Abenaki facts for kids

Flag of St. Francis/Sokoki Band of Abenaki

|

|

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| (12,000 (US and Canada)) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| United States (Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont) Canada (New Brunswick, Quebec) |

|

| Languages | |

| English, French, Abenaki | |

| Religion | |

| largely Roman Catholic | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Algonquian peoples |

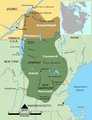

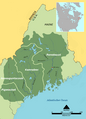

The Abenaki (also called Abnaki) are a group of Native American and First Nations people. They are part of the Algonquian-speaking peoples who live in northeastern North America. The Abenaki live in the New England area of the United States and in Quebec and the Maritimes of Canada. This region is known as Wabanaki ("Dawn Land") in their language.

The Abenaki are one of the five groups that form the Wabanaki Confederacy. The name "Abenaki" describes a group of people who share a language and live in the same area. Historically, they didn't have one strong central government. Instead, they were made up of many smaller bands and tribes who shared similar ways of life.

Contents

What does "Abenaki" mean?

The word Abenaki means “people of the dawnlands.” This name comes from their location in the eastern part of North America, where the sun rises first.

Where did the Abenaki live?

Historically, the Abenaki lived across a large area. This included parts of what are now Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont in the United States. They also lived in Quebec and the Maritimes in Canada. This land was known as Wabanaki, or "Dawn Land."

What language do the Abenaki speak?

The Abenaki language is closely related to the Panawahpskek (Penobscot) language. Other nearby Wabanaki tribes, like the Mi'kmaq, Wolastoqiyik (Maliseet), and Pestomuhkati (Passamaquoddy), have similar languages.

Sadly, the Abenaki language is almost gone as a spoken language. But tribal members are working hard to bring it back. They are teaching it at Odanak (meaning "in the village"), a First Nations Abenaki reserve near Pierreville, Quebec. Efforts are also being made in New Hampshire, Vermont, and New York state.

What is the history of the Abenaki people?

In 1614, a man named Thomas Hunt captured 24 young Abenaki people and took them to England. During the time when Europeans were settling North America, the Abenaki's land was between the new English colonies in Massachusetts and the French in Quebec. Since no one agreed on borders, there were often fights.

The Abenaki usually sided with the French. During the rule of King Louis XIV, a chief named Assacumbuit was even made a member of French nobility for his help.

Because of attacks from the English and new diseases that spread, many Abenaki started moving to Quebec around 1669. The governor of New France gave them two large areas of land. One was on the Saint Francis River, now called the Odanak Indian Reservation. The other was near Bécancour and is called the Wolinak Indian Reservation.

The English and French often attacked each other's settlements with the help of their Native American allies. Some people who were captured were adopted into the Mohawk and Abenaki tribes. Older captives were usually traded back for money or goods.

In 1724, during Father Rale's War, the English took the main Abenaki town in Maine, Norridgewock. They also killed their Catholic missionary, Father Sébastien Rale, who had encouraged the war. The next year, a group of English colonists, led by John Lovewell, fought an Abenaki group near what is now Fryeburg, Maine. Because of these pressures, more Abenaki moved to the settlement on the St. Francis River.

Many Abenaki moved further north as white settlers took over the coast and southern New England. When they later attacked the English, they were seen as invaders from Canada. But they were actually Native Americans fighting for their homeland.

How did the Abenaki in Canada develop?

Tourism has helped the Canadian Abenaki build a modern economy. This also helps them keep their culture and traditions alive. For example, since 1960, the Odanak Historical Society has run one of Quebec's largest Native American museums. Over 5,000 people visit the Abenaki Museum each year.

Several Abenaki companies are successful. In Wôlinak, General Fiberglass Engineering employs many Native people. Odanak is also active in transportation and distribution. A famous Abenaki from this area is the filmmaker Alanis Obomsawin, who works for the National Film Board of Canada.

What happened to the Abenaki in the United States?

No Abenaki group has been officially recognized by the United States government as a tribe.

Abenaki in Vermont

In 2006, the state of Vermont officially recognized the Abenaki as a People, but not a Tribe. The state noted that many Abenaki had blended into society. Only small groups remained on reservations during and after the French and Indian War. Later, unfair programs further harmed the Abenaki people in America. As mentioned, many Abenaki had started moving to Canada, which was then controlled by the French, around 1669.

The Sokoki-St. Francis Band of the Abenaki Nation formed a tribal council in 1976 in Swanton, Vermont. Vermont recognized this council that same year but later withdrew its recognition. In 1982, the band asked for federal recognition, which is still being decided.

Four Abenaki communities are in Vermont. On April 22, 2011, Vermont officially recognized two Abenaki bands: the Nulhegan Band of the Coosuk-Abenaki and the El Nu Abenaki Tribe. On May 7, 2012, the Abenaki Nation at Missisquoi and the Koasek of the Koas Abenaki Traditional Band also received recognition from the State of Vermont.

The Abenaki who stayed in the United States did not have it as easy as those in Canada. Connections to their tribes were lost as they became part of colonial society.

What was Abenaki culture like?

There are many ways to spell "Abenaki," like Abenaquiois, Abakivis, and Wabenakies.

The Abenaki tribes lived a life similar to other Algonquian-speaking peoples in southern New England. They grew crops for food and built their villages near fertile river areas. They also hunted animals, fished, and gathered wild plants for food.

For most of the year, they lived in small groups of extended families. Each man had hunting lands passed down from his father. Unlike the Iroquois, the Abenaki traced their family lines through the father's side.

In spring and summer, bands would gather at temporary villages near rivers or along the coast for planting and fishing. These villages sometimes needed to be protected with fences, depending on their friends and enemies among other tribes or Europeans. Abenaki villages were smaller than Iroquois villages, usually having about 100 people.

Most Abenaki built dome-shaped homes covered with bark, called wigwams. Some preferred oval-shaped longhouses. In winter, the Abenaki lived in smaller groups further inland. Their winter homes were bark-covered wigwams shaped like the teepees of the Great Plains Indians. For warmth, they lined the inside of their wigwams with bear and deer skins.

The Abenaki keep their traditions alive in many ways. For example, the Sokoki's government rules include a chief and a council of elders. They also list many traditions they follow, such as different dances and their meanings. During some dances, photography is not allowed to show respect for their culture. For others, people are asked to stand to show respect.

What are Abenaki hair and marriage traditions?

Traditionally, Abenaki men wore their hair long and loose. When a man found a girlfriend, he would tie his hair. When he got married, he would tie his hair with a piece of leather and shave all but the ponytail.

A modern spiritual version involves a man with a girlfriend tying and braiding his hair. When he marries, he keeps all his hair in a braid, shaving only the sides and back of his head. This hairstyle shows that an Abenaki man is engaged or married. Like in Christian weddings, couples can choose to exchange and bless wedding rings. These rings are a visible sign of their unity.

How did Abenaki society work?

The Abenaki were a farming society that also hunted and gathered food. Generally, the men hunted. The women took care of the fields and grew crops. In their fields, they planted crops in groups called "sisters." The three sisters—corn, beans, and squash—were grown together. The corn stalk supported the beans, and the squash covered the ground, which helped reduce weeds.

Children born to a married couple belonged to the mother's clan. The mother's oldest brother was an important guide, especially for boys. The biological father had a smaller role in raising the children.

Group decisions were made by reaching an agreement among everyone. Each family, band, or tribe would choose a spokesperson. Each smaller group would send its decision to a neutral person. If there was a disagreement, the neutral person would ask the groups to discuss it again. The goal was for everyone to fully understand the issue. If there wasn't full understanding, the discussion would pause until everyone understood.

When tribal members discuss issues, they think about the Three Truths:

- Peace: Is peace kept?

- Righteousness: Is it fair and moral?

- Power: Does it keep the group strong and whole?

These truths guide all group discussions. The goal is to reach a common agreement. If there is no agreement for a change, they decide to keep things as they are.

Why is storytelling important to the Abenaki?

Storytelling is a very important part of Abenaki culture. It is used not only for fun but also for teaching. The Abenaki believe stories have a life of their own and know how they are used. Stories were used to teach children how to behave. Children were not to be treated badly. So, instead of punishing a child, they would be told a story.

One story is about Azban the Raccoon. This is a story about a proud raccoon who challenges a waterfall to a shouting contest. When the waterfall doesn't respond, Azban dives into the waterfall to try to outshout it. Because of his pride, he is swept away. This story would be used to show a child the dangers of being too proud.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Abenaki para niños

In Spanish: Abenaki para niños