Russian America facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Russian America

Русская Америка

Russkaya Amerika |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colony of the Russian Empire | |||||||||

| 1799–1867 | |||||||||

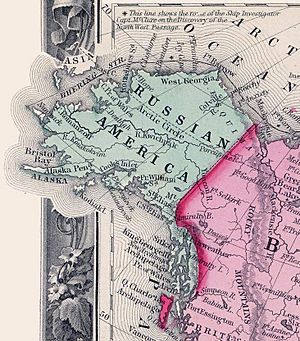

Russian America in 1860 |

|||||||||

| Capital | Kodiak (1799–1804) Novo-Arkhangelsk |

||||||||

| Government | |||||||||

| Governor | |||||||||

|

• 1799–1818 (first)

|

Alexander Andreyevich Baranov | ||||||||

|

• 1863–1867 (last)

|

Dmitry Petrovich Maksutov | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

| 8 July 1799 | |||||||||

| 18 October 1867 | |||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Today part of | United States | ||||||||

| a. ^ The Russian-American Company was chartered by the Emperor in 1799, to govern Russian possessions in North America on behalf of the Russian Empire. | |||||||||

|

| History of Alaska |

|---|

| Prehistory |

| Russian America (1733–1867) |

| Department of Alaska (1867–1884) |

| District of Alaska (1884–1912) |

| Territory of Alaska (1912–1959) |

| State of Alaska (1959–present) |

| Other topics |

Russian America (Russian: Русская Америка, romanized: Russkaya Amerika) was the name for the lands in North America that belonged to the Russian Empire. This was from 1799 to 1867. Most of this land is now Alaska in the United States.

It also included small outposts in California, like Fort Ross. There were even three forts in Hawaii, including Russian Fort Elizabeth. The main settlements were in Alaska. The capital was Novo-Arkhangelsk, which is now Sitka.

Russia first landed in Alaska in the mid-1700s. In 1799, Russia officially claimed the territory. They gave special rights to a company called the Russian-American Company. This company was supported by the government. The Russian Orthodox Church also became important in the area.

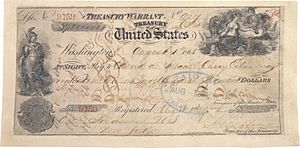

The colony first grew rich from the fur trade. But by the mid-1800s, too much hunting and problems with supplies caused it to decline. Most settlements were left empty by the 1860s. Russia then sold its last lands to the United States in 1867. The price was $7.2 million, which is about $127 million today.

Contents

How Russia First Saw Alaska

In 1648, a man named Semyon Dezhnev sailed from the Kolyma River. He went through the Arctic Ocean and around the eastern tip of Asia. Some stories say that some of his boats were blown off course and reached Alaska. But there is no proof that anyone settled there. Dezhnev's discovery was not shared with the government. So, people still wondered if Siberia was connected to North America.

In 1725, Emperor Peter the Great asked for another expedition. As part of the Second Kamchatka expedition (1733–1743), two ships set sail in June 1741. The Sv. Petr was led by Vitus Bering, and the Sv. Pavel by Aleksei Chirikov. They sailed from Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky on the Kamchatka Peninsula.

The two ships soon got separated. But both kept sailing east. On July 15, Chirikov saw land. It was likely the west side of Prince of Wales Island in southeast Alaska. He sent a group of men ashore. They were the first Europeans to land on the northwestern coast of North America.

Around July 16, Bering and his crew saw Mount Saint Elias on the Alaskan mainland. They soon turned back towards Russia. Chirikov and the Sv. Pavel returned to Russia in October. They brought news of the land they had found.

In November, Bering's ship was wrecked on Bering Island. Bering became sick and died there. High winds broke the Sv. Petr into pieces. The remaining crew spent the winter on the island. In August 1742, the survivors built a new boat from the wreckage. They sailed back to Russia. Bering's crew reached Kamchatka in 1742. They brought back news of the expedition. The high quality of the sea-otter furs they found made Russians want to settle in Alaska.

Russian Settlement in Alaska

Early Colonization (1740s to 1800)

Starting in 1743, small groups of fur traders began sailing from Russia to the Aleutian Islands. These trips became longer, lasting two to four years or more. The crews set up hunting and trading posts. By the late 1790s, some of these became permanent settlements. About half of the fur traders were from Europe, and the others were from Siberia or had mixed backgrounds.

The Russian promyshlenniki (fur traders) did not hunt the marine animals themselves. Instead, they forced the Aleuts to do the work. They often took family members hostage to make the Aleuts hunt for seal furs. This way of colonial exploitation was similar to how Russians expanded into Siberia.

As news of the rich furs spread, competition among Russian companies grew. Many Aleuts were also forced into slavery. Catherine the Great, who became Empress in 1763, said she wanted to treat the Aleuts well. She urged her people to be fair. On some islands, traders lived peacefully with the local people. But other groups were violent. They took hostages, split up families, and forced people to leave their villages.

The growing competition between trading companies led to more conflicts. These made relations with the native people worse. As animal populations went down, the Aleuts had to take bigger risks. They depended on the Russian fur trade for their survival. The Shelikhov-Golikov Company used violence to control the native people. When the Aleuts fought back, the Russians killed many. They also destroyed their boats and hunting tools. This left the Aleuts with no way to survive.

The worst impact came from diseases. During the first two generations of Russian contact (1741-1799), 80 percent of the Aleut population died. These were from European infectious diseases. Europeans had immunity to them, but the Aleut people did not.

The Alaskan colony was not very profitable because of high transportation costs. But most Russian traders wanted to keep the land. In 1784, Grigory Shelikhov arrived at Three Saints Bay on Kodiak Island. He later started the Russian-American Company. The Koniag Alaska Natives bothered the Russian group. Shelikhov responded by killing hundreds and taking hostages. This made the rest obey him.

After gaining control of Kodiak Island, Shelikhov founded the second permanent Russian settlement in Alaska. It was at Three Saints Bay. The first permanent settlement was Unalaska, settled in 1774.

In 1790, Shelikhov hired Alexander Andreyevich Baranov to manage his fur business in Alaska. Baranov moved the colony to the northeast end of Kodiak Island. There was more timber available there. This site later became the city of Kodiak. Russian colonists married Koniag women and started families. Their last names, like Panamaroff and Petrikoff, are still around today.

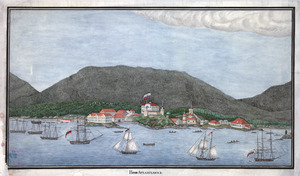

In 1795, Baranov was worried about other Europeans trading with natives in southeast Alaska. He set up Mikhailovsk near present-day Sitka. He bought the land from the Tlingit people. But in 1802, while Baranov was away, Tlingit from a nearby village attacked and destroyed Mikhailovsk. Baranov returned with a Russian warship and destroyed the Tlingit village. He built a new settlement called New Archangel (Russian: Ново-Архангельск, romanized: Novo-Arkhangelsk) on the ruins. It became the capital of Russian America, and later the city of Sitka.

As Baranov secured Russian settlements, the Shelikhov family worked to get a monopoly on Alaska's fur trade. In 1799, Shelikhov's son-in-law, Nikolay Petrovich Rezanov, got a monopoly from Emperor Paul I. Rezanov formed the Russian-American Company. The Emperor expected the company to build new settlements and expand colonization.

Later Colonization (1800 to 1867)

By 1804, Baranov was the manager of the Russian–American Company. He had strengthened the company's control over the fur trade. He did this after defeating the local Tlingit group at the Battle of Sitka. The Russians never fully colonized Alaska. They mostly stayed along the coast and did not go far inland.

From 1812 to 1841, the Russians operated Fort Ross, California. From 1814 to 1817, Russian Fort Elizabeth was active in the Kingdom of Hawaii. By the 1830s, the Russian monopoly on trade was getting weaker. The British Hudson's Bay Company leased the southern part of Russian America in 1839. This was under the RAC-HBC Agreement. They set up Fort Stikine, which started taking away trade from the Russians.

A company ship visited the Russian American outposts only every two or three years. This meant supplies were limited. Trading was not as important as trapping operations done by Aleutian workers. This made the Russian outposts rely on British and American merchants for food and materials. Baranov knew that the Russian-American Company could not survive without trading with foreigners. Ties with Americans were helpful because they could sell furs in Guangzhou, which was closed to Russians at the time. The problem was that American hunters and trappers started entering lands the Russians considered theirs.

Several Russian-American Company ships sank or were damaged in storms. This left the outposts with very few resources. On June 24, 1800, an American ship sailed to Kodiak Island. Baranov arranged to buy over 12,000 rubles worth of goods from the ship. This prevented "immediate starvation." During his time, Baranov traded over 2 million rubles worth of furs for American supplies. This worried the company's directors. From 1806 to 1818, Baranov sent 15 million rubles worth of furs to Russia. But he only received less than 3 million rubles in supplies. This was barely half of the money spent just on the company office in Saint Petersburg.

The Russo-American Treaty of 1824 said that Russia had exclusive rights to the fur trade north of latitude 54°40'N. American rights were limited to below that line. This division was repeated in the Treaty of Saint Petersburg in 1825. This agreement also set most of the border with British North America. However, these agreements were soon ignored. When Alexandr Baranov retired in 1818, Russia's hold on Alaska became even weaker.

When the Russian-American Company's charter was renewed in 1821, it said that chief managers had to be naval officers. Most naval officers had no experience in the fur trade, so the company suffered. The new charter also tried to stop all contact with foreigners, especially the competing Americans. This plan did not work well. The Russian colony had become used to relying on American supply ships. The United States had also become a valuable customer for furs. Eventually, the Russian–American Company made an agreement with the Hudson's Bay Company. This gave the British rights to sail through Russian territory.

Russian Settlements in North America

- Unalaska, Alaska – 1774

- Three Saints Bay, Alaska – 1784

- Fort St. George in Kasilof, Alaska – 1786

- St. Paul, Alaska – 1788

- Fort St. Nicholas in Kenai, Alaska – 1791

- Pavlovskaya, Alaska (now Kodiak) – 1791

- Fort Saints Constantine and Helen on Nuchek Island, Alaska – 1793

- Fort on Hinchinbrook Island, Alaska – 1793

- New Russia near present-day Yakutat, Alaska – 1796

- Redoubt St. Archangel Michael, Alaska near Sitka – 1799

- Novo-Arkhangelsk, Alaska (now Sitka) – 1804

- Fort Ross, California – 1812

- Fort Elizabeth near Waimea, Kaua'i, Hawai'i – 1817

- Fort Alexander near Hanalei, Kaua'i, Hawai'i – 1817

- Fort Barclay-de-Tolly near Hanalei, Kaua'i, Hawai'i – 1817

- Fort (New) Alexandrovsk at Bristol Bay, Alaska – 1819

- Redoubt St. Michael, Alaska – 1833

- Nulato, Alaska – 1834

- Redoubt St. Dionysius in present-day Wrangell, Alaska (now Fort Stikine) – 1834

- Pokrovskaya Mission, Alaska – 1837

- Kolmakov Redoubt, Alaska – 1844

Missionary Work and the Russian Orthodox Church

At Three Saints Bay, Shelikhov built a school. It taught native people to read and write Russian. He also brought the first missionaries and clergymen. They spread the Russian Orthodox faith. This faith had been introduced informally earlier. Some fur traders started families with local people. Others adopted Aleut trade partners as godchildren. This helped them gain loyalty.

The missionaries soon spoke out against the exploitation of native people. Their reports show the violence used to establish colonial rule. The Russian-American Company's monopoly was continued by Emperor Alexander I in 1821. But the company had to financially support missionary efforts. The company board ordered chief manager Etholén to build a home in New Archangel for bishop Veniaminov.

When a Lutheran church was planned for the Finnish people in New Archangel, Veniaminov stopped Lutheran priests from trying to convert Tlingits. Veniaminov found it hard to influence the Tlingit people outside New Archangel. This was because they were politically independent from the Russian-American Company. So, they were less open to Russian culture than the Aleuts. A smallpox epidemic spread across Alaska from 1835-1837. The medical help given by Veniaminov led to many conversions to Orthodoxy.

Missionaries in Russian America valued local cultures. They encouraged native leadership in church life and missionary work. Compared to later Protestant missionaries, the Orthodox policies were more sensitive to native Alaskan cultures. This cultural policy aimed to gain the loyalty of the native people. It showed that the Church and State protected the more than 10,000 inhabitants of Russian America. The number of ethnic Russian settlers was always small, less than 812. Most were in Sitka and Kodiak.

It was hard to train Russian priests to speak the different Alaskan Indigenous languages. To fix this, Veniaminov opened a seminary in 1845. It was for mixed-race and native candidates for the Church. Good students were sent to schools in Saint Petersburg or Irkutsk. The Holy Synod ordered four missionary schools to open in 1841. They were in Amlia, Chiniak, Kenai, and Nushagak. Veniaminov created the lessons. They included Russian history, reading, math, and religious studies.

One result of the missionary work was a new, independent native identity. Many native traditions survived within the local "Russian" Orthodox tradition. This is still seen in the religious life of the villages. Part of this modern native identity is an alphabet. It also formed the basis for written literature in almost all ethnic-linguistic groups in southern Alaska. Father Ivan Veniaminov (later St. Innocent of Alaska) was famous in Russian America. He created an Aleut dictionary based on the Russian alphabet.

Today, the most visible sign of the Russian colonial period in Alaska is the nearly 90 Russian Orthodox churches. They have over 20,000 members, almost all of whom are indigenous people. These include several Athabascan groups, many Yup'ik communities, and almost all Aleut and Alutiiq populations. Among the few Tlingit Orthodox churches, the large group in Juneau adopted Orthodox Christianity after the Russian colonial period. This was in an area where there had been no Russian settlers or missionaries. The widespread and ongoing local Russian Orthodox practices likely come from a mix of local beliefs with Christianity.

Before Alaska was sold, there were 400 native converts to Orthodoxy in New Archangel. The number of Tlingit followers went down after Russian rule ended. By 1882, there were only 117 followers in Sitka.

Sale of Alaska to the United States

By the 1860s, the Russian government was ready to give up its colony in Russian America. Too much hunting had greatly reduced the number of fur-bearing animals. Competition from the British and Americans made the situation worse. Also, it was hard to supply and protect such a distant colony. These reasons made Russia less interested in the territory.

After Russian America was sold to the U.S. in 1867, all the properties of the Russian–American Company were sold off. The price was $7.2 million (about 2 cents per acre).

After the sale, many elders of the local Tlingit tribe said that "Castle Hill" was the only land Russia had the right to sell. Other native groups also argued that they had never given up their land. They said the Americans came onto their land and took it. Native land claims were not fully addressed until the late 1900s. This happened with the signing of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act.

At its peak, the Russian population in Russian America was 700. This was compared to 40,000 Aleuts. The Aleuts and Creoles were promised the rights of U.S. citizens. They had three years to become citizens, but few chose to do so. General Jefferson C. Davis ordered the Russians out of their homes in Sitka. He said the homes were needed for the Americans. Many Russians went back to Russia. Others moved to the Pacific Northwest and California.

|

|

| History of Alaska |

|---|

| Prehistory |

| Russian America (1733–1867) |

| Department of Alaska (1867–1884) |

| District of Alaska (1884–1912) |

| Territory of Alaska (1912–1959) |

| State of Alaska (1959–present) |

| Other topics |

See also

In Spanish: Colonización rusa de América para niños

In Spanish: Colonización rusa de América para niños

| Bessie Coleman |

| Spann Watson |

| Jill E. Brown |

| Sherman W. White |