Francis Willughby facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Francis Willughby

|

|

|---|---|

Portrait by Gerard Soest between 1657 and 1660

|

|

| Born | 22 November 1635 Middleton Hall, Warwickshire, England

|

| Died | 3 July 1672 (aged 36) Middleton Hall, Warwickshire, England

|

| Resting place | St. John the Baptist parish church, Middleton |

| Nationality | English |

| Alma mater | Trinity College, Cambridge |

| Known for | Ornithologiae Libri Tres |

| Spouse(s) |

Emma Barnard

(m. 1668) |

| Parents |

|

| Relatives | Thomas Willoughby, 1st Baron Middleton (son) Cassandra Willoughby, Duchess of Chandos (daughter) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Ornithology, ichthyology |

| Influences | John Ray |

Francis Willughby (born November 22, 1635 – died July 3, 1672) was an English scientist. He was especially interested in birds and fish. He also studied languages and games.

Francis was born and grew up at Middleton Hall, Warwickshire. He was the only son in a wealthy family. He studied at Trinity College, Cambridge. There, he was taught by John Ray, a naturalist and mathematician. Ray became his lifelong friend and colleague. After 1662, Ray lived with Willughby. This was because Ray lost his job for not signing a law called the Act of Uniformity. Willughby became a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1661 when he was 27.

Willughby, Ray, and other scientists like John Wilkins believed in a new way of studying science. They thought it was important to observe things and classify them. This was different from just trusting old ideas from Aristotle or the Bible. To do this, Willughby, Ray, and their friends went on many trips. They wanted to collect information and specimens. First, they traveled in England and Wales. Later, they went on a big tour of Europe. They visited museums, libraries, and private collections. They also studied local animals and plants. After their European trip, Willughby and Ray mostly lived and worked at Middleton Hall. Willughby married Emma Barnard in 1668. They had three children.

Willughby had been sick many times over the years. He sadly died from pleurisy in July 1672, when he was only 36. Because he died so young, John Ray had to finish the books they had planned together. Ray later published books about birds, fish, and invertebrates. These books were called Ornithologiae Libri Tres, Historia Piscium, and Historia Insectorum. The bird book was also published in English. These books had new and good ways to classify animals. They were very important in the history of life science. They influenced later natural history writers. They also helped Carl Linnaeus create his system of naming living things, called binomial nomenclature.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Francis Willughby was born at Middleton Hall, Warwickshire on November 22, 1635. He was the only son of Sir Francis Willoughby and Cassandra Ridgeway. His family was wealthy. Their main home was Wollaton Hall, in Nottingham. Francis went to Bishop Vesey's Grammar School and then Trinity College, Cambridge. He read many books. His library had about 2,000 books when he died. These included books on literature, history, and science.

Willughby started studying at Trinity College when he was 17. His teacher was James Duport. Duport shared the Willughby family's support for the king during the English Civil War. John Ray, who taught math at Trinity, arranged for Isaac Barrow to teach Willughby math. Willughby and Barrow became friends. In 1655, Barrow dedicated his book Euclid's Elements to Willughby and two other students.

Willughby earned his Bachelor of Arts degree in January 1656. He later received his Master of Arts degree in July 1660. In 1657, he joined Gray's Inn. This was common for wealthy men who might need to handle legal issues. Willughby and Ray worked together on science projects at Trinity. They made "sugar of lead" and extracted antimony. In 1663, Willughby, at age 27, became a founding Fellow of the Royal Society. He was nominated by Ray and John Wilkins. Wilkins became the head of Trinity College in 1660. In 1667, Ray also became a Fellow of the Royal Society. He did not have to pay the fee because he was not wealthy.

Scientific Journeys

In the late 1500s and early 1600s, Francis Bacon said that knowledge should come from observation and experiments. This was instead of just relying on old ideas. The Royal Society and its members, like Ray, Wilkins, and Willughby, wanted to use this new scientific method. This included traveling to collect specimens and information. Willughby helped Ray collect plants for his book Catalogus Plantarum circa Cantabrigiam Nascentium. This book was published in 1660.

Later that year, Ray and Willughby traveled through northern England. They visited the Lake District, the Isle of Man, and the Calf of Man. They saw a Manx shearwater chick there. Willughby then briefly visited the University of Oxford. He wanted to look at some rare natural history books.

Exploring England and Wales

In May 1662, Willughby, Ray, and Philip Skippon (Ray's student) started another journey. They went through Nantwich and Chester and west to Anglesey. They then went inland to Llanberis. There, they were shown a local lake fish called a torgoch. Willughby realized it was the same as the Windermere charr he had seen before. The group then went south through west Wales to Pembroke. They visited Bardsey Island along the way. They then traveled back along the Welsh south coast to Tenby. They saw many fish species there. At Aberavon, they were shown a rare black-winged stilt.

Willughby talked to Welsh speakers to study the language. He wanted to understand it in a systematic way. This study was never published, but it influenced later scholars. During this trip, Ray and Willughby decided to try and classify all living things. Ray mostly worked on plants, and Willughby worked on animals. The lists of species they made were used by Wilkins. He used them for a larger system published in 1668. This system was called An Essay towards a Real Character, and a Philosophical Language. Wilkins wanted to create a universal way to describe the natural world. Studying languages helped him create a logical system for his classifications.

Willughby and his friends separated when he became ill at Gloucester. His friends continued through the West Country to Land's End. When Willughby got better, he spent part of the summer birdwatching in Lincolnshire. Ray and Willughby later visited the West Country together in 1667. They returned through Dorset, Hampshire, and London.

European Adventures

In August 1662, Ray left his teaching job at Cambridge. He did not want to agree to the rules for Church of England priests. He was unemployed and had no money. But Willughby offered him a place to live and work at Middleton. Willughby wrote that he would be "Verie glad of your constant company and assistance in my studies."

In April 1663, Willughby, Ray, Skippon, and Nathaniel Bacon (another friend from Trinity) left for Europe. They had a plan and passports. Willughby's wealth made the trip possible. They wanted to visit museums, libraries, and private collections. They also wanted to study local animals and plants. Fish and bird markets were good places to find information and specimens. Everyone kept journals, but most of Willughby's are lost. Ray's book, Observations topographical, moral & physiological made in a journey through part of the Low-Countries, Germany, Italy and France, tells most of the story. It also includes Willughby's notes from Spain.

The travelers visited Brussels, the University of Leuven, Antwerp, Delft, The Hague, and Leiden's university and library. On June 5, they saw a group of cormorants, grey herons, and spoonbills at Zevenhuizen. Willughby studied a spoonbill chick he got there. The group continued north through Haarlem, Amsterdam, and Utrecht. Then they went to Strasbourg. Willughby bought a handwritten book there from its author, Leonhard Baldner. This book had paintings of birds, fish, and other animals.

Baldner was a successful former fisherman and naturalist. Like the Englishmen, he only wrote about what he saw. Frederick Slare translated the German text into English. Ray said in his book: "I have received much light and information from the Work of this poor man." He said Baldner helped him understand things better.

The group continued through Liège, Cologne, and Nuremberg. They arrived in Vienna on September 15 and stayed for several days. On September 24, they left for Venice. The journey through the Alps was hard. The mountain paths were bad, the weather was poor, and there was little food. They finally reached Venice on October 6. In Venice, Skippon listed 60 types of fish and 28 kinds of birds he saw in the markets.

The group stayed in Venice from October 6, 1663, to February 1, 1664. They also took a trip to Padua. There, they looked at medical procedures, including studying human bodies. They then traveled through northern Italy. They stopped in Ferrara, Verona, Bologna, Milan, and Genoa. In Bologna, they visited the public museum of Ulisse Aldrovandi. On April 15, 1664, they sailed to Naples from Livorno. Here, the group split up. Willughby and Bacon went to Rome. They stayed there in May, June, and July. Ray and Skippon went on to Sicily and Malta.

During their European journey, Willughby and Skippon especially studied languages. In Vienna, they visited collections and also studied Turkish and several Slavic languages. Their notes show comparison tables for seventeen languages. These included Basque, Armenian, and Persian.

Bacon got smallpox in Northern Italy. Willughby continued with only a servant to Montpellier, where Ray was already. Willughby entered Spain on August 31. He traveled through Valencia, Granada, Seville, Cordoba, and Madrid. He reached Irun on November 14. Willughby found little of scientific interest in Spain. He thought it was behind the times. He also did not like the land or the people.

Later Life and Passing

In Seville, Willughby received a letter saying his father was very ill. He quickly returned to Middleton, arriving just before Christmas 1664. His father died in December 1665. Francis then became responsible for the family estate. His relatives soon urged him to find a wife. But he waited, knowing it would limit his research.

In 1661, he sent the Royal Society the first paper describing the life cycle of insects. He and Ray also confirmed that caterpillars could be parasitized by ichneumon wasps. Willughby also raised and studied leaf-cutter bees. The bee he studied was later named after him: Willughby's leaf-cutter bee, Megachile willughbiella. Willughby was the first to clearly tell the difference between the honey buzzard and the common buzzard. In 2018, some suggested renaming the honey buzzard "Willughby's Buzzard" to honor him.

In 1668, Willughby married Emma Barnard. She was the daughter of Sir Henry Barnard. They had three children. Their first child, Francis, died at age nineteen. Their daughter Cassandra Willoughby married the Duke of Chandos. He supported the English naturalist Mark Catesby. Their second son, Thomas, became Baron Middleton in 1711.

Willughby and Ray continued their research, mostly on birds. They got help from Francis Jessop, another Trinity student. Jessop sent them specimens from the Peak District, including twite and red grouse. They were also the first to study how sap actively flows in birches.

Willughby had been sick many times between 1668 and 1671. Ray described these illnesses as "tertian ague" (likely malaria). The stress of defending a difficult inheritance dispute also put him under strain. On June 3, 1672, he became very ill again. He signed his will on June 24. He died on July 3. The cause of death was pleurisy, probably related to pneumonia. He was buried at St. John the Baptist parish church, Middleton. Ray, Skippon, and Jessop were there with the family. The church has a large memorial for Francis, his parents, and his son Francis. His second son, Thomas, put it there.

What Francis Willughby Studied

John Ray was one of five people chosen to carry out Willughby's will. Ray received £60 a year for life. He felt it was his duty to finish and publish Willughby's work on animals.

Birds: Ornithologiae Libri Tres

Willughby's Ornithology aimed to describe all known birds in the world. It had new features, like a good classification system. This system was based on a bird's body parts, such as its beak, feet, and size. It also had a dichotomous key. This helped readers identify birds by guiding them to the right group. The authors marked species they had not seen themselves with an asterisk. Willughby wanted to add "characteristic marks" to help with identification. The authors also avoided including extra information, like proverbs or historical references. The book was published in Latin in 1676 as Ornithologiae Libri Tres (Three Books of Ornithology).

The first part of the book introduced bird biology. It explained the new classification system and the identification key. The second and third parts described land birds and seabirds. Emma Willughby paid for the 80 metal-engraved pictures in the book. This is mentioned on the title page. The English version, The Ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton, came out in 1678. It included more material, like a section on fowling (hunting birds). Its success is not known, but it was very influential.

Fish: Historia Piscium

The next book, about fish, took many years to finish. Willughby's widow had remarried. Her new husband, Josiah Child, stopped Ray from looking at Willughby's papers. Also, there were many more known fish species than birds to describe. Ray was also working on his own History of Plants. The Historia Piscium was finally published in Latin in 1686. It was dedicated to Samuel Pepys, who had given money to the project. The book had four parts: an introduction to fish biology; cetaceans (like whales); cartilaginous fish (sharks and rays); and bony fish. The bony fish were further classified by their fins. The book had 187 pictures. Their cost made the book a financial problem for the Royal Society, which had mostly paid for it.

"Insects": Historia Insectorum

In the 1600s, the word "insect" meant more than it does today. So, the third main book, Historia Insectorum, included many other invertebrates. These included worms, spiders, and millipedes. It did not include molluscs, perhaps because Martin Lister was writing his own book on that group. Ray had similar problems finishing this book as he did with the fish book. However, in 1704, he saw notes prepared by Sir Thomas Willoughby and Thomas Man. Sir Thomas had moved into Wollaton Hall in 1687 and could access his father's papers.

Ray died in January 1705. Little happened with the Historia Insectorum until William Derham and the Royal Society finally published it in 1710. It was incomplete, had no pictures, and was only under Ray's name. However, Ray made it clear that Willughby did most of the insect research. The book had four parts. It started with a new classification system based on metamorphosis. The second part had the main species descriptions. Then came Ray's observations of butterflies and moths. An appendix by Martin Lister was about British beetles. Pictures prepared by Sir Thomas Willoughby were not used and are now lost.

Games and Probability

Willughby's Book of Games was not finished when he died. It was published in 2003 with explanations. He described many games and sports. These included cards, cockfighting, football, and word games. Some games are now unfamiliar, like "Lend me your Skimmer." For each game, he wrote the rules, equipment, and how to play. He also studied the first games babies and children play. He wrote a math section "On the rebounding of tennis balls." Like his science books, the Book of Games used observation, description, and classification.

A lost work, according to his daughter Cassandra, "shews the chances of most games." This might have been called The Book of Dice. Willughby was good at math. There is evidence that the lost text looked at probability in card and dice games.

Illustrations and Information Sources

The many pictures in the bird and fish books came from different places. Willughby had his own large collection of paintings he bought in Europe. He also borrowed pictures from friends like Skippon and Sir Thomas Browne. Many pictures were taken from earlier books by other writers. Some were based on Francis Barlow's oil paintings of birds in Charles II's aviary (bird house).

The pictures from earlier books came from many sources. These included books by Ulisse Aldrovandi, Pietro Olina, Georg Marcgrave, and Willem Piso. Willughby and Ray compared the pictures with real animals or specimens if possible. If not, they compared the pictures to each other to choose the most accurate one. Besides these authors, they used texts by Carolus Clusius, Adriaen Collaert, Gervase Markham, Juan Eusebio Nieremberg, and Ole Worm. Olina's Ucelliera seems to have been looked at again between the Latin and English versions of the Ornithology. The English version has a description of territorial behavior by the nightingale that was not in the Latin version.

Lasting Impact

Much of Willughby's written work is lost. His scientific equipment and most of his collections are also gone. What remains is mostly owned by his family and kept at the University of Nottingham. The Ornithology influenced Réamur in organizing his bird collection. It also influenced Brisson in his own bird work. Georges Cuvier noted the influence of the Historia Piscium. Carl Linnaeus, from 1735 onwards, used Willughby and Ray's books a lot in his Systema Naturae. This book is the basis of how we name species today.

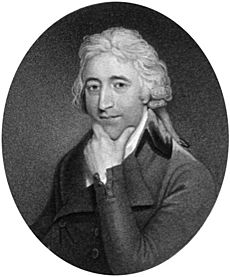

Because much of Willughby's work is lost and he died young, it's been debated how much he and Ray each contributed. Willughby's work was first well-regarded. But Ray's reputation grew over time. In 1788, the botanist James Edward Smith wrote that Willughby's contribution was overstated by Ray, who gave himself too little credit.

The view changed again when Charles E. Raven wrote Ray's biography in 1942. He saw Ray as the main partner. He said Willughby had "less knowledge, patience and judgment" than Ray. Raven thought Ray was a genius scientist. Raven did not know about the Willughby family papers at the University of Nottingham. Access to these and other new materials has led to a more balanced view today. Now, both men are seen as having made important contributions. Each showed his own strengths.

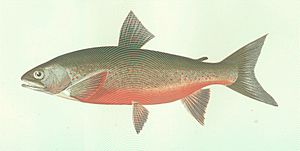

Willughby and Ray discovered several new species of birds, fish, and invertebrates. The names of the Windermere charr (Salvelinus willughbii), Willughby's leaf-cutter bee (Megachile willughbiella), and the plant genus Willughbeia all honor Francis Willughby. However, Willughby and Ray's main influence came from their three books. The Ornithology was especially important. These books focused on systematic description and classification. Even Willughby's own collection of 170 pictures and nature paintings seems to have been meant to show the order of nature.

Images for kids

-

In South Wales, Willughby and Ray saw a rare black-winged stilt shown here in the Ornithologiae Libri Tres as "Himantopus".

-

A room in the Palazzo Publico, Bologna, visited by Willughby's group to see the collections of Ferdinando Cospi and Ulisse Aldrovandi.

-

Plate XLIII from Samuel Pepys's hand-coloured copy of the Ornithology

-

Willughby studied this leaf-cutter bee, named by Kirby in 1802 as Megachile willughbiella.

-

Willughby is believed to have studied probability with respect to card games. This 17th-century Popish Plot deck was engraved by Francis Barlow, whose bird paintings were the basis of some of the illustrations in the Ornithology.

-

Windermere or Willughby's charr, Salvelinus willughbii

-

James Edward Smith wrote in 1788 that Willughby's contribution was overstated.

See also

In Spanish: Francis Willughby para niños

In Spanish: Francis Willughby para niños

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |