North American fur trade facts for kids

The North American fur trade was a huge business where people bought and sold animal furs in North America. Long before Europeans arrived, different Native American groups traded furs with each other. When Europeans came, they joined this trade, sending furs back to Europe.

Merchants from France, England, and the Dutch Republic built trading posts and forts across North America. They traded with local Native American tribes. This trade became super important in the 1800s, with big networks connecting many places.

The fur trade quickly became a main way to make money in North America. European countries fought over who would control it. The United States also wanted to reduce British control over the trade after it became a country. Many Native American groups started to rely on the fur trade for their income and for goods made in Europe.

However, by the mid-1800s, European fashion changed, and people didn't want furs as much. This caused fur prices to drop, and many fur companies closed. Many Native American groups became poor and lost their power.

The hunting of beavers for their fur was very bad for beaver populations. The natural ecosystems that needed beavers for dams and water were also badly damaged. This led to environmental problems and even dry areas. Sadly, beaver populations in North America were almost wiped out.

Contents

How the Fur Trade Started

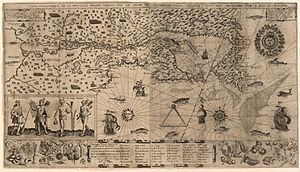

The French explorer Jacques Cartier made three trips to the Gulf of Saint Lawrence in the 1530s and 1540s. He did some of the first fur trading between Europeans and First Nations people. Cartier mostly traded for furs used as decoration. He didn't realize how important the beaver pelt would become. Beaver fur later became very popular in Europe for making hats.

The first European trading for beaver pelts happened because of the growing cod fishing industry in the 1500s. Fishermen, mostly from Basque country, fished near Newfoundland. They dried their fish to take back to Europe. They needed safe harbors with lots of wood to dry the fish. This led to their first meetings with local Native Americans, and they started simple trading.

The fishermen traded metal items for beaver robes. These robes were made of beaver pelts sewn together and tanned by Native Americans. The fishermen used them to stay warm on their long trips across the Atlantic. These castor gras (fat beavers) became very valuable to European hat makers in the late 1500s. They used the pelts to make felt. When people discovered how good beaver fur was for felt, and beaver felt hats became popular, the small trade by fishermen grew into a huge business. This happened first in French areas, then in British areas in the 1600s.

New France in the 1600s

The fur trade changed from a seasonal coastal trade to a permanent inland business. This change officially began when Samuel de Champlain founded Quebec in 1608. This started the settlement of New France. French traders began moving west from Tadoussac, up the Saint Lawrence River, and into the "upper country" around the Great Lakes. In the first half of the 1600s, both the French and Native American groups made smart moves to help their own money and power.

Champlain led this expansion and brought French efforts together. Native peoples were the main suppliers in the fur trade. Champlain quickly made friends with the Algonquin, Montagnais, and most importantly, the Huron to the west. The Huron people acted as middlemen, trading between the French and other nations further inland. Champlain helped the northern groups in their fights against the Iroquois Confederacy to the south. He secured the Ottawa River route to Georgian Bay, which greatly expanded the trade. Champlain also sent young French men, like Étienne Brûlé, to live with Native Americans. They learned the land, language, and customs, and helped with trade.

Champlain also changed how the trade was run. He created the first informal business group in 1613 to deal with growing losses from competition. This group later became official with a royal charter. This led to a series of trade monopolies during the time of New France. The most famous monopoly was the Company of One Hundred Associates in France. While these monopolies controlled the trade, they also had to pay money to the government, pay for military costs, and encourage people to settle in New France.

The huge wealth from the fur trade caused problems with enforcing the monopoly. Independent traders, known as coureurs des bois (or "runners of the woods"), started trading without permission in the late 1600s and early 1700s. Many Métis people, who were descendants of French traders and Native American women, joined this independent trade. The use of money and the importance of personal connections helped independent traders more than the big monopolies. The new English colonies to the south quickly joined the profitable trade. They even attacked the Saint Lawrence River valley and controlled Quebec from 1629 to 1632.

While the fur trade brought wealth to some French traders, it also brought big changes to Native American groups along the Saint Lawrence River. European goods like iron axe heads, brass kettles, cloth, and firearms were bought with beaver pelts and other furs. The hunting of beavers in the Saint Lawrence area led to fierce competition between the Iroquois and Huron. They both wanted access to the rich fur lands of the Canadian Shield.

The competition for hunting is thought to have led to the destruction of the St. Lawrence Iroquoians by 1600. This was likely done by the Iroquois Mohawk tribe, who were closest to them and had the most to gain.

The Iroquois got firearms from Dutch and later English traders along the Hudson River. This led to more deaths in their wars. New diseases brought by the French also greatly reduced Native American populations and broke up their communities. Along with warfare, disease almost destroyed the Huron people by 1650.

Competition Between France and England

The Beaver Wars

In the 1640s and 1650s, the Beaver Wars started by the Iroquois caused many Native Americans to move. They fled the violence and sought safety west and north of Lake Michigan. The Five Nations of the Iroquois wanted to be the only ones trading furs between Europeans and other Native Americans. They worked to remove rivals like the Huron (Wendat).

By the 1620s, the Iroquois needed iron tools. They got these by trading furs with the Dutch at Fort Nassau (now Albany, New York). Between 1624 and 1628, the Iroquois pushed out their neighbors, the Mahican. This allowed them to be the only group in the Hudson River valley trading with the Dutch. By 1640, the Five Nations had hunted most of the beavers in their homeland. Also, their beavers didn't have the thick pelts Europeans wanted most. These better pelts were found further north in what is now northern Canada.

The Five Nations started the "Beaver Wars" to control the fur trade from other middlemen. The Wendat homeland was in what is now southern Ontario. Through Wendake, the Ojibwe and Cree from further north traded with the French. In 1649, the Iroquois attacked Wendake. They aimed to destroy the Wendat people, taking thousands of Wendat to be adopted by Iroquois families. The rest were killed. The Iroquois population had been greatly reduced by European diseases like smallpox, as they had no immunity.

The Iroquois had already fought the French in 1609, 1610, and 1615. But the "Beaver Wars" led to a long struggle with the French. The French did not want the Five Nations to be the only fur trade middlemen. At first, the French did not do well. The Iroquois caused more losses than they suffered. French settlements were often cut off, and canoes carrying furs to Montreal were stopped. Sometimes the Iroquois even blocked the Saint Lawrence River.

New France Under the King

New France was run by a company called the Compagnie des Cent-Associés. This company went bankrupt in 1663 because the Iroquois attacks made the fur trade unprofitable for the French. After the company failed, King Louis XIV took over New France as a royal colony. He wanted his new colony to make money. So, he sent the Carignan-Salières Regiment to defend it.

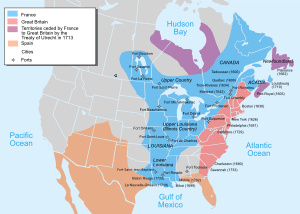

In 1666, the Carignan-Salières Regiment attacked the Iroquois homeland. This led the Five Nations to make peace in 1667. From about 1660 to 1763, France and Great Britain had a strong rivalry. Each European power tried to expand its fur-trading areas. The two empires and their Native American allies fought in conflicts that ended with the French and Indian War. This war was part of the Seven Years' War in Europe.

In 1659–1660, French traders Pierre-Esprit Radisson and Médard Chouart des Groseilliers traveled north and west of Lake Superior. This trip started a new era of expansion. Their trading trip brought in a lot of furs. More importantly, they learned about a frozen sea to the north that offered easy access to the fur-rich interior. When they returned, French officials took their furs because they were unlicensed traders. Radisson and Groseilliers then went to Boston and London. They got money and two ships to explore the Hudson Bay. Their success led England to create the Hudson's Bay Company in 1670. This company became a major player in the fur trade for the next two centuries.

Moving Westward

French exploration and expansion westward continued. Men like La Salle and Jacques Marquette explored and claimed the Great Lakes, as well as the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys. To strengthen these claims, the French built a series of small forts. The first was Fort Frontenac on Lake Ontario in 1673. With the building of Le Griffon in 1679, the first large sailing ship on the Great Lakes, these forts opened the upper Great Lakes to French ships.

More Native American groups learned about European goods and became trading middlemen, especially the Ottawa. The competition from the new English Hudson's Bay Company trade was felt as early as 1671. French profits decreased, and the role of Native American middlemen changed. This new competition made the French expand into the North West to win back Native American customers.

What followed was a constant expansion north and west of Lake Superior. The French used talks with Native Americans to win back trade. They also used military force to temporarily remove the Hudson's Bay Company competition. At the same time, the English presence in New England grew stronger. The French were busy trying to stop coureurs de bois and allied Native Americans from smuggling furs to the English. The English often offered higher prices and better goods.

In 1675, the Iroquois made peace with the Machian and finally defeated the Susquenhannock. In the late 1670s and early 1680s, the Five Nations began raiding what is now the Midwest. They fought the Miami and the Illinois. They also fought against and tried to make alliances with the Ottawa. One Onondaga chief, Otreouti, said in 1684 that the wars against the Illinois and Miami were fair because "They came to hunt beavers on our lands..."

The French and Indian War

At first, the French were unsure about the Iroquois moving west. On one hand, having the Five Nations at war with other nations stopped those nations from trading with the English at Albany. On the other hand, the French didn't want the Iroquois to become the only middlemen in the fur trade. But as the Iroquois kept winning against other nations, they stopped French and Algonquin fur traders from entering the Mississippi River valley. The Ottawa also showed signs of making an alliance with the Five Nations. So, in 1684, the French declared war on the Iroquois.

Starting in 1684, the French repeatedly attacked the Iroquois homeland. They burned crops and villages. King Louis XIV wanted to "humble" the Five Nations and teach them to respect France. These repeated French attacks took a toll. The Mohawk, who had about 300 warriors in the 1670s, had only 170 warriors by the summer of 1691. The Iroquois fought back by raiding New France. Their most successful raid was on Lachine in 1689. But the French government's greater resources slowly wore them down until they finally made peace in 1701.

The settlement of Native American refugees from the Beaver Wars in the western and northern Great Lakes, along with the decline of the Ottawa middlemen, created huge new markets for French traders. Renewed Iroquois warfare in the 1680s also boosted the fur trade, as Native American allies of the French bought weapons. The new, more distant markets and strong English competition made direct trade from the North West to Montreal difficult. The old system of Native American middlemen and coureurs de bois traveling to trade fairs in Montreal or illegally to English markets was replaced by a more complex trade network.

Licensed voyageurs, working with Montreal merchants, used water routes to reach distant parts of the North West. They carried trade goods in canoes. These risky trips needed large initial investments and took a long time to make money. The first money from fur sales in Europe didn't arrive until four or more years after the first investment. These economic factors meant that only a few large Montreal merchants with enough money could control the fur trade. This trend grew in the 1700s and reached its peak with the big fur-trading companies of the 1800s.

Impact on Beaver Populations

The competition between the English and the French was terrible for beaver populations. Beavers went from being a source of food and clothing for Native Americans to a key item for trade with Europeans. The French constantly looked for cheaper fur and tried to cut out Native American middlemen. This led them to explore deep into the interior, all the way to Lake Winnipeg and the Central Plains.

While some historians disagree, many believe that Native American hunters over-hunted beavers to supply the global fur markets. They didn't think about the possibility of beavers disappearing. As competition grew between the English and French in the 1600s, Native American tribes were still the main fur harvesters and middlemen. This increased competition led to a severe over-hunting of beavers. Data from three Hudson's Bay Company trading posts show this trend.

The English and French had different ways of organizing trade. The Hudson's Bay Company had a monopoly on beaver trade in the Hudson Bay area. The French used licenses to rent out their trading posts. This encouraged French traders to expand their reach. French traders went into much of the Great Lakes region. They set up posts on Lake Winnipeg, Lac des Praires, and Lake Nipigon. This was a serious threat to the flow of furs to the York Factory. More trading posts near English areas meant Native Americans had more places to sell their goods.

Studies of beaver populations around trading posts consider the number of beavers traded, beaver biology, and old estimates of beaver numbers. Most experts agree that Native Americans were the main ones who depleted animal stocks.

The main effect of increased French competition was that the English paid higher prices to Native Americans for furs. This gave Native Americans more reason to hunt more beavers. When prices went up, hunters brought in more furs. Data from trading posts show that Native American fur supply was sensitive to price. Also, no single tribe had complete control over trade in any area. Most tribes competed with each other to get the most benefit from the English and French presence.

Also, the "tragedy of the commons" was clear here. When resources are open to everyone, there's no reason to save them. Tribes that tried to save resources lost out compared to others who hunted as much as possible. So, it seemed that First Nations tribes didn't worry much about the fur trade lasting. The problem of over-hunting was made worse because the French tried to remove middlemen like the Huron. All these factors led to an unsustainable fur trade that quickly reduced beaver populations.

A study by Ann M. Carlos and Frank D. Lewis shows that beaver populations dropped to a lower stable level. Further declines were caused by over-hunting at two of the three English trading posts (Albany and York). The data from the third trading post, Fort Churchill, is interesting. This post was not under French pressure. So, it didn't have the same over-hunting. At Fort Churchill, beaver numbers adjusted to a healthy level. The Churchill data further supports the idea that French-English competition caused over-hunting.

Impact on Native American People

Changes in Lifestyle

Native American beliefs often focused on respecting nature. Many tribes had rules about hunting, especially against killing deer unnecessarily. There were rules against taking the skins of unhealthy deer. But the profitable deerskin trade made hunters go beyond these old rules. The hunting economy collapsed because deer were over-hunted and lost their lands to settlers. As deer numbers dropped and the government pushed tribes to live like European settlers, raising animals replaced deer hunting for food and income.

Native Americans became dependent on manufactured goods like guns and farm animals. They lost many of their traditional ways. With new cattle herds on hunting lands and more focus on farming (due to the cotton gin), Native Americans struggled to keep their place in the economy. Some hunters became more successful than others, creating differences within tribes.

Traders often treated an individual's debt as debt for the whole tribe. They used tricks to keep Native Americans in debt. Traders would cheat with the weighing system for deerskins. They would also tamper with manufactured goods to make them seem less valuable. To get enough deerskins, many men in the tribes stopped their traditional seasonal roles and became full-time traders. When the deerskin trade collapsed, Native Americans depended on manufactured goods. They couldn't go back to their old ways because they had lost knowledge.

The Role of Women

Marriage as a Trading Strategy

Almost all Native American communities encouraged fur traders to marry Native American women. This helped build long-term relationships. It ensured a steady supply of European goods for their communities. It also stopped fur traders from dealing with other tribes. The fur trade often involved a credit system. A fur trader would arrive in summer or fall, give goods to Native Americans, and they would pay him back in the spring with furs from animals they hunted over winter.

Fur traders found that marrying the daughters of chiefs helped ensure cooperation from the whole community. Marriage alliances were also made between Native American tribes. In 1679, French diplomat Daniel Greysolon, Sieur du Lhut held a peace meeting at Fond du Lac (now Duluth, Minnesota). Leaders from the Ojibwe, Dakota, and Assiniboine attended. They agreed that the daughters and sons of chiefs would marry each other to promote peace and ensure French goods flowed into the region.

The French fur trader Claude-Charles Le Roy wrote that the Dakota decided to make peace with their traditional enemies, the Ojibwe. This was to get French goods that the Ojibwe were blocking. Le Roy wrote the Dakota "could obtain French merchandise only through the agency of the Sauteurs [Ojibwe]". So they made "a treaty of peace by which they were mutually bound to give their daughters in marriage on both sides". Native American marriages usually involved a simple ceremony with valuable gifts exchanged between the parents. Unlike European marriages, they could be ended at any time by one partner leaving.

Native Americans were organized into family and clan networks. Marrying a woman from one of these networks made a fur trader part of that network. This meant that Native Americans in that clan were more likely to trade only with him. Also, fur traders found that Native Americans were more likely to share food, especially in winter, with traders who were seen as part of their communities.

One fur trader who married an Ojibwe girl wrote in his diary about his "secret satisfaction at being compelled to marry for my safety." On the other hand, a fur trader was expected to favor the clan he married into with European goods. If he didn't, his reputation would be ruined. The Ojibwe, like other tribes, believed all life was based on giving and receiving. They left "gifts" of tobacco when harvesting plants to thank nature. When a bear was killed, a ceremony thanked the bear for "giving" its life.

One study of Ojibwe women who married French fur traders said most of the brides were "exceptional" women. They had "unusual ambitions, influenced by dreams and visions—like the women who become hunters, traders, healers and warriors in Ruth Landes's account of Ojibwe women." From these relationships came the Métis people, whose culture mixed French and Native American elements.

Native American Women as Traders

Native American men were the trappers who killed animals for furs. But usually, women were in charge of the furs their men collected. This made women important in the fur trade. Native American women typically harvested rice and made maple sugar, which were important foods for traders. They were often paid with goods for this work. Accounts of fur traders often mentioned trading goods with women for canoes. One French-Canadian voyageur named Michel Curot listed in his journal that he traded goods for furs with Ojibwe men 19 times, with Ojibwe women 22 times, and another 23 times where he didn't list the gender.

Spiritual Roles of Women

For Native Americans, dreams were seen as messages from the spirit world. This world was much more powerful than their own. Gender roles were not fixed in Native American communities. A woman who dreamed of herself doing a male role could convince her community to let her do that work. This was because it was seen as what the spirits wanted. Ojibwe women in their teenage years went on "vision quests" to find out what the spirits wanted for them.

Native Americans around the Great Lakes believed that when a girl started menstruating, her dreams were special messages from the spirits. Many fur traders noted how women who were thought to have powerful dream-messages played important roles in their communities' decisions. After forming a connection with a spirit at puberty, women would go on more vision quests throughout their lives. They would have more ceremonies and dreams to continue this connection. Netnokwa, a powerful Ojibwe woman in the Red River region, whose dreams were seen as very strong messages, traded directly with fur traders. John Tanner, her adopted son, wrote that she received "ten gallons of spirits" every year from fur traders. It was considered wise to stay on her good side. Whenever she visited Fort Mackinac, "she was saluted by a gun from the fort."

In 1793, Oshahgushkodanaqua, an Ojibwe woman from Lake Superior, married John Johnston, a British fur trader. Later, she told British writer Anna Brownell Jameson how she got married. According to Jameson's 1838 book, Oshahgushkodanaqua said that when she was 13, she went on her "vision quest." She fasted alone in a black lodge on a high hill to find her guardian spirit.

"She dreamed continually of a white man, who approached her with a cup in his hand, saying "Poor thing! Why are you punishing yourself? Why do you fast? Here is food for you!" He was always accompanied by a dog, who looked up at her like he knew her. Also, she dreamed of being on a high hill, which was surrounded by water, and from which she beheld many canoes full of Indians, coming to her and paying her homage; after this, she felt as if she was being carried up into the heavens, and as she looked down on the earth, she perceived it was on fire and said to herself, "All my relations will be burned!", but a voice answered and said, "No, they will not be destroyed, they will be saved!", and she knew it was a spirit, because the voice was not human. She fasted for ten days, during which time her grandmother brought her at intervals some water. When satisfied that she had obtained a guardian spirit in the white stranger who haunted her dreams, she returned to her father's lodge".

About five years later, Oshahgushkodanaqua met Johnston. He asked to marry her, but her father refused. When Johnston returned the next year, her father agreed. But she said no, as she didn't like the idea of being married for life. However, under strong pressure from her father, she eventually married him. Oshahgushkodanaqua accepted her marriage when she decided that Johnston was the white stranger from her dreams. The couple stayed married for 36 years until Johnston's death. Oshahgushkodanaqua played an important role in her husband's business. Jameson also noted that Oshahgushkodanaqua was considered a strong woman among the Ojibwe. She wrote that "in her youth she hunted and was accounted the surest eye and fleetest foot among the women of her tribe."

Northern Athabaskan Peoples

The fur trade seems to have made the status of Native American women weaker in the Canadian sub-arctic. This area includes parts of the Northwest Territories, the Yukon, and northern Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta. The difficult land forced people to live a nomadic life, moving often to find food. The Native Americans in the sub-arctic had only small dogs that couldn't carry heavy loads. Everything had to be carried on the backs of the women.

There was a belief among the Northern Athabaskan peoples that only men could handle weapons. If a woman used a weapon, it would lose its power. Since different groups often fought, men were always armed when traveling, while women carried all the baggage. All the Native American men in the sub-arctic greatly feared menstrual blood. They saw it as unclean and a symbol of threatening femininity.

American anthropologist Richard J. Perry says the key difference between Northern Athabaskan peoples and those further south, like the Cree and Ojibwe, was the presence of waterways for canoes. In the 1700s, Cree and Ojibwe men could travel hundreds of miles by canoe to Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) posts. They sold furs and brought back European goods. Meanwhile, their women largely managed their communities. At York Factory in the 1700s, HBC workers reported that up to 200 canoes would arrive at once, bringing Native American men to trade furs. Usually, Cree and Ojibwe men made the trip to York Factory, while their women stayed in their villages.

Until 1774, the Hudson's Bay Company only operated posts on the shores of Hudson's Bay. Only competition from the North West Company, based in Montreal, forced the Hudson's Bay Company to claim more land. In contrast, the Northern Athabaskan peoples had to travel by foot because there were no waterways flowing into Hudson's Bay (the major river, the Mackenzie, flows into the Arctic Ocean). Women carried the baggage. In this way, the fur trade gave more power to Cree and Ojibwe women, but it made Northern Athabaskan women's lives much harder.

Chipewyan People

The Chipewyan started trading furs for metal tools with the Hudson's Bay Company in 1717. This greatly changed their way of life. They went from hunting for daily survival to being involved in long-distance trade. The Chipewyan became the middlemen between the Hudson's Bay Company and other Native Americans further inland. The Chipewyan were very protective of their right to trade with the Hudson's Bay Company. They stopped groups like the Tłı̨chǫ and Yellowknives from crossing their land to trade directly with the company throughout the 1700s.

For the Chipewyan, who were still living in the Stone Age, metal tools were very valuable. It took hours to heat a stone pot, but only minutes for a metal one. An animal could be skinned much faster with a metal knife than with a stone knife. For many Chipewyan groups, being part of the fur trade meant they lost their ability to support themselves. They killed animals for fur, not food. This made them depend on other groups for food. This led to a cycle where many Chipewyan groups depended on trading furs for European goods, which they then traded for food. This meant they had to make very long trips across the subarctic to Hudson's Bay and back. To make these trips, the Chipewyan traveled through empty land where starvation was a real danger. During these trips, the women had to carry all the supplies. Samuel Hearne of the Hudson's Bay Company, who was sent inland in 1768, wrote about the Chipewyan:

"Their annual haunts, in the quest for furrs [furs], is so remote from European settlement, as to render them the greatest travelers in the known world; and as they have neither horse nor water carriage, every good hunter is under necessity of having several people to assist in carrying his furs to the company's Fort, as well as carrying back the European goods which he received in exchange for them. No persons in this country are so proper for this work as the women, because they are inured to carry and haul heavy loads from their childhood and to do all manner of drudgery".

Hearne's main guide, Matonabbee, told him that women had to carry everything on their long trips because "...when all the men are heavy laden, they can neither hunt nor travel any considerable distance." Perry noted that when Hearne traveled in 1768–1772, the Chipewyan had been trading with the Hudson's Bay Company directly since 1717. They had also traded indirectly through the Cree for at least 90 years. So, the lifestyles Hearne saw had already been changed by the fur trade. But Perry argued that the hard nature of these trips and the burden of carrying everything suggests that Chipewyan women might have had a lower status even before contact with Europeans.

Gwich'in People

When fur traders first met the Gwich'in in 1810, they described a fairly equal society. But the fur trade lowered the status of Gwich'in women. Accounts from the 1860s describe Gwich'in women as almost like slaves, carrying baggage on long journeys. One fur trader wrote that Gwich'in women were "little better than slaves." Another wrote about the "brutal treatment" Gwich'in women suffered from their men. Gwich'in leaders who became rich from the fur trade often had several wives. This caused serious social problems, as young Gwich'in men found it impossible to find a partner because their leaders took all the women.

Importantly, when the Hudson's Bay Company set up trading posts inland in the late 1800s, the status of Gwich'in women improved. Anyone could get European goods by trading at the local HBC post. This ended the ability of Gwich'in leaders to control who got European goods. Also, the introduction of dogs that could pull sleds meant women no longer had to carry everything on their long trips.

Ojibwe People

The Ojibwe believed that if plants and animals were not thanked for "giving" themselves, then they would be less "giving" the next year. The same idea applied to their relationships with other people, like fur traders. The Ojibwe, like other First Nations, believed that animals willingly allowed themselves to be killed. If a hunter didn't thank the animal world, then animals would be less "giving" next time.

The American anthropologist Ruth Landes wrote in her 1937 book Ojibwe Women that Ojibwe society in the 1930s was based on "male supremacy." She thought this was how Ojibwe society had always been. Landes noted that the women she interviewed told her stories about Ojibwe women who, in past centuries, were inspired by their dreams and played important roles as warriors, hunters, healers, traders, and leaders. In 1978, American anthropologist Eleanor Leacock argued that Ojibwe society had actually been equal. But the fur trade changed it. Men could become powerful by getting European goods, which led to Ojibwe women losing their importance.

More recently, American anthropologist Carol Devens argued that contact with French values and the ability to collect "extra goods" from the fur trade changed the equal Ojibwe society into an unequal one where women were less valued. However, some research suggests that the fur trade actually gave more power to Ojibwe women, who played a very important role in the trade. It was the decline of the fur trade that led to the decline of Ojibwe women's status.

Métis People

As fur traders moved west in the early 1800s, they wanted to create the same economic system that had made them money in the northeast. Some went alone, but others relied on companies like the Hudson's Bay Company. Marriage and family ties with Native American women were very important in the western fur trade. White traders who moved west needed to become part of the tribes' family networks. They often did this by marrying a prominent Native American woman. This practice was called a "country" marriage. It allowed the trader to connect with the adult men in the woman's family, who were important allies for trade. The children of these marriages, known as Métis, were a key part of the fur trade system.

The Métis were seen as a unique group with a changing identity. Early in the fur trade, Métis were not defined by their race but by their chosen way of life. These children were usually the offspring of white men and Native American mothers. They were often raised to follow their mother's lifestyle. The father could influence how the child was raised and prevent them from being called Métis in the early years of the western fur trade. Fur trade families often included Native American women who lived near forts and formed networks among themselves. These networks helped create family ties between tribes, which benefited the traders.

Métis were among the first groups of fur traders who came from the northeast. These men were often of mixed heritage, largely Iroquois and other tribes. Many Métis had multiple Native American backgrounds. Lewis and Clark, who opened up the fur trade in the Upper Missouri River, brought many Métis with them as workers. These same Métis became involved in the early western fur trade. Many settled on the Missouri River and married into local tribes before setting up their trade networks. The first generation of Métis born in the West grew up from the old fur trade. They provided a link to the new western empire. These Métis had both Native American and European skills, spoke many languages, and had the important family networks needed for trade. Many also spoke the Michif Métis language. To set themselves apart from Native Americans, many Métis strongly followed Roman Catholic beliefs and avoided Native American ceremonies.

By the 1820s, the fur trade had spread into the Rocky Mountains. American and British interests began to compete for control. The Métis played a key role in this competition. Early Métis gathered around trading posts. They worked as packers, laborers, or boatmen. Through their efforts, they helped create a new system centered on the trading posts. Other Métis traveled with trapping groups in a loose business setup where independence was encouraged. By the 1830s, Canadians and Americans were going west to find new fur supplies. Companies like the NWC and HBC offered jobs for Métis. By the end of the 1800s, many companies considered the Métis to be Native American in their identity. As a result, many Métis left the companies to work independently.

After 1815, the demand for bison robes slowly grew, though beaver was still the main trade item. The 1840s saw a rise in the bison trade as the beaver trade declined. Many Métis adapted to this new economic opportunity. This change made it harder for Métis to work within companies like the HBC. But it made them welcome allies of the Americans, who wanted to push the British to the Canada–U.S. border. Although the Métis initially worked on both sides of the border, by the 1850s they had to choose an identity and settle north or south of the border. The 1850s was a time of movement for the Métis. Many drifted and created new communities or settled within existing Canadian, American, or Native American communities.

A group of Métis who identified with the Chippewa moved to the Pembina in 1819. Then they moved to the Red River area in 1820, near St. François Xavier in Manitoba. In this region, they established several important fur trading communities. These communities were connected through the NWC. This relationship dated back to 1804–1821, when Métis men worked as low-level voyageurs, guides, interpreters, and foremen. From these communities came the Métis buffalo hunters who worked in the robe trade.

The Métis created a whole economic system around the bison trade. Entire Métis families were involved in making robes, which was the main reason for the winter hunt. They also sold pemmican at the posts. Unlike Native Americans, the Métis depended on the fur trade system and were affected by the market. The international prices of bison robes directly influenced the well-being of Métis communities. In contrast, local Native Americans had more diverse resources and were less dependent on Americans and Europeans at this time.

By the 1850s, the fur trade had spread across the Great Plains. The bison robe trade began to decline. The Métis played a role in the decrease of bison. Like Native Americans, the Métis preferred cows, which made it hard for bison herds to grow. Also, floods, droughts, early frosts, and the environmental impact of settlements threatened the herds. Traders, trappers, and hunters all depended on bison to live. The Métis tried to keep their lifestyle in various ways. For example, they often used two-wheel carts made from local materials. This meant they could move more easily than Native Americans and didn't have to follow seasonal hunting patterns.

The 1870s brought an end to bison in the Red River area. Métis communities like those at Red River or Turtle Mountain had to move to Canada and Montana. One resettlement area was the Judith Basin in Montana, which still had some bison in the early 1880s. By the end of the decade, the bison were gone, and Métis hunters moved back to tribal lands. They wanted to be part of treaty negotiations in the 1880s, but their status with tribes like the Chippewa was unclear.

Many former Métis bison hunters tried to get land claims during treaty negotiations in 1879–1880. They were reduced to living on Native American land during this time. They collected bison bones for $15–20 per ton to buy supplies for winter. The reservation system did not ensure that the Métis were protected and accepted as Native Americans. To make things more complicated, Métis had unclear citizenship status. They were often considered unable to give court testimonies and denied the right to vote. The end of the bison robe trade was the end of the fur trade for many Métis. This meant they had to redefine their identity and adapt to a new economic world.

English Colonies and the Fur Trade

By the late 1700s, the four main British fur trading posts were Fort Niagara in modern New York, Fort Detroit and Fort Michilimackinac in modern Michigan, and Grand Portage in modern Minnesota. All were in the Great Lakes region. The American Revolution and new national borders forced the British to move their trading centers north. The new United States also tried to profit from the fur trade, with some early success. But by the 1830s, the fur trade began to decline sharply. Fur was never again as profitable as it had been.

Pacific Coast Fur Trade

On the Pacific coast, the fur trade mainly focused on seals and sea otters. In northern areas, this trade was first started by the Russian-American Company. Later, Spanish/Mexican, British, and U.S. hunters and traders joined in. Non-Russians extended fur hunting areas south to the Baja California Peninsula.

Southeastern United States Fur Trade

Early Days

Starting in the mid-1500s, Europeans traded weapons and household goods for furs with Native Americans in the southeastern United States. The trade first tried to copy the northern fur trade, with many wildcats, bears, beavers, and other fur animals being traded. The trade in fur coat animals decreased in the early 1700s. This was because the trade in deer skins became much more popular. The deer skin trade then became the main focus of relationships between Native Americans in the southeast and European settlers. Deer skin was very valuable because there was a shortage of deer in Europe. The British leather industry needed deer skins to make goods. Most deer skins were sent to Great Britain during the peak of this trade.

After European Contact in the 1500s and 1600s

Spanish explorers in the 1500s had violent encounters with powerful Native American chiefdoms. This led to Native Americans in the southeast becoming less centralized. Almost a century passed between the first Spanish exploration and the next wave of European settlers. This allowed the survivors of European diseases to form new tribes.

Most Spanish trade with Native Americans was limited to the coast until expeditions inland in the early 1600s. By 1639, a significant trade for deer skins developed between the Spanish in Florida and Native Americans. More inland tribes joined this system by 1647. Many tribes across the southeast began sending trading groups to meet the Spanish in Florida. Or they used other tribes as middlemen to get manufactured goods. The Apalachees used the Apalachicola people to collect deer skins. In return, the Apalachees gave them silver, guns, or horses.

As European settlers slowly colonized the southeast, the deerskin trade grew rapidly. This continued into the 1700s. Many white settlers who came to the Carolinas in the late 1600s were from Virginia. There, trading European goods for beaver furs had already started. The white-tailed deer herds south of Virginia were a more profitable resource. The French and English fought for control over southern Appalachia and the Mississippi Valley. They needed alliances with the Native Americans there to stay in power. European settlers used the trade of deer skins for manufactured goods to secure trade relationships and, therefore, power.

The Yamasee War

The Yamasee were a Native American group who lived in what is now South Carolina. In the early 1700s, tensions between the Yamasee and white settlers in colonial South Carolina led to open conflict in 1715. Many of these settlers were fur traders. The conflict almost destroyed the European colonial presence in the American Southeast. It killed 7% of the settler population in South Carolina.

The Yamasee had built up a lot of debt in the early 1700s. They bought manufactured goods on credit from European traders. Many Yamasee could not produce enough deer skins to pay their debts later in the year. Native Americans who could not pay their debts were sometimes forced to work for settlers. This practice also extended to the wives and children of the Yamasees in debt. This made the Yamasees and other tribes angry. They complained about the unfair credit system European traders had set up, but nothing changed. European settlers also encouraged competition between tribes and sold firearms to both the Creek and Cherokee. This competition came from the demand for forced labor in the southeast. Tribes would raid each other and sell captured prisoners of war to European settlers.

Starting on April 14, 1715, the Yamasee launched many attacks against white settlements in South Carolina. They killed traders and pushed settlers back from the frontier to Charles Town. In the conflict, the Yamasee got help from the Catawba, Creek, Cherokee, Waxhaw, and Santee. They formed a large alliance. However, the South Carolinian settlers eventually defeated the Yamasee. This happened because the Catawba and Cherokee switched sides, strengthening their existing trade partnerships.

The French had tried to stop raids for forced labor in regions they controlled. This was because their Native American allies, the Choctaws, Chickasaws, and Yazoos, suffered most from such raids. Firearms were essential trade items for Native Americans to protect themselves from these raids. This need drove the intensity of the deerskin trade. The demand for Native American forced labor decreased as enslaved Africans began to be imported in larger numbers. The trade's focus returned to deerskins. Another reason for the decline in demand for Native American forced labor was the Yamasee War. White settlers became convinced they needed to avoid similar conflicts.

After the conflict ended, the Native American peoples in the region returned to making alliances with European powers. They used smart political moves to get the best deals by playing the nations against each other. The Creeks were especially good at this. They had started trading with South Carolina in the late 1600s and became a trusted deerskin supplier. The Creeks were already a successful tribe because they controlled the most valuable hunting lands, especially compared to the poorer Cherokees. Because they allied with the British during the Yamasee War, the Cherokees lacked Native American trading partners. They couldn't afford to break with Britain to negotiate with France or Spain.

Mississippi River Valley

From their bases in the Great Lakes area, the French steadily moved down the Mississippi River valley to the Gulf of Mexico starting in 1682. At first, French relations with the Natchez Native Americans were friendly. In 1716, the French built Fort Rosalie (modern Natchez, Mississippi) within Natchez territory. In 1729, after several cases of French land fraud, the Natchez burned down Fort Rosalie and killed about 200 French settlers. In response, the French and their allies, the Choctaw, fought a very destructive campaign against the Natchez. After the French victory over the Natchez in 1731, which led to the destruction of the Natchez people, the French could begin fur trading down the Arkansas River. They greatly expanded the Arkansas Post to take advantage of the fur trade.

Mid-1700s Trade

Deer skin trade was most profitable in the mid-1700s. The Creeks became the largest deer skin supplier. The increase in supply only made European demand for deer skins stronger. Native Americans continued to negotiate the best trade deals. They forced Britain, France, and Spain to compete for their supply of deer skins. In the 1750s and 1760s, the Seven Years' War made it hard for France to provide manufactured goods to its allies, the Choctaws and Chickasaw. The French and Indian War further disrupted trade, as the British blocked French goods. The Cherokees allied with France, who were forced out of the southeast by the Treaty of Paris in 1763. The British became the main trading power in the southeast.

Both the Cherokee and the Creek were main trading partners of the British, but their relationships were different. The Creeks adapted to the new economic trade system and kept their old social structures. Originally, Cherokee land was divided into five areas. But the number soon grew to thirteen areas, with 200 hunters assigned per area, because of the high demand for deer skins.

Charleston and Savannah were the main ports for exporting deer skins. Deer skins became the most popular export. They financially supported the colonies with the money from taxes on them. Charleston's trade was regulated by the Indian Trade Commission. This group of traders controlled the market and made money from selling deer skins. From the early 1700s to mid-century, Charleston's deer skin exports more than doubled. Charleston received tobacco and sugar from the West Indies and rum from the north in exchange for deer skins. In return, Great Britain sent woolens, guns, ammunition, iron tools, clothing, and other manufactured goods to trade with Native Americans.

After the Revolutionary War

The Revolutionary War disrupted the deer skin trade. The import of British manufactured goods was cut off. The deer skin trade had already started to decline because deer were over-hunted. The lack of trade meant Native Americans ran out of items, like guns, that they depended on. Some Native Americans, like the Creeks, tried to restart trade with the Spanish in Florida, where some loyalists were also hiding. When the war ended with the British leaving, many tribes who had fought on their side were left unprotected. They had to make peace and new trading deals with the new country. Many Native Americans faced violence from the new Americans who wanted to settle their land. The new American government made treaties that recognized pre-war borders, such as with the Choctaw and Chickasaw, and allowed open trade.

In the two decades after the Revolutionary War, the United States government made new treaties with Native Americans. These treaties set up hunting grounds and trade terms. But the value of deer skins dropped as domesticated cattle took over the market. Many tribes soon found themselves in debt. The Creeks began to sell their land to the government to try and pay their debts. Fighting among Native Americans made it easy for white settlers to move onto their lands. The government also tried to encourage Native Americans to give up their old ways of hunting for survival. They wanted them to turn to farming and raising cattle for trade.

Cultural Impact of the Fur Trade

The fur trade and the people involved have appeared in films and popular culture. It was the subject of books and movies, from James Fenimore Cooper to Irving Pichel's Hudson's Bay (1941), the Canadian musical My Fur Lady (1957), and Nicolas Vanier's documentaries.

Chantal Nadeau, a communications scientist, talks about the "country wives" and "country marriages" between Native American women and European fur trappers. She also mentions the Filles du Roy of the 1700s. Nadeau says that women were sometimes described as a type of commodity, "skin for skin," and they were essential for the fur trade to continue. Nadeau describes fur as a key part of Canadian identity. She notes the debates around the Canadian seal hunt, with Brigitte Bardot as a leading figure. Bardot's involvement in anti-fur campaigns was at the request of author Marguerite Yourcenar. Yourcenar asked Bardot to use her fame to help the anti-sealing movement. Bardot succeeded as an anti-fur activist, becoming known as the "mama of white seal babies."

The Fur Trade Today

Modern fur trapping and trading in North America is part of a larger $15 billion global fur industry. Wild animal pelts make up only 15% of all fur produced. In 2008, the global recession hit the fur industry and trappers especially hard. Fur prices dropped greatly because fewer expensive fur coats and hats were sold. This drop in fur prices is similar to trends seen in past economic downturns.

In 2013, the North American Fur Industry Communications (NAFIC) group was created. It's a program to educate the public about the fur industry in Canada and the U.S. NAFIC shares information online under the name "Truth About Fur."

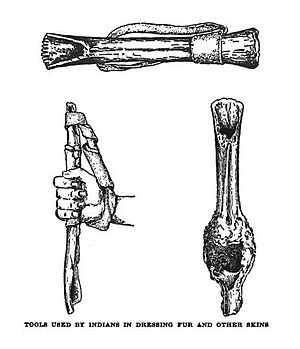

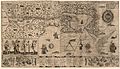

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Comercio de pieles norteamericano para niños

In Spanish: Comercio de pieles norteamericano para niños