Thomas Bewick facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Thomas Bewick

|

|

|---|---|

Portrait by James Ramsay

|

|

| Born | c. 11 August 1753 Mickley, Northumberland, England

|

| Died | 8 November 1828 (aged 75) |

| Occupation |

|

| Spouse(s) |

Isabella Elliott

(m. 1786; died 1826) |

| Children | 4, including Jane |

Thomas Bewick (born around August 11, 1753 – died November 8, 1828) was a famous English wood-engraver and writer about natural history. He was known for his amazing skill in creating detailed pictures using wood.

Early in his career, Thomas Bewick did many different jobs. He engraved cutlery (like knives and forks) and made wood blocks for advertisements. He also drew pictures for children's books. Over time, he started writing and publishing his own books. His beautiful pictures in A History of Quadrupeds became popular with adults too.

Thomas Bewick learned his craft as an apprentice to an engraver named Ralph Beilby in Newcastle upon Tyne. He later became a partner in the business and eventually took it over. Many talented artists learned from Bewick, including John Anderson, Luke Clennell, and William Harvey. They all became well-known painters and engravers themselves.

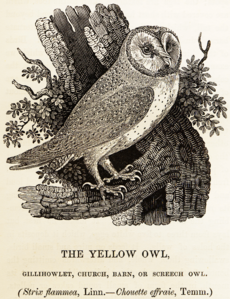

Bewick is most famous for his book A History of British Birds. People still admire it today for its detailed wood engravings. He was especially good at creating small, funny, and very detailed pictures called "tail-pieces." This book was like an early version of the bird guides we use today. He also illustrated many editions of Aesop's Fables throughout his life.

Many people consider Thomas Bewick the "founder of wood-engraving." He was the first to truly show what this art form could do. He used tools normally meant for metal engraving to cut hard boxwood across its grain. This made printing blocks that could be used with metal type. His method created much more detailed and lasting pictures than older woodcuts. This meant high-quality illustrations could be made at a low cost.

Contents

Bewick's Life Story

Thomas Bewick was born in a house called Cherryburn. It was in the village of Mickley, Northumberland, near Newcastle upon Tyne. He was born on August 10 or 11, 1753, but his birthday was always celebrated on the 12th. His parents were farmers who rented their land. His father, John, was in his forties when Thomas, the oldest of eight children, was born. John also rented a small coal mine nearby. Thomas went to school in the village of Ovingham.

Thomas was not very good at schoolwork. However, he showed a great talent for drawing from a very young age. He never had any formal art lessons. When he was 14, he became an apprentice to Ralph Beilby, an engraver in Newcastle. There, he learned to engrave on both wood and metal. This included putting names and family symbols on jewelry and cutlery.

In Beilby's workshop, Bewick engraved diagrams on wood for Charles Hutton. These pictures helped explain a book about measurement. After this, he focused mainly on wood engraving. In 1775, he won a prize from the Royal Society of Arts for a wood engraving. It was called "Huntsman and the Old Hound" from a book he was illustrating, Select Fables by the late Mr Gay.

In 1776, Bewick became a partner in Beilby's workshop. Their business did very well. It became the best engraving service in Newcastle. It was known for its high-quality work. In September 1776, Thomas went to London for eight months. He found the city to be rough and unfair, with rich and poor people living side by side. He did not like it there.

He returned to Newcastle as soon as he could. But his time in London helped him gain a wider reputation. It also gave him business experience and showed him new art styles.

In 1786, when he had enough money, he married Isabella Elliott. She was from Ovingham and had been his friend since childhood. They had four children: Robert, Jane, Isabella, and Elizabeth. After Thomas died, his daughters worked on his life story.

Thomas Bewick was described as a strong man, almost 6 feet tall. He was very brave. He was also known for his strong sense of right and wrong. He was one of the first people to speak out for the fair treatment of animals. He did not like it when horses' tails were cut short. He also disliked how performing animals, like bears, were treated. Most of all, he thought war was completely pointless. These ideas often appeared in his engravings. For example, he showed wounded soldiers returning from wars. He also showed animals with a gallows (a structure for hanging) in the background.

Bewick had at least 30 students who worked for him and Beilby. His younger brother John was his first student. Many of his students became famous engravers. These included John Anderson, Luke Clennell, William Harvey, and his own son, Robert Elliot Bewick.

In 1790, Bewick and Beilby published their History of Quadrupeds. It was meant for children but became popular with adults too. Its success made them think about a more serious book about natural history. Bewick spent several years engraving the wood blocks for Land Birds. This was the first part of A History of British Birds. Bewick knew a lot about the birds of Northumberland. So, he drew the pictures. Beilby was supposed to write the text, but he found it difficult. Bewick ended up writing most of the text himself. This caused an argument about who should be named as the author. In the end, only Bewick's name appeared on the title page.

It may be proper to observe, that while one of the editors of this work was engaged in preparing the Engravings, the compilation of the descriptions was undertaken by the other, subject, however, to the corrections of his friend, whose habits led him to a more intimate acquaintance with this branch of Natural History. – Land Birds, Preface.

The book was published in 1797 by Beilby and Bewick. It was an immediate success. Before this, Bewick also illustrated other books. After the success of his bird illustrations, Bewick started working on the second volume, Water Birds. But the disagreement over who wrote the book led to a final split with Beilby. Bewick had to pay a lot of money to end their partnership.

With help from his students, Bewick published the second volume, Water Birds, in 1804. He was the only author. He found managing the printers difficult. However, the book was as successful as the first volume.

In April 1827, a famous American naturalist and bird painter named John James Audubon visited Britain. He wanted to find a printer for his huge book, Birds of America. Bewick, who was 74 but still active, showed Audubon a woodcut he was working on. It showed a dog afraid of tree stumps that looked like devils in the dark. Bewick also gave Audubon a copy of his Quadrupeds for Audubon's children.

Bewick loved the music of Northumberland. He especially liked the Northumbrian smallpipes. He wanted to help promote this music and support the piper John Peacock. So, he encouraged Peacock to teach students. One of these students was Thomas's son, Robert. Robert's music books show what a piper played in the 1820s.

Bewick's last wood engraving was called Waiting for Death. It showed an old, skinny workhorse standing sadly by a tree stump. He had seen and sketched this horse when he was an apprentice. He died after a short illness on November 8, 1828, at his home. He was buried in Ovingham churchyard. His wife Isabella, who had died two years earlier, was buried nearby. His parents and brother John were also buried there.

Bewick's Work and Art

Engraving Technique

Thomas Bewick's art is considered the best example of his technique, now called wood engraving. This is because of his great skill and his special method. Unlike older woodcuts, his method involved carving against the grain of hard box wood. He used very fine tools that metal engravers normally used.

Boxwood cut across the end-grain is very hard. This allows for much finer details than in regular woodcuts. Since Bewick's time, this method has mostly replaced the basic woodcut. Also, wood engraving is a relief printing technique. This means the raised parts of the block are inked. It needs only low pressure to print an image. So, the blocks can be used for many thousands of prints. Importantly, they can be put together with letterpress (metal type) for text. This allows both pictures and text to be printed on the same page in one go. In contrast, copper plate engraving needs a special printing press with much higher pressure. Pictures have to be printed separately from the text, which costs a lot more.

Bewick was very good at observing nature. He had an amazing visual memory and sharp eyesight. This helped him create very accurate and tiny details in his wood engravings. This was both a strength and a weakness. If printed correctly, his pictures showed subtle clues about the animals' characters. They often had humor and feeling. He did this by carefully changing the depth of the engraved lines. This created actual shades of grey, not just black and white.

However, this detailed engraving made printing difficult. Printers had to use just the right amount of ink, mixed to the perfect thickness. They also had to press the block slowly and carefully to get a good result. This made printing slow and expensive. It also meant that readers often needed a magnifying glass to see the tiny details, especially in the miniature tail-pieces. But Bewick's work changed book illustration. Wood engraving became the main way to illustrate books for the next century. The quality of Bewick's engravings attracted many more readers than he expected. His Fables and Quadrupeds were originally meant for children.

Bewick worked with his apprentices, helping them develop their skills. So, while he didn't do every part of every illustration himself, he was always closely involved. As John Rayner explains:

some blocks would be drawn by one brother and cut by the other, the rough work would be done by pupils, who would also, if they showed aptitude, draw and finish designs—on the same principle as the schools of Renaissance painters; and we cannot ... be sure in all cases that the engravings ... are the work of Thomas Bewick from first to last, but he had a hand to a great extent in nearly all, and certainly had the last word in all of them.

Famous Engravings

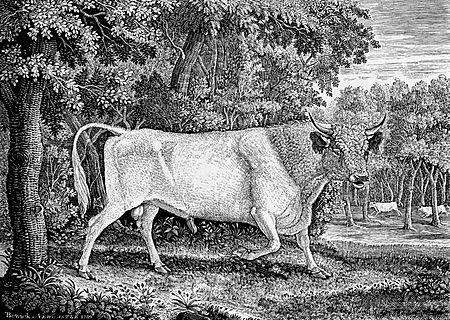

Some of his well-known works using his wood engraving technique include pictures for Oliver Goldsmith's Traveller and The Deserted Village. He also illustrated Thomas Parnell's Hermit and William Somervile's Chase. However, the most famous of all Bewick's prints is said to be The Chillingham Bull. Bewick made this very large engraving for Marmaduke Tunstall, a gentleman who owned land in Wycliffe.

Tail-pieces: Mini Stories

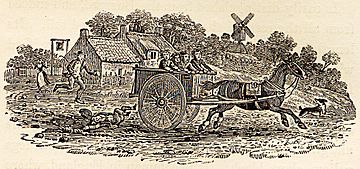

The "tail-pieces" were a special feature of Bewick's work. These are small engravings used to fill empty spaces on pages. For example, they would appear at the end of an animal's description in British Birds. Each picture is full of life and movement. They often tell a small story or have a moral lesson. They are always full of sympathy and careful observation. So, the images tell a "tale" as well as being at the "tail" ends of articles.

For example, the runaway cart picture is at the end of "The Sparrow-Hawk" section. It fills a 5 cm (2 inch) gap. Hugh Dixon explains:

The runaway cart is a wonderful mixture of action and danger. The boys have been playing in the cart and the horse has bolted; perhaps the dog's barking was the cause. The drawing of the wheel—an extraordinary depiction for its time—shows that the cart has gathered speed. One boy has already fallen and probably hurt himself. The others hang on shouting with fear. And why has it all happened? The carter with his tankard in his hand runs too late from the inn. Has he been distracted by the shapely girl? And is it an accident that the inn sign looks a little like a gallows?

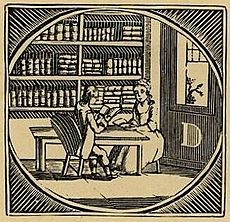

Bookplates

Bewick's workshop made many small, temporary items. These included letterhead paper, shop advertisements, and other business materials. Among these, his "bookplates" have lasted the best. Bewick's bookplates were illustrations made from engravings. They usually had the name or initials of the book's owner.

Aesop's Fables

Thomas Bewick illustrated different versions of Aesop's Fables throughout his life. The first one was for a bookseller in Newcastle, Thomas Saint, in 1776. This was during Bewick's time as an apprentice. Later, he and his brother John helped with a three-volume edition in 1784. They reused some pictures from the 1776 book.

Bewick then created a third edition of the fables. In 1812, while recovering from an illness, he started working on a large three-volume edition called The Fables of Aesop and Others. It was finally published in 1818. This book had three parts. The first part had some of Dodsley's fables with a short moral lesson. The second part had "Fables with Reflections." Each story was followed by a prose and verse moral, then a long reflection. The third part, "Fables in Verse," included fables from other sources.

Bewick designed the engravings on the wood first. Then, his apprentices cut them under his close watch. He would refine them if needed. This edition used a method Bewick had developed called "white-line" engraving. In this technique, the lines that should remain white are cut out of the woodblock.

A General History of Quadrupeds

A General History of Quadrupeds was published in 1790. It describes 260 different mammals from all over the world. This includes animals from the "Adive" to the "Zorilla". It is especially detailed about some domestic animals. The first entry describes the horse.

Bewick and Beilby found it hard to decide what animals to include. They also struggled with how to organize the entries. They wanted to arrange the animals in a scientific way. However, the systems of scientists like Linnaeus, Buffon, and John Ray often disagreed. Linnaeus's system even changed with every new edition of his work. So, they decided to put useful animals first. They believed these animals "materially contribute to the strength, the wealth, and the happiness of this kingdom."

The book's coverage of animals was a bit mixed. This was because of the sources Bewick used. He used his own knowledge of British animals. He also used scholarly books available at the time. These included George Culley's 1786 Observations on Livestock and John Caius's 1576 On English Dogs. Bewick also had a book by the Swedish naturalist Anders Sparrman. It was about his visit to the Cape of Good Hope during Captain Cook's trip from 1772 to 1776. So, animals from the Southern Cape appear a lot in the book. It was a lively mix, and the British public loved it right away. They liked the strong woodcuts, simple descriptions, and the mix of exotic animals with ones they knew.

A History of British Birds

A History of British Birds is Bewick's greatest work. His name is always linked to it. It was published in two volumes. The first, History and Description of Land Birds, came out in 1797. The second, History and Description of Water Birds, was published in 1804. A supplement was added in 1821. This book focuses specifically on British birds. It is also seen as the first modern field guide for birds.

Bewick knew a lot about animal habits. He learned this from his many trips into the countryside. He also included information from friends and local landowners. He used other natural history books of his time, like those by Thomas Pennant and Gilbert White. He also used a translation of Buffon's Histoire naturelle.

Many of the pictures from this book are often copied in other books and used as decorations. These are the small tail-pieces that Bewick put at the bottom of the pages. The worlds shown in these pictures are so tiny that you need a magnifying glass to see all the details. Each scene, as Adrian Searle writes, "is a small and often comic revelation." Each tiny image gives "enormous pleasure." Bewick "was as inventive as he was observant, as funny and bleak as he was exacting and faithful to the things he saw around him."

Bewick's biographer, Jenny Uglow, writes that:

Bewick appears to have had a faultless sense of exactly what line was needed, and above all where to stop, as if there were no pause for analysis or reflection between the image in the mind and the hand on the wood. This skill, which has made later generations of engravers pause in awe, could be explained as an innate talent, the je-ne-sais-quoi of "genius". But it also came from the constant habit of drawing as a child, the painstaking learning of technique as an apprentice ...

Bewick sometimes used his fingerprint as a signature. He would write "Thomas Bewick his mark" next to it. He also engraved his fingerprint in one of his tail-pieces. It looked as if it had accidentally smudged a tiny picture of a country scene with a cottage. Uglow notes that one critic thought Bewick might have meant we are looking at the scene through a playfully smudged window. It also draws attention to Bewick, the artist. Adrian Searle, writing in The Guardian, called the tiny work "A visual equivalent to the sorts of authorial gags Laurence Sterne played in Tristram Shandy, it is a marvellous, timeless, magical joke."

Tributes to Bewick

Even during his lifetime, poets wrote poems praising Bewick. William Wordsworth started his poem "The Two Thieves" (written in 1798) with the line "O now that the genius of Bewick were mine." He declared that if he had Bewick's talent, he would stop writing.

In 1823, Bewick's friend, Reverend J. F. M. Dovaston, wrote a sonnet (a type of poem) dedicated to him. It included these lines:

-

- Xylographer I name thee, Bewick, taught

By thy wood-Art, that from rock, flood, and tree

Home to our hearths, all lively, light and free

In suited scene each living thing has brought

As life elastic, animate with thought.

- Xylographer I name thee, Bewick, taught

Four years after Bewick died, a sixteen-year-old admirer named Charlotte Brontë wrote a poem of 20 verses. It was called "Lines on the celebrated Bewick." The poem described the different scenes she saw while looking through books illustrated by him. Later, the poet Alfred Tennyson wrote his own tribute. He left it on the first blank page of a copy of Bewick's History of British Birds. This book was found in Lord Ravenscroft's library:

-

- A gate and field half ploughed,

- A solitary cow,

- A child with a broken slate,

- And a titmarsh in the bough.

- But where, alack, is Bewick

- To tell the meaning now?

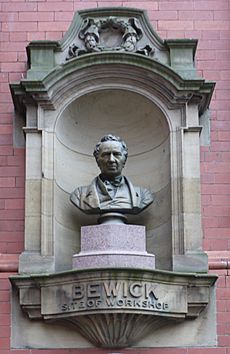

There are many portraits of Bewick. In 1825, the Literary and Philosophical Society asked Edward Hodges Baily to sculpt a marble statue of Bewick's head and shoulders. There are several copies of this statue. One is still at the Society itself. According to Uglow, when Bewick came to pose for the sculptor, he "strongly refused to be portrayed in a toga." Instead, he wore his normal coat and waistcoat. He even asked for some of his smallpox scars to be shown. Baily was so impressed with him that he gave Bewick a plaster model of the finished statue. A bronze copy is now in a niche (a small alcove) of the building that replaced his workshop. Another copy is at the British Museum. There is also a full-length statue of him on a former chemist's shop at 45 Northumberland Street in Newcastle.

Bewick's Legacy

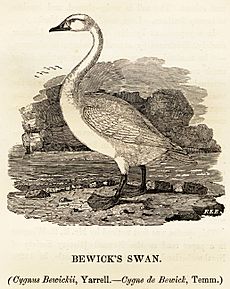

Bewick's fame grew throughout the 1800s. In 1830, William Yarrell named the Bewick's swan in his honor. Bewick's son Robert engraved this bird for later editions of British Birds.

The critic John Ruskin compared Bewick's detailed drawing to that of famous artists like Holbein and J. M. W. Turner. Ruskin wrote that the way Bewick engraved the feathers of his birds was "the most masterly thing ever done in woodcutting." Bewick's fame faded as illustrations became more common and mechanical. However, artists in the 1900s, like Gwen Raverat, continued to admire his skill. Works by artists such as Paul Nash and Eric Ravilious have been described as similar to Bewick's.

Hugh Dixon, thinking about Bewick and the landscape of North-East England, wrote:

Bewick's illustrated books, admired since they first appeared, gave him some celebrity in his own lifetime. His Memoir, published a generation after his death, brought about a new interest and a widening respect which has continued to grow ever since. The attraction to his contemporaries of Bewick's observations lay in their accuracy and amusement. Two centuries later these qualities are still recognised; but so, too, is the wealth and rarity of the historical information they have to offer.

Thomas Bewick Primary School, in West Denton in Newcastle upon Tyne, is named after him. Bewick's works are kept in important collections. These include the British Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum. Newcastle's City Library has a collection of his works and related items. This was given to the city by John William Pease in 1901. Bewick is remembered around Newcastle and Gateshead. Streets are named after him, and plaques mark his former homes and workshops.

See also

In Spanish: Thomas Bewick para niños

In Spanish: Thomas Bewick para niños

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |