Maliseet facts for kids

| Person | Wəlastəkwew |

|---|---|

| People | Wəlastəkwewiyik |

| Language | Wəlastəkwey |

| Country | Wəlastəkok |

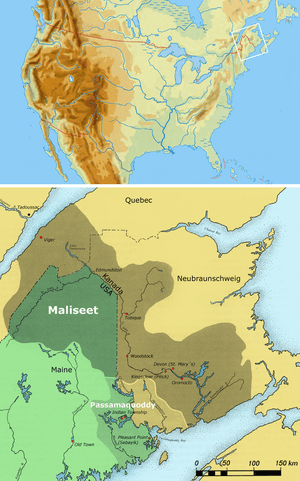

The Wəlastəkwewiyik, also known as the Maliseet (pronounced MAL-uh-seet), are an Algonquian-speaking First Nation. They are part of the Wabanaki Confederacy. These Indigenous people traditionally lived in the Wolastoq (Saint John River) valley and its smaller rivers. Their traditional lands stretch across parts of New Brunswick and Quebec in Canada, and parts of Maine in the United States.

The Houlton Band of Maliseet Indians lives along the Meduxnekeag River in Maine. Since 1776, they have been the first foreign treaty allies of the United States. They are a recognized tribe of Maliseet people. Today, some Maliseet people have also moved to other parts of the world. The Maliseet traditionally lived in a large homeland of forests, rivers, and coastal areas. This area was about 20 million acres, 200 miles wide, and 600 miles long, covering the Saint John River watershed.

Contents

Name of the People

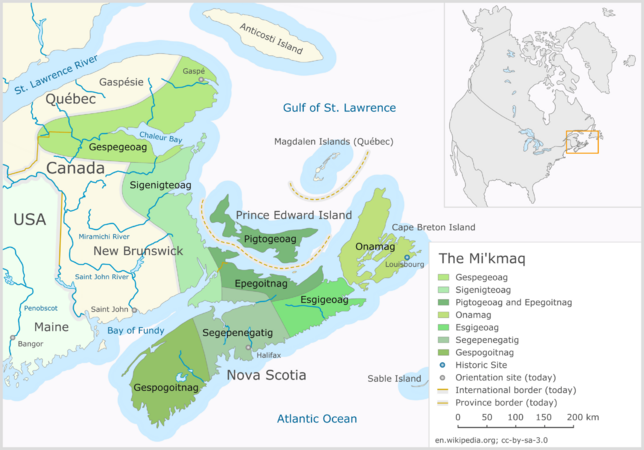

The people call themselves Wəlastəkwewiyik. In their language, Wəlastəkw means "bright river" or "shining river." So, Wəlastəkwewiyik simply means "People of the Bright River." The Maliseet (Malecite) have always been connected to the Saint John River. Their territory still reaches as far as the Saint Lawrence River. Their lands are next to the Miꞌkmaq people to the east, the Penobscot to the west, and the Passamaquoddy to the south. These groups also speak similar Algonquian languages.

The word Malesse'jik comes from the Miꞌkmaq language. It is thought to mean "He speaks slowly" or "He speaks differently." The Mi'kmaq used this word to describe the Maliseet language compared to their own. The exact meaning of the word today is not known. However, it is often wrongly translated as "he speaks badly, lazy, or broken." This term was used by the Mi'kmaq when they talked to early Europeans. The Europeans met the Mi'kmaq first. They then changed Malesse'jik to Malécite in French. Later, English colonists changed it again to Maliseet. The Europeans did not realize this was not the people's true name.

Around 1758, the names "Marichites" in French and "Maricheets" in English became more common.

Maliseet Communities Today

Here are some of the Maliseet communities:

- Maine, United States

- Houlton Band of Maliseet Indians (Metaksonekiyak Wolastoqewiyik)

- New Brunswick, Canada

- Kingsclear First Nation (Pilick Wəlastəkwewiyik)

- Madawaska Maliseet First Nation (Matowesekok Wəlastəkwewiyik)

- Oromocto First Nation (Welamoktuk)

- St. Mary's First Nation (Sitansisk Wolastoqiyik)

- Tobique First Nation (Wolastoqiyik Neqotkuk)

- Woodstock First Nation (Wetstak)

- Quebec, Canada

- Wolastoqiyik Wahsipekuk (Viger) First Nation (Wahsipekuk)

History of the Maliseet People

The 1600s

When Europeans first arrived, the Wəlastəkwewiyik lived in villages with protective walls. They grew crops like corn, beans, squash, and tobacco. Women also gathered and prepared fruits, berries, nuts, and other plants. Men hunted and fished, and women cooked the food. Early writings from the 1600s mention a large Malecite village at the mouth of the Saint John River. Later, their main village moved upriver to Meductic.

French explorers were the first to start trading furs with the Wəlastəkwewiyik. This trade became very important. The Wəlastəkwewiyik wanted some European goods because they were useful for their daily lives. French missionaries also set up churches, and some Wəlastəkwewiyik became Catholic. After many years of European settlement, many learned the French language. The French called them Malécite, using the Mi'kmaq name.

The Maliseet often met the Iroquois, who were powerful nations south of the Great Lakes, and the Innu to the north. Trading with European fishers and fur traders became a steady relationship for almost 100 years. Even though many Maliseet people got sick from European diseases, they kept their traditional hunting, fishing, and gathering spots along the coast and rivers. They lived along river valleys for trapping animals.

Colonial Wars

As more French and English settlers came to North America, they fought over land and the fur trade. Wars in Europe also led to fighting in North America. The fur trade became difficult because of the fighting between the French and English. There was also more fighting along the lower Saint John River.

During this time, Malecite women took on more of the work to support their families. They started farming crops that had only been grown further south before. Men continued to hunt, but it was harder to find animals. The Maliseet became important allies for the French against the English. For a short time in the late 1600s and early 1700s, Malecite warriors were often involved in battles. They became almost like a military group.

The 1700s

As the fighting slowly stopped in the early 1700s, and with fewer beavers for fur, the fur trade declined. It became hard for the Maliseet to go back to their old ways of life. European settlers started taking over their land, which made it difficult for the Maliseet to continue their seasonal farming along the river. Rich Europeans also discovered the area for hunting and fishing. They took all the good farmland along the Saint John River, which had belonged to the Maliseet. This forced many Indigenous people off more than a million acres of their best land.

The 1800s

The Maliseet continued some traditional crafts into the 1800s. They were especially good at building wigwams and birchbark canoes. Over the past two centuries, they had started using European metal tools, containers, guns, and different foods and clothes. When they made things from wood, bark, or baskets, or when they guided, trapped, and hunted, the Maliseet called it "Indian work."

Europeans started growing potatoes in Maine and New Brunswick. This created a new need for Maliseet baskets and containers. Other Maliseet people worked in pulp mills, construction, nursing, teaching, and business. Because many Maliseet people were struggling with hunger and moving around, the government set up the first Indian reserves. These were at The Brothers, Oromocto, Fredericton, Kingsclear, Woodstock, Tobique, Madawaska, and Cacouna.

Silas Tertius Rand was a missionary who studied languages. He translated parts of the Bible into Maliseet. These were published in 1863 and the Gospel of John in 1870.

The 1900s

The Maliseet people in New Brunswick faced challenges like unemployment and poverty. These were common for Indigenous people across Canada. However, they developed good ways to make decisions and share resources. They supported community projects in business, scouting, and sports. Some Maliseet people went on to higher education and became successful in different jobs. Individuals and families became important in fighting for Indigenous and women's rights. Others worked in Indigenous organizations, government, and community development. In 1996, there were 4659 registered Maliseet people.

Culture

The customs and language of the Maliseet are very similar to those of their neighbors, the Passamaquoddy (Peskotomuhkati). They are also close to the Algonquian-speaking Miꞌkmaq and Penobscot peoples.

The Wəlastəkwewiyik were different from the Miꞌkmaq because they did some farming. They also shared land with neighboring groups. The Wəlastəkwewiyik and Passamaquoddy languages are so similar that experts consider them slightly different ways of speaking the same language. They are usually studied together.

Two traditional Maliseet songs, a dance song and a love song, were written down by Natalie Curtis and published in 1907. The love song, as written by Curtis, has a unique rhythm and changes between happy and sad sounds.

Many other songs were recorded by an anthropologist named William H. Mechling. His old recordings of Maliseet songs are kept at the Canadian Museum of History. Many of these songs were forgotten by the community. This happened because of pressure to fit into Canadian culture, which led the Maliseet people to stop teaching their songs to young people. However, in the 2010s, Maliseet musician Jeremy Dutcher started a project. He listened to the old recordings and brought the songs back to life. His album Wolastoqiyik Lintuwakonawa came out in 2018. It won the 2018 Polaris Music Prize.

Traditional Plant Uses

The Maliseet people use the Abies balsamea (balsam fir tree) in many ways. They use the tree's sap to help with digestion. They also use the sticky resin, a tea made from the bark, and a mix of spruce and tamarack in their medicines.

They use the needles and branches for pillows and bedding. The roots are used as thread. The sticky resin is used to make canoe seams waterproof.

Current Situation

Today, in New Brunswick, there are about 7,700 Maliseet people with official status. They live in the Madawaska, Tobique, Woodstock, Kingsclear, Saint Mary's, and Oromocto First Nations. There are also 1,700 people in the Houlton Band in Maine. Another 1,200 are in the Viger First Nation in Quebec. The Brothers is a reserve made up of two islands in the Kennebecasis River. No one lives there, but it is used for hunting and fishing.

About 650 people still speak Maliseet, and about 500 speak Passamaquoddy. These speakers live on both sides of the border between New Brunswick and Maine. Most of them are older people. However, some young people have started learning and working to keep the language alive. There is an active program at the Mi'kmaq - Maliseet Institute at the University of New Brunswick. They work with native speakers to study the Maliseet-Passamaquoddy language. David Francis Sr., an elder from the Passamaquoddy living in Sipayik, Maine, has been a very important helper for this program. The Institute's goal is to help Native American students learn their native languages. The language expert Philip LeSourd has done a lot of research on the language.

The Houlton Band of Maliseet was invited to have a non-voting seat in the Maine Legislature. This started with the 126th Legislature in 2013. Henry John Bear, who teaches about treaty rights and is a tribal lawyer, fisherman, and forester, was chosen by his people for this seat.

Over hundreds of years, there has been a lot of marriage between Maliseet people and European settlers. Surnames linked to Maliseet family history include: Denis, Sabattis, Gabriel, Saulis, Atwin, Launière, Athanase, Nicholas, Brière, Bear, Ginnish, Solis, Vaillancourt, Wallace, Paul, Polchies, Tomah, Sappier, Perley, Aubin, Francis, Sacobie, Nash, Meuse. Also included are DeVoe, DesVaux, DeVou, DeVost, DeVot, DeVeau.

Notable Maliseet People

- Gabriel Acquin founded the Reserve created in 1867. This area is now part of St. Mary's First Nation.

- Sarah Anala is a social worker. She received the Order of Canada and the Queen Elizabeth II Diamond Jubilee Medal.

- Noel Bear was active during the “Aroostook War” (1838–39).

- Noël Bernard was a Malecite leader from 1781 to 1801.

- Jeremy Dutcher is a musician. He won the 2018 Polaris Music Prize for his album Wolastoqiyik Lintuwakonawa.

- Shayne Michael is a poet.

- Graydon Nicholas was the Lieutenant Governor of New Brunswick, Canada, from 2009 to 2014. In this role, he represented the Queen in the province.

- Sandra Lovelace Nicholas is a Maliseet activist. She is known for challenging unfair rules in the Indian Act in Canada. These rules took away the status of Aboriginal women if they married non-Aboriginal men. This law forced a male-focused idea of family on people who traditionally traced their family through the mother's side. In these cultures, children belonged to the mother's people and got their social standing from her family. Nicholas helped bring this issue to the United Nations Commission on Human Rights. She also worked hard for the 1985 law (Bill C31) that gave some rights back to First Nation women and their children in Canada. Keeping Aboriginal status for future generations is still an important issue for Maliseet and all Aboriginal groups. Nicholas was appointed to the Senate of Canada on September 21, 2005.

- Peter Lewis Paul was a Maliseet oral historian (1902-1989). He lived on the Woodstock Reserve (New Brunswick) on the Saint John River. He shared information with many university experts who studied languages, history, and cultures. He received many honors, including a Centennial Medal in 1969, an honorary Doctor of Law degree from the University of New Brunswick, and the Order of Canada in 1987.

- David Slagger represented the Maliseet people in the Maine House of Representatives.

Maps

These maps show where the Wabanaki Confederacy members lived (from north to south):

-

Maliseet, Passamaquoddy

-

Eastern Abenaki (Penobscot, Kennebec, Arosaguntacook, Pigwacket/Pequawket)

-

Western Abenaki (Arsigantegok, Missisquoi, Cowasuck, Sokoki, Pennacook)

See also

In Spanish: Maliseet para niños

In Spanish: Maliseet para niños

| Percy Lavon Julian |

| Katherine Johnson |

| George Washington Carver |

| Annie Easley |