Fort Vancouver facts for kids

Quick facts for kids |

|

|

Fort Vancouver National Historic Site

|

|

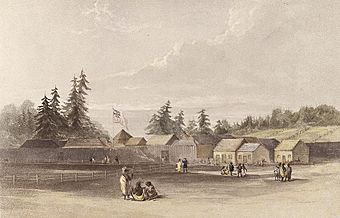

Fort Vancouver in 1845

|

|

| Lua error in Module:Location_map at line 420: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). | |

| Location | Vancouver, Washington, United States |

|---|---|

| Built | Winter 1824–1825 |

| NRHP reference No. | 66000370 |

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1966 |

Fort Vancouver was a very important place in the Pacific Northwest long ago. It was a British fur trading post built in the early 1800s. At that time, the land was called Oregon Country, and both Britain and the United States claimed it.

The Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) owned Fort Vancouver. It was their main base in a large area known as the Columbia District. The fort was built in the winter of 1824–1825. It was named after Captain George Vancouver, a British explorer who sailed along the Pacific Coast.

Fort Vancouver was located on the north bank of the Columbia River. It was the center of the fur trade for the entire region. Every year, ships brought goods and supplies from London across the Pacific Ocean. Other supplies came overland from Hudson Bay. Local Indigenous peoples would trade animal furs at the fort for these goods. The furs from Fort Vancouver were then sent all over the world. Some even went to China to be traded for Chinese products. At its busiest, Fort Vancouver managed 34 smaller outposts, 24 ports, six ships, and 600 workers.

In 1846, Great Britain and the United States signed the Oregon Treaty. This treaty gave the land around Fort Vancouver to the United States. Even though the treaty said the HBC could keep trading, it became too difficult. Fort Vancouver soon closed down.

Today, the fort is in Vancouver, Washington. It has been saved and is now the Fort Vancouver National Historic Site. You can visit a full-size copy of the old Hudson's Bay Company outpost there.

Contents

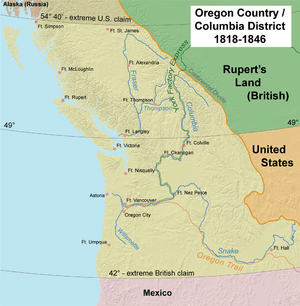

A Look Back: The Oregon Country

The Pacific Northwest was a wild and distant place in the early 1800s. During the War of 1812, two fur trading companies were active there. One was the Canadian North West Company (NWC), and the other was the American Pacific Fur Company (PFC).

The American company, the PFC, was in a tough spot when news of the war arrived. A British warship was on its way! In 1813, the PFC decided to sell its business to the NWC. When the British warship arrived, the American Fort Astoria was renamed Fort George to honor the British King.

After the war, Britain and the United States tried to decide on a border for this region. In 1818, they signed the Treaty of 1818. This treaty said that people from both nations could freely use the resources of the Pacific Northwest. The goal was to "prevent disputes" between the two countries.

In the years that followed, the North West Company grew. But they had many fights with their main rival, the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC). These fights were sometimes called the Pemmican War. In 1821, the British government made the NWC merge with the HBC. This meant the HBC became even more powerful.

Border Talks Continue

Through 1825 and 1826, British officials kept offering ideas for dividing the Pacific Coast. These ideas often came from the fur trading companies. They suggested extending the border west along the 49th parallel to the Rocky Mountains. Then, the Columbia River would become the border until it reached the Pacific Ocean.

However, the United States wanted the border to follow the 49th parallel all the way to the Pacific Ocean. The two sides could not agree. So, they decided to put off a final decision about the border for a while longer.

Building Fort Vancouver

Fort Vancouver was built on the north bank of the Columbia River in the winter of 1824–1825. The Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) in London decided to build it. They wanted it to be the main office for their fur trade in the Columbia District.

Before this, the main office was at Fort George. But Sir George Simpson, a leader of the HBC, thought Fort George was not in a good spot. He believed that the border between Britain and the US would eventually be set along the Columbia River. So, he chose a new location for the fort. This spot was across from the mouth of the Willamette River. It was an open, fertile area, safe from floods, and easy to reach from the Columbia River.

Inside the Fort

What Fort Vancouver Looked Like

Fort Vancouver was a large and strong place. It was shaped like a rectangle, about 250 yards long and 150 yards wide. A tall wooden wall, made of strong pickets (large beams), surrounded it. This wall was 20 feet high and very secure.

At each corner of the fort, there was a bastion (a small tower) with cannons. Inside the fort, there were about 40 neat wooden buildings. These buildings were used for many different things. They included homes, warehouses, a school, a library, a pharmacy, a chapel, and a blacksmith shop. There was also a large factory for making goods.

The Chief Factor's house was in the center of the fort and had two stories. Important people like company clerks, traders, and doctors ate their meals there. Regular workers and fur trappers usually could not eat in the Chief Factor's house. After dinner, many of these gentlemen would go to the "Bachelor's Hall." There, they could relax, smoke, read, or share stories of their adventures. One person remembered that the smoking room looked like a museum, filled with weapons, clothes, and interesting items from different cultures.

Outside the fort's walls, there were more buildings. There were also fields, gardens, fruit orchards, a shipyard, and places for making things like leather and lumber. By 1843, about 60 wooden houses stood outside the fort, roughly 600 yards away. This small village was home to fur trappers, workers, and their families. Many of these families included Indigenous peoples or Métis (people of mixed European and Indigenous heritage).

The village was often called Kanaka Village. This was because many Hawaiians worked for the company and lived there. In fact, Fort Vancouver had the largest group of Hawaiians living outside their home islands at that time.

How the Fur Trade Worked

In the early 1800s, people in Europe really wanted textiles made from fur. This led the HBC to expand its North American fur trade all the way to the Pacific Northwest. Fort Vancouver became the main office for the HBC's fur trade in the Columbia District. This area stretched from the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Ocean. It went from Sitka in the north to San Francisco in the south.

Fur trappers would bring the animal pelts they collected to the fort. They traded these furs for company credit, which they could use to buy goods in the fort's shops. Furs from smaller HBC outposts were brought to Fort Vancouver by land or by boat on the Columbia River.

Once at the fort, clerks would sort and count the furs. Then, the furs were hung to dry in a large two-story storehouse. After drying, they were mixed, weighed into 270-pound bundles, and packed with tobacco leaves to keep insects away. These large bundles were pressed and wrapped in elk or bear hides. Finally, the 270-pound fur bales were loaded onto boats on the Columbia River. They were shipped to London through HBC trade routes. In London, the furs were sold to companies that made textiles. Many hat makers bought beaver furs to create popular beaver felt hats.

The People of Fort Vancouver

For most of its history, Fort Vancouver was the largest non-Indigenous settlement in the Pacific Northwest. Many different cultures lived and worked there. The population included French Canadians, Métis, and Kanaka Hawaiians. There were also English, Scots, Irish, and various Indigenous peoples like Iroquois and Cree.

The most common language spoken at the fort was Canadian French. Company records and official journals were kept in English. However, when trading with the local communities, people often used Chinook Jargon. This was a mix of Chinook, Nootka, Chehalis, English, French, Hawaiian, and other languages.

In 1846, a count of the people at Fort Vancouver showed how diverse it was. There were 57 men from the Hebrides, Orkney, and Shetland Islands. This was the same number as all the workers from England and mainland Scotland combined. There were 91 men from Upper Canada, Lower Canada, and Rupert's Land. These men came from English, French Canadian, Métis, Iroquois, and Cree backgrounds. But the largest group was the Kanaka Hawaiians, with 154 people. They made up 43% of everyone at the fort that year!

Chief Factor Dr. John McLoughlin was the first manager of Fort Vancouver. He held this important job for almost 22 years, from 1824 to 1845. McLoughlin made sure British laws were followed and kept peace with the local native groups. He also tried to keep order with American settlers. McLoughlin later became known as the Father of Oregon. This was because he helped American settlers, even though the company did not want them to settle south of the Columbia River. He left the company in 1846 and helped found Oregon City.

James Douglas also spent 19 years at Fort Vancouver. He started as a clerk and was promoted to Chief Trader in 1834. From 1839 to 1845, he was a Chief Factor alongside McLoughlin. Douglas also helped set up other HBC trading posts.

Growing Food at the Fort

When Fort Vancouver was first built, Governor George Simpson wanted it to grow its own food. Shipping food was very expensive. The fort usually kept a year's worth of extra supplies in its warehouses. This helped them avoid problems if ships were lost or other disasters happened.

Soon, Fort Vancouver started producing more food than it needed. Some of this extra food was sent to other HBC posts. The area around the fort was known as "La Jolie Prairie" (the pretty prairie). Over time, Fort Vancouver began to do more than just trade furs. It started selling farm products, salmon, lumber, and other goods. They sold these items to places like Russian America, the Hawaiian Kingdom, and Mexican California. The HBC even opened offices in Sitka, Honolulu, and Yerba Buena (San Francisco) to help with this trade.

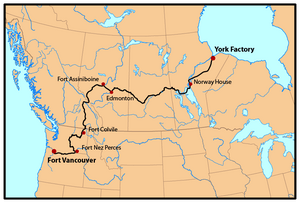

The York Factory Express

Fort Vancouver received some of its supplies through a long overland route called the York Factory Express. This route was first used by the NWC. Each spring, two groups of travelers, called brigades, were sent out. One started from Fort Vancouver, and the other from York Factory far to the east.

A typical brigade had about 40 to 75 men. They carried supplies, furs, and letters by boat, horseback, and in backpacks. They stopped at various HBC posts along the way. Furs stored at York Factory were then sold in London at a yearly fur sale. Along the route, Indigenous peoples were often paid with trade goods to help the brigades carry their loads around waterfalls and dangerous rapids.

American Settlers Arrive

The HBC controlled the fur trade in much of the Oregon Country. They did not want settlers to come, because it made the fur trade harder. But by 1838, American settlers started crossing the Rocky Mountains. More and more came each year. Many left from St. Louis, Missouri, and followed a difficult path called the Oregon Trail. For many of these settlers, Fort Vancouver was the last stop on the Oregon Trail. They could get supplies there before finding land to build their homes.

In 1843, during what was called the Great Migration of 1843, about 700 to 1,000 American settlers arrived via the Oregon Trail.

The Oregon Treaty

In 1846, the Oregon Treaty was signed. This treaty set the border between Canada and the United States at the 49th parallel north. This meant Fort Vancouver was now in American territory.

The treaty said the HBC could keep operating and use the Strait of Juan de Fuca, Puget Sound, and the Columbia River. However, the treaty made it very hard for the company to do business. Operations became unprofitable, and Fort Vancouver soon closed down.

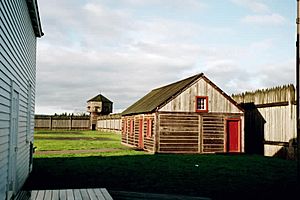

Bringing the Fort Back to Life

Because Fort Vancouver was so important in United States history, a plan was made to save the site. On June 19, 1948, Fort Vancouver was named a US National Monument. Then, on June 30, 1961, it became the Fort Vancouver National Historic Site.

In 1996, an even larger area was protected. A 366-acre area around the fort, including Kanaka Village, the Columbia Barracks, and the riverbank, became the Vancouver National Historic Reserve. The National Park Service takes care of it.

You can visit the fort today! Some of the reconstructed buildings you can tour include a bake house, where you can see how hardtack (a type of biscuit) was made. There's also a blacksmith shop, a carpenter shop with old tools, and the kitchen, where daily meals were prepared.

See also