Samuel Hearne facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Samuel Hearne

|

|

|---|---|

Samuel Hearne

|

|

| Born | February 1745 |

| Died | November 1792 (aged 47) London, England

|

| Occupation | Explorer, Author, Governor |

| Known for | Exploring |

Samuel Hearne (born February 1745 – died November 1792) was an English explorer, fur trader, writer, and naturalist. He was the first European to travel across northern Canada to the Arctic Ocean. He reached the Arctic Ocean by following the Coppermine River to Coronation Gulf. In 1774, Hearne built Cumberland House for the Hudson's Bay Company. This was their first trading post far from the coast and the first lasting settlement in what is now Saskatchewan.

Contents

Samuel Hearne was born in London, England, in February 1745. His father worked for the London Bridge Waterworks but passed away in 1748. Samuel had a younger sister named Sarah.

When he was just 11 years old, in 1756, Samuel Hearne joined the British Royal Navy. He became a midshipman under Captain Samuel Hood. Hearne stayed with Captain Hood during the Seven Years' War. He saw a lot of fighting, including the bombing of Le Havre. After serving in the English Channel and the Mediterranean Sea, he left the Navy in 1763.

Joining the Hudson's Bay Company

In February 1766, Hearne started working for the Hudson's Bay Company. He was a mate on a ship called the Churchill. This ship was involved in trading with the Inuit people from Prince of Wales Fort in Churchill, Manitoba. Two years later, he became a mate on another ship, the Charlotte. He also took part in the company's short-lived whale hunting business.

In 1767, Hearne found what was left of James Knight's expedition. In 1768, he explored parts of the Hudson Bay coast. He was looking for ways to improve cod fishing. During this time, he became known for his skill in snowshoeing.

Hearne also got better at navigation by watching William Wales. Wales was an astronomer who came to Hudson Bay in 1768–1769. He was there to observe the Transit of Venus for the Royal Society.

Hearne's Amazing Explorations

The English people at Hudson Bay knew that the First Nations people to the northwest used native copper. This is why places like Yellowknife got their name. In 1768, a northern First Nation group brought pieces of copper to Churchill. The governor, Moses Norton, decided to send Hearne to find a possible copper mine.

Hearne's journeys showed how little the Europeans knew about traveling in this difficult land. They relied heavily on the First Nations people, who understood the land and how to find food.

First Journey: A Tough Start

Hearne's first journey began on November 6, 1769. The plan was to walk over the frozen ground because there were no canoe routes. They had to carry as much food as possible and then find food along the way. Hearne hoped to join a group of northern First Nations people who had come to trade. He wanted them to lead him to the copper mine.

He left Churchill with two company workers and two Cree hunters. A group of Chipewyan people also joined them. They went north across the Seal River. By November 19, their European food ran out. The hunters found very little game. Hearne had started too late in the year, and the caribou had already left the open Barren Grounds for the forests.

They headed west and north, finding only a few ptarmigan birds, fish, and three stray caribou. The Indigenous people, who knew the land, were smarter than to risk starving. They began to leave the group. When the last First Nations people left, Hearne and his European friends went back to the Seal River valley. There, they found some venison and reached Churchill on December 11.

Second Journey: Learning from Mistakes

Since he couldn't control the northern First Nations, Hearne decided to try again. This time, he used "home guards," who were Cree people living around the trading post. They hunted in exchange for European supplies. He left Churchill on February 23.

He reached the Seal River and found good hunting. He followed the river west until he reached a large lake, probably Sethnanei Lake. He decided to wait there for better weather and live by fishing. In April, the fish started to become scarce. On April 24, many Indigenous people, mostly women, arrived from the south for the yearly goose hunt. On May 19, the geese arrived, and there was plenty of food.

They headed north and east past Baralzone Lake. By June, the geese had flown further north, and they faced hunger again. At one point, they killed three muskoxen and had to eat them raw because it was too wet to make a fire. They crossed the Kazan River above Yathkyed Lake, where they found good hunting and fishing. Then they went west to Lake Dubawnt, which is about 450 miles (724 km) northwest of Churchill.

On August 14, Hearne's quadrant (a tool for navigation) broke. This explains why his maps for the rest of this journey and the next one were not very accurate. Hearne returned to Churchill in the autumn. On his way back, he met Matonabbee, who would be his guide for the next journey. Matonabbee likely saved him from freezing or starving. Much of the land Hearne crossed on his second journey was very empty. It was not properly explored again until Joseph Tyrrell in 1893.

Third Journey: Reaching the Arctic Ocean

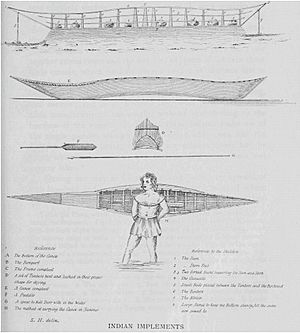

For his third journey, Hearne traveled as the only European with a group of Chipewyan guides. Their leader was Matonabbee. The group also included eight of Matonabbee's wives. They helped carry supplies, set up camp, and cook. This expedition started in December 1770. Their goal was to reach the Coppermine River in summer. From there, they could use canoes to go down to the Arctic Ocean.

Matonabbee kept a fast pace. They reached the great caribou crossing before their food ran out. They arrived just in time for the spring hunt. Here, Northern First Nations (Dene) hunters gathered to hunt the huge herds of caribou moving north for the summer. They stored a lot of meat for Hearne's trip. A group of "Yellowknife" Dene joined the expedition. Matonabbee told his wives to wait for his return in the Athabasca country to the west.

The Dene people were generally peaceful. However, they were in conflict with the Inuit. Many Yellowknife First Nations joined Hearne's group. They wanted to go to the Coppermine River to kill Inuit, who were known to be in that area.

On July 14, 1771, they reached the Coppermine River. It was a small stream flowing over rocks in the "Barren Lands of the Little Sticks." A few miles down the river, just above a waterfall, they found the dome-shaped wigwams of an Eskimo camp. At 1 AM on July 17, 1771, Matonabbee and the other Indigenous peoples attacked the sleeping "Esquimaux." About twenty people were killed in what became known as the Massacre at Bloody Falls.

A few days later, Hearne became the first European to reach the shore of the Arctic Ocean by land. By following the Coppermine River to the Arctic Ocean, he proved that there was no Northwest Passage through the continent at lower latitudes.

This expedition also succeeded in its main goal: finding copper in the Coppermine River area. However, a thorough search only found one four-pound piece of copper. Mining it for money was not seen as possible.

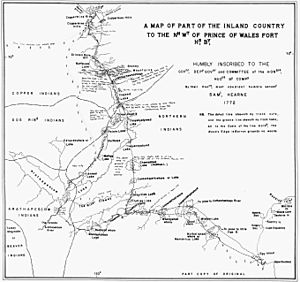

Matonabbee led Hearne back to Churchill by taking a wide path to the west. They passed Bear Lake in Athabasca Country. In the middle of winter, Hearne became the first European to see and cross Great Slave Lake. Hearne returned to Fort Prince of Wales on June 30, 1772. He had walked about 5,000 miles (8,047 km) and explored more than 250,000 square miles (647,497 km²) of land.

Later Life and Legacy

In 1774, Hearne was sent to Saskatchewan to build Cumberland House. This was the second trading post built by the Hudson's Bay Company away from the coast. (The first was Henley House, built in 1743). Hearne had learned to live off the land. He took very few supplies for the eight Europeans and two Home Guard Crees who went with him.

After talking to some local chiefs, Hearne chose a good spot on Pine Island Lake in the Saskatchewan River. This spot was linked to both the Saskatchewan River trade route and the Churchill system.

Hearne became the governor of Fort Prince of Wales on January 22, 1776. On August 8, 1782, Hearne and his 38 civilians faced a French force. This force was led by the comte de La Pérouse. They had three ships, including one with 74 guns, and 290 soldiers. As a former Navy man, Hearne knew the odds were hopeless. He surrendered without a fight. Hearne and some other prisoners were allowed to sail back to England from Hudson Strait in a small ship.

Hearne returned the next year, but trade had gotten worse. The First Nations population had been greatly reduced by European diseases like measles and smallpox. They also suffered from hunger because they lacked normal hunting supplies like gunpowder and shot. Matonabbee had died, and the other main First Nations leaders from Churchill had moved to other posts. Hearne's health began to fail. He gave up command at Churchill on August 16, 1787, and returned to England.

In the last ten years of his life, Hearne used his experiences to help naturalists like Thomas Pennant. His friend William Wales, who was a teacher, helped Hearne write his book. The book was called A Journey from Prince of Wales's Fort in Hudson's Bay to the Northern Ocean. It was published in 1795, three years after Hearne died from dropsy in November 1792 at age 47.

Hearne's Lasting Impact

On July 1, 1767, Samuel Hearne carved his name into a smooth stone at Sloop's Cove. This place is near Fort Prince of Wales, and his name can still be seen there today.

One of William Wales's students was the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Coleridge briefly mentioned Hearne's book in his notebook. Hearne's adventures might have helped inspire Coleridge's famous poem, Rime of the Ancient Mariner.

Charles Darwin also mentioned Hearne in his book, The Origin of Species. Darwin wrote:

In North America the black bear was seen by Hearne swimming for hours with widely open mouth, thus catching, like a whale, insects in the water.

Samuel Hearne's story of his northern explorations, A Journey from Prince of Wales' Fort in Hudson's Bay to the Northern Ocean, was first published in 1795. It was later edited by Joseph Tyrell and reprinted.

There is a Junior/Senior High School named after him in Inuvik, Northwest Territories. A school in Toronto, Ontario, was also built and named after him in 1973.

See also

In Spanish: Samuel Hearne para niños

In Spanish: Samuel Hearne para niños

| William Lucy |

| Charles Hayes |

| Cleveland Robinson |