Maliseet-Passamaquoddy language facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Maliseet-Passamaquoddy |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| skicinuwatu | ||||

| Native to | Canada; United States | |||

| Region | New Brunswick; Maine | |||

| Ethnicity | 5,500 Maliseet and Passamaquoddy (2010) | |||

| Native speakers | 355 in Canada (2016 census)e19 100 in the United States (2007) |

|||

| Language family |

Algic

|

|||

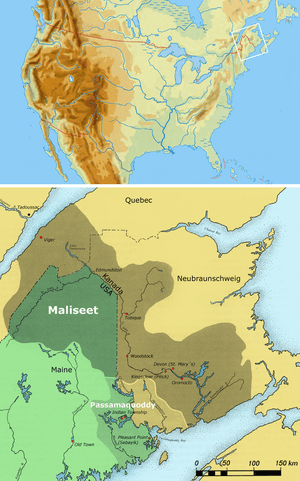

Distribution of Maliseet and Passamaquoddy peoples.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Maliseet-Passamaquoddy (skicinuwatu) is an endangered Algonquian language. It is spoken by the Maliseet and Passamaquoddy peoples. These groups live along the border between Maine in the United States and New Brunswick, Canada.

The language has two main ways of speaking, called dialects. The Maliseet dialect is mostly heard in the Saint John River Valley in New Brunswick. The Passamaquoddy dialect is spoken more in the St. Croix River Valley of eastern Maine. These two dialects are very similar, mostly differing in how words are pronounced.

Maliseet-Passamaquoddy was widely spoken in these areas until after World War II. Changes in schools and more people marrying outside their language group caused fewer children to learn or use the language. Today, only about 600 people speak both dialects in Canada and the U.S. Most of these speakers are older adults. Even though many young people do not speak the language, especially the Passamaquoddy dialect, there is a growing interest in teaching it. Community classes and some schools are now helping to bring the language back.

Contents

How the Language Sounds and is Written

The Maliseet-Passamaquoddy language has a special way of writing its sounds, called an orthography. This system uses 17 letters and an apostrophe.

Sounds and Spelling

The language has different sounds for consonants and vowels. Some consonants, like 'p' or 't', can sound a bit different depending on where they are in a word. For example, 'c' in peciye (he/she arrives) sounds like 'j' in "jump". But in pihce (far away), it sounds like 'ch' in "chair". This is a normal part of how the language works.

The language has six main vowel sounds. One of these is spelled with two letters, eh. There are also five diphthongs, which are sounds made by combining two vowel sounds. For example, aw sounds like "ow" in "cow".

Sometimes, a vowel sound might disappear from a word, especially if it is not emphasized. This is called syncope. For example, the word for "s/he is poor" might lose a vowel sound at the beginning. But if you say "I am poor," the vowel might stay because it is emphasized differently.

Also, some verbs change their vowel sounds depending on how they are used. For example, the verb stem for "smoke" (-wotom-) changes to wetomat when you say "when he/she smoked."

How Words are Built

In Maliseet-Passamaquoddy, words are built from smaller parts, like building blocks. This is called Morphology. It is a polysynthetic language, which means many small parts (called morphemes) are often combined into one long word. Each part usually has its own meaning.

Nouns and Their Classes

A key feature of Maliseet-Passamaquoddy is that all nouns (words for people, places, things) and pronouns (like "I," "you," "he") belong to a group called a noun class. Like other Algonquian languages, nouns are either animate (living) or inanimate (not living).

- Animate nouns include people, names, animals, and trees.

- Inanimate nouns include ideas like "prayer" or "happiness."

Sometimes, a word might seem like it should be one class but is actually the other. For example, "fingernail" is animate, but "heart" is inanimate. The easiest way to tell if a noun is animate or inanimate is by its plural form. Animate nouns end in -k when plural, and inanimate nouns end in -l.

Nouns can also show if they are the main focus of a sentence (proximate) or less important (obviative). For example, if you have two animate nouns in a sentence, one will be the main focus, and the other will be obviative.

Nouns can also have special endings to show things like:

- Absentative: Someone or something that is not there.

- Locative: Where something is (like "at the house").

- Vocative: When you are calling out to someone (like "Hey, John!").

Nouns can also have endings that mean "small" (diminutive) or "female" (feminine). These endings are added in a specific order.

Some nouns, like body parts or family words, must always have a "my" or "your" attached to them. For example, you can't just say "dog" in some cases; you have to say "my dog."

Pronouns: Who is Doing What?

There are different types of pronouns in Maliseet-Passamaquoddy:

- Personal pronouns: Like "I," "you," "he/she."

- Demonstrative pronouns: Like "this" or "that."

- Interrogative pronouns: Like "who?" or "what?"

- The word "other."

- A special filler pronoun: This is like saying "uh..." or "er..." in English. It changes its form to match the word you are about to say. For example, if you are about to say "table," the filler pronoun might be ihik. If you are about to say "Mary," it might be iyey.

Personal pronouns do not use plural endings like nouns. Instead, each form is unique. The language also has gender-neutral pronouns (meaning "he" or "she" is the same word). There are also different ways to say "we," depending on if "you" are included or not.

| Singular | Plural | |

|---|---|---|

| First person | nìl, nilá "I, me" | nilùn "we, us (not including you)" |

| kilùn "we, us (including you)" | ||

| Second person | kìl, kilá "you (one person)" | kiluwìw "you (many people)" |

| Third person | nékom "he/she, him/her" | nekomàw "they, them" |

Verbs: Actions and States

Verbs are words that show actions or states of being. They are built from "stems," which are like the core of the word. These stems can have different parts called "roots":

- Initial roots: Often describe qualities like color or how something is. For example, pus means "wet" in puskosone ("he/she has wet shoes").

- Medial roots: Can describe body parts, places, or shapes. For example, '-ptine- means "hand" or "arm" in tomiptinessu ("he/she breaks his/her own arm").

- Final roots: Show the main action or feeling. For example, '-hp(i)- means "eat" in nmemihp ("I have had enough to eat").

Verbs are also grouped by whether they are transitive (they need an object, like "kick the ball") or intransitive (they don't need an object, like "sleep"). Sometimes, an English sentence might use an object, but in Maliseet-Passamaquoddy, that object is built right into the verb. For example, "he/she makes baskets" is one word: posonut•ehk•e.

Verbs carry a lot of information in just one word. They can show:

- Gender: If the noun is animate or inanimate.

- Transitivity: If it needs an object or not.

- Person: Who is doing the action (I, you, he/she, they).

- Number: If it's one person or many.

- Hierarchy: Who is more important in the sentence (see below).

- Aspect: If the action is positive or negative.

- Mood: How the action is expressed (like a statement, a question, or a command).

- Tense: When the action happens (present, past).

There are different "modes" for verbs, which change how they are used in sentences:

- Independent indicative: For normal statements and yes/no questions.

- Changed conjunct: Often used in "when" or "why" questions.

- Unchanged conjunct: Used in "if" clauses.

- Subordinative: Used for actions that happen next or as a result. It can also be a polite command.

- Imperative: For direct commands.

- Conjunct imperative: For indirect commands (telling someone else to do something).

The language also has different "tenses" to show when something happened:

- Present: For actions happening now, or sometimes for past or future actions.

- Preterite: For actions that are already finished in the past.

- Dubitative preterite: For past actions that you are not sure about.

- Absentative: Refers to a noun that is not present.

How Sentences are Put Together

The way words are arranged in Maliseet-Passamaquoddy sentences is very flexible. This is because so much information is already packed into each word. Often, a single verb can be a complete sentence! For example, "I am eating" might be just one word.

Person Hierarchy: Who is More Important?

Maliseet-Passamaquoddy has a special system called a "direct-inverse" system. This means that when a verb has both a subject and an object, their endings change based on who is more important in the sentence. This is called the "person hierarchy."

Here's how the hierarchy works, from most important to least:

- 1st: You (singular or plural) and "we" (including you).

- 2nd: I and "we" (not including you).

- 3rd: He/she/they.

- 4th: Obviate forms (less important nouns).

- 5th: Inanimate nouns.

When the subject of a verb is higher on this list than the object, the verb uses a "direct" form. If the subject is lower than the object, the verb uses an "inverse" form. This system helps show who is doing what, even with flexible word order.

This hierarchy also affects how verbs show if an action is done to oneself (reflexive, like "I wash myself") or to each other (reciprocal, like "they help each other"). In these cases, the verb becomes intransitive, meaning it doesn't need a separate object.

Building Sentences

Because verbs carry so much meaning, sentences can be very short. There are not many strict rules about word order. One rule is that the word for "not" must come before the verb.

There is no word for "to be" (like "is" or "are") in Maliseet-Passamaquoddy. So, you can have sentences like "John tall" instead of "John is tall."

You can make longer, more complex sentences in several ways:

- Using words like "and" or "but" to connect ideas.

- Adding clauses that explain "when" or "why" something happened.

- Using commands, where the first verb is a direct command and the second verb explains what happens next.

Bringing the Language Back

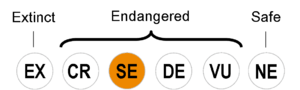

Today, Maliseet-Passamaquoddy is considered "Severely Endangered." This means that while adults might still use the language among themselves, it is not being passed down to children. However, there are many important efforts to bring the language back and teach it to both children and adults who did not learn it growing up.

Since 2006, a project called Language Keepers has been working with the Passamaquoddy and Maliseet communities. They record conversations of native speakers to document the language. They have filmed over 50 hours of natural conversations with 70 speakers. These recordings have been made into DVDs with English subtitles. This project has helped people who understand the language but can't speak it to start learning again. It has also helped find new leaders in the language community.

The Language Keepers project and other experts have also helped create the Passamaquoddy-Maliseet Dictionary. This dictionary was started in the 1970s and now has over 18,000 words. Many entries even have audio and video clips of native speakers saying the words.

Besides online resources, classes are being taught at the University of New Brunswick. These classes help different generations communicate and share knowledge and culture through the Maliseet-Passamaquoddy language.

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |