Chinook Jargon facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Chinook Jargon |

|

|---|---|

| chinuk wawa, wawa, chinook lelang, lelang, chinook | |

| Native to | Canada, United States |

| Region | Pacific Northwest (Interior and Coast): Alaska, British Columbia, Washington State, Oregon, Idaho, Montana, Northern California |

| Native speakers | More than 640 (at least 3 native adult speakers alive in 2019 based on estimates from the Chinook Jargon Listserv archives) (2020)e21 |

| Language family | |

| Writing system | De facto Latin, historically Duployan; currently standardized IPA-based orthography |

| Official status | |

| Official language in | De facto in Pacific Northwest until about 1920 |

Chinook Jargon (also called Chinuk Wawa or Chinook Wawa) is a special language. It started as a pidgin language in the Pacific Northwest. A pidgin is a simplified language that helps people who speak different languages talk to each other.

This language became popular in the 1800s. It spread from the Columbia River area to places like Oregon, Washington, British Columbia, and parts of Alaska. It even reached Northern California, Idaho, and Montana. Sometimes, it changed into a creole language. A creole is a pidgin that becomes a main language for a group of people.

Chinook Jargon uses many words from the Chinook language. About 15% of its words come from French. It also borrowed words from English and other languages. The special writing system for Chinook Jargon is called Duployan shorthand. A French priest named Émile Duployé created it.

Many words from Chinook Jargon are still used today in the Western United States and British Columbia. People see it as an important part of the history of the Pacific Northwest. The language has its own simple grammar system, which makes it easy to learn.

Contents

What is Chinook Jargon Called?

Most books in English still use the name "Chinook Jargon." But some language experts prefer "Chinuk Wawa." They use the spelling 'Chinuk' instead of 'Chinook'. This is especially true for the form of the language used in Grand Ronde, Oregon.

People who spoke the language long ago didn't usually say "Chinook Wawa." They often called it "the Wawa" or "Lelang." "Lelang" comes from the French words for "the language" or "tongue." The word "Wawa" itself means speech or words. Even today, some people might say "have a wawa" to mean "have a talk."

The name for the Jargon changed depending on where it was spoken. For example, in the Fraser Canyon area of British Columbia, it was sometimes called skokum hiyu. In other places, people simply called it "the old trade language" or "the Hudson Bay language."

History of Chinook Jargon

How Chinook Jargon Started

Experts have debated whether Chinook Jargon started before or after Europeans arrived.

Some believe it began before Europeans came. They think it was a way for different Native American groups to communicate. This was important because the region had many different languages. Later, it added words from European languages like French and English.

Others think it started after European traders arrived. They suggest it began in Nootka Sound. This was a way for Russian and Spanish traders to talk with Native peoples. Then, it spread south because of trade.

A linguist named Barbara Harris thinks both ideas might be true. She believes the different ways the language started probably mixed together. By 1840, for some speakers, it had become a main language, not just a trade language.

How Chinook Jargon Was Used

In British Columbia, many people learned to read and write Chinook Jargon. They used a special newspaper called Kamloops Wawa. This newspaper was written using Duployan shorthand. Because of this, Chinook Jargon started to have its own stories and writings. These included parts of the Bible, classic stories, and local news.

In Oregon, Native Americans, fur trappers, traders, and pioneers used Chinook Jargon a lot. This was especially true from the 1830s to the 1870s. In Portland, people used it for trade between pioneers and Native Americans. After 1900, some pioneer families still spoke it to show they were early settlers.

Many Oregonians used Jargon in everyday talks. They used it to add humor or to show how much they knew about Oregon's history. While non-Native people stopped using it as much, some Native American groups in Oregon kept speaking it.

In Seattle, Chinook Jargon was used until around World War II. It was especially common among members of the Arctic Club. This made Seattle one of the last cities where the language was widely spoken.

One expert, Nard Jones, estimated that about 100,000 people spoke Chinook Jargon in the 1860s. It was used in newspapers, in schools to teach Native students, by shopkeepers, and in courts. Priests used it to teach religion, and children even used it when playing.

The language was most popular from about 1858 to 1900. Its use declined after the Spanish flu and World War I. By the 1940s, some people were still born speaking it. But by 1962, only about 100 speakers were left. However, in 2010, the US Census counted 640 native speakers.

How Chinook Jargon Changed

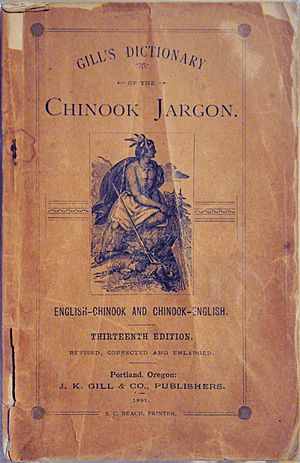

Chinook Jargon was most used in the 1800s. Many dictionaries were published then. These helped settlers talk with the First Nations people. Some people in Vancouver, British Columbia, even spoke Chinook Jargon as their first language. They used it at home instead of English.

The language was influenced by people's accents and words from their own languages. For example, when Kanakas (people from Hawaii) married into families, their version of the Jargon might have included Hawaiian words.

Chinook Jargon became the main language in homes with people from different backgrounds. It was also used in workplaces like canneries and logging camps. It stayed the language of these workplaces until the mid-1900s. During the Gold Rush, gold miners and engineers used it. Later, cannery workers, loggers, and ranchers used it. It's possible that at one point, more people in British Columbia spoke Chinook Jargon than any other language, even English.

Historian Jane Barman wrote that Chinook Jargon was important for everyday talks between Native people and Europeans. It had about 700 words from the Chinook and Nootka peoples, and from French and English. Leaders like James Douglas often spoke Chinook Jargon to Native people. Even in schools for Native children, Chinook Jargon was used for teaching.

A special form of Chinook Jargon, called Chinuk Wawa, is still spoken as a first language by some people in Oregon. This is similar to how the Métis people in Canada speak Michif. This Chinuk Wawa is a true creole language. It is different from the Chinook Jargon that spread widely.

There is evidence that in some places, like around Fort Vancouver, the Jargon became a creole language early on. This happened among the mixed French, Métis, and Hawaiian people there. At Grand Ronde, many different tribes were brought together. Chinuk Wawa became their common language, which led to it becoming a creole.

How Chinook Jargon is Written

There are a few main ways to spell Chinook Jargon words. But each writer often had their own slight differences.

- English, French, and German-Based Spelling: This way uses the original English or French spellings for words that came from those languages. Other words are spelled roughly how they sound, using English, French, or German rules. For example, "cloochman" for "woman" or "wife."

- Approximate Sound-Based Spelling: This way focuses on how the words actually sound. So, "cloochman" might be written as "tlotchmin."

- IPA-based spelling for computers: This was used in the 1990s when it was hard to type special symbols. It uses regular letters to represent sounds.

- IPA-based Grand Ronde Spelling: This is a specific spelling system used only by speakers of the Grand Ronde dialect in Oregon.

Chinook Jargon Today

Chinook Jargon is seen as a shared cultural heritage in the Pacific Northwest. Historians know about it, even if they can't speak it. Mentions of the language were common in historical writings before 1900.

Today, many people don't know about Chinook Jargon. But its memory probably won't disappear completely. Many words are still used in Oregon, Washington, British Columbia, the Yukon, and Alaska. Older people might still remember it. Even though speaking it was sometimes discouraged, it was a working language in many towns and workplaces. This was especially true in places with many different ethnic groups, like canneries.

Place names throughout the region have Jargon names. Words are also kept alive in industries like logging and fishing. Chinook Jargon was a language that helped many cultures connect. Because it hasn't completely died out, people are working to bring it back into everyday speech.

As of 2009, the Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde Community of Oregon are working to save Chinook Jargon. They have a preschool where children learn only in Chinuk Wawa. This helps children become fluent in the language. The Tribes also offer Chinuk Wawa lessons in Eugene and Portland. Lane Community College offers classes in Chinuk Wawa too.

In 2012, the tribe published a Chinuk Wawa dictionary. It helps people learn the language. In 2014, they even made an app for learning Chinuk Wawa.

In 2001, Iona Campagnolo, a Canadian politician, ended her speech in Chinook Jargon. She said, "konoway tillicums klatawa kunamokst klaska mamook okoke huloima chee illahie." This means "everyone was thrown together to make this strange new country [British Columbia]."

An art display in Vancouver, British Columbia, also features Chinook Jargon. It's called "Welcome to the Land of Light." A short film called Small Pleasures uses Chinook Jargon to show how people from different cultures talked in the 1890s.

Bringing Chinuk Wawa Back at Grand Ronde

In 1997, the Grand Ronde reservation in Oregon hired Tony Johnson. He is a Chinook linguist. His job was to lead their language program. They chose Chinuk Wawa because it was strongly connected to their Native identity. It was also the only Native language still spoken at Grand Ronde.

Before this, Eula Holmes taught formal Chinuk Wawa classes from 1978 to 1986. Her sister, Ila, also held informal classes. Henry Zenk joined the project in 1998. He had studied the language in the 1970s and 80s. They started community classes in 1998. The dictionary was released in 2012. This dictionary was made from the Chinuk Wawa spoken by Grand Ronde elders.

In 2001, the tribe started an immersion preschool. This means children learn only in Chinuk Wawa. In 2004, a kindergarten was started. It has grown to a half-day immersion program for students from kindergarten to fourth grade. These classes are at Willamina Elementary School.

Chinuk Wawa classes also started at Willamina High School in 2011. Students there can earn high school and college credit. Lane Community College also offers a two-year course in Chinuk Wawa.

In 2020, an online magazine called Kaltash Wawa was started. It uses British Columbia Chinuk Wawa and a special alphabet called Chinuk Pipa.

Chinook Jargon's Influence on English

Some words in English, especially in British Columbia and the Pacific Northwest, come from Chinook Jargon. This is because the Jargon was widely spoken until the mid-1900s. These words are also found in Oregon, Washington, Alaska, and parts of Idaho and Montana.

Here are some Chinook Jargon words still used in English:

- Cheechako — This means a newcomer. It comes from chee ("new") and chako ("come"). It was used for non-Native people.

- Chuck — Means water. So, saltchuck means "salt water." Names like Colchuck Peak come from this word.

- Cultus — Means bad, worthless, or useless. Cultus iktus means "worthless stuff."

- Hiyu — Less common now, but sometimes means a party or gathering. It comes from the Jargon word for "many" or "lots of." The HiYu Summer Festival in West Seattle is named after this.

- Iktus — Means "stuff."

- Klootchman or klootch — In Jargon, it means "a woman" or female. For example, klootchman kiuatan is a mare (female horse). It's still used in some areas to mean a First Nations woman.

- Masi — In northern British Columbia and the Yukon, this word means "thank you." It comes from the French word merci.

- Moolah — This slang term for money might come from the Jargon word moolah, meaning "mill." Lumber mills were a source of wealth.

- Mucky muck or muckamuck — In Jargon, this means "plenty of food." It came to mean someone who lives well, or an important person. High muckety muck means a very important person.

- Potlatch — A ceremony among some tribes with food and gift-giving. Today, it sometimes means a potluck dinner.

- Quiggly, quiggly hole — Refers to the remains of an old Native American pit-house. It comes from kickwillie, meaning "down" or "underneath."

- Siwash — This word means a First Nations man. It comes from the French word sauvage (savage). Its meaning can be seen as negative. However, when pronounced a certain way in Grand Ronde, it means a Native American.

- Skookum — A very useful word! It can mean "able," "strong," "big," "genuine," or "reliable." A skookum house is a jail. If something is "skookum," it means it's strong and reliable.

- Tenas — Means "small."

- Tillicum — Means "people," "person," or "family."

- Tolo — In Western Washington, this means a semi-formal dance where girls ask boys. It comes from the Jargon word for "to win."

- Tyee — Means leader, chief, or boss. A Big Tyee is an important person. In fishing, a very large chinook salmon is called a Tyee. The Hyas Klootchman Tyee was the historical term for Queen Victoria. The word tyee is still used in some places to mean "boss."

Famous People Who Spoke Chinook Jargon

Many non-Native people learned and spoke Chinook Jargon. Here are a few:

- Francis Jones Barnard

- Sir Matthew Baillie Begbie (a judge)

- Franz Boas (a famous anthropologist)

- Sir James Douglas (a governor)

- Joshua Green (a banker)

- Phoebe Goodell Judson (a pioneer)

- Father Jean-Marie-Raphaël Le Jeune (a priest)

- John McLoughlin (a fur trader)

- Robert William Service (a poet)

- Sam Sullivan (a politician)

| Chris Smalls |

| Fred Hampton |

| Ralph Abernathy |