European nightjar facts for kids

Quick facts for kids European nightjar |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Caprimulgiformes |

| Family: | Caprimulgidae |

| Genus: | Caprimulgus |

| Species: |

C. europaeus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Caprimulgus europaeus Linnaeus, 1758

|

|

|

|

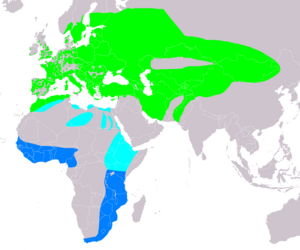

| Range of C. europaeus Breeding Passage Non-breeding | |

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

| Synonyms | |

|

C. centralasicus |

|

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

The European nightjar (Caprimulgus europaeus) is a special bird that is active at dawn and dusk and during the night. It's also known as the common goatsucker or just nightjar. These birds breed across most of Europe and Asia, reaching as far as Mongolia and China.

The name Caprimulgus comes from an old story. People used to believe that nightjars would suck milk from goats at night, making the goats stop giving milk. This is just a myth, though!

Nightjars have amazing camouflage. Their grey and brown feathers help them blend in perfectly with trees and the ground. This makes them very hard to spot during the day when they are resting. Male nightjars have white patches on their wings and tail that you can see when they fly at night.

These birds love dry, open areas with some trees and bushes. You might find them in heaths, forest clearings, or newly planted woods.

About the European Nightjar

What is a Nightjar?

Nightjars belong to a large family of birds called Caprimulgidae. Most nightjars are active at night and eat insects. The European nightjar is part of the Caprimulgus group. These birds have stiff bristles around their mouths, long pointed wings, and a special comb-like claw on their middle toe.

The name "nightjar" was first used in 1630. It describes how the bird is active at night and the "jar" part comes from its unique churring song. Some old names for this bird include "fern owl" because of where it lives, and "moth hawk" because of what it eats.

Different Types of European Nightjars

There are six different types, or subspecies, of the European nightjar. They look a bit different depending on where they live. Birds in the east tend to be smaller and paler. Males in the east also have bigger white spots on their wings. These small differences show how animals can change over time to fit their environment.

Appearance of the European Nightjar

The European nightjar is about 24.5 to 28 centimeters (9.6 to 11 inches) long. Its wings can spread out to 52 to 59 cm (20 to 23 in). Males usually weigh between 51 and 101 grams (1.8 to 3.6 ounces), and females weigh 67 to 95 grams (2.4 to 3.4 ounces).

Their feathers are mostly greyish-brown with dark stripes. They have a pale buff (light yellowish-brown) collar on the back of their neck and a white line near their mouth. Their wings are grey with buff spots, and their belly is greyish-brown with brown stripes.

Flight and Feathers

Nightjars fly very quietly because their feathers are soft. They have long, pointed wings that help them glide. You can tell a male from a female when they fly. Males have a white patch on three of their main wing feathers and white tips on their two outer tail feathers. Females do not have these white markings.

Young nightjars are covered in soft brown and buff feathers. As they grow, they start to look like the adult females. Adult birds change their body feathers after breeding. They finish changing their tail and flight feathers during winter in Africa.

How to Spot a Nightjar

Because nightjars are active at night and blend in so well, it can be tricky to see them. They are often confused with other nightjar species. For example, the red-necked nightjar, which lives in Spain and North Africa, is larger and greyer. It also has a wider buff collar. Finding a nightjar often takes a bit of luck!

The Nightjar's Voice

The male European nightjar has a very special song. It's a long, continuous "churring" sound that can last for up to 10 minutes! He sings from a perch, often moving to different spots in his area. He sings most often at dawn and dusk.

It can be hard to find a singing male nightjar. They are difficult to see in low light, and their song can sound like it's coming from different directions as the bird turns its head. The song can be heard from 200 meters (650 feet) away, and even up to 600 meters (2,000 feet) in quiet conditions. Sometimes, it can be mistaken for the sound of a European mole cricket.

Female nightjars do not sing. Both males and females make a short "cuick, cuick" call when they are flying or chasing away predators. They also make a sharp "chuck" sound if they are worried. Young nightjars will hiss loudly and open their mouths wide if they feel threatened.

When you hear a "wing-clap" sound, it's not the bird clapping its wingtips together. It's actually made when each wing snaps downwards very quickly, like a whip.

Where European Nightjars Live

European nightjars breed across Europe, up to about 64°N latitude, and across Asia, up to about 60°N, reaching as far east as Mongolia. Their southern breeding areas include parts of North Africa, Iraq, Iran, and the Himalayas.

Migration Journey

All European nightjars migrate, meaning they travel long distances for winter. Most of them spend winter in Africa, south of the Sahara Desert. They usually migrate at night, either alone or in small groups. Birds from Europe fly across the Mediterranean Sea and North Africa. Birds from Asia travel through the Middle East and East Africa. Some Asian birds can travel across 100 degrees of longitude! Many birds start their migration around the time of a full moon.

They usually leave their breeding grounds in August or September and return by May. Recent studies show that European nightjars make a loop migration. They cross big natural barriers like the Mediterranean Sea, the Sahara Desert, and the Central African Tropical Rainforest.

Preferred Habitats

The European nightjar likes dry, open areas with some trees and small bushes. This includes heaths, moorland, forest clearings, or areas where trees have been cut down and new ones are being planted. They avoid places with no trees, very dense forests, cities, mountains, and farmlands for breeding. However, they often hunt for food over wetlands, farms, or gardens.

In winter, they use a wider variety of open habitats, such as dry grasslands with acacia trees, sandy areas, and highlands. They have been seen at high altitudes, up to 2,800 meters (9,200 feet) where they breed, and 5,000 meters (16,000 feet) in their wintering areas.

Nightjar Behaviour

European nightjars are active at dusk, dawn, and night. During the day, they rest on the ground, often in a shady spot. They might also perch motionless along a tree branch, blending in perfectly. Their camouflage makes them very hard to see during the day. If they are on the ground and not in shade, they will turn to face the sun to make their shadow as small as possible.

If a nightjar feels threatened, it will flatten itself to the ground with its eyes almost closed. It will only fly away if an intruder gets very close, about 2 to 5 meters (6 to 16 feet) away. When it flies, it might make a call or wing-clap. It will then land about 40 meters (130 feet) away from where it was disturbed. In their winter homes, they often rest on the ground but also use tree branches up to 20 meters (65 feet) high. They often use the same resting spots for weeks if they are not disturbed.

Like other nightjars, they sometimes sit on roads or paths at night. They might hover to check out large animals or people. Other birds might bother them during the day, and bats or owls might bother them at night. Nightjars will mob (attack) owls and other predators like red foxes.

Nightjars also take quick dips into water while flying to wash themselves, just like swifts and swallows. They have a unique comb-like structure on their middle claw. They use this to clean their feathers and maybe to remove parasites.

In very cold weather, some nightjar species can slow down their body processes and go into a deep sleep-like state called torpor. This helps them save energy. European nightjars have been seen doing this for at least eight days without harm, but we don't know how often this happens in the wild.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

European nightjars usually breed from late May to August. Males arrive about two weeks before the females to set up their territories. They fly around with their wings in a V-shape and their tail fanned out, chasing away other birds. They might even fight in the air or on the ground.

The male's special flight display involves following the female in a rising spiral, often clapping his wings. If she lands, he continues to display by bobbing and fluttering until she spreads her wings and tail. Mating usually happens on the ground, but sometimes on a raised branch.

Eggs and Chicks

European nightjars do not build a nest. Instead, they lay their eggs directly on the ground among plants or tree roots, or under a bush or tree. They might use the same spot for several years. The ground can be bare, covered in leaves, or pine needles.

They usually lay one or two whitish eggs. These eggs are often spotted with browns and greys. Each egg is about 32 by 22 millimeters (1.3 by 0.87 inches) and weighs about 8.4 grams (0.3 ounces).

Studies show that nightjars are more likely to lay eggs in the two weeks before a full moon. This might be because it's easier to find insect food when the moon is brighter. This also helps them raise a second group of chicks in July, as that time would also have a bright moon.

The eggs hatch after about 17 to 21 days. The female does most of the sitting on the eggs, but the male might help for short periods, especially around dawn or dusk. If the female is disturbed, she might pretend to be injured to lead the intruder away. She can even move the eggs a short distance with her beak.

The chicks are born with soft downy feathers and can move around soon after hatching. They are kept warm by their parents. They learn to fly in 16 to 17 days and become independent around 32 days after hatching. If a pair nests early, they might have a second group of chicks. In this case, the female leaves the first group a few days before they can fly, and the male takes care of them while helping with the second group. Both parents feed the young with balls of insects.

Nightjars usually start breeding when they are one year old. They typically live for about four years, but some have been known to live for over 12 years in the wild.

What Nightjars Eat

The European nightjar eats many different kinds of flying insects. This includes moths, beetles, mantises, dragonflies, cockroaches, and flies. They will also pick up glowworms from plants. They eat small pieces of grit to help them digest their food.

Nightjars hunt over open areas and at the edges of woodlands. They might be drawn to insects that gather around artificial lights, near farm animals, or over still ponds. They usually hunt at night, but sometimes on cloudy days. They catch insects while flying with a light, twisting flight, or they might fly out from a perch to catch them. They drink water by dipping down to the surface while flying.

Night Vision and Hunting

European nightjars hunt by sight. They see their prey as dark shapes against the night sky. On moonlit nights, they often hunt from a perch. On darker nights, when it's harder to see, they fly continuously to find food. Studies show that they hunt much more on moonlit nights.

Even though they have small beaks, their mouths can open very wide to catch insects. They have long, sensitive bristles around their mouths. These bristles might help them find insects or guide them into their mouths. They spit out parts of insects they can't digest, like the hard outer shells, in small pellets. They often hunt near herds of animals like goats, sheep, and cattle, because these animals attract many insects.

Nightjars have relatively large eyes with a special reflective layer behind the retina. This layer makes their eyes shine in torchlight and helps them see better in low light, like at dusk, dawn, and in moonlight. Their eyes are designed for night vision, with many cells that detect light (rod cells) and fewer cells that see color (cone cells). This means they see well in the dark but not many colors. Their night vision is probably as good as an owl's. Even though they have good hearing, nightjars don't seem to use sound to find insects, and they don't use echolocation like bats do.

Who Hunts the Nightjar?

The eggs and chicks of nightjars are laid on the ground, so they can be easily found by predators. These include red foxes, pine martens, European hedgehogs, least weasels, and domestic dogs. Birds like crows, Eurasian magpies, Eurasian jays, and owls also prey on them. Snakes, such as common adders, might also steal eggs from the nest.

Adult nightjars can be caught by birds of prey like northern goshawks, hen harriers, Eurasian sparrowhawks, common buzzards, and peregrines.

Nightjars can also have parasites. These include a type of biting louse found on their wings and a feather mite that lives only on their white wing markings. They can also get bird malaria.

Status and Conservation

In 2020, there were an estimated 3 to 6 million European nightjars worldwide. In Europe, there were between 290,000 and 830,000 birds. Even though their numbers seem to be decreasing, it's not happening fast enough for them to be considered endangered. Because there are so many of them and they live in such a large area, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) classifies them as a species of least concern. This means they are not currently at risk of extinction.

The largest populations in 2012 were in Russia, Spain, and Belarus. However, their numbers have been falling in many areas, especially in northwestern Europe. This is mainly due to:

- Loss of insect prey: Fewer insects because of pesticide use.

- Disturbance: People bothering them, especially ground-nesting birds.

- Collisions: Birds hitting vehicles.

- Habitat loss: Their natural homes being destroyed.

Since they nest on the ground, nightjars are very sensitive to disturbance, especially from domestic dogs. Dogs can destroy nests or alert other predators like crows or mammals to the nest's location. Nests are more successful in areas where people don't have access. In places where people can go, successful nests are usually far from paths or homes.

In some areas, like Britain, new forests planted for commercial use have created temporary habitats for nightjars, which has helped their numbers. However, these gains might not last as the forests grow and become unsuitable for nightjars. In Ireland, the European nightjar was almost extinct in 2012.

Nightjars in Culture

Poets sometimes write about the nightjar to describe warm summer nights. For example, in "Love in the Valley" by George Meredith:

Lone on the fir-branch, his rattle-notes unvaried

Brooding o'er the gloom, spins the brown eve-jar

The name Caprimulgus and the old name "goatsucker" both come from an ancient myth. Even in the time of Aristotle, people believed that nightjars sucked milk from nanny goats. They thought this made the goats stop giving milk or even go blind. This old belief is found in nightjar names in other European languages too, like German Ziegenmelker and Italian succiacapre, which also mean goatsucker.

This myth probably started because nightjars are attracted to insects that gather around farm animals. Since nightjars are unusual birds active at night, people blamed them for any problems that happened to their livestock. Another old name, "puckeridge," was used for both the bird and a disease in farm animals. The disease was actually caused by botfly larvae under the skin. "Lich fowl" (corpse bird) is another old name that shows the superstitions people had about this strange nocturnal bird.

| Chris Smalls |

| Fred Hampton |

| Ralph Abernathy |