Michael Praetorius facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Michael Praetorius

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 28 September 1571 (most likely) Creuzburg

|

| Died | 15 February 1621 (aged 49) Wolfenbüttel

|

| Occupation |

|

Michael Praetorius (born around September 28, 1571 – died February 15, 1621) was a German composer, organist, and music theorist. He was one of the most skilled musicians of his time. He was very important for creating new musical styles based on Protestant church songs, called hymns.

Contents

Life of a Musician: Michael Praetorius

Praetorius was born Michael Schultze. He was the youngest son of a Lutheran pastor. He was born in Creuzburg, which is now in Thuringia, Germany. He went to school in Torgau and Zerbst. Later, he studied religion and philosophy at the University of Frankfurt (Oder). He could speak several languages.

After his music training, he became an organist in 1587. He worked at the Marienkirche in Frankfurt. From 1592 or 1593, he worked for Duke Henry Julius in Wolfenbüttel. He started as an organist in the duke's orchestra. By 1604, he became the Kapellmeister, which means the court music director.

Early Compositions and New Styles

Praetorius's first musical pieces were published around 1602 or 1603. These works showed how much the court in Gröningen cared about music. His motets from this time were the first in Germany to use new Italian music styles. This made him known as a very skilled composer.

These "modern" pieces marked the end of his middle period of creating music. He then published nine parts of his Musae Sioniae (1605–1610). He also released collections of church music in 1611. These included masses, hymns, and magnificats. These works followed the German Protestant chorale style. He wrote them for Duchess Elizabeth, who was in charge while the duke was away.

Working in Dresden and Wolfenbüttel

When Duke Henry Julius died in 1613, Praetorius kept his job in Wolfenbüttel. But he also started working for John George I in Dresden. He was a "nonresident music director" there. His job was to create music for special events and celebrations.

In Dresden, he learned about the newest Italian music. This included the polychoral music from the Venetian School. This style used several choirs singing in different places. This helped him develop the chorale concerto style, especially with multiple choirs. He was inspired by composers like Giovanni Gabrieli.

The music Praetorius wrote for these events showed his greatest artistic skill. People like Gottfried Staffel and Matthias Hoë von Hoënegg wrote about how famous Praetorius was. They described how his music impressed important people, including Emperor Matthias. In Dresden, Praetorius also worked with Heinrich Schütz from 1615 to 1619.

Later Life and Death

It seems Praetorius's job in Wolfenbüttel ended around 1620. He was likely already sick by then. He died in Wolfenbüttel on February 15, 1621, at 49 years old. He was buried in a vault under the organ of the Marienkirche, Wolfenbüttel on February 23.

What's in a Name?

Praetorius's family name in German was spelled in many ways. These included Schultze, Schulte, Schultheiss, Schulz, and Schulteis. The name Praetorius was the common Latin version of this family name. Schultze in German means "village judge" or "magistrate." The Latin word Praetorius means "related to a magistrate" or "someone with the rank of a magistrate."

Musical Works

Praetorius wrote a lot of music. His compositions show the influence of Italian composers and his younger friend, Heinrich Schütz. He published 17 volumes of music between 1605 and 1613. This was during his time as music director for Duke Heinrich Julius.

His nine-part Musae Sioniae (1605–1610) was a collection of chorales and German church music. It was written for 2 to 16 voices. He also published a large collection of Latin church music called Liturgodiae Sioniae.

His most famous work today is Terpsichore. This is a collection of over 300 instrumental dances. It is his only surviving non-religious work from a planned larger collection.

Many of Praetorius's choir pieces were written for several smaller choirs. These choirs would be placed in different parts of the church. This was like the Venetian polychoral music of Gabrieli.

Praetorius also wrote the well-known musical arrangement for the Christmas carol Es ist ein Ros entsprungen (Lo, How a Rose E'er Blooming) in 1609.

Published Music Collections

- Musae Sioniae I (Lutheran chorales, 8 voices, 1605)

- Motectae et Psalmi Latini (Latin motets and psalms, 8 voices, 1607)

- Musae Sioniae II (Lutheran chorales, 8 voices, 1607)

- Musae Sioniae III (Lutheran chorales, 8–12 voices, 1607)

- Musae Sioniae IV (Lutheran chorales, 8 voices, 1607)

- Musae Sioniae V (Lutheran chorales, 2–8 voices, 1607)

- Musae Sioniae VI (Lutheran chorales for church festivals, 4 voices, 1609)

- Musae Sioniae VII (Lutheran chorales for everyday use, 4 voices, 1609)

- Musae Sioniae VIII (Lutheran chorales for Christian life, 4 voices, 1609)

- Musae Sioniae IX (Lutheran chorales for church or home, 2–4 voices, 1610)

- Missodia Sionia (Latin mass settings, 1611)

- Hymnodia Sionia (Latin hymn settings, 2–8 voices, 1611)

- Eulogodia Sionia (Latin settings, 2–8 voices, 1611)

- Megalynodia Sionia (Magnificat settings, Latin, 1611)

- Terpsichore (Courtly dances, 1612)

- Urania (chorales for congregation and up to 4 choirs, 1613)

- Polyhymnia caduceatrix (Lutheran chorales in the new Italian style, 1619)

- Polyhymnia exercitatrix (Latin Halelujah settings and Lutheran chorales in Italian style, 1620)

- Puericinium (settings for children, 1621)

Organ Music

- Christ, unser Herr, zum Jordan kam – Fantasia (Musæ Sioniæ VII, 1609)

- Ein’ feste Burg ist unser Gott – Fantasia (Musæ Sioniæ VII, 1609)

- Wir glauben all an einen Gott – Fantasia (Musæ Sioniæ VII, 1609)

- Nun lob, mein Seel, den Herren – 2 Variations (Musæ Sioniæ VII, 1609)

- Alvus tumescit virginis – Advent-Hymn « Veni redemptor gentium » (Hymnodia Sionia, 1611)

- A solis ortus cardine – Christmas-Hymn (Hymnodia Sionia, 1611)

- Summo Parenti gloria – (v8. A solis ortus cardine) (Hymnodia Sionia, 1611)

- Vita sanctorum – Easter-Hymn (Hymnodia Sionia, 1611)

- O lux beata Trinitas – Trinity-Hymn (Hymnodia Sionia, 1611)

- Te mane laudum carmine – (v2. O lux beata Trinitas) (Hymnodia Sionia, 1611)

Musical Writings and Teachings

Praetorius was also a music scholar. His writings were well-known to other musicians in the 1600s. He didn't create many new theories himself. Instead, he wrote down everything about how music was played and understood at the time.

He helped improve figured bass (a way of writing music) and musical tuning. But his most important contribution was explaining how instruments and voices were used together. He also wrote about the standard musical pitch and the state of modes, meter, and fugal theory. His detailed records of 17th-century music practices were very helpful for musicians in the 1900s who wanted to play old music.

His large but unfinished book, Syntagma Musicum, came out in three volumes between 1614 and 1620.

- The first volume (1614), Musicae Artis Analecta, was mostly in Latin. It discussed ancient music and church music.

- The second volume, De Organographia (1618), was about musical instruments, especially the organ. It was one of the first music theory books written in German.

- The third volume, Termini Musicali (1618), also in German, explained different types of compositions and important skills for professional musicians.

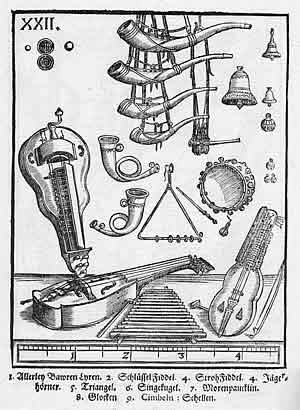

- An extra part for the second volume, Theatrum Instrumentorum seu Sciagraphia (1620), had 42 woodcut pictures. These showed instruments from the early 1600s, grouped by type and shown to scale.

Praetorius had planned a fourth volume about composing music, but he died before finishing it. Gustave Reese, a music historian, said that Syntagma Musicum was one of the most important sources for learning about 17th-century music history.

Praetorius wrote in a detailed style, with many side notes and puzzles. This was common for scholars in the 1600s. He was a lifelong Christian and often wished he had become a priest. He wrote several religious books, but they are now lost. As a strong Lutheran, he helped a lot with developing church services in German. But he also liked Italian ways of composing and playing music.

See also

In Spanish: Michael Praetorius para niños

In Spanish: Michael Praetorius para niños

| Aaron Henry |

| T. R. M. Howard |

| Jesse Jackson |