Samuel Pepys facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Samuel Pepys

|

|

|---|---|

Portrait of Samuel Pepys by J. Hayls.

Oil on canvas, 1666. |

|

| Born | 23 February 1633 |

| Died | 26 May 1703 (aged 70) |

| Resting place | St Olave's, London |

| Known for | Diary |

| Spouse(s) | Elisabeth Marchant de St Michel |

Samuel Pepys (born February 23, 1633 – died May 26, 1703) was an important English government worker. He worked for the Admiralty, which managed the navy. He was also a Member of Parliament, meaning he helped make laws. Pepys is most famous for the secret diary he kept.

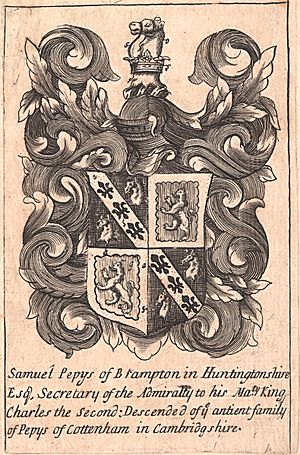

Pepys became the Chief Secretary to the Admiralty. He worked for King Charles II and later for King James II. Even though Pepys had no experience at sea, he became successful. He achieved his high position through hard work, his talent for managing things, and help from powerful friends.

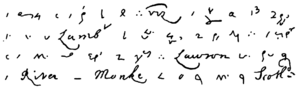

His detailed private diary was written between 1660 and 1669. It was first published in the 1800s. This diary is a very important primary source for understanding the English Restoration period. It mixes Pepys' personal thoughts with what he saw happening around him. He wrote about big events like the Great Plague of London, the Second Dutch War, and the Great Fire of London.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Samuel Pepys was born in London on February 23, 1633. His father, John Pepys, was a tailor. His mother, Margaret Pepys, was the daughter of a butcher. Samuel was the fifth of 11 children. However, many children died young back then. Soon, he became the oldest child in his family.

He was baptized at St Bride's Church on March 3, 1633. As a baby, Pepys lived for a while just north of London. Around 1644, he went to Huntingdon Grammar School. After that, he studied at St Paul's School in London from about 1646 to 1650. He even saw King Charles I being executed in 1649.

In 1650, Pepys went to the University of Cambridge. He received scholarships to help him pay for his studies. He started at Magdalene College in October 1650 and earned his degree in 1654.

Around 1654 or 1655, he began working for Sir Edward Montagu. Montagu was a relative of his father and later became the Earl of Sandwich. When Pepys was 22, he married 14-year-old Elisabeth de St Michel. She came from a French family who had moved to England. They had a religious wedding in October 1655 and a civil ceremony in December 1655.

Samuel Pepys' Famous Diary

On January 1, 1660, Samuel Pepys started writing his diary. He wrote about his daily life for almost ten years. This diary is over a million words long. Many people think it is Britain's most famous diary. Pepys is called one of the greatest diarists ever. This is because he was very honest about his own faults. He also accurately wrote about everyday life in Britain and major events in the 1600s.

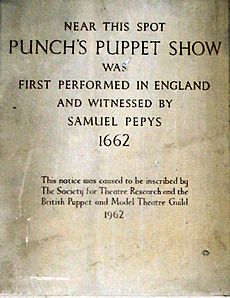

Pepys wrote about the royal court and the theater. He also wrote about his home life. He included details about important political and social events. Historians use his diary to understand what life was like in London in the 1600s. Pepys consistently wrote about his money, when he woke up, the weather, and what he ate. He wrote about his new watch, which had an alarm. This was a new invention at the time. He also wrote about a visitor from the countryside who didn't like London because it was too crowded. He even wrote about his cat waking him up early.

Pepys' diary is one of the few sources that gives so many details about the daily life of a middle-class man in the 17th century. He even described the lives of his servants, like Jane Birch.

Besides daily activities, Pepys also wrote about the big events happening in his country. His diary gives a firsthand look at the English Restoration. It includes detailed accounts of major events from the 1660s. These include the Second Anglo-Dutch War, the Great Plague of London in 1665, and the Great Fire of London in 1666. His descriptions of the Plague and Fire are very vivid and show his compassion for people.

Pepys stopped writing his diary in 1669. His eyesight was bothering him. He worried that writing in dim light was hurting his eyes. He hinted that he might have others write for him. But this would mean losing his privacy. He never went through with those plans. Pepys lived for another 34 years and did not go blind. However, he never started writing his diary again.

The Great Plague of London

Outbreaks of the plague were common in London. Major epidemics had happened in 1592, 1603, 1625, and 1636. Pepys was not among the people most at risk. He did not live in crowded housing. He did not often mix with the poor. He also did not have to keep his family in London during a crisis. It was not until June 1665 that the plague became very serious. So, Pepys' activities in the first five months of 1665 were not much affected. One writer, Claire Tomalin, said that 1665 was one of the happiest years of Pepys' life. He worked very hard that year and quadrupled his money.

Still, Pepys was worried about the plague. He chewed tobacco because he thought it would protect him from getting sick. Pepys also suggested that the Navy Office should move to Greenwich. But he offered to stay in London himself. He was proud of how brave he was. Meanwhile, Elisabeth Pepys was sent to Woolwich. She did not return home until January 1666. She was shocked by the sight of St Olave's churchyard. Three hundred people had been buried there.

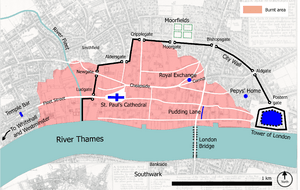

The Great Fire of London

In the early morning of September 2, 1666, Pepys was woken by his maid, Jane. She had seen a fire in the Billingsgate area. He thought the fire was not very serious and went back to bed. Soon after, his servant returned. She reported that 300 houses were destroyed. She also said that London Bridge was in danger. Pepys went to the Tower of London to get a better view. Without going home, he took a boat. He watched the fire for over an hour.

In his diary, Pepys wrote about what he saw:

I went down to the water-side, and got a boat. I went through the bridge and saw a terrible fire. Poor Michell's house, as far as the Old Swan, was already burned. The fire was spreading fast. In a very short time, it reached the Steeleyard while I was there. Everyone was trying to move their belongings. They were throwing them into the river or putting them onto boats. Poor people stayed in their houses until the fire touched them. Then they ran into boats or climbed from one set of stairs by the water to another. And among other things, the poor pigeons did not want to leave their homes. They flew around the windows and balconies until some of them were burned, their wings, and fell down. I stayed and in an hour saw the fire rage everywhere. No one, to my sight, was trying to put it out. They were only moving their goods and leaving everything to the fire. I saw it reach the Steele-yard. The wind was very strong and pushed the fire into the City. Everything, after such a long dry spell, was burning easily, even the stones of churches. And among other things, the poor church steeple where pretty Mrs.---- lives, and where my old school-friend Elborough is the priest, caught fire at the very top and burned until it fell down...

—Diary of Samuel Pepys, Sunday, September 2, 1666

The wind was pushing the fire west. So, Pepys ordered his boat to go to Whitehall. He was the first person to tell the king about the fire. Pepys told the king that houses should be pulled down to stop the fire. The king agreed. He told Pepys to go to the Lord Mayor, Thomas Bloodworth. Pepys was to tell him to start pulling down houses. Pepys took a coach back to St Paul's Cathedral. Then he walked through the burning city. He found the Lord Mayor, who said, "Lord! what can I do? I am tired: people will not obey me. I have been pulling down houses; but the fire catches us faster than we can do it." At noon, Pepys went home. He had "an extraordinarily good dinner, and as merry, as at this time we could be." Then he went back to watch the fire. Later, he returned to Whitehall. He then met his wife in St James's Park. In the evening, they watched the fire from the safe area of Bankside. Pepys wrote that "it made me weep to see it." When he got home, Pepys met his clerk, Tom Hayter, who had lost everything. Hearing that the fire was getting closer, Pepys started to pack his belongings by moonlight.

A cart arrived at 4 a.m. on September 3. Pepys spent most of the day moving his things. Many of his valuable items, including his diary, were sent to a friend. At night, he "fed upon the remains of yesterday's dinner, having no fire nor dishes, nor any opportunity of dressing any thing." The next day, Pepys continued to move his belongings. He believed his home was in great danger. So, he suggested calling men from Deptford to help pull down houses. He wanted them to defend the king's property. He described the chaos in the city and his own efforts to save his goods:

Sir W. Pen and I went to Tower-street. The fire was burning three or four doors beyond Mr. Howell's house. His goods, poor man, his trays, and dishes, shovels, etc., were thrown all along Tower-street in the gutters. People were working with them from one end to the other. The fire was coming on in that narrow street, on both sides, with great fury. Sir W. Batten did not know how to move his wine. He dug a pit in the garden and put it there. I took the chance to put all the papers from my office that I could not move. And in the evening Sir W. Pen and I dug another pit. We put our wine in it; and I put my Parmesan cheese, as well as my wine and some other things.

—Diary of Samuel Pepys, Tuesday, September 4, 1666

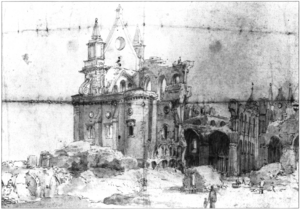

Pepys had been sleeping on his office floor. On Wednesday, September 5, his wife woke him at 2 a.m. She told him the fire had almost reached All Hallows-by-the-Tower. It was at the bottom of Seething Lane. He decided to send her and his gold, about £2,350, to Woolwich. In the next few days, Pepys saw stealing, disorder, and disruption. On September 7, he went to Paul's Wharf. He saw the ruins of St Paul's Cathedral, his old school, his father's house, and the house where he had a surgery. Despite all this destruction, Pepys' house, office, and diary were saved.

Personal Interests and Royal Society

Pepys' diary tells us a lot about his personal life. He enjoyed wine, plays, and spending time with friends. He also thought a lot about his money and his place in the world. He was always curious and often followed his interests. Sometimes, he would decide to work harder and spend less time on fun. For example, on New Year's Eve, 1661, he wrote: "I have just made a serious promise to stop going to plays and drinking wine…" But the diary shows he didn't always keep his promises. By February 17, he wrote, "Here I drank wine out of necessity, being sick for the want of it."

Pepys was one of the most important government workers of his time. He was also a very cultured man. He loved books, music, theater, and science. Besides English, he spoke French well. He also read many books in Latin. His favorite writer was Virgil. He was very passionate about music. He composed music, sang, and played instruments for fun. He even arranged music lessons for his servants. He played the lute, viol, violin, flageolet, recorder, and spinet. He was also a good singer. He sang at home, in coffee houses, and even in Westminster Abbey. He and his wife took flageolet lessons. He also taught his wife to sing and paid for her dancing lessons.

Pepys was also an investor in the Company of Royal Adventurers Trading to Africa. This company had the special right to trade along the west coast of Africa. They traded in gold, silver, ivory, and slaves.

Samuel Pepys and Science

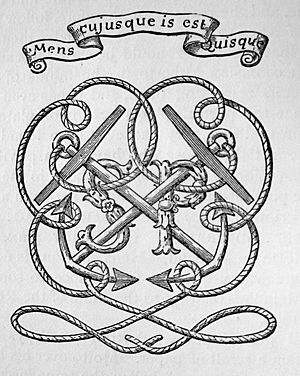

Pepys became a member of the Royal Society in 1665. This is a famous group for scientists. He was its President from December 1, 1684, to November 30, 1686. Isaac Newton's famous book, Principia Mathematica, was published during this time. Pepys' name is on the title page of the book.

There is a probability problem called the "Newton–Pepys problem". It came from letters between Newton and Pepys. They discussed whether it was more likely to roll at least one six with six dice, or at least two sixes with twelve dice. It was recently discovered that Newton's gambling advice to Pepys was correct. However, the logical reason Newton gave was not quite right.

Retirement and Legacy

Pepys was put in prison twice, in 1689 and 1690. This was because he was suspected of supporting the old king, James II. But no charges were ever proven against him. After he was released, he stopped working in public life at age 57. Ten years later, in 1701, he moved out of London. He went to a house in Clapham owned by his friend William Hewer. Clapham was countryside back then, but now it's part of London.

Pepys lived there until he died on May 26, 1703. He had no children. He left all his belongings to his nephew, John Jackson. Pepys was buried next to his wife in St Olave's Church in London.

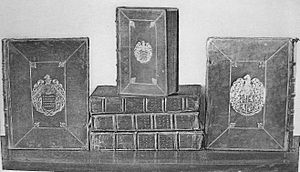

The Pepys Library

Samuel Pepys loved books his whole life. He carefully collected many books, handwritten papers, and prints. When he died, he had over 3,000 books. These included his famous diary. All his books were carefully listed and organized. His collection is one of the most important private libraries from the 1600s that still exists.

The most important items in the library are the six original handwritten volumes of Pepys' diary. But there are other amazing things too, such as:

- Very early printed books by famous printers like William Caxton.

- Sixty medieval handwritten books.

- The Pepys Manuscript, a music book from the late 1400s.

- Naval records, like two 'Anthony Rolls'. These show ships of the Royal Navy from around 1546, including the Mary Rose.

- Sir Francis Drake's personal almanac.

- Over 1,800 printed ballads, which is one of the best collections ever.

Pepys made very clear instructions in his will for how his book collection should be kept. His nephew, John Jackson, died in 1723. Then, the collection was moved to Magdalene College, Cambridge, exactly as Pepys wanted. You can still see it there in the Pepys Library. The gift included all the original bookcases. Pepys even gave detailed instructions that the books should be "strictly reviewed and, where found requiring it, more nicely adjusted."

The Ephemera Society uses Pepys' picture as their symbol. They call him "the first general ephemerist." This means he was one of the first people to collect everyday printed items. Two large albums of these items saved by Pepys are in his library.

Images for kids

-

A short letter from Samuel Pepys to John Evelyn in Deptford. It was written on October 16, 1665, and talks about "prisoners" and "sick men" during the Second Dutch War.

-

Dutch Attack on the Medway, June 1667 by Pieter Cornelisz van Soest, painted around 1667. The captured ship Royal Charles is on the right side.

-

Samuel Pepys painted by Sir Godfrey Kneller in 1689.

See also

In Spanish: Samuel Pepys para niños

In Spanish: Samuel Pepys para niños

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |