Indigenous peoples in Canada facts for kids

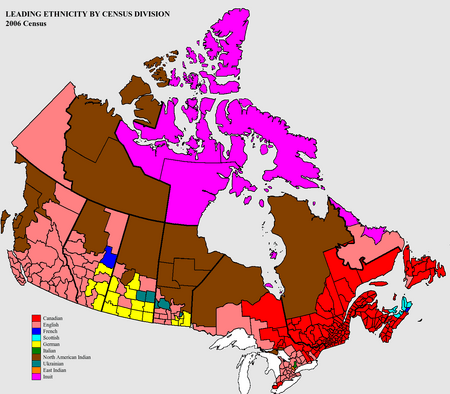

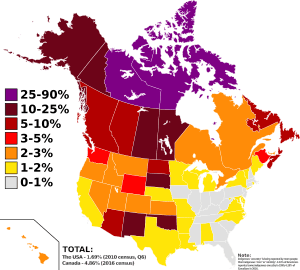

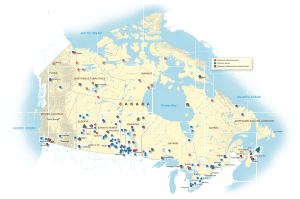

Indigenous peoples in Canada and the U.S., % of population by area

|

|

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 1,673,780 4.9% of the Canadian population (2016) |

|

| Languages | |

| Indigenous languages, Canadian English and Canadian French | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity (mainly Roman Catholicism and Anglican), Traditional Indigenous beliefs, Inuit religion, Mythologies of the indigenous peoples of the Americas | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Native Americans in the United States, Greenlandic Inuit, Indigenous peoples of the Americas |

Indigenous Peoples in Canada are the original inhabitants of the land now known as Canada. They are also called First Peoples. There are three main groups: the First Nations, the Inuit, and the Métis. While some old legal papers might use the word "Indian," and "Eskimo" was once used for Inuit, these terms are now often seen as disrespectful. The word "Aboriginal" is also used in some legal documents, but "Indigenous" is becoming more common and preferred.

People have lived in Canada for a very long time. Places like Old Crow Flats and Bluefish Caves show some of the earliest signs of human life here. Ancient cultures like the Clovis, Plano, and Pre-Dorset peoples lived here even before the current Indigenous groups. Archaeologists find tools like spear points, pottery, jewelry, and scrapers, which help them understand these old cultures.

Indigenous cultures in Canada often had lasting settlements, grew their own food, built special buildings, had organized societies, and traded with other groups. The Métis culture began in the mid-1600s when First Nations and Inuit people married Europeans, mostly the French. The Inuit had less contact with early European settlers. Over time, many treaties and laws were made between European newcomers and First Nations across Canada. Today, Indigenous peoples are working towards Self-Government, which means they want to manage their own history, culture, politics, healthcare, and money within their communities.

In 2016, about 1.67 million Indigenous people lived in Canada. This was about 4.9% of Canada's total population. This number included about 977,230 First Nations people, 587,545 Métis, and 65,025 Inuit. A large part of the population under 14 years old in Canada is of Indigenous background. There are over 600 recognized First Nations groups, each with its own unique culture, languages, art, and music. National Indigenous Peoples Day is celebrated to honor the cultures and contributions of Indigenous peoples to Canada's history. Many Indigenous people have become important leaders and role models, helping to shape Canada's culture.

Contents

Understanding the Words We Use

When we talk about Indigenous peoples in Canada, it's important to use the right words.

What Does the Law Say?

Section 35 of Canada's Constitution Act, 1982 says that "Aboriginal peoples of Canada" includes Indian, Inuit, and Métis peoples. "Aboriginal peoples" is a legal term that covers all Indigenous Canadian groups. However, many people now prefer the term "Indigenous peoples" because "Aboriginal" is starting to feel a bit old-fashioned.

The term "First Nations" became common in the 1970s, replacing "Indians" and "Indian Bands" in everyday talk. But on reserves, people often prefer to call themselves by their specific group, like "I am Haida" or "we are Kwantlens." "First Peoples" is another term that refers to all Indigenous groups: First Nations, Inuit, and Métis.

Why "Native" Isn't Always Best

Even though Canada is in North America, the term "Native American" is usually only used for Indigenous peoples in the United States. "Native Canadians" was sometimes used in Canada until the 1980s.

One problem with the word "native" is that it can mean just someone who was born in a certain place. For example, someone born in Calgary might say they are a "Calgary native." So, it doesn't always mean someone is Indigenous. Because of this, it's usually better to avoid using "native" when talking about Indigenous peoples.

The Term "Indian"

The Indian Act is a Canadian law that uses the term "Indian." This law says who is officially registered as an "Indian." This term is still used in legal documents like the Canadian Constitution. However, outside of these legal situations, using the word "Indian" can be seen as offensive. The Indian Act specifically does not include Inuit people.

The Term "Eskimo"

The word "Eskimo" is considered offensive in Canada and Greenland. Indigenous peoples in these areas prefer to be called Inuit. However, the Yupik people in Alaska and Siberia do not call themselves Inuit and prefer "Yupik" or "Eskimo." Their languages are different from Inuit languages. There isn't one single word that includes all Inuit and Yupik people across the Arctic.

Legal Groups of Indigenous Peoples

Besides their ethnic names, Indigenous peoples are also divided into legal groups based on their relationship with the Canadian government (called "the Crown"). Section 91(24) of the Constitution Act, 1867 gives the federal government the job of dealing with "Indians, and Lands reserved for the Indians." The government took over treaty agreements from the British and also signed new ones with First Nations in Western Canada. They also created the Indian Act in 1876 to manage their interactions with all First Nations.

First Nations people who are covered by the Indian Act are listed on the Indian Register and are called "Status Indians." Many First Nations people who don't have treaties, and all Inuit and Métis people, are not covered by the Indian Act. However, court cases have clarified that Inuit, Métis, and non-status First Nations people are all included under the term "Indians" in the Constitution Act, 1867.

History of Indigenous Peoples

Canada's history is deeply connected to its Indigenous peoples.

Ancient Times: Paleo-Indians

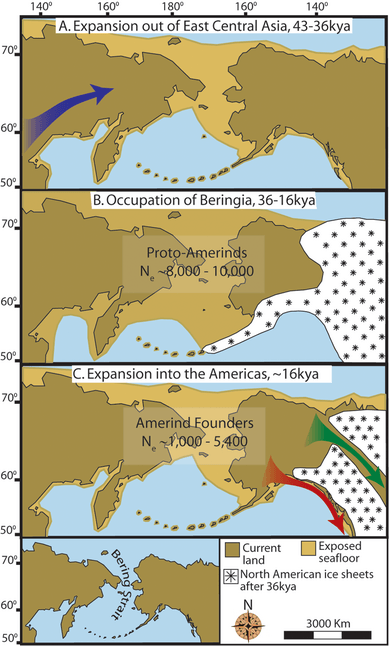

Scientists believe that North and South America were the last continents to be settled by humans. During the Ice Age, about 50,000 to 17,000 years ago, sea levels were lower. This allowed people to cross a land bridge called Beringia that connected Siberia to North America (Alaska). Most of Canada was covered in ice, so these early people stayed in Alaska for thousands of years.

Studies of Indigenous DNA suggest that the first people in the Americas came from one group that lived alone in Beringia for a very long time, possibly 10,000 to 20,000 years. Around 16,500 years ago, the ice started to melt, allowing people to move south and east into Canada and beyond.

The first people arrived in Canada at least 14,000 years ago. They likely followed large Ice Age animals like giant beavers, mammoths, and ancient caribou. One idea is that they walked through an ice-free path on the east side of the Rocky Mountains. Another idea is that they traveled along the Pacific Coast by foot or in simple boats. Evidence for this second route is now underwater because sea levels rose after the Ice Age.

The Old Crow Flats in Yukon was one of the few areas in Canada not covered by glaciers during the Ice Ages. It was a place where plants and animals could survive, and it shows signs of human life from about 12,000 years ago. Bluefish Caves in Yukon also has evidence of human activity from around the same time.

About 13,500 years ago, a culture called Clovis appeared in western North America. For a long time, people thought the Clovis people were the first widespread Indigenous group in the Americas. But in the last 30 years, new discoveries have shown other distinct cultures lived across the Americas at the same time.

After a cold period about 12,900 to 11,500 years ago, local cultures started to develop. The Folsom tradition, for example, used special spear tips called Folsom points to hunt bison.

The land bridge to Asia disappeared about 13,000 to 11,000 years ago. Along the coast of what is now British Columbia, there were large grasslands. Hunter-gatherers lived there from 13,000 to 9,000 years ago, leaving behind unique tools and animal bones. In 1992, X̱á:ytem in British Columbia became one of the first Indigenous spiritual sites in Canada to be officially recognized as a National Historic Site.

The Plano cultures were groups of hunter-gatherers who lived in the Great Plains of North America between 12,000 and 10,000 years ago. They used special spear points called Plano points to hunt bison, but also ate other animals like deer and raccoons. As the climate changed, they started to settle down more. Sites in Nova Scotia show that Plano-Indians had small hunting camps there around 11,000 to 10,000 years ago. They wore tailored clothes and lived in skin-covered tents to survive the cold.

Archaic Period: Settling Down and Growing

Around 10,000 years ago, Canada's climate became much like it is today. This led to more people moving around, growing plants, and a big increase in population across the Americas. Over thousands of years, Indigenous peoples in the Americas grew and developed many plant species that are now used as crops all over the world.

Canada's diverse climates and landscapes led to different Indigenous cultures and languages. Languages are very important to a people's identity, influencing their way of life and spiritual beliefs. Indigenous religions often focused on the idea that spirits live in nature and animals.

Archaeological finds from the Archaic period show that some people had higher status in their communities, based on what was buried with them. In British Columbia, the S'ólh Téméxw area has been continuously occupied by Indigenous people for 10,000 to 9,000 years. Early inhabitants were mobile hunter-gatherers, living in small family groups. The Na-Dene people lived in much of northwest and central North America starting around 8,000 BCE. They built large multi-family homes that they used seasonally for hunting, fishing, and gathering food for winter.

The Wendat peoples settled in Southern Ontario around 8,000 to 7,000 BCE, hunting caribou. Many First Nations cultures started relying on buffalo around 6,000 to 5,000 BCE. They would herd buffalo off cliffs to hunt them, like at Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump in Alberta, which was used for about 5,000 years.

On Canada's west coast, around 7,000 to 5,000 BCE, different cultures developed around salmon fishing. The Nuu-chah-nulth of Vancouver Island began whaling with long spears around this time. The Maritime Archaic people were sea-mammal hunters who lived along the Atlantic Coast of North America from about 7,000 BCE to 1,500 BCE. They built longhouses and traded over long distances. The "Red Paint People" of New England and Atlantic Canada, who lived from 3,000 BCE to 1,000 BCE, were known for using red ochre in their burial ceremonies.

The Arctic small tool tradition developed around 2,500 BCE. These people had special small tools, like tiny blades used on arrows or spears. These groups were ancestors of the Thule people, who were later replaced by the Inuit around 1000 CE.

Later Periods: Developing Cultures

The Old Copper Complex societies, from 3,000 BCE to 500 BCE, were part of the Woodland Culture. They used copper found in nature to make tools.

The Woodland cultural period lasted from about 2,000 BCE to 1,000 CE in Ontario, Quebec, and the Maritime regions. This period is known for the introduction of pottery. The Laurentian people of southern Ontario made the oldest pottery found in Canada. They also used tools like beaver tooth knives and chisels. People started living in one place more, growing crops like squash, corn, and beans.

The Hopewell tradition was an Indigenous culture that thrived along American rivers from 300 BCE to 500 CE. Their trade network reached the Canadian shores of Lake Ontario. Canadian groups like the Point Peninsula, Saugeen, and Laurel complexes were part of this network.

First Nations

By 500 BCE to 1,000 CE, First Nations peoples had settled and created trade routes across what is now Canada. Many different communities developed, each with its own culture and customs. For example, in the northwest were the Athapaskan, Slavey, Dogrib, Tutchone, and Tlingit peoples. Along the Pacific coast were the Tsimshian, Haida, Salish, Kwakiutl, Heiltsuk, Nuu-chah-nulth, Nisga'a, Senakw, and Gitxsan. On the plains were the Niisitapi (Blackfoot Confederacy), Káínawa, Tsuutʼina, and Piikáni. In the northern woodlands were the Nēhiyawak (Cree) and Chipewyan. Around the Great Lakes were the Anishinaabe, Algonquin, Haudenosaunee (Iroquois), and Wendat. Along the Atlantic coast were the Beothuk, Wəlastəkwewiyik (Maliseet), Innu, Abenaki, and Mi'kmaq.

Many First Nations groups had permanent settlements, practiced agriculture, built impressive structures, and had complex social systems. These cultures changed over time, and we learn about them through archaeological discoveries.

There are signs that Indigenous peoples had contact with people from other continents before Christopher Columbus arrived. First Nations people in Canada first met Europeans around 1000 CE, but regular contact began after Europeans started building permanent settlements in the 1600s and 1700s. Early European writings often described First Nations people as friendly, and they traded with Europeans. This trade often made stronger groups, like the Iroquois Confederation, even more powerful. In the 1500s, European fishing fleets visited Canada's eastern shores every year, and a fur trade also grew.

Important First Nations leaders include Joe Capilano, who met with King Edward VII to discuss land claims, and Ovide Mercredi, who was a leader during important talks about Canada's constitution and the Oka Crisis.

Inuit

The Inuit are descendants of the Thule culture, which started in western Alaska around 1,000 CE. They spread across the Arctic, taking the place of the Dorset culture. The Inuit called the Dorset people "giants" or "dwarfs." Researchers think the Dorset culture didn't have dogs or the same weapons as the Inuit. By 1300, the Inuit had settled in Greenland. The Inuit traded with more southern cultures, but arguments over land often led to fights.

Fighting was common among Inuit groups where there were enough people. For example, the Nunatamiut (Uummarmiut) who lived near the Mackenzie River delta often fought. But Inuit in the Central Arctic didn't have enough people for large-scale warfare. When the Thule culture arrived in Greenland in the 1200s, there were some Norse (Viking) settlements there. Norse items have been found at Inuit campsites, suggesting trade or raids. One Norse story talks about fighting "small people." By the 1300s, one of the Norse settlements was taken over by the Skræling (a Norse term for Indigenous people).

After the Norse colonies in Greenland disappeared, the Inuit had no contact with Europeans for about a century. By the mid-1500s, Basque fishers were working on the Labrador coast and had whaling stations. The Inuit didn't seem to bother their operations, but they did raid the stations in winter for tools, especially iron, which they used for their own needs.

Famous Inuit people include Abraham Ulrikab and his family, who were sadly put on display in a zoo in Germany, and Tanya Tagaq, a well-known traditional throat singer. Abe Okpik helped Inuit get surnames instead of disc numbers, and Kiviaq (David Ward) won the legal right to use his single Inuktituk name.

Métis

The Métis are people whose families came from marriages between Europeans (mostly French) and First Nations people like the Cree, Ojibway, Algonquin, Saulteaux, Mi'kmaq, and others. Their history goes back to the mid-1600s.

When Europeans first arrived in Canada, they relied on Indigenous peoples for their knowledge of fur trading and survival skills. To build strong friendships, European fur traders often married Indigenous women. The Métis homeland covers parts of British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, and the Northwest Territories.

Important Métis people include singer and actor Tom Jackson, Commissioner of the Northwest Territories Tony Whitford, and Louis Riel. Louis Riel led two resistance movements, the Red River Rebellion (1869–1870) and the North-West Rebellion (1885), fighting for Métis rights. He was later put on trial and executed.

The main languages of the Métis are Métis French or a mixed language called Michif. Michif is a blend of Cree and French. Today, most Métis speak English, with French as a strong second language, and many also speak various Indigenous languages. In the 1800s, a group of Métis called the Anglo-Métis or Countryborn were children of European (often Scottish or English) fur traders and Indigenous women. Their first languages were often Indigenous languages and English.

While Section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982 mentions the Métis, there has been a long discussion about how to legally define them. However, in 2003, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that Métis are a distinct people with important rights. Unlike First Nations people, there hasn't been a legal difference between "status" and "non-status" Métis.

Forced Assimilation: A Difficult Past

From the late 1700s, European Canadians and the Canadian government tried to make Indigenous cultures more like "Canadian culture." These efforts became very strong in the late 1800s and early 1900s, with plans to completely change Indigenous peoples and make them follow European ways. These policies, made possible by laws like the Gradual Civilization Act and the Indian Act, pushed for Christianity, settled living, farming, and European-style education.

Changing Beliefs

Christian missionaries had been working with Indigenous people since the 1600s. But making Indigenous people Christian became a government policy with the Indian Act in 1876. New rules meant that non-Christian Indigenous people couldn't speak in court, and traditional religious practices like the Potlatch were banned in 1884. Further changes in 1920 even stopped "status Indians" from wearing traditional clothing or doing traditional dances.

Settling Down and Reserves

The Canadian government also wanted Indigenous groups to stop moving around and settle in one place, believing this would make them easier to change. In the 1800s, they supported creating farming villages to encourage non-settled groups to farm. When these didn't work well, the government created Indian reserves with the Indian Act of 1876. These reserves came with many strict rules, like bans on alcohol, limits on voting in band elections, smaller hunting and fishing areas, and rules about visiting other reserves.

The Gradual Civilization Act in 1857 encouraged First Nations people to "enfranchise." This meant giving up their Indigenous rights and identity to become "more civilized" and like other Canadians. However, those who did often found they were still not fully accepted by Europeans.

Residential Schools

The most impactful government plan for assimilation was the Canadian residential school system. From 1847 until 1996, the Canadian government, working with Christian churches, ran 130 residential boarding schools. Indigenous children were taken from their homes and forced to attend these schools. While they offered some education, the schools were often underfunded, and children suffered from illness and abuse.

Because of these laws and policies that forced Indigenous peoples to adopt European ways, Canada broke international rules about human rights. The residential school system, which took Indigenous children from their families, has led many to believe that Canada could be accused of genocide. A legal case resulted in a large settlement in 2006, and in 2008, a Truth and Reconciliation Commission was set up. This commission confirmed the terrible harm these schools caused to children and the lasting problems between Indigenous Canadians and Canadian society.

In 2008, Prime Minister Stephen Harper officially apologized on behalf of the Canadian government for the residential school system.

Politics, Laws, and Agreements

Treaties: Promises Made

The Canadian government and Indigenous peoples started working together during the time of European colonization. This led to Numbered Treaties, the Halifax Treaties, the Indian Act, the Constitution Act of 1982, and court decisions. Indigenous peoples see these agreements as being between them and the Crown of Canada, not just the government of the day.

From 1871 to 1921, eleven treaties were signed between First Nations in Canada and the reigning Monarch. The Canadian government created the policies, sent out people to negotiate, and approved these agreements. These treaties are managed by Canadian Aboriginal law and overseen by the Minister of Crown–Indigenous Relations.

The Supreme Court of Canada has said that treaties "helped to bring together the existing rights of Indigenous peoples with the assumed rights of the Crown, and to define Indigenous rights." First Nations people believed that agreements like treaty 8 would last "as long as the sun shines, grass grows and rivers flow."

Indian Act: A Complex Law

The Indian Act is a federal law from 1876. It has been changed over 20 times, most recently in 1985 with Bill C-31. This Act explains how Reserves and Bands can operate and defines who is recognized as an "Indian."

In 1985, the Canadian Parliament passed Bill C-31, which made important changes to the Indian Act:

- It stopped unfair rules in the Indian Act, especially those that treated women differently.

- It changed what "status" means and allowed some Indigenous people who had lost their status or Band membership to get it back.

- It allowed Bands to create their own rules for who can be a member.

People who become Band members under these new rules might not be "Status Indians" under the federal law. Bill C-31 clarified which parts of the Indian Act would apply to Band members, especially concerning community life and land.

Royal Commission: Looking Back and Moving Forward

The Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples was a big study started by the Canadian government in 1991. Its goal was to look at issues facing Indigenous peoples in Canada. It examined past government policies, like residential schools, and suggested new ways for the government to work with Indigenous peoples. The Commission released its final report in 1996. This long report, with 4,000 pages, covered many topics and made 440 suggestions for big changes in how Indigenous and non-Indigenous people and governments interact in Canada. The report laid out a plan for change over 20 years.

Political Organizations: Working Together

Indigenous political groups in Canada have always varied in size, from small family groups to large confederacies like the Iroquois. Today, First Nations leaders from across Canada have formed the Assembly of First Nations. The Métis are represented by the Métis National Council, and the Inuit by Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami.

These modern political groups work with the Canadian government, especially with Crown–Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, on matters like land, rights, and agreements. Some First Nation groups choose to work independently and do not belong to these larger national organizations.

Culture: Rich Traditions and Modern Life

Many Indigenous words, inventions, and games are now part of everyday Canadian life. Think of the canoe, snowshoes, the toboggan, lacrosse, tug of war, maple syrup, and tobacco. Some words we use every day that come from Indigenous languages include "barbecue," "caribou," "chipmunk," "woodchuck," "hammock," "skunk," and "moose."

Many places in Canada, both natural spots and cities, have Indigenous names. The word "Canada" itself comes from a St. Lawrence Iroquoian word meaning 'village' or 'settlement'. The province of Saskatchewan gets its name from the Saskatchewan River, which in Cree means 'swift-flowing river'. Ottawa, Canada's capital city, comes from an Algonquin word meaning 'to trade'.

Modern youth groups like Scouts Canada and the Girl Guides of Canada include programs based on Indigenous stories, arts, crafts, and outdoor skills.

Indigenous cultural areas are often linked to how their ancestors lived, like hunting, fishing, or farming, and these areas often match Canada's different landscapes. For example, Indigenous peoples on the Pacific Northwest Coast focused on ocean and river fishing, especially salmon. On the plains, bison hunting was key. In the northern forests, moose were more important. Near the Great Lakes, people grew corn, beans, and squash. For the Inuit, hunting seals was their main way of getting food, along with caribou, fish, and other marine animals. The inukshuk, a rock sculpture made by stacking stones, is a famous symbol of Inuit culture and was the emblem of the Vancouver 2010 Winter Olympics.

Indian reserves are lands recognized by Canadian law for First Nations, often set aside by treaties. Some reserves are even inside cities. There are more reserves than there are First Nations, as some nations were given multiple reserves. Today, Indigenous people work in many different jobs and live in various places. Their traditional cultures still strongly influence their spirituality and political views. National Indigenous Peoples Day on June 21st celebrates the cultures and contributions of First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples in Canada.

Languages: A Rich Tapestry

Canada has 13 Indigenous language groups, with over 65 different dialects. Most are oral languages, but there are also two sign languages. Only Cree, Inuktitut, and Ojibwe have enough speakers to likely survive long-term. Two of Canada's territories have official status for Indigenous languages. In Nunavut, Inuktitut and Inuinnaqtun are official languages alongside English and French. Inuktitut is often used in the territorial government.

In the Northwest Territories, the Official Languages Act lists 11 different official languages: Chipewyan, Cree, English, French, Gwichʼin, Inuinnaqtun, Inuktitut, Inuvialuktun, North Slavey, South Slavey, and Tłįchǫ. While English and French are used most in government, citizens can ask for services in these other languages.

| Indigenous language | Number of speakers | Mother tongue | Home language |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cree | 99,950 | 78,855 | 47,190 |

| Inuktitut | 35,690 | 32,010 | 25,290 |

| Ojibway | 32,460 | 11,115 | 11,115 |

| Montagnais-Naskapi (Innu) | 11,815 | 10,970 | 9,720 |

| Dene | 11,130 | 9,750 | 7,490 |

| Oji-Cree (Anihshininiimowin) | 12,605 | 8,480 | 8,480 |

| Mi'kmaq | 8,750 | 7,365 | 3,985 |

| Siouan languages (Dakota/Sioux) | 6,495 | 5,585 | 3,780 |

| Atikamekw | 5,645 | 5,245 | 4,745 |

| Blackfoot | 4,915 | 3,085 | 3,085 |

| For a complete list see: Spoken languages of Canada | |||

Visual Art: Stories in Form

Indigenous peoples have been creating art for thousands of years, long before Canada became a country. Their art traditions spread across North America and are often grouped by cultural or language areas: Northwest Coast, Plateau, Plains, Eastern Woodlands, Subarctic, and Arctic.

Art styles are very different among these groups. Indigenous visual art often focuses on things that can be carried or worn, unlike European art which often focused on buildings. Indigenous art can also be used with other arts. For example, Shaman masks and rattles are used in dances, storytelling, and music. Artworks in museums show how Indigenous artists used new European trade goods like metal and glass beads in their creations. The unique Métis cultures have also created art forms that blend European and Indigenous styles. For many years, the Canadian government tried to force Indigenous peoples to change their culture. The Indian Act even banned traditional ceremonies like the Sun Dance and the Potlatch, and artworks showing them.

It wasn't until the 1950s and 1960s that Indigenous artists like Mungo Martin, Bill Reid, and Norval Morrisseau began to publicly bring back and create new Indigenous art traditions. Today, Indigenous artists work in all kinds of art forms in Canada. Two Indigenous artists, Edward Poitras and Rebecca Belmore, have even represented Canada at the Venice Biennale, a famous international art show.

Music: Rhythms and Songs

The Indigenous peoples of Canada have many different musical traditions. Music is usually for social gatherings (public) or ceremonies (private). Public music often involves dancing with rattles and drums. Private, ceremonial music includes songs with percussion, used for special events like Midewivin ceremonies and Sun Dances.

Traditionally, Indigenous peoples made their instruments from materials found in nature. First Nations people made rattles from gourds and animal horns, often decorating them beautifully. In forest areas, they made horns from birch bark and drumsticks from carved antlers and wood. Drums were usually made from carved wood and animal hides. These instruments provide the rhythm for songs, and songs provide the background for dances. Traditional First Nations people see song and dance as sacred. For many years after Europeans arrived, First Nations people were not allowed to practice their ceremonies.

Who Are Indigenous Peoples in Canada?

Canada's Constitution Act, 1982 recognizes three distinct groups of Indigenous peoples: First Nations, Inuit, and Métis. Under the Employment Equity Act, Indigenous people are a special group, along with women, visible minorities, and people with disabilities. This means they are not considered a "visible minority" by Statistics Canada.

In the 2016 Canadian Census, 1,673,780 Indigenous people were counted in Canada, making up 4.9% of the total population. This included 977,230 First Nations people, 587,545 Métis, and 65,025 Inuit. National groups that represent Indigenous peoples in Canada include the Assembly of First Nations, the Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, the Métis National Council, and others.

In 2016, Indigenous children aged zero to four made up 7.7% of all children in that age group in Canada. Sadly, they made up 51.2% of children in foster care in that age group.

In the 1900s, the Indigenous population in Canada grew ten times larger. After the 1960s, the number of babies dying on reserves dropped a lot, and the population grew quickly. Since the 1980s, the number of First Nations babies has more than doubled, and almost half of the First Nations population is under 25 years old.

Indigenous peoples believe their sovereign rights (their right to govern themselves) are still valid. They point to the Royal Proclamation of 1763, which is mentioned in the Canadian Constitution Act, 1982, and other international agreements that Canada has signed.

| Province / Territory | Number | % | First Nations (Indian) |

Métis | Inuit | Multiple | Other | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| British Columbia | 270,585 | 5.9% | 172,520 | 89,405 | 1,615 | 4,350 | 2,695 | |

| Alberta | 258,640 | 6.5% | 136,590 | 114,370 | 2,500 | 2,905 | 2,280 | |

| Saskatchewan | 175,020 | 16.3% | 114,565 | 57,875 | 360 | 1,305 | 905 | |

| Manitoba | 223,310 | 18.0% | 130,505 | 89,360 | 605 | 2,020 | 820 | |

| Ontario | 374,395 | 2.8% | 236,685 | 120,585 | 3,860 | 5,725 | 7,540 | |

| Quebec | 182,890 | 2.3% | 92,650 | 69,360 | 13,940 | 2,760 | 4,170 | |

| New Brunswick | 29,385 | 4.0% | 17,570 | 10,205 | 385 | 470 | 750 | |

| Nova Scotia | 51,490 | 5.7% | 25,830 | 23,315 | 795 | 835 | 720 | |

| Prince Edward Island | 2,740 | 2.0% | 1,870 | 710 | 75 | 20 | 65 | |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 45,725 | 8.9% | 28,370 | 7,790 | 6,450 | 560 | 2,560 | |

| Yukon | 8,195 | 23.3% | 6,690 | 1,015 | 225 | 160 | 105 | |

| Northwest Territories | 20,860 | 50.7% | 13,180 | 3,390 | 4,080 | 155 | 55 | |

| Nunavut | 30,550 | 85.9% | 190 | 165 | 30,140 | 55 | 10 | |

| Canada | 1,673,780 | 4.9% | 977,230 | 587,545 | 65,025 | 21,310 | 22,670 | |

| Source: 2016 Census | ||||||||

- A.% of the provincial or territorial population that is Aboriginal

- B.According to Statistics Canada, this figure "Includes those who identified themselves as Registered Indians and/or band members without identifying themselves as North American Indian, Métis or Inuit in the Aboriginal identity question."

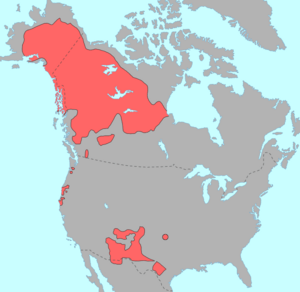

Experts often divide Indigenous peoples in the Americas into ten cultural areas, based on shared traditions. The Canadian regions are:

- Arctic cultural area

- Subarctic culture area

- Eastern Woodlands (Northeast) cultural area

- Plains cultural area

- Northwest Plateau cultural area

- Northwest Coast cultural area

Urban Indigenous Population

Across Canada, more than half (56%) of Indigenous peoples live in cities. The urban Indigenous population is the fastest-growing group in Canada.

| City | Urban Indigenous population | Percent of population |

|---|---|---|

| Winnipeg | 92,810 | 12.2% |

| Edmonton | 76,205 | 5.9% |

| Vancouver | 61,455 | 2.5% |

| Toronto | 46,315 | 0.8% |

| Calgary | 41,645 | 3.0% |

| Ottawa-Gatineau | 38,115 | 2.9% |

| Montreal | 34,745 | 0.9% |

| Saskatoon | 31,350 | 10.9% |

| Regina | 21,650 | 9.3% |

| Victoria | 17,245 | 4.8% |

| Prince Albert | 16,830 | 39.7% |

| Halifax | 15,815 | 4.0% |

| Sudbury | 15,695 | 9.7% |

| Thunder Bay | 15,075 | 12.7% |

See also

In Spanish: Amerindios de Canadá para niños

In Spanish: Amerindios de Canadá para niños

| Madam C. J. Walker |

| Janet Emerson Bashen |

| Annie Turnbo Malone |

| Maggie L. Walker |