Thomas Pennant facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Thomas Pennant

|

|

|---|---|

Thomas Pennant by Thomas Gainsborough (1776)

|

|

| Born | 27 June [O.S. 14 June] 1726 Downing Hall, Whitford, Flintshire, Wales

|

| Died | 16 December 1798 (aged 72) Downing Hall, Whitford, Flintshire, Wales

|

| Occupation | |

| Known for | Writings on natural history, geology and geographical expeditions |

Thomas Pennant (27 June [O.S. 14 June] 1726 – 16 December 1798) was a Welsh naturalist, explorer, writer, and antiquarian. He was born and lived his whole life at his family home, Downing Hall near Whitford, Flintshire, in Wales.

Thomas Pennant was very curious about nature. He studied the land, rocks, plants, and animals around him. He wrote famous books like British Zoology and History of Quadrupeds. Even though he wrote about animals from all over the world, he only traveled in Europe. He knew many scientists of his time and wrote letters to them. His books even influenced other famous writers like Samuel Johnson. Pennant also collected many interesting art pieces and other items, mostly because they were scientifically important. Many of these are now kept at the National Library of Wales.

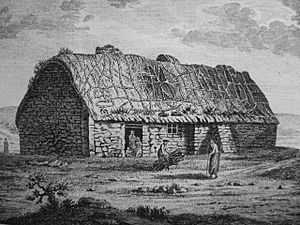

As an explorer, he visited Scotland and many other parts of Britain. He wrote popular travel books about these trips. Many places he visited were not well-known to people in Britain. His travel books, with their colorful pictures, were very popular. Each trip started from his home. He wrote about the route, the scenery, and the daily lives of people he met. He also described their customs, old stories, and the wildlife he saw. He traveled on horseback with his servant, Moses Griffith. Moses would sketch what they saw, and later turn these into illustrations for the books. Thomas Pennant was a friendly man with many friends. He stayed busy with his interests even into his sixties. He lived a healthy life and died at Downing when he was 72.

Contents

Early Life and Family Home

The Pennant family were Welsh gentry from Whitford, Flintshire. They had a small estate called Bychton. In 1724, Thomas's father, David Pennant, inherited the nearby Downing estate. This made the family much wealthier. Downing Hall, where Thomas was born, became their main home.

The house was built in 1600. By the time the Pennants moved in, it needed many repairs. They made many changes to it. The house had beautiful rooms, including a large library. It also had a smoking room filled with old carvings and animal horns. The gardens were also very wild. The family worked hard to improve them, adding paths and pleasant areas.

Education and Interests

Pennant first went to Wrexham Grammar School. In 1740, he moved to Thomas Croft's school in Fulham. When he was 12, Pennant said he became very interested in natural history. This happened after he received a book called Ornithology by Francis Willughby. In 1744, he went to Queen's College, Oxford, and later to Oriel College.

Like many wealthy students, he left Oxford without a degree. However, in 1771, he received an honorary degree. This was to recognize his important work as a zoologist.

Pennant married Elizabeth Falconer in 1759. They had a son, David Pennant, born in 1763. Sadly, Pennant's wife died the next year. Fourteen years later, he married Ann Mostyn.

In 1746–47, Pennant visited Cornwall. There he met William Borlase, who was also interested in old things and nature. This visit sparked Pennant's interest in minerals and fossils. These became his main scientific focus in the 1750s. In 1750, he wrote about an earthquake at Downing. This article was published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. In 1756, another paper appeared about coral-like items he found.

Pennant used his knowledge of geology in a practical way. He opened a lead mine. The money from this mine helped him pay for improvements at Downing. He inherited the estate in 1763.

In 1754, he became a member of the Society of Antiquaries. But by 1760, he resigned. He said his finances were tight, and he wanted to stay at home. When his money situation improved, he became a supporter of the arts and a collector. He gathered many artworks. He chose them for their scientific interest, not just their beauty.

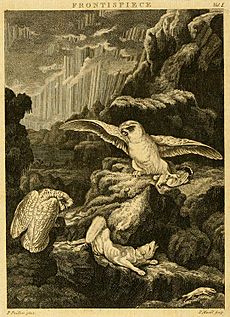

His collection included works by Nicholas Pocock showing landscapes in Wales. He also had paintings by Peter Paillou showing different climate types. His portrait by Thomas Gainsborough shows him as a country gentleman. The "Pennant Collection" at the National Library of Wales also has many watercolors by Moses Griffith and John Ingleby. Pennant himself made some drawings too.

The artist Moses Griffith worked full-time for Pennant. He lived at Downing and drew pictures for most of Pennant's books. Many of these paintings are now at the National Museum of Wales. Pennant also sometimes hired John Ingleby. Ingleby mostly drew town scenes and small pictures called vignettes.

Pennant was a landowner who liked to improve his property. He also supported the government and church. In 1761, he served as high sheriff of Flintshire. He was against popular calls for changes to Parliament.

Scientific Work and Books

Early Writings

Pennant's first published works were scientific papers. They were about the earthquake he felt, other geology topics, and palaeontology (the study of fossils). One of these papers impressed Carl Linnaeus so much that in 1757, Linnaeus suggested Pennant become a member of the Royal Swedish Society of Sciences. Pennant was very honored and continued to write letters to Linnaeus.

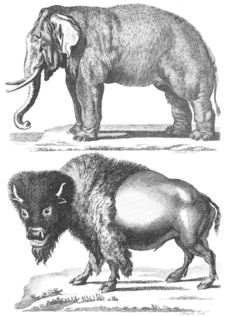

Pennant noticed that naturalists in other European countries were writing books about their local animals. So, in 1761, he started a similar book about Britain. It was called British Zoology. This was a large book with 132 color pictures. It was published in 1766 and 1767 in four volumes. More editions followed. The pictures were very expensive to make, so he earned little money. Any profit he made, he gave to charity. For example, he gave money from one edition to the Welsh Charity School. Later, more parts were added. The text, mostly from his own observations, was translated into Latin and German. Pennant's observations in British Zoology were so good that they could be used to study animal populations today.

The book took several years to write. During this time, Pennant's wife died. Soon after, in February 1765, he traveled to Europe. He started in France. There he met other naturalists and scientists. These included the Comte de Buffon, Voltaire, Haller, and Pallas. They continued to write letters to each other. Pennant later felt that the Comte de Buffon used some of his animal observations without giving him credit. His meeting with Pallas was important. It led Pennant to write his Synopsis of Quadrupeds. Pennant and Pallas got along very well. Both admired the English naturalist John Ray. Pallas was supposed to write the book, but he was called away by Empress Catherine the Great to Russia. She asked him to lead a long expedition. So, Pennant took over the project.

In 1767, Pennant became a member of the Royal Society. Around this time, he met the well-traveled Sir Joseph Banks. Banks gave him the skin of a new type of penguin from the Falkland Islands. Pennant wrote about this bird, the king penguin (Aptenodytes patagonicus), and all other known penguin species. This was published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society.

Journeys in Scotland

While working on the Synopsis of Quadrupeds, Pennant decided to travel to Scotland. It was a less explored country and no naturalist had visited it before. He started in June 1769. He kept a diary and made sketches as he traveled. On his way, he visited the Farne Islands and was amazed by the many seabirds nesting there. He entered Scotland near Berwick-on-Tweed. He then traveled up the east coast, through Edinburgh, Perth, Aberdeen, and Inverness. His return journey took him through Fort William, Glen Awe, Inverary, and Glasgow. He didn't like the climate much, but he was interested in everything he saw. He asked about the local economy. He described the scenery around Loch Ness in detail. He loved the Arctic char, a fish new to him. He saw red deer, black grouse, white hares, and ptarmigan. He also saw the capercaillie in the forests. He asked about fishing and trade in the places he visited. He also went to large houses and reported on the old items he found. He finished his trip by visiting Edinburgh again. Then he traveled through Moffat, Gretna, and Carlisle back to Wales. The trip took about three months. When he returned home, Pennant wrote about his tour in Scotland. It was very popular and may have made more English people want to visit Scotland.

In 1771, his Synopsis of Quadrupeds was published. A second edition was made larger and called A History of Quadrupeds. At the end of 1771, he published A Tour in Scotland, 1769. This book was so popular that he decided to take another trip. In the summer of 1772, he left Chester with two friends. They were the Rev. John Lightfoot, a naturalist, and Rev. J. Stewart, who knew a lot about Scottish customs. They traveled through the Lake District, Carlisle, Eskdale, Dumfries, and Glasgow. Pennant was fascinated by a story about the Solway Moss peatbog bursting and flooding the land.

The group then sailed in a boat from Greenock to explore the outer islands. They first visited Bute and Arran, then went to Ailsa Craig. Pennant was interested in the birds, frogs, and shellfish. He studied where they lived. The boat then sailed around the Mull of Kintyre to Gigha. They wanted to go to Islay but the wind stopped. During this wait, Pennant started writing about the ancient history of the Hebrides. When the wind returned, they went to Jura.

Here, like everywhere else, they were welcomed warmly. They were lent horses to explore the island and shown the main sights. Pennant wrote about the scenery, customs, and old stories of the people. They later reached Islay. There, Pennant found geese nesting on the moors. This was a more southerly nesting place for geese than had been known before. Their journey then took them to Colonsay, Iona, Canna, and finally to Mull and Skye. Bad weather stopped them from going to Staffa.

Returning to the mainland, the group left their boat. They tried to travel north to the very tip of Scotland. But they faced bogs, dangerous rocks, and land that was too difficult to cross. They had to turn back. They returned to Skye for a while. Then they split up. Pennant continued his tour, while his friends went back to England. Lightfoot took with him most of the notes he would use for his book, Flora Scotica. Pennant visited Inverary, Dunkeld, Perth, and Montrose. In Montrose, he was surprised to learn that many thousands of lobsters were caught and sent to London each year. He then traveled through Edinburgh, Roxburghshire, and along the River Tweed. He crossed the border at Birgham. Once in England, he quickly traveled home to Downing.

Later Writings

Pennant's next book, in 1774, was about his second journey to Scotland. It had two volumes, with the second appearing in 1776. These books contain so much detail about the countryside, its economy, nature, and people's customs. They are still interesting today to compare with how things are now. While preparing these books, he started new projects. In 1773, he returned to Cumberland, Westmorland, and Yorkshire. He visited parts he had missed before. Like all his tours, he traveled on horseback, keeping a daily diary. Moses Griffith went with him, making many sketches. Pennant seemed to be a simple, friendly man. He was welcomed into strangers' homes wherever he went. He also toured Northamptonshire and the Isle of Man. Whenever he traveled to London, he took a slightly different route. He recorded what he saw and did. Years later, he used these notes to write his Journey from Chester to London. On one of these trips, a church he visited in Buckingham collapsed that evening.

Over the next few years, Pennant made several trips in North Wales. Like his other tours, he started from Downing. Almost 100 pages in the first book he wrote were about the old city of Chester. In these books, he focused on history and old buildings, rather than nature. He was interested in Owain Glyndŵr and his fight with Henry IV for power in Wales. The first volume of Tour in Wales was published in 1778. But it covered only a small part of the country. To fix this, he wrote Journey to Snowdon (part one in 1781 and part two in 1783). These later became the second volume of his Tour. These books also focused on history. But they gave some information on animals and plants, with help from Reverend Lightfoot. Pennant included stories about the strongwoman and harpist Marged ferch Ifan, though he never met her. Pennant also wrote about beavers living on the River Conwy. A deep part of the river was known as "Llyn yr afangc" (Beaver's pool). He also recorded herons nesting at the top of the cliffs at St Orme's Head. Below them, noisy gulls, razorbills, guillemots, and cormorants had their own nesting areas.

Pennant's interests were very broad. In 1781, he published a paper in the Philosophical Transactions about where the turkey came from. He argued it was a North American bird, not an Old World species. Another paper, suggested by Sir Joseph Banks, was about earthquakes. He had felt several in Flintshire. In the same year, he became an honorary member of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. In 1783, he was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. He also became a member of the Swedish Royal Physiographic Society in Lund. In 1791, he was elected a member of the American Philosophical Society.

In 1782, Pennant published his Journey from Chester to London. He had planned to write a "Zoology of North America." But he felt sad about Britain losing control of America. So, he changed it to Arctic Zoology. The book was published with pictures by Peter Brown in 1785–1787. The first volume was about quadrupeds (four-legged animals) and the second about birds. Sir Joseph Banks's trip to Newfoundland in 1786 helped with the bird volume. The book was translated into German and French, and part of it into Swedish. The books were highly praised. Pennant became a member of the American Philosophical Society. In 1787, an extra volume was published. It had more information on North American reptiles and fish.

Pennant is not often thought of as a poet. But in 1782, he wrote a "beautiful little poem" called Ode to Indifference. He explained he wrote it because a lady praised "Indifference."

In 1790, he published his Account of London. This book had many editions. It was written like his other works. It contained historical facts about the parts of London he explored. By this time, he preferred to travel in his imagination. He published a second edition of his Indian Zoology. He also had an idea to write a book about the whole world. He started on the first two volumes of what was planned to be a 14-volume series. Each country would have maps, sketches, color pictures, and information about its products and nature. All this information came from other writers who had visited these places. The first two volumes came out in early 1798. They covered most of India and Ceylon. Volumes three and four included parts of India east of the Ganges, Malaysia, Japan, and China. But before these were published, his health slowly declined. He died at Downing in December 1798. His son, David, edited and published these two volumes after his death. He also published other short papers and Pennant's own story of his life, The literary life of the late Thomas Pennant, Esq. By himself.

Friends and Letters

Pennant met and wrote many letters to other naturalists for years. This gave him special access to their notes and specimens. His writings sometimes tell us about discoveries that would otherwise be lost. For example, he visited the botanist Joseph Banks in September 1771. Banks had just returned from Captain James Cook's four-year exploration trip. Banks seems to have given his bird specimens to Pennant. Pennant's notes describe the birds Banks saw on the trip. When he read John Latham's A General Synopsis of Birds (1781–1785), Pennant saw that Latham had missed some land birds Banks collected from Eastern Australia. He wrote to Latham to fill in the missing information. The naturalist Peter Simon Pallas asked Banks to tell Pennant about "the unhappy fate of CaptTemplate:N. – Cook." In December 1779, Pallas wrote to Pennant himself, telling the story.

Letters from the parson-naturalist Gilbert White to Pennant form the first part of White's 1789 book, The Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne. It is likely that Gilbert's brother, Benjamin White (Pennant's publisher), introduced them. Gilbert was eager to write letters. It was a way to share ideas since there were no scientific groups in Selborne. He knew that Pennant, who wasn't great at fieldwork, was collecting observations for his books. White quickly decided he would use the letters for his own purposes. He kept copies of every letter he sent to Pennant. White was more careful than Pennant and sometimes pointed out mistakes. For example, in 1769, he said that the goatsucker did not only make its sound while flying, as Pennant claimed. So, it was wrong to think the noise came from air hitting its "vastly extended mouth." Pennant accepted White's comments kindly. Unfortunately, Pennant's letters to White have been lost. White's Natural History starts with 44 of White's letters to Pennant. The first nine were never mailed. The other 35 letters are from August 4, 1767, to November 30, 1780. They covered topics like whether swallows sleep through winter or fly away (letter 10), ring ousels (letter 20), whether peacock trains are really tails (letter 35), and thunderstorms (letter 44).

Books by Thomas Pennant

- The British Zoology, Class 1, Quadrupeds. 2, Birds. J. and J. March, 1766.

- A Tour in Scotland 1769. John Monk, 1771.

- A Synopsis of Quadrupeds. John Monk, 1771.

- A Tour in Scotland, and Voyage to the Hebrides 1772. John Monk, 1774.

- Genera of Birds. Balfour and Smellie, 1773.

- British Zoology. Benjamin White, 1776–1777.

- A Tour in Wales. H.D. Symonds, 1778 & 1781.

- A History of Quadrupeds. John Monk, 1781.

- Free Thoughts on the Militia Laws. Benjamin White, 1781.

- The Journey to Snowdon. Henry Hughs, 1781.

- The Journey from Chester to London. Benjamin White, 1782.

- Arctic Zoology. Henry Hughs, 1784–1787.

- Of the Patagonians. George Allan (private press), 1788.

- Of London. Robert Faulder, 1790.

- Indian Zoology. Robert Faulder, 1790.

- A Letter to a Member of Parliament: On Mail-Coaches. R. Faulder, 1792.

- The Literary Life of the Late Thomas Pennant. Benjamin and J. White, 1793.

- The History of the Parishes of Whiteford and Holywell. Benjamin and J. White, 1796.

- The View of Hindoostan. Henry Hughs, 1798–1800.

- Western Hindoostan. Henry Hughs, 1798.

- The View of India extra Gangem, China, and Japan. L. Hansard, 1800.

- The View of the Malayan Isles, New Holland, and the Spicy Isles. John White, 1800.

- A Journey from London to the Isle of Wight. E. Harding, 1801.

- From Dover to the Isle of Wight. Wilson, 1801.

- A Tour from Downing to Alston-Moor. E. Harding, 1801.

- A Tour from Alston-Moor to Harrowgate, and Brimham Crags. J. Scott, 1804.

Pennant's Legacy

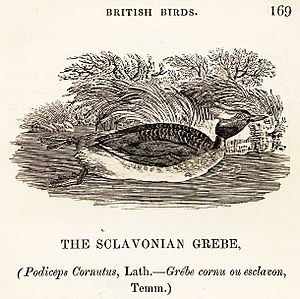

After Pennant died, the French zoologist Georges Cuvier wrote that a scientist's life is best understood by looking at their work. Thomas Bewick often quoted Pennant in his famous bird guide, A History of British Birds (1797 and 1804). For example, Bewick wrote that "Pennant says there are instances, though rare, of their having bred in Snowdon Hills" about the Golden Eagle. Bewick also quoted Pennant for facts about rare birds like "The Sclavonian Grebe." Pennant's knowledge was sometimes very specific. For the Great-Crested Grebe, Bewick noted that its nest "is made of various kinds of dried fibres, stalks and leaves of water plants, and (Pennant says) of the roots of bugbane, stalks of water-lily, pond-weed and water-violet."

The naturalist Richard Mabey called Pennant "a brave and open-minded traveler." He said Pennant's Tours were very popular in their time. Mabey also mentioned Samuel Johnson's comment that Pennant was "the best traveler I ever read." However, Mabey also felt that Pennant was not great at fieldwork. He thought Pennant was more of an "intellectual entrepreneur." This means he was good at sharing and organizing other people's observations and ideas. This helped him create many easy-to-read guides. Mabey added that Pennant sometimes used information from others without enough credit. But he admitted that Pennant was an innovative author. He sought original reports from a wide network of observers. This met the public's interest in natural history writing in the 1760s.

Pennant's exploration of the Western Isles of Scotland was shown in a TV show. Nicholas Crane revisited his journey in a BBC Two documentary in 2007. It was part of the "Great British Journeys" series. Pennant was the focus of the first episode.

The Cymdeithas Thomas Pennant (Thomas Pennant Society) was started in 1989. Its goal is to keep Pennant's memory alive. The society organizes events related to him. This includes publishing leaflets, holding talks, and arranging walks in "Pennant Country." In 2013, the society suggested that "Holywell and the north Flintshire area" be called 'Pennant Country'. Some local council members had questions about this idea.

Species Named After Thomas Pennant

Many marine species have been named after Thomas Pennant. Their scientific names include pennanti, pennantii, and pennantiana. Here are some examples:

- Anchomasa pennantiana Leach in Gray, 1852: now called Barnea parva (Pennant, 1777)

- Arca pennantiana Leach in Gray, 1852: now called Striarca lactea (Linnaeus, 1758)

- Argentina pennanti Walbaum, 1792: now called Maurolicus muelleri (Gmelin, 1789)

- Blennius pennantii Yarrell, 1835: now called Chirolophis ascanii (Walbaum, 1792)

- Cardium pennanti Reeve, 1844: now called Laevicardium crassum (Gmelin, 1791)

- Cardium pennantii Reeve, 1844: now called Laevicardium crassum (Gmelin, 1791)

- Coregonus pennantii

- Ebalia pennantii Leach, 1817: now called Ebalia tuberosa (Pennant, 1777)

- Funambulus pennantii

- Gibbula pennanti (Philippi, 1846)

- Lamna pennanti (Walbaum, 1792): now called Lamna nasus (Bonnaterre, 1788)

- Maurolicus pennanti (Walbaum, 1792): now called Maurolicus muelleri (Gmelin, 1789)

- Ovula pennantiana Leach, 1847: now called Simnia patula (Pennant, 1777)

- Pasiphaë pennantia Leach in Gray, 1852: now called Timoclea ovata (Pennant, 1777)

- Pekania pennanti (1771) common name: fisher

- Procolobus pennantii Waterhouse, 1838

- Selachus pennantii Cornish, 1885: now called Cetorhinus maximus (Gunnerus, 1765)

- Squalus pennanti Walbaum, 1792: now called Lamna nasus (Bonnaterre, 1788)

- Tetrodon pennantii Yarrell, 1836: now called Lagocephalus lagocephalus lagocephalus (Linnaeus, 1758)

- Trochus pennanti Philippi, 1846: now called Gibbula pennanti (Philippi, 1846)

- Venus pennanti Forbes, 1838: now called Chamelea striatula (da Costa, 1778)

- Venus pennantii Forbes, 1838: now called Chamelea striatula (da Costa, 1778)

- Vermilia pennantii Quatrefages, 1866: now called Pomatoceros triqueter (Linnaeus, 1758): now called Spirobranchus triqueter (Linnaeus, 1758)

| Stephanie Wilson |

| Charles Bolden |

| Ronald McNair |

| Frederick D. Gregory |