Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast facts for kids

The Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast are made up of many different nations and tribes. Each group has its own unique culture and way of life. However, they also share some beliefs and traditions. For example, salmon is very important to them, both as food and as a spiritual symbol. They also share many ways of growing food and getting resources.

The term Northwest Coast is used by experts to describe the Indigenous groups living along the coast of what is now British Columbia, Washington State, parts of Alaska, Oregon, and Northern California. The term Pacific Northwest is mostly used in the United States.

This region once had the highest number of Indigenous people living in Canada.

Contents

- Nations of the Northwest Coast

- Eyak people

- Tlingit people

- Haida people

- Tsimshian people

- Gitxsan people

- Haisla people

- Heiltsuk people

- Nuxalk people

- Wuikinuxv people

- Kwakwakaʼwakw people

- Nuu-chah-nulth people

- Ditidaht people

- Makah people

- Coast Salish people

- Chimakum people

- Quileute people

- Willapa people

- Chinook people

- Tillamook people

- Daʼnaxdaʼxw Nation

- History of the Northwest Coast

- Material culture

- Society and culture

- Genetics

- See also

Nations of the Northwest Coast

The Pacific Northwest Coast once had the most people living in one area among Indigenous groups in Canada. The land and water provided rich natural resources like cedar trees and salmon. Because of these resources, complex cultures grew from these larger populations.

Many different nations developed in the Pacific Northwest. Each had its own history, culture, and society. Some cultures were very similar, sharing things like the importance of salmon. Others were quite different. Before Europeans arrived, and for a short time after, some groups would raid and attack each other. They sometimes took captives during these conflicts.

Eyak people

The Eyak people live in the Copper River Delta, north of the Alaska Panhandle. Most of them now live near the city of Cordova in Alaska.

Tlingit people

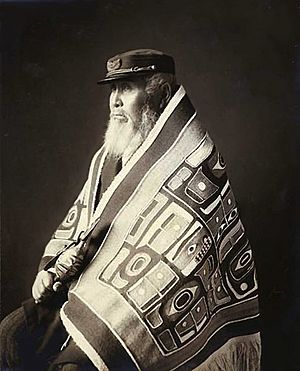

The Tlingit are one of the northernmost Indigenous nations on the Pacific Northwest Coast. Their own name for themselves is Lingít, which means "Human being."

The Tlingit society traces family lines through mothers. They developed a complex culture based on hunting and gathering in the temperate rainforest of the Alaska Panhandle and nearby inland areas of British Columbia.

Haida people

The Haida people are known as skilled artists who work with wood, metal, and design. They have also worked hard to protect their forests. The large forests of cedar and spruce where the Haida live are on land that is believed to be almost 14,000 years old.

Haida communities are found on Prince of Wales Island in Alaska and Haida Gwaii in British Columbia. They share borders with other Indigenous peoples like the Tlingit and Tsimshian. The Haida were also known for traveling long distances to trade and sometimes took captives.

Tsimshian people

The Tsimshian people, whose name means "People Inside the Skeena River," live around Terrace and Prince Rupert on the North Coast of British Columbia. Some also live in the southernmost part of Alaska on Annette Island. There are about 10,000 Tsimshian people, with about 1,300 living in Alaska.

In Tsimshian society, family lines are traced through mothers. A person's place in society was decided by their clan or family group. There are four main Tsimshian clans: Laxsgiik (Eagle Clan), Ganhada (Raven Clan), Gispwudwada (Killer Whale Clan), and Laxgibuu (Wolf Clan). Before Europeans arrived, people from the same half-group (like a Wolf and a Killer Whale) could not marry, even if they were not blood relatives. Marriages were only arranged between people from clans in different halves, for example, a Killer Whale and a Raven or Eagle.

Gitxsan people

The Gitxsan or Gitksan, meaning "people of the Skeena River," were once known with the Nisga'a as Interior Tsimshian. They speak a language closely related to Nisga'a, and both are related to Coast Tsimshian. Even though they live inland, their culture is part of the Northwest Coast culture area. They share many things, including a clan system, an advanced art style, and war canoes. They have a historical friendship with the nearby Wetʼsuwetʼen people. Together, they went to court against British Columbia in a case called Delgamuukw v British Columbia to protect their land rights.

Haisla people

The Haisla are an Indigenous nation living at Kitamaat in the North Coast region of British Columbia, Canada. The name Haisla comes from their word x̣àʼisla, meaning "(those) living at the rivermouth."

Heiltsuk people

The Heiltsuk are an Indigenous Nation from the Central Coast region of British Columbia, Canada. Their main communities are Bella Bella and Klemtu. The Heiltsuk are the descendants of several tribal groups who came together in Bella Bella in the 19th century. They prefer to call themselves Heiltsuk.

Nuxalk people

The Nuxalk people, also known as the Bella Coola, are an Indigenous people of the Central Coast. They are the northernmost of the Coast Salish cultures. Their Salishan language is unique and different from their coastal neighbors. They are believed to have been more connected to Interior Salish peoples before other groups moved south, separating the Nuxalk from their language relatives.

Wuikinuxv people

The Wuikinuxv, also known as the Owekeeno or Rivers Inlet people, speak a language related to Heiltsuk. Like other coastal peoples, they were master carvers and painters. They had a detailed system of rituals and clans. Their territory was centered around Owikeno Lake, a freshwater fjord at the head of Rivers Inlet.

Kwakwakaʼwakw people

The Kwakwakaʼwakw are an Indigenous people, numbering about 5,500, who live in British Columbia on northern Vancouver Island and the mainland. They prefer to call themselves Kwakwakaʼwakw. Their Indigenous language, Kwakʼwala, is part of the Wakashan languages family. The name Kwakwakaʼwakw means "speakers of Kwakʼwala." Today, less than 5% of the population speaks the language. Seventeen separate tribes make up the Kwakwakaʼwakw, who historically spoke Kwakʼwala.

Nuu-chah-nulth people

The Nuu-chah-nulth are an Indigenous people in Canada. Their traditional home is on the west coast of Vancouver Island. In earlier times, there were many more nations. However, diseases like smallpox caused some groups to disappear or join neighboring groups.

They were among the first Pacific peoples north of California to meet Europeans. A big disagreement between Spain and the United Kingdom over who controlled Nootka Sound happened around 1790. This dispute was settled when Spain agreed to give up its claim to the North Pacific coast. The Nuu-chah-nulth speak a Southern Wakashan language and are closely related to the Makah and Ditidaht.

Ditidaht people

The Ditidaht are a Southern Wakashan speaking people related to the Nuu-chah-nulth. Their territory is in the southern part of Vancouver Island.

Makah people

The Makah are a Southern Wakashan people and are closely related to the Nuu-chah-nulth. They are also known as whalers. Their territory is around the northwest tip of the Olympic Peninsula.

Coast Salish people

The Coast Salish are the largest of the southern groups. They are a loose collection of many tribes with different cultures and languages. Their territory stretches from the northern end of the Strait of Georgia, along the east side of Vancouver Island, covering most of southern Vancouver Island, and all of the Lower Mainland and Sunshine Coast. It also includes all of Puget Sound and the Olympic Peninsula. The Strait of Georgia and Puget Sound were officially named the Salish Sea in 2010.

Coast Salish cultures are quite different from their northern neighbors. As a whole, Coast Salish tribes generally trace family lines through both mothers and fathers. They are also one of the few peoples on the coast whose traditional lands are now major cities, like Victoria, Vancouver, and Seattle. Before Europeans arrived, the Coast Salish numbered in the tens of thousands, making them one of the most populated groups on the Northwest Coast.

Chimakum people

The Chimakum people spoke a Chimakuan language. Their traditional territory was in the area of Port Townsend. Because of conflicts with surrounding Salish peoples, their last major presence in the region ended in the mid-19th century. Some survivors joined neighboring Salish peoples, while others moved to join the Quileute.

Quileute people

The Quileute are a Chimakuan-speaking people. Their traditional territory is in the western Olympic Peninsula, around the Quillayute and Hoh Rivers.

Willapa people

The Willapa people traditionally spoke an Athabaskan language. They lived in southwestern Washington. Their territory was between Willapa Bay and the prairie lands around the Chehalis and Cowlitz Rivers. A related group, the Clatskanie, lived on the south side of the Columbia River in northwestern Oregon.

Chinook people

The Chinookan peoples were once one of the most powerful and numerous groups of tribes in the southern part of the Northwest Coast. Their lands were on both sides of the mouth of the Columbia River and stretched up the river. Their group of languages are known as Chinookan. This is different from the Chinook Jargon, which was a trading language partly based on it.

The Chinookan peoples were close friends with the Nuu-chah-nulth. They were also skilled canoe people. Before Europeans arrived, Chinook Jargon developed as a trading language, combining words from both Chinookan and Wakashan languages. The Chinookan peoples practiced taking captives, which they likely learned from the Nuu-chah-nulth. They also practiced cranial deformation, where infants' heads were gently shaped. Those without flattened heads were sometimes seen as lower in status.

One reason for the Chinookan peoples' importance was their location along the Columbia River. This river was a huge trade route. They were also near Celilo Falls, a fishing and trading hub used by many Indigenous peoples for 15,000 years.

Tillamook people

The Tillamook or Nehalem peoples spoke a Coast Salishan language. They lived roughly between Tillamook Head and Cape Meares on the northern Oregon Coast. The name 'Tillamook' comes from the neighboring Chinook-speaking Kathlamet people. Although their language was Coast Salish, it was somewhat different from their northern relatives. Their culture was also quite different, influenced by their southern neighbors. They relied less on salmon runs and more on fish trapping in estuaries, hunting, and gathering shellfish.

Daʼnaxdaʼxw Nation

The Daʼnaxdaʼxw Nation is a First Nations government in northern Vancouver Island in British Columbia, Canada. Their main community is Alert Bay. There are about 225 members of the Daʼnaxdaʼxw Nation. They are part of the Kwakiutl District Council.

History of the Northwest Coast

The Northwest Coast has a very long history of people living there. It is known for its many different languages, large populations, and rich cultural and ceremonial traditions. Experts are now finding that the economies of these people were more complex than once thought. Coast Salish peoples had smart ways of managing their land to keep ecosystems healthy. For example, they created "forest gardens" with plants like crabapple, hazelnut, and wild plum. Many groups have "First Generation Stories" that tell how their group, and often humans, came to be in specific places along the coast.

The mild climate and many natural resources on the Northwest Coast allowed a complex Indigenous culture to grow. People living in what is now British Columbia, Washington, and Oregon could get food and resources without too much effort. This gave them time and energy to create beautiful art and crafts, and to develop religious and social ceremonies.

European arrival

The Indigenous populations were greatly harmed by epidemics of infectious diseases, especially smallpox. These diseases were brought by European explorers and traders. Before Europeans settled, various reports from explorers described tribes in the area showing signs of smallpox. For example, a British ship captain named Nathaniel Portlock expected to see many people but found only a few, and the oldest man was "marked with the small-pox."

There are many ideas about how smallpox reached the Pacific Northwest. One idea is that an outbreak in central Mexico in 1779 spread north to the Shoshone in 1781. From there, it could have spread to the lower Columbia River and Strait of Georgia through trade between different tribes. Spanish trips to the Northwest Coast in the late 1700s are also thought to have spread smallpox. Another idea is that the outbreak started in Russia in 1769 and spread through Russian explorers to Alaska and down the Pacific Coast. There were also later smallpox epidemics, like the terrible 1862 Pacific Northwest smallpox epidemic.

Because the native population had never been exposed to these diseases before, many tribes may have lost as much as 90% of their people. This made it easier for European and American settlers to colonize the Pacific Northwest.

Today's times

Today, the lives of these Indigenous peoples vary, especially in their relationship with Canada and the United States. In Canada, Indigenous peoples are one of the fastest-growing groups, with a young and increasing population. However, important issues still exist due to colonial laws and the Canadian Indian residential school system. Many unfair parts of the Indian Act (a federal law for First Nations) were removed in 1951. First Nations people were given the right to vote in 1960. The 1951 change to the Indian Act also lifted the potlatch ban, which had made traditional culture go underground. Since 1951, ceremonial practices and the potlatch have widely returned along the coast.

One recent development is the return of ocean-going cedar canoes. This revival started in the late 1980s with early Haida and Heiltsuk canoes. It spread quickly after the Paddle to Seattle in 1989 and the 1993 'Qatuwas canoe festival. Many other journeys to different places along the coast have happened. These trips are now known as Tribal Canoe Journeys.

Material culture

Both the sea and the land provided important food and materials for Indigenous Peoples of the Northwest Coast. Many of these resources needed to be managed carefully to ensure they would always be available. Historians and experts have found evidence of farming and environment management strategies used by First Nations peoples for centuries. Practices like digging, tilling, pruning, controlled burning, fertilizing, and creating habitats helped Indigenous groups manage their environment. This encouraged more resources to grow for continued harvesting.

The Pacific salmon was especially important for food and culture in the Northwest. So much so that the Native Nations of the region call themselves the Salmon People. Salmon were caught with hooks, lines, or small nets. They were then pierced with cedar skewers and roasted or smoked over fires. Other ways of catching them included traps, baskets, spears, and lures. Tribes relied on dried or smoked salmon during the winter. So, the first fresh fish caught in the spring was celebrated with a big ceremony.

Hunting, both on land and sea, was also an important food source. At sea, this included hunting whales, sea lions, porpoises, seals, and sea otters. On land, they hunted deer, moose, and elk. The plentiful supply of these animals meant that the tribes became successful.

The most important plant in the diet of Northwest Native Americans was the bulb of the Camassia plant. Indigenous peoples actively managed and grew camassia by clearing land, tilling, weeding, and planting bulbs. Camas plots were harvested by individuals or family groups who were recognized as the caretakers of that plot.

Indigenous peoples of the Northwest Coast harvested root crops by digging and tilling. Using a digging stick made from hard wood, they would work the ground. This loosened the soil, making it easier to remove root crops whole and undamaged. It also allowed roots and bulbs to grow more freely and abundantly.

Native peoples of the Pacific Northwest also ate a variety of fruits and berries. A favorite food was the salmonberry Rubus spectabilis, named because it was traditionally eaten with salmon and salmon roe. Blackberries Rubus and evergreen huckleberries Vaccinium ovatum (eaten fresh or dried into cakes) were also popular. Red huckleberry Vaccinium parvifolium was eaten and used as fish bait because it looked like salmon eggs. The Oregon grape Mahonia nervosa was sometimes eaten, mixed with sweeter berries to make it less sour.

Society and culture

Potlatch ceremony

A potlatch is a very important event where people gather to celebrate something special. This could be raising a totem pole or choosing a new chief. These potlatches were often held in friendly competition, showing off a family's wealth within a tribe.

During a potlatch, the chief would give valuable gifts to visiting people. This showed his power and importance. By accepting these gifts, the visitors showed they approved of the chief. There were also big feasts and displays of wealth, like burning items or throwing things into the sea, just to show how rich the chief was. Groups of dancers performed elaborate dances and ceremonies. These dancers were part of special "dancing societies." Watching these performances was considered an honor. Potlatches were held for many reasons: to confirm a new chief, for coming-of-age ceremonies, tattooing or piercing ceremonies, joining a secret society, marriages, a chief's funeral, or celebrating a battle victory.

Music

Among the Indigenous people of the Pacific Northwest Coast, music has many different uses and expressions. While some groups have more cultural differences than others (like the Coast Salish and the northern nations), many similarities remain.

Some instruments used by Indigenous peoples were hand drums made of animal hides, plank drums, log drums, box drums, along with whistles, wood clappers, and rattles. Many instruments were used mostly in the potlatch, but also in other celebrations throughout the year.

Songs are used with dancing, but also for celebration, sometimes without dancing. Most singing is done by the community. There are some solo parts, often when a lead singer starts the first line of each round of a song. For some ceremonies, men and women would sing solo songs without any other person or drum.

Music in this area is usually slow and accompanied by a drum. Its main purpose is spiritual; music honors the Earth, Creator, Ancestors, and all parts of the supernatural world. Sacred songs are often not shared widely. Women and men, and families, own their own songs as property. These songs can be inherited, sold, or given as a gift to an important guest at a Feast. Professionals existed in some communities, but music is taught and then practiced. For some nations, people who made musical errors were shamed. Songs often use octave singing, but instead of going up and down the scale smoothly, they often jump notes. Vocal rhythmic patterns are often complex and go against the steady drum beats. The tribes would dance in groups in circles.

Art

Creating beautiful and useful objects was a way for all tribal communities to pass down stories, history, wisdom, and property from one generation to the next. Art connected Indigenous people to the land by showing their histories on totem poles and the Big (Plank) Houses of the Pacific Northwest coast. The symbols reminded them of their birthplaces, family lines, and nations.

Because of the many natural resources and the wealth of most Northwest tribes, people had plenty of free time to create art. Many artworks served practical purposes, like clothing, tools, weapons, transportation, cooking items, and shelter. But others were purely for beauty.

For the Pacific Northwest Coast peoples, spiritual beliefs, the supernatural, and the importance of the environment were central to daily life. So, it was common for their belongings to be decorated with symbols, crests, and totems. These represented important figures from both the seen and unseen worlds.

Often, different northern tribes would decorate their possessions with symbols that represented their tribe as a whole (like a clan). This often showed the difference between tribal groups. Such symbols could be compared to a coat of arms or a country's flag on a ship.

After Europeans arrived, Indigenous artifacts suddenly became very popular to collect for museums. Many tribal groups had their precious items taken by eager collectors.

In recent years, many Indigenous organizations have been asking for the return of some of their sacred items, like masks and regalia, which are important parts of their cultural heritage.

Genetics

Haplogroup Q1a3a is a Y chromosome haplogroup often found in Indigenous peoples of the Americas. The Q-M3 change appeared in the Q family tree about 10 to 15 thousand years ago, as people were migrating across the Americas. The Na-Dené, Inuit, and Indigenous Alaskan populations have different haplogroup Q (Y-DNA) changes compared to other Indigenous Americans. This suggests that the ancestors of people living in the northern parts of North America and Greenland came from later migrations.

Genetic studies of HLA genes link the Ainu people of Japan to some Indigenous peoples of the Americas, especially those on the Pacific Northwest Coast like the Tlingit. Scientists suggest that the main ancestors of the Ainu and some Native American groups can be traced back to ancient groups in Southern Siberia.

See also

| Lonnie Johnson |

| Granville Woods |

| Lewis Howard Latimer |

| James West |