Recorder (musical instrument) facts for kids

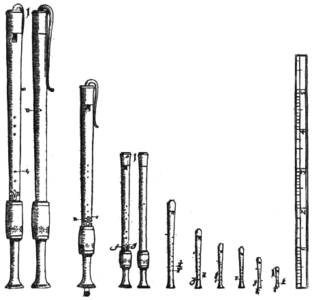

Various recorders (second from the bottom disassembled into its three parts)

|

|

| Woodwind | |

|---|---|

| Other names | See § Other languages |

| Classification | |

| Hornbostel–Sachs classification | 421.221.12 (Flute with internal duct and finger holes) |

| Playing range | |

| Soprano recorder: C5–D7(G7) | |

| Related instruments | |

|

|

| Musicians | |

| Recorder players | |

The recorder is a type of woodwind musical instrument. It belongs to a group called internal duct flutes. This means it's a flute with a special whistle-like mouthpiece. You can tell a recorder apart from other flutes because it has a thumb-hole for your top hand. It also has seven finger-holes: three for your top hand and four for your bottom hand. It's a very important flute in Western classical music.

Recorders come in many sizes. Their names and musical ranges are similar to different singing voices. The most common sizes today are the soprano (also called descant), alto (also called treble), tenor, and bass. Soprano recorders play the highest notes, starting at C5. Alto recorders start at F4, tenor at C4, and bass at F3.

Long ago, recorders were made from wood or ivory. Today, professional recorders are almost always made of wood, often boxwood. Recorders for students are usually made of plastic. Recorders have different shapes inside and out. But they all use a special way of playing called forked fingerings.

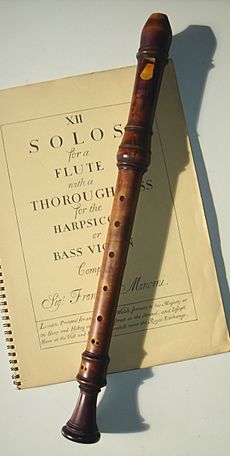

The recorder first appeared in Europe in the Middle Ages. It was very popular during the Renaissance and Baroque periods. But it wasn't used much in the Classical and Romantic times. In the 1900s, it became popular again. This was part of a movement to play music the way it sounded long ago. Now, it's a popular instrument for hobbies and schools. Many famous composers wrote music for the recorder, like Handel and Bach. Its sound is often called clear and sweet. People used to connect its sound with birds and shepherds.

Contents

- What's in a Name?

- Different Kinds of Recorders

- How Recorders Are Made

- How the Recorder Makes Sound

- How to Play the Recorder

- = Basic Fingerings

- Recorder History

- Recorders in Schools

- Recorder Groups

- Images for kids

- See also

What's in a Name?

The instrument has been called "recorder" in English since at least the 1300s. The first time we see the word "recorder" was in 1388. It was in the records of the Earl of Derby, who later became King Henry IV. The record mentioned "one pipe called 'Recordour'".

By the 1400s, the name appeared in English books. For example, in John Lydgate's Temple of Glas (around 1430), he wrote about "little shepherds fluting all day long... on these small recorders, on flutes."

Where Did the Name "Recorder" Come From?

The name recorder comes from the Latin word recordārī. This word means "to remember" or "to call to mind". It came to English through the French word recorder. This French word meant "to remember, to learn by heart, to repeat, or to play music".

The connection between remembering and playing music comes from medieval performers called jongleurs. These performers learned poems by heart and recited them. Sometimes they added music. The English verb "record" (meaning to play music) didn't appear until the 1500s. This was long after the instrument was named. So, the recorder wasn't named because it sounded like birds.

"Flute" vs. "Recorder"

In 1673, French musicians brought the Baroque recorder to England. They made its French name, flute douce (sweet flute), popular. Or they just called it "flute." Before this, "flute" usually meant the transverse flute (played sideways).

Until about 1695, both "recorder" and "flute" were used. But from 1673 to the 1720s in England, "flute" usually meant recorder. As the transverse flute became more popular, English speakers started adding words to "flute." They called the recorder the "common flute" or "English flute." The transverse flute was called the "German flute."

Recorder Names in Other Languages

In most European languages, the first word for the recorder was simply the word for "flute." Even today, the word "flute" can mean a recorder, a modern concert flute, or other flutes. Around the 1530s, people started adding words to specify the recorder.

For example, in Italian, musical scores until the mid-1700s called the recorder flauto. The transverse flute was called flauto traverso. This difference has caused confusion for musicians today.

Different Kinds of Recorders

Since the 1400s, many sizes of recorders have been made. But clear names and ways to write music for them weren't set until the 1900s.

Modern Recorders and Their Names

Today, recorder sizes are named after different singing voices. This helps show how their pitches relate to each other. When many recorders play together, they are called "consorts." Recorders are also often named by their lowest note, like "recorder in F."

The most common modern recorders are:

- Sopranino (highest)

- Soprano (also called descant)

- Alto (also called treble)

- Tenor

- Bass

- Great Bass (lowest)

When composers write new music for the recorder, they often use soprano, alto, tenor, and bass recorders. Sometimes sopranino and great bass are also used.

How Recorder Music Is Written

Modern recorder music is written at the pitch it sounds.

- Alto, tenor, and contrabass recorders play the notes as they are written.

- Sopranino, soprano, bass, and great bass recorders usually have their music written an octave (eight notes) lower than they actually sound. This makes the music easier to read.

Sometimes, special octave clefs are used to show the actual sounding pitch.

Recorders from the Past

The first known mention of a "pipe called Recordour" was in 1388. In the past, recorders played vocal music or parts written for other instruments. Players often had to choose the right recorder for music not specifically written for it.

In the 1500s, recorder consorts were often tuned in fifths. This means that recorders could be in different keys like B-flat, F, C, G, D, A, or even E. But usually, only three or four different sizes played together. These recorders were treated like "transposing instruments." This means the written notes were different from the actual sounding notes.

The alto recorder in F4 became the standard recorder during the Baroque period. In England in the 1600s, smaller recorders were named based on their relationship to the alto. They were called "third flute" (A4), "fifth flute" (soprano; C5), "sixth flute" (D5), and "octave flute" (sopranino; F5).

How Recorders Are Made

Recorders have always been made from hard woods and ivory. Since the recorder became popular again, plastics are also used to make many recorders.

Today, many different hardwoods are used for the main body of recorders. The "block" inside the recorder is often made of red cedar. This wood resists rot, absorbs water, and doesn't expand much when wet. Some new recorders even use special ceramics for the block.

Bigger Recorders

Some recorders are so large that a player's hands can't reach all the holes. Or the holes are too big to cover with fingers. For these, keys are added to cover the holes. Keys also allow makers to design longer instruments with bigger holes. Keys are most common on recorders larger than the alto. Recorders bigger than the tenor usually need at least one key.

When playing a very large recorder, you might not be able to reach the mouthpiece and the keys at the same time. A bocal (a curved tube) can be used to blow air into the recorder. This lets the player keep a comfortable hand position. Some large recorders have a bent shape, called "knick" or bent-neck recorders. This brings the mouthpiece closer to the finger holes.

New Recorder Designs

Some new recorder designs are being made today.

- Recorders with a square shape are cheaper to make and can be larger.

- Some new designs aim for a wider range of loud and soft sounds. They also have stronger low notes. This helps them be heard better in concerts.

- Recorders that can play a note a semitone lower than usual are also becoming available. These can play a full three octaves in tune.

German Fingering

In the early 1900s, Peter Harlan created a recorder with what seemed like simpler fingerings. This was called German fingering. On a German fingering recorder, the fifth hole is smaller than the fourth hole. On older "Baroque" recorders, the fourth hole is smaller than the fifth.

The main difference is for the note F (on a soprano recorder). With German fingering, it's simpler to play. But this makes many other notes sound out of tune. German fingering was popular in Germany in the 1930s. But it quickly became less used in the 1950s. People realized its limits as the recorder was taken more seriously. Today, German fingering recorders are mostly made for teaching beginners.

Recorder Pitch

Most modern recorders are tuned to A=440 Hz. This is the standard pitch for many instruments. But serious players and professionals often use other pitches. For Baroque music, A=415 Hz is common. For older music, A=440 Hz or A=466 Hz are used. These different pitches reflect how tuning varied throughout history.

A=415 Hz (a semitone lower) and A=466 Hz (a semitone higher) are useful. They let recorder players play with harpsichords or organs that can change their pitch. Some recorder makers even offer instruments with parts that can be swapped to play at different pitches.

How the Recorder Makes Sound

Making the Basic Sound

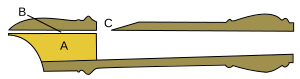

The recorder makes sound like a whistle or an organ flue pipe. When you blow into the recorder, air goes into a narrow channel called the windway (B). This air stream then hits a sharp edge called the labium (C). The air stream quickly moves above and below the labium. This creates sound waves inside the recorder's tube. The way the air vibrates inside the tube creates the pitch you hear.

Like all woodwind instruments, the air inside the recorder vibrates in different ways. These are called "modes of vibration" or overtones. The lowest and usually loudest vibration is the main pitch. Other pitches are harmonics or overtones. Players describe notes by how many vibration points (nodes) are in the air column. Notes with one node are in the first register. Notes with two nodes are in the second register, and so on.

How Air Affects Sound

The speed of the air you blow affects the recorder's pitch. Generally, blowing faster makes the pitch higher. Blowing too hard can make the note jump to a higher register. This is called "overblowing."

The way the recorder is shaped inside (its "voicing") also affects the air stream. The player can control the speed and smoothness of the air using their diaphragm and throat.

How Fingers Affect Sound

The finger holes, when covered or partly covered, change the pitch.

- When you lift fingers from the bottom holes upwards, the sounding length of the instrument gets shorter. This makes the pitch higher. For example, covering all holes (01234567) makes the lowest note. Lifting the bottom finger (0123456) makes a higher note.

Recorders also use forked fingerings. This is when you cover some holes below an open hole. For example, 0123 56 is a forked fingering because hole 4 is open, but holes 5 and 6 are covered. Forked fingerings allow for smaller changes in pitch and sound color.

Partially covering holes is also very important. This is called "leaking," "shading," or "half-holing."

- The thumb hole (hole 0) is often partly opened. This helps higher notes sound clearly at lower air pressures.

- Partially opening a covered hole makes the pitch higher.

- Partially closing an open hole makes the pitch lower. This technique helps players play in tune.

Double Holes

Many modern "Baroque" recorders have "double holes" for the last two fingers (holes 6 and 7). This means each finger covers two smaller holes. By covering one or both of these smaller holes, a player can play notes that are a semitone or minor third above the lowest note. Older recorders had single holes, and these notes were harder to play.

Covering the Bell

The open end of the recorder (the "bell") can be covered. This creates extra notes or special effects. Players usually do this by touching the end of the recorder to their leg or knee. Some recorders have a special "bell key" that a finger can use to cover the bell. Covering the bell can extend the recorder's range of notes.

How to Play the Recorder

Even though recorders have changed over 700 years, the basic way to play them is similar. Much of what we know comes from old books written between the 1500s and 1700s.

Holding the Recorder

You hold the recorder with both hands. Your fingers cover the holes or press the keys. Your lower hand uses four fingers. Your upper hand uses the index, middle, and ring fingers, plus the thumb. In modern playing, the right hand is usually the lower hand, and the left hand is the upper hand.

The recorder rests on your lips, which gently seal around the mouthpiece. Your lower hand's thumb also helps support it. Larger recorders might have a thumb rest or a neck strap for extra support. They might also use a bocal.

Recorders are usually held at an angle, somewhere between straight up and flat. This depends on the recorder's size and your preference.

Using Your Fingers

| Fingers | Holes |

|---|---|

|

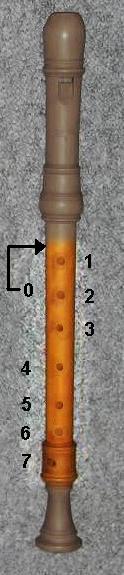

You make notes by covering the holes while blowing. The holes on the front are numbered 1 to 7, starting from the top. The thumb hole is hole 0. The simplest way to play higher notes is to lift fingers one by one, starting from the bottom. But in reality, you often half-cover holes or use special fingerings.

Forked Fingerings

A forked fingering means an open hole has covered holes below it. For example, to play F-sharp on a soprano recorder (0123 56), hole 4 is open, but holes 5 and 6 are covered. Forked fingerings allow for smaller pitch changes. They can also create slightly different sound colors.

Partially Covering Holes

Partially covering holes is a key part of playing the recorder. This is also called "leaking," "shading," or "half-holing." For the thumb hole, it's called "pinching."

The thumb hole helps you play higher notes. When you partly open it, the air inside the recorder vibrates differently, allowing higher notes to sound. You can partly open the thumb hole by sliding or rolling your thumb off it. You can also partly open other holes by sliding or lifting your fingers slightly.

Generally, partly opening a covered hole makes the note higher. Partly closing an open hole makes the note lower. This helps you play in tune.

Holes 6 and 7

Most modern "Baroque" recorders have "double holes" for the last two fingers (holes 6 and 7). This means each finger covers two smaller holes. By covering one or both of these, you can play notes a semitone (half step) above the lowest note. On older recorders with single holes, these notes were harder to play.

Covering the Bell

You can cover the open end of the recorder (the "bell") to make extra notes or effects. Since your hands are busy, you usually do this by touching the end of the recorder to your leg or knee. Some recorders have a special key for this. Covering the bell can extend the recorder's range.

Using Your Breath

The speed of the air you blow affects the recorder's pitch and loudness. Faster air generally makes a higher pitch. So, blowing harder can make a note sound sharp. Blowing too gently can make it sound flat. Knowing this helps you play in tune with other instruments. Blowing much harder can lead to "overblowing," where the note jumps to a higher pitch.

Breathing for Recorder

Playing the recorder needs very little air pressure. This is different from instruments like trumpets or clarinets. So, recorder players need to produce long, steady streams of air with low pressure. Breathing technique for the recorder focuses on controlling the release of air.

Tongue, Mouth, and Throat

Using your tongue to start and stop the air is called "articulation." The tongue helps control how a note starts (the "attack") and how long it lasts. Articulations are like consonant sounds. You can use almost any consonant sound you make with your tongue, mouth, and throat.

Common articulation patterns include:

- "du du du du" (using the tip of the tongue, "single tonguing")

- "du gu du gu" (alternating tip and back of tongue, "double tonguing")

- "du g'll du g'll" (using tip and sides of tongue, "triple tonguing")

The shape of your mouth and throat (like making vowel sounds) also affects the air. This changes the sound of the recorder.

Coordinating Fingers and Breath

You must coordinate your fingers and tongue. The start of each note should match your finger movements. Fingers move quickly in the tiny silence created by the tongue stopping the air.

Both your fingers and your breath control the recorder's pitch. Coordinating them is key to playing in tune and with different loudnesses and sound colors. For example, if you slowly increase breath pressure and slightly shade holes, you can increase volume without changing pitch.

= Basic Fingerings

| Recorder fingerings (English): Lowest note through the nominal range of 2 octaves and a sixth | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tuned in F |

Tuned in C |

Hole 0 |

Hole 1 |

Hole 2 |

Hole 3 |

Hole 4 |

Hole 5 |

Hole 6 |

Hole 7 |

Hole 0 |

Hole 1 |

Hole 2 |

Hole 3 |

Hole 4 |

Hole 5 |

Hole 6 |

Hole 7 |

Hole 0 |

Hole 1 |

Hole 2 |

Hole 3 |

Hole 4 |

Hole 5 |

Hole 6 |

Hole 7 |

End hole 8 |

||||||||

| F | C | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ◐ | ● | ○ | ○ | ● | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ||||||||

| F♯/G♭ | C♯/D♭ | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ◐ | ○ | ● | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ◐ | ● | ○ | ● | ● | ○ | ● | ● | ● | ||||||||

| G | D | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ◐ | ● | ○ | ● | ● | ○ | ● | ● | ○ | ||||||||

| G♯/A♭ | D♯/E♭ | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ◐ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ○ | ◐ | ○ | ● | ● | ○ | ● | ● | ○ | ○ | ||||||||

| A | E | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ○ | ○ | ◐ | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ○ | ○ | ◐ | ○ | ● | ● | ○ | ● | ● | ○ | ● | ||||||||

| A♯/B♭ | F | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ○ | ● | ● | ◐ | ● | ● | ● | ● | ○ | ● | ○ | ◐ | ● | ● | ○ | ● | ● | ○ | ○ | ● | ||||||||

| B | F♯/G♭ | ● | ● | ● | ● | ○ | ● | ● | ○ | ◐ | ● | ● | ● | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ | ◐ | ● | ● | ○ | ● | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ||||||||

| C | G | ● | ● | ● | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ◐ | ● | ● | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ◐ | ● | ○ | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ||||||||

| C♯/D♭ | G♯/A♭ | ● | ● | ● | ○ | ● | ● | ◐ | ○ | ◐ | ● | ● | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ◐ | ● | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ | ● | ● | ● | ||||||||

| D | A | ● | ● | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ◐ | ● | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ◐ | ● | ○ | ● | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ||||||||

| D♯/E♭ | A♯/B♭ | ● | ● | ○ | ● | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ◐ | ● | ● | ○ | ● | ● | ● | ○ | |||||||||||||||||

| E | B | ● | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ◐ | ● | ● | ○ | ● | ● | ○ | ○ | |||||||||||||||||

● means to cover the hole. ○ means to uncover the hole. ◐ means half-cover.

A modern "Baroque" recorder usually has a range of two octaves and one tone. The chart above shows "English" fingerings for this range. Most recorders made today use these fingerings, with small changes. However, recorder fingerings can vary a lot between different models. Players might use several fingerings for the same note to get the right tune. This chart is a general guide, but it's not a complete list of all possible recorder fingerings.

Recorder History

Early Recorders: The Middle Ages

The oldest known duct flutes are from the Stone Age. They are found in almost every music tradition worldwide. Recorders are special because of their thumb hole and seven finger holes. But it's sometimes hard to classify very old instruments. We don't have many records about how recorders were played in their earliest history.

How Medieval Recorders Looked

We know about medieval recorders from a few old instruments and paintings.

Old Instruments Found

The first medieval recorder found was in 1940 in the Netherlands. It was made of fruitwood and is called the "Dordrecht recorder." It's from between 1335 and 1418. It has a cylindrical shape and is about 300 mm (12 inches) long.

Another old instrument, the "Göttingen recorder," was found in Germany in 1987. It's from between 1246 and 1322. It's also made of fruitwood and is about 256 mm (10 inches) long. Its holes get smaller towards the top. A rebuilt version of this recorder has a strong, clear sound and a range of two octaves.

More medieval instruments have been found recently. Common features of these old recorders include:

- A narrow, cylindrical shape (except the Göttingen recorder).

- A double seventh hole. This allowed players to use either their right or left hand at the bottom. The hole not used was plugged with wax.

- The seventh hole produced a semitone (half step) instead of a full tone. This made playing chromatic notes (notes outside the main scale) difficult.

These early flutes are seen as ancestors to the recorders we know today.

Recorders in Art

Medieval paintings often show cylindrical recorders. The earliest pictures are probably from a church painting in Macedonia (started 1315). It shows a man playing a cylindrical recorder. Another painting from Spain (around 1390) shows angels playing cylindrical recorders.

From the Middle Ages onwards, angels were often shown playing recorders. Sometimes, three angels played recorders together. This might have shown the idea of the trinity.

Music for Medieval Recorders

No music specifically for the recorder from before 1500 has survived. But paintings from the 1400s show groups of recorder players. This means recorders were used in ensembles, sometimes with other instruments. Early music for recorders was likely vocal music.

Today, recorder players sometimes play instrumental music from that time. They might play old dances or arrange vocal works for recorder groups.

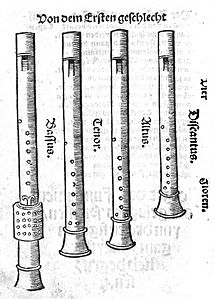

The Renaissance Recorder

In the 1500s, we have much more information about the recorder. It was one of the most important wind instruments of the Renaissance. Many recorders from this time still exist, including full sets (consorts). This period also saw the first books describing the recorder. These books were written by people like Sebastian Virdung (1511) and Silvestro Ganassi dal Fontego (1535).

How Renaissance Recorders Looked

The recorder changed a lot in the 1500s. These changes happened in different regions, and several types of recorders existed at the same time.

Old Instruments Found

Most surviving Renaissance recorders have a wide, cylindrical shape at the top. Then they narrow down towards the bottom hole, and flare out slightly at the bell. They look like a stretched hourglass. Their sound is warm and rich. Many of these recorders are tuned around A = 466 Hz. But there wasn't a standard pitch back then.

These recorders usually had a range of an octave and a minor seventh. This range was good for playing vocal music. This type is often called the "normal" Renaissance recorder.

Another type of Renaissance recorder had a narrow cylindrical shape, like medieval ones. The Rafi family, instrument makers in France in the early 1500s, made the earliest surviving recorders of this type. These Rafi recorders have a quiet sound and good pitch stability.

In 1556, French writer Philibert Jambe de Fer gave fingerings for hybrid instruments like the Rafi recorders. These fingerings allowed a range of two octaves.

Old Books About Recorders

| Recorders in sixteenth- and early seventeenth-century books | ||

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| Virdung, Musica getutscht (1511) | Agricola, Musica instrumentalis deudsch (1529) | Praetorius, Syntagma Musicum (1629) |

The first two books about recorders in the 1500s were by Sebastian Virdung (1511) and Martin Agricola (1529). These books showed recorders that looked different from the ones that survived.

Virdung's book, Musica getutscht, was the first printed book on Western musical instruments. It was written for wealthy amateur musicians. Virdung showed four recorders: a basset, two tenors, and an alto. He also gave the first fingering chart for a recorder.

Agricola's book, Musica instrumentalis Deudsch, was similar. He also showed recorders playing in four-part groups. Agricola mentioned using vibrato and different ways of articulating notes.

The next important book was Opera Intitulata Fontegara (1535) by Silvestro Ganassi dal Fontego. This was the first book focused only on playing the recorder. Ganassi was a professional musician in Venice. He taught how to play the recorder like a professional or virtuoso.

Ganassi's book has two main parts. The first is about playing technique. The second shows how to add ornaments to melodies. Ganassi stressed imitating the human voice. He believed the recorder could do this very well. He gave fingerings for a wide range of notes. He also used different syllables like "te che" and "le re" for articulation.

Gerolamo Cardano's De Musica (around 1546) also talked about recorder playing. He mentioned new techniques like partly closing the bell. He also described a vibrato effect.

Philibert Jambe de Fer (around 1515–1566) was the only French writer in the 1500s to write about the recorder. He preferred the Italian name flauto. His fingering chart was important for showing how to play higher notes.

Michael Praetorius's Syntagma musicum (1614–20) was a huge book about music and instruments. In it, he described eight sizes of recorders. Praetorius was the first to explain that recorders can sound an octave lower than they are. He also showed how different recorder consorts could be used.

"Double Recorder"

Some old paintings show musicians playing two flutes at once. Sometimes these flutes were separate. Other times, they were attached and parallel. It's not clear if these were considered a single instrument or a type of recorder.

An instrument with two attached, parallel flutes was found in Oxford. It's from the 1400s or 1500s. It has four finger holes and a thumb hole for each hand. The pipes played a fifth apart. This instrument is unique, and its classification is debated.

"Ganassi" Recorders Today

In the 1970s, recorder makers started making copies of old recorders. One famous copy is the "Ganassi" model by Fred Morgan. It was designed to play the highest notes mentioned in Ganassi's book. But these notes were not commonly used back then. So, "Ganassi recorders" today refer to this specific modern model.

Music for Renaissance Recorders

Recorders were probably first used for vocal music. Later, they played instrumental music like dances. Much vocal music from the 1400s to 1600s can be played on recorder consorts. Old books show that choosing the right recorders for vocal music was common. Some music collections were even marked as suitable for recorder consorts.

In 1533, Pierre Attaingnant published music for "nine-holed flutes" (recorders). This was the first published music specifically for a recorder consort.

King Henry VIII was a keen recorder player. When he died in 1547, his possessions included 76 recorders!

Recorders were also played with other instruments, especially in England. This was called a "mixed consort."

Other famous Renaissance composers whose music works well on recorder consorts include:

- Anthony Holborne (around 1545–1602)

- Tielman Susato (around 1510–1570)

Recorders in Culture

The recorder was very popular in the 1500s. It was one of the most common instruments of the Renaissance. Paintings show upper-class men and women playing it. Virdung's teaching book (1511) was for amateur musicians.

William Shakespeare mentioned the recorder in his play Hamlet. John Milton also mentioned "soft recorders" in Paradise Lost (1667).

Baroque Recorders

In the 1600s, recorders changed. These new instruments are called Baroque recorders. They had a "sweeter" sound but were not as loud, especially in the low notes.

The French Hotteterre family is often given credit for these changes. They made the inside of the recorder more tapered. This brought the finger-holes closer together, allowing for a wider range of notes. They also made recorders in several jointed sections. This allowed for more precise shaping and minor tuning adjustments.

The Baroque recorder sounds brightest and projects best in its second octave. This range is easier to play than on older recorders. Composers like Bach, Telemann, and Vivaldi used this feature in their concertos.

A Baroque alto recorder can play about two octaves and a fifth. But even the best instruments couldn't play some very high notes.

Music for Baroque Recorders

During the Baroque period, the recorder was linked to nature scenes, special events, and love stories. You can find recorders in literature and art from this time. Composers like Purcell, J. S. Bach, Telemann, and Vivaldi used the recorder to sound like shepherds or birds.

Even though Baroque recorders were more standardized, there's still some confusion. It's not always clear which instrument should be used for certain "flute" parts from this time.

Bach's Fourth Brandenburg Concerto

Bach's Fourth Brandenburg Concerto (BWV 1049) has parts for two "echo flutes." Later, Bach rewrote this concerto for harpsichord and two "fiauti à bec" (recorders). The recorder parts in the rewritten version were changed to fit comfortably on alto recorders.

There's a lot of debate about what "echo flutes" meant in the original concerto. Some think both parts should be played on alto recorders. Others think the first part should be on an alto in G and the second on an alto in F. Some music experts believe Bach might have intended special "echo flutes" for the second movement.

Some old instruments might be "echo flutes." One in Leipzig has two recorders with different sounds joined together.

Vivaldi's "Concertos for Flautino"

Vivaldi wrote three concertos for the flautino (little flute). These pieces are very difficult and show off the player's skill. They were possibly written for students at a music school in Venice.

The name flautino has caused debate. Some thought it meant a small transverse flute. Others suggested the "French" flageolet. Today, two instruments are usually accepted for these concertos:

- The sopranino recorder (sounds an octave higher than written).

- The soprano recorder (music is transposed down a fourth).

Most experts now believe Vivaldi probably wrote these for the sopranino recorder.

Recorders in the Classical and Romantic Eras

The recorder was not used much in classical and romantic music. People have wondered why it declined. They also debate if any duct flutes from this time are actually recorders.

Music from This Time

One known recorder piece from the late 1700s is a trio sonata by C. P. E. Bach. It's for viola, bass recorder, and continuo. This is one of the only important solo pieces for bass recorder from that time.

The recorder's last appearances in art music seem to be in works by Carl Maria von Weber in the early 1800s.

Why the Recorder Declined

Many reasons have been suggested for the recorder's decline:

- It didn't have many professional players.

- Its true sound wasn't always appreciated.

- Composers found its high range difficult to write for.

- It was hard to make and play the highest notes.

- Other instruments like the transverse flute became more popular. These flutes were made louder and had a wider range by adding keys. The recorder didn't get these same improvements.

Some researchers believe the recorder didn't disappear completely. They think it changed into other instruments, like the flageolet and the csakan.

Other Duct Flutes

Duct flutes remained popular even as the recorder faded. Some 19th-century duct flutes are considered successors to the recorder. These include the English flageolet and the csakan. They were popular with amateur musicians.

Flageolets

The word flageolet has been used since the 1500s for small duct flutes. It was first described in 1636. It had four finger holes and two thumb holes. Flageolets were popular in France and then in England. Early English recorder tutors even used flageolet music notation.

In the early 1800s, new features were added to the flageolet, like keys. They also added ways to deal with moisture inside the instrument. Around 1800, the recorder started being called the "English flageolet." This was to distinguish it from the "French flageolet."

Csakan

The csakan was a duct flute popular in Vienna from about 1800 to the 1840s. It was shaped like a walking stick or an oboe. It was played using recorder fingerings. It was usually pitched in A-flat or G.

The first csakan appeared in 1807. Some believe it came from a Hungarian war hammer that was turned into a recorder. It became fashionable to make walking sticks with hidden functions, and the csakan was the most popular.

Early csakans had no keys. But later ones could have up to thirteen keys. There were also "simple" csakans with one key and "complex" ones with many keys. The csakan was mainly for amateur musicians. But some professionals, like Ernst Krähmer, played it with great skill.

About 400 pieces were written for the csakan in the early 1800s. These were mostly for solo csakan, duets, or with guitar or piano.

The csakan is closely related to the recorder because of its fingerings and design. Some Baroque recorders were even changed around 1800 by adding keys, similar to those on csakans.

The Recorder's Modern Comeback

The idea of a recorder "revival" means it became popular again after a quiet period. Some families continued making recorders, but it wasn't as widespread.

In the early 1900s, the Bogenhauser Künstlerkapelle (Bogenhausen Artists' Band) used old recorders. But the recorder was mostly seen as a historical instrument.

The recorder's big comeback is often linked to Arnold Dolmetsch. He helped make it popular in the United Kingdom. But others in Europe also worked independently to revive it.

Famous Players

Carl Dolmetsch, Arnold's son, became one of the first great recorder players in the 1920s. He asked leading composers to write new music for the recorder. This, along with a Dutch school of recorder playing, helped the recorder become a serious solo instrument.

Important players who helped the recorder's comeback include Frans Brüggen and David Munrow. Brüggen recorded many historical pieces and asked for new works. Munrow's 1975 album The Art of the Recorder is an important collection of recorder music.

Today, many talented soloists and groups play the recorder. They perform both old and new music.

How Modern Recorders Are Made

Early modern recorders were copies of old instruments. Arnold Dolmetsch started making his own recorders after losing his antique ones. Early 20th-century recorders looked like Baroque models but were different inside. Dolmetsch introduced "English fingering," which is now standard. He also standardized the double 6th and 7th holes.

In Germany, Peter Harlan started making recorders in the 1920s for schools. These recorders were different from old ones. They had wide windways and changed fingering systems.

In the late 1900s, players wanted to perform music as it sounded long ago. So, recorder makers like Friedrich von Huene started researching old recorders. They aimed to make instruments that sounded like the antiques.

Today, almost all recorders are based on old models. Many makers can trace their skills back to these pioneers. Some modern makers even create electroacoustic recorders or add keys to extend the range to over three octaves.

Modern Recorder Music

Almost twice as many pieces have been written for the recorder since its modern comeback than in all its previous history. Many of these are by modern composers who use the recorder's unique sounds and playing techniques.

Famous modern composers who wrote for the recorder include Paul Hindemith, Luciano Berio, and Benjamin Britten.

The recorder is also used in popular music. It's a teaching instrument and easy to make sound. Bands like The Beatles, the Rolling Stones ("Ruby Tuesday"), and Led Zeppelin ("Stairway to Heaven") have used it.

Recorders in Schools

In the 1900s, Carl Orff used the recorder in his teaching method, Orff-Schulwerk. His music books for children included pieces for recorders.

Recorders are now often made from plastic. This makes them cheap to produce and buy in large numbers. Because of this, they are very popular in schools. They are also relatively easy to play at a basic level. You just need to blow, and your fingers mostly control the pitch.

Recorder Groups

The recorder is a very social instrument. Many recorder players join large groups or smaller chamber groups. There's a lot of music for these groups, including many modern pieces. Using different sized recorders together helps make up for the limited range of a single instrument.

Common groups include four-part arrangements with soprano, alto, tenor, and bass recorders. More complex groups with many parts for each instrument, and even lower or higher instruments, are also common.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Flauta dulce para niños

In Spanish: Flauta dulce para niños

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |