Tin whistle facts for kids

Several high D tin whistles

from left to right: Clarke Sweetone; Shaw (customised); O'Brien; Reyburn; Generation (customised); Copeland; Overton |

|

| Woodwind instrument | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Penny whistle |

| Classification |

|

| Hornbostel–Sachs classification | 421.221.12 (Open flute with internal duct and fingerholes) |

| Playing range | |

| Two octaves | |

| Related instruments | |

The tin whistle, also known as the penny whistle, is a simple six-holed woodwind instrument. It is a type of fipple flute. This means you blow air into a special mouthpiece called a "fipple." Other instruments like the recorder are also fipple flutes. A tin whistle player is called a whistler. The tin whistle is very popular in Irish traditional music and Celtic music. Other names for this instrument include the flageolet, English flageolet, Scottish penny whistle, tin flageolet, or Irish whistle (also Irish: feadóg stáin or feadóg).

Contents

The Tin Whistle's Journey Through Time

The tin whistle we know today comes from a big family of fipple flutes. These instruments have been played in many different forms and cultures around the world for a very long time. In Europe, they have a rich history. Famous types include the recorder, tin whistle, Flabiol, Txistu, and tabor pipe.

How Did the Tin Whistle Start?

Almost every early culture had some kind of fipple flute. It was probably the first flute-like instrument that could play different notes. For example, scientists found a possible Neanderthal fipple flute in Slovenia. It might be as old as 81,000 to 53,000 BC! A German flute from 35,000 years ago also exists.

Ancient writings describe fipple-type flutes like the Roman tibia and Greek aulos. By the 12th century, Italian flutes came in many sizes. Pieces of 12th-century Norman bone whistles have been found in Ireland. A complete 14th-century clay whistle was found in Scotland.

In the 17th century, whistles were called flageolets. This term described a whistle with a French-made fipple mouthpiece. This is similar to the modern penny whistle. Some modern tin whistlers still prefer the name flageolet. They feel it better describes this wide group of fipple flutes.

The Tin Whistle in the 1800s

The modern penny whistle comes from Great Britain and Ireland. Robert Clarke started making "tin whistles" in factories in England from 1840 to 1889. His company also sold them as "Clarke London Flageolets."

The way you play the tin whistle (its fingering) is like the six-hole simple system Irish flutes. This six-hole system was well-known before Robert Clarke started making his whistles. Clarke's first whistle, the Meg, played in a high A note. Later, he made them in other keys for popular Victorian music. His company even showed the whistles at The Great Exhibition in 1851.

Clarke tin whistles often sound like organ pipes. They have a flattened tube that forms the mouthpiece. They were made from rolled tin or brass. These whistles were made in large numbers and were very popular because they were cheap.

People used to think the "penny whistle" was called that because children or street musicians were paid a penny to play it. But actually, it was called that because you could buy one for just a penny! The name "tin-whistle" was first used around 1825. However, neither "tin whistle" nor "penny whistle" became common until the 20th century. The instrument became popular in English, Scottish, Irish, and American traditional music.

Because they were so affordable, tin whistles were common in many homes. They were as popular as the harmonica. Some flute makers also sold whistles in the late 1800s. These often had cylindrical brass tubes. Many old whistles had lead parts in their mouthpieces. Since lead is poisonous, you should be careful if you find an old whistle.

What is a Low Whistle?

Most whistles are high-pitched. However, "low" whistles have also been made for a long time. The Museum of Fine Arts in Boston has a low whistle from the 1800s in its collection.

Modern Tin Whistles Today

Today, most whistles are made of brass or nickel-plated brass. They have a plastic mouthpiece that contains the fipple. Brands like Generation, Feadóg, Oak, Acorn, and Walton's make these types of whistles.

The Generation Whistle came out in 1966. It had a brass tube and a lead fipple. Alfred Brown started the company in England. Their most popular whistle, the Generation Flageolet, was introduced in 1968. Over time, the design changed. The most important change was replacing the lead fipple with a plastic one.

Most whistles have a straight, tube-like shape inside (a cylindrical bore). But other designs exist. For example, Clarke's brand makes a conical (cone-shaped) metal whistle. It has a wooden plug at the wide end to form the fipple. Other less common types include all-metal whistles, PVC whistles, and wooden whistles.

The tin whistle became very popular as a folk instrument in the early 1800s. It is now a key part of many folk traditions. Whistles are a great starting instrument for English, Scottish, and Irish traditional music. They are usually cheap and easy to play. They don't require tricky mouth positions like the transverse flute. Also, their fingerings are almost the same as traditional six-holed flutes, like the Irish flute and the Baroque flute. The tin whistle is also a good way to learn the uilleann pipes. It has similar finger techniques and notes. Today, the tin whistle is the most popular instrument in Irish traditional music.

In recent years, some instrument makers have started making "high-end" handmade whistles. These can cost hundreds of US dollars. While expensive compared to cheap whistles, they are still cheaper than most other instruments. These companies are usually just one person or a small group of skilled craftspeople. Each whistle is made and "voiced" (tuned and adjusted) by hand, not in a factory.

How Tin Whistles Are Tuned

Understanding Whistle Keys

A whistle is tuned diatonically. This means it's designed to easily play music in two main keys. These keys are a perfect fourth apart. It can also play the natural minor key and Dorian mode a major second above its lowest note.

A whistle is named by its lowest note. This note is the tonic of the lower of its two main major keys. This way of naming the instrument's key is different from how chromatic instruments are named.

Whistles are made in all 12 chromatic keys. However, the most common whistles are in D. After D, C and F are common, then G, B♭, and E♭. Other keys are rarer. A D whistle can easily play notes in the keys of D and G major. Since D major is lower, these are called D whistles. The next most common is a C whistle, which plays notes in C and F major. The D whistle is by far the most popular for Irish and Scottish music.

The whistle is mainly a diatonic instrument. But you can play notes outside its main key. You can do this by half-holing (partially covering a finger hole) or by cross-fingering (covering some holes while leaving higher ones open). Half-holing can be tricky. Since whistles are available in all keys, players usually just use a different whistle for other keys. They save half-holing for accidentals (notes outside the main scale). Some whistles let you use one mouthpiece with different keyed bodies.

What is a Low Whistle?

During the 1960s, traditional Irish music became popular again. At this time, the low whistle was "recreated" by Bernard Overton for musician Finbar Furey.

These are larger whistles. Because they are longer and wider, they make notes an octave (or sometimes two octaves) lower. Low whistles are usually made of metal or plastic tubing. They often have a tuning-slide head. They are almost always called low whistles or sometimes concert whistles. The low whistle works just like standard whistles. However, musicians often see it as a separate instrument.

The term soprano whistle is sometimes used for higher-pitched whistles. This helps tell them apart from low whistles.

How to Play the Tin Whistle

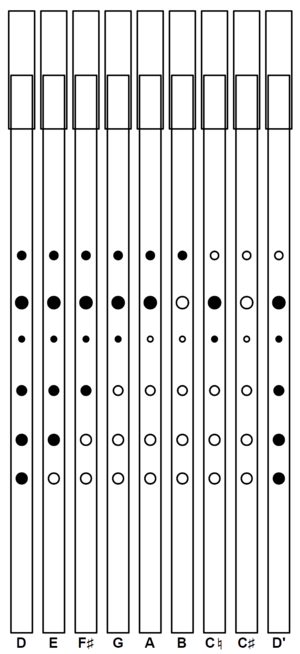

Fingering and How Many Notes It Can Play

You choose notes by opening or closing holes with your fingers. You usually cover the holes with the soft pads of your fingers. Some players, especially on larger low whistles, might use the "piper's grip." When all holes are closed, the whistle plays its lowest note. This is called the whistle’s “bell tone.”

To play other notes, you open holes from the bottom up. For example, opening the lowest hole plays the second note. Opening the lowest two holes plays the third, and so on. With all six holes open, it plays the seventh note.

Like many woodwind instruments, the tin whistle plays higher notes by blowing air faster into the mouthpiece. On a flute, you change your mouth shape. But on a tin whistle, the air path is fixed. So, you just blow harder. This is called overblowing.

The fingerings for higher notes are usually the same as for lower notes. However, sometimes different fingerings are used for the very highest notes. This helps keep them in tune. Also, the lowest note of the higher octave is usually played with the top hole partly open. This makes it harder to accidentally drop to the lower octave and helps with tuning.

You can also play other notes (sharper or flatter than the main scale) using cross fingering. This means covering some holes while leaving higher ones open. You can also flatten notes by half holing (partially covering a hole). The most useful cross fingering makes the seventh note flatter. For example, on a C whistle, it plays B♭ instead of B. This lets you play another major scale (like F on a C whistle).

A standard whistle can play two octaves. For a D whistle, this means notes from D5 to D7. That's from the second D above middle C to the fourth D above middle C. You can make sounds even higher by blowing very hard. But usually, these sounds are too loud and out of tune.

Adding Style to Your Music

Traditional whistle playing uses special ways to decorate the music. These are called ornaments. They include cuts, strikes, and rolls. Most playing is smooth (legato), with ornaments used to create breaks between notes. This is different from using your tongue to separate notes. In traditional music, "ornamentation" means changing how a note is played, rather than adding new notes. Common ornaments include:

- Cuts

- A cut is when you briefly lift a finger above the note you are playing. You do this without stopping the air flow into the whistle. For example, if you are playing a low D on a D whistle, you can "cut" the note. You just briefly lift the first finger of your lower hand. This makes the pitch briefly go up. You can do a cut at the very start of a note or after it has already started. Some call the latter a "double cut" or a "mid-note cut."

Playing Tips and Tricks

- Leading tone

- A leading tone is the seventh note right before the main note (the tonic). It's called this because melodies often use the seventh note to lead into the tonic at the end of a musical phrase. On most tin whistles, you can play the leading tone to the lowest tonic. You do this by using the little finger of your lower hand to partly cover the very end opening of the whistle. All other holes stay covered, just like for the tonic.

- Tone

- The sound (tone) of a tin whistle mostly depends on how it's made. Clarke-style metal whistles often have an airy, "impure" sound. Generation-style cylindrical whistles usually have clear, "pure" sounds. Some cheap metal whistles can sound very airy. They might also be hard to play in the upper notes (second octave). You can often improve the sound and playability. Try putting a small piece of tape over one edge of the fipple slot (just below the mouthpiece). This makes the opening narrower. Another way to improve the sound on some plastic mouthpieces is to add a small piece of poster-putty on the inside. This makes the air block longer and keeps the air stream narrow before it hits the fipple's edge.

- Scales

- As mentioned earlier, a player usually plays a whistle in its main key and the key starting on the fourth note (like G on a D whistle). However, you can play in almost any key. It gets harder to stay in tune as you move further away from the whistle's main key. This follows the circle of fifths. So, a D whistle is good for playing in G and A. A C whistle can be used fairly easily for F and G.

Images for kids

-

Fingering for the diatonic scale on a D tin whistle: I, II, III, IV, V, VI, ♭VII, ♮VII, I'

See also

In Spanish: Flauta irlandesa para niños

In Spanish: Flauta irlandesa para niños

| James B. Knighten |

| Azellia White |

| Willa Brown |