th-century interpretation showing the arrest of Governor Andros during Boston's brief revolt |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Simon Bradstreet Cotton Mather |

Sir Edmund Andros (POW) John George (POW) |

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 2,000 militia many citizens |

about 25 soldiers (POW) One frigate |

||||||

The 1689 Boston revolt was a big uprising that happened on April 18, 1689. People in Boston rose up against Sir Edmund Andros. He was the governor of a large area called the Dominion of New England.

A large, organized group of local soldiers (militia) and citizens gathered in Boston. Boston was the main city of the Dominion. They arrested many officials who worked for the Dominion government. People who supported the Church of England and seemed to agree with Governor Andros were also arrested. No one was hurt or killed during this revolt. After the revolt, leaders from the old Massachusetts Bay Colony took back control of the government. In other colonies, leaders who had lost their power under the Dominion also got it back.

Andros became governor of New England in 1686. Many people in the area disliked him. He made them follow strict trade rules called the Navigation Acts. He also said that people's land ownership papers were not valid. He limited town meetings and put unpopular officers in charge of the local militia. Andros also made Puritans in Boston angry by promoting the Church of England. Many New England colonists were nonconformists and did not like this.

Contents

Why the Revolt Happened

In the early 1680s, King Charles II of England wanted to change how the colonies in New England were run. He took away the special permission (charter) of the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1684. This happened because the colony's leaders did not follow his demands. Charles wanted to make the colonies easier to control and bring them closer to the king's power.

King Charles died in 1685. His brother, James II, became king and continued these efforts. King James II was Roman Catholic. He created the Dominion of New England. He appointed Sir Edmund Andros, who used to be governor of New York, as the Dominion's governor in 1686.

The Dominion included the areas of Massachusetts Bay, Plymouth Colony, Connecticut Colony, Province of New Hampshire, and Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations. In 1688, it grew even bigger. It then included New York, East Jersey, and West Jersey.

Governor Andros was very unpopular in New England. He did not care about local opinions. He said that land ownership papers in Massachusetts were not valid. These papers depended on the old charter. He also limited town meetings. Andros forced the Church of England into areas that were mostly Puritan. He also made people follow the Navigation Acts. These laws threatened how New Englanders traded goods. The king's soldiers in Boston were often treated badly by their officers. These officers supported the governor and were often Anglican or Roman Catholic.

Meanwhile, King James II became very unpopular in England. He upset many people, even those who usually supported him. He tried to make laws that would give more freedom of religion. He issued the Declaration of Indulgence in 1687. This move was opposed by the Anglican church leaders. He also made the army stronger. Many members of Parliament saw this as a threat to their power. He also put Catholics in important army jobs.

King James tried to get people who supported him into Parliament. He hoped they would remove a law called the Test Act. This law required a strict Anglican religious test for many government jobs. Some political groups, called Whigs and Tories, put aside their differences. This happened when King James's son, James, was born in June 1688. They then planned to replace the king with his Protestant son-in-law, William, Prince of Orange. William had tried to get King James to change his policies, but it didn't work. So, William agreed to invade England. This led to a nearly bloodless revolution in November and December 1688. William and his wife Mary became the new rulers.

Religious leaders in Massachusetts, like Cotton and Increase Mather, did not like Andros's rule. They tried to influence the court in London. Increase Mather sent a letter to King James thanking him for the Declaration of Indulgence. He also told other Massachusetts pastors to do the same. This was a way to gain favor and influence. Ten pastors agreed, and Increase Mather went to England to argue against Andros.

Dominion secretary Edward Randolph tried to stop Mather many times. He even tried to bring criminal charges against him. But Mather secretly got on a ship to England in April 1688. He and other Massachusetts representatives met King James in October 1688. The king promised to help with the colony's problems. However, the revolution in England stopped these efforts.

The Massachusetts representatives then asked the new rulers, William and Mary, to bring back the Massachusetts charter. Mather also convinced the Lords of Trade (who managed colonial affairs) to delay telling Andros about the revolution. Mather had already sent a letter to the former colonial governor, Simon Bradstreet. The letter said that the old Massachusetts charter had been taken away illegally. He told the leaders to "prepare the minds of the people for a change."

Rumors about the revolution reached some people in Boston before official news arrived. A Boston merchant named John Nelson wrote about the events in a letter in late March. This letter led to a meeting of important anti-Andros leaders in Massachusetts.

Andros first heard about the coming revolt while he was strengthening a fort in Pemaquid (Bristol, Maine). He was trying to protect the area from French and Native American attacks. In early January 1689, he got a letter from King James about the Dutch army getting ready. On January 10, Andros issued a warning against Protestant unrest. He also banned any uprising against the Dominion.

The soldiers he led in Maine were British regulars and militia from Massachusetts and Maine. The militia companies were led by regular soldiers who were very strict. This made the militiamen dislike their officers. Andros heard about the meetings in Boston and also got unofficial news of the revolution. He returned to Boston in mid-March. A rumor spread that he had taken the militia to Maine as part of a "Catholic plot." The Maine militia rebelled, and those from Massachusetts started going home.

An official announcement of the revolution reached Boston in early April. Andros had the messenger arrested, but the news still spread. This made the people bolder. On April 16, Andros wrote to his commander in Pemaquid. He said "there is a general buzzing among the people, great with expectation of their old charter." He was also getting ready to arrest the soldiers who had left their posts and send them back to Maine. The threat of arrests by their own colonial militia increased tensions between the people of Boston and the Dominion government.

The Revolt in Boston

Around 5 a.m. on April 18, local militia groups started gathering outside Boston. They met in Charlestown, across the Charles River, and in Roxbury, at the end of the Boston Neck. Around 8 a.m., the Charlestown groups crossed the river in boats. The Roxbury groups marched into the city. At the same time, men from the Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company went into the homes of army drummers. They took their equipment.

The militia groups met around 8:30 a.m. A growing crowd joined them. They began arresting Dominion and army leaders. They eventually surrounded Fort Mary, where Governor Andros was staying.

One of the first people arrested was Captain John George of HMS Rose. He came ashore between 9 and 10 a.m. He was met by a group of militia and the ship's carpenter, who had joined the Americans. George asked to see an arrest warrant. The militiamen drew their swords and took him into custody. By 10 a.m., most Dominion and military officials had been arrested. Others had fled to safety at Castle Island or other forts. People in Boston who supported the Church of England were also rounded up. This included a church leader and a pharmacist.

Sometime before noon, an orange flag was raised on Beacon Hill. This signaled 1,500 more militiamen to enter the city. These troops gathered in the market square. A statement was read there. It supported "the noble Undertaking of the Prince of Orange." It called on the people to rise up because of a "horrid Popish Plot" (a rumor about a Catholic plan) that had been discovered.

The Massachusetts colonial leaders, led by former governor Simon Bradstreet, then told Governor Andros to surrender for his own safety. He refused and tried to escape to the Rose ship. But the militia stopped a boat coming from the Rose. Andros was forced back into Fort Mary.

They talked, and Andros agreed to leave the fort to meet with the council. He was promised safe passage. He marched under guard to the town hall where the council had gathered. There, he was told that "they must and would have the Government in their own hands." This is how an unknown person described it. He was then arrested. Daniel Fisher grabbed him by the collar. Andros was taken to the home of Dominion official John Usher and watched closely.

The Rose ship and Fort William on Castle Island did not surrender at first. However, on April 19, the crew on the Rose was told that the captain planned to take the ship to France. He wanted to join the exiled King James. A fight broke out, and the Protestant crew members took down the ship's sails. The soldiers on Castle Island saw this and then surrendered.

What Happened Next

Fort Mary surrendered on April 19. Andros was moved there from Usher's house. He was held with Joseph Dudley and other Dominion officials until June 7. Then he was moved to Castle Island. A story spread that he tried to escape dressed in women's clothing. But Boston's Anglican minister, Robert Ratcliff, said this story was false. He claimed it was spread to make the governor look bad.

Andros did successfully escape from Castle Island on August 2. His servant bribed the guards with alcohol. He managed to flee to Rhode Island. But he was caught soon after and kept almost completely alone. He and others arrested after the revolt were held for 10 months. Then they were sent to England for trial. Massachusetts representatives in London refused to sign the papers listing the charges against Andros. So, he was found not guilty and released. He later served as governor of Virginia and Maryland.

End of the Dominion

The other New England colonies in the Dominion learned about Andros being overthrown. Colonial leaders then worked to bring back their old governments. Rhode Island and Connecticut started governing themselves again under their old charters. Massachusetts went back to governing itself based on its old charter. For a short time, it was run by a committee of leaders and some of Andros's former council members. New Hampshire was temporarily without a formal government. It was controlled by Massachusetts and its governor, Simon Bradstreet. Plymouth Colony also went back to its old way of governing.

While he was held captive, Andros sent a message to Francis Nicholson. Nicholson was his lieutenant governor in New York. Nicholson received the request for help in mid-May. But most of his soldiers had been sent to Maine. He could not do anything helpful because tensions were also rising in New York. Nicholson himself was overthrown by a group led by Jacob Leisler. Nicholson then fled to England. Leisler governed New York until 1691. Then, soldiers arrived, followed by Henry Sloughter. Sloughter was appointed governor by William and Mary. Sloughter had Leisler tried for treason. He was found guilty and executed.

English officials did not try to bring back the Dominion after Leisler's Rebellion was stopped. They also did not try to restore the colonial governments in New England. Once Andros's arrest was known, discussions in London focused on Massachusetts and its old charter. This led to the creation of the Province of Massachusetts Bay in 1691. This new province combined Massachusetts with Plymouth Colony and areas that used to belong to New York. These included Nantucket, Martha's Vineyard, the Elizabeth Islands, and parts of Maine. Increase Mather tried to bring back the old Puritan rule, but he was not successful. The new charter said that a governor would be appointed. It also allowed for religious toleration, meaning more freedom of religion.

See also

In Spanish: Revuelta de Boston (1689) para niños

In Spanish: Revuelta de Boston (1689) para niños