Hebrides facts for kids

The Inner Hebrides and Outer Hebrides |

|

| OS grid reference | NF 96507 00992 |

|---|---|

| Physical geography | |

| Island group | Hebrides |

| Administration | |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Country | Scotland |

The Hebrides (pronounced HEB-rid-eez) are a group of islands off the west coast of Scotland. These islands are split into two main parts: the Inner Hebrides and the Outer Hebrides. They are separated by a stretch of water called the Minch and the Sea of the Hebrides.

People have lived on these islands for a very long time, since the Mesolithic period. The culture of the islanders has been shaped by different groups. These include people who spoke Celtic, Norse, and English. This mix of cultures is why the islands have names from different languages.

The Hebrides are famous for being the home of much Scottish Gaelic literature and Gaelic music. Today, the island economy relies on crofting (small-scale farming), fishing, tourism, oil, and renewable energy. The Hebrides have fewer types of plants and animals than mainland Scotland. But they are home to many seals and seabirds.

Together, the islands cover about 7,285 square kilometers (2,813 square miles). In 2011, about 45,000 people lived there.

Contents

Amazing Geography and Climate

The Hebrides have a very varied geology. This means their rocks are of many different ages. Some rocks are among the oldest in Europe. They date back to the Precambrian era. Others are younger, formed by volcanic activity.

The Hebrides are divided into two main groups. The Inner Hebrides are closer to mainland Scotland. They include islands like Islay, Jura, Skye, Mull, Raasay, Staffa, and the Small Isles. There are 36 islands in this group where people live.

The Outer Hebrides are a chain of over 100 islands and small rocks. They are about 70 kilometers (43 miles) west of mainland Scotland. Fifteen of these islands are inhabited. The main ones include Lewis and Harris, North Uist, Benbecula, South Uist, and Barra.

Sometimes, the Outer Hebrides are called the Long Isle (Scottish Gaelic: An t-Eilean Fada). Today, they are also known as the Western Isles. This name can also refer to all the Hebrides.

The Hebrides have a cool, mild climate. This is surprising for how far north they are. The Gulf Stream ocean current keeps them warm. In the Outer Hebrides, the average temperature is 6°C (44°F) in January. It reaches 14°C (57°F) in the summer. Lewis gets about 1,100 millimeters (43 inches) of rain each year. It also has about 1,100 to 1,200 hours of sunshine. Summer days are long, and May to August is the driest time.

Where Do the Names Come From?

The earliest writings about the islands are from around 77 AD. Pliny the Elder called them Hebudes. Later, Ptolemy called them Ebudes. The name Ebudes might be older than the Celtic languages.

The names of many individual islands show their mixed history. Most names are from Norse or Gaelic languages. But some island names might be even older, from before Celtic times. For example, Adomnán, an abbot from Iona in the 7th century, recorded Colonsay as Colosus and Tiree as Ethica. These might be pre-Celtic names. The name of Skye is also very old and complex. Lewis is called Ljoðhús in Old Norse.

The first full list of Hebridean island names was made by Donald Monro in 1549. This list also gives the first written mention of some island names.

Outer Hebrides Names

Lewis and Harris is the biggest island in Scotland. It is the third largest in the British Isles. It includes Lewis in the north and Harris in the south. These are often called separate islands, but they are connected by land. The island doesn't have one common name. So it's often called "Lewis and Harris."

| Island | Derivation | Language | Meaning | Munro (1549) | Modern Gaelic name | Alternative Derivations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baleshare | Am Baile Sear | Gaelic | east town | Baile Sear | ||

| Barra | Barrey | Gaelic + Norse | Finbar's island | Barray | Barraigh | Old Gaelic barr, a summit. |

| Benbecula | Peighinn nam Fadhla | Gaelic | pennyland of the fords | Beinn nam Fadhla | "little mountain of the ford" or "herdsman's mountain" | |

| Berneray | Bjarnarey | Norse | Bjorn's island | Beàrnaraigh | bear island | |

| Eriskay | Uruisg + ey | Gaelic + Norse | goblin or water nymph island | Eriskeray | Èirisgeigh | Erik's island |

| Flodaigh | Norse | float island | Flodaigh | |||

| Fraoch-eilean | Gaelic | heather island | Fraoch-eilean | |||

| Great Bernera | Bjarnarey | Norse | Bjorn's island | Berneray-Moir | Beàrnaraigh Mòr | bear island |

| Grimsay | Grímsey | Norse | Grim's island | Griomasaigh | ||

| Grimsay | Grímsey | Norse | Grim's island | Griomasaigh | ||

| Harris | Erimon? | Ancient Greek? | desert? | Harrey | na Hearadh | Ptolemy's Adru. In Old Norse (and in modern Icelandic), a Hérað is a type of administrative district. Alternatives are the Norse haerri, meaning "hills" and Gaelic na h-airdibh meaning "the heights". |

| Lewis | Limnu | Pre-Celtic? | marshy | Lewis | Leòdhas | Ptolemy's Limnu is literally "marshy". The Norse Ljoðhús may mean "song house" – see above. |

| North Uist | English + Pre-Celtic? | Ywst | Uibhist a Tuath | "Uist" may possibly be "corn island" or "west" | ||

| Scalpay | Skalprey | Norse | scallop island | Scalpay of Harray | Sgalpaigh na Hearadh | |

| South Uist | English + Pre-Celtic? | Uibhist a Deas | See North Uist | |||

| Vatersay | Vatrsey? | Norse | water island | Wattersay | Bhatarsaigh | fathers' island, priest island, glove island, wavy island |

Inner Hebrides Names

Some Inner Hebridean islands had Gaelic names long ago. But these names were completely replaced later. For example, Adomnán wrote about Sainea and Ethica. These names probably stopped being used during the Norse era.

| Island | Derivation | Language | Meaning | Munro (1549) | Modern Gaelic name | Alternative Derivations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canna | Cana | Gaelic | porpoise island | Kannay | Eilean Chanaigh | possibly Old Gaelic cana, "wolf-whelp", or Norse kneøy, "knee island" |

| Coll | Colosus | Pre-Celtic | Colla | possibly Gaelic coll – a hazel | ||

| Colonsay | Kolbein's + ey | Norse | Kolbein's island | Colnansay | Colbhasa | possibly Norse for "Columba's island" |

| Danna | Daney | Norse | Dane island | Danna | Unknown | |

| Easdale | Eisdcalfe | Eilean Èisdeal | Eas is "waterfall" in Gaelic and dale is the Norse for "valley". However the combination seems inappropriate for this small island. Also known as Ellenabeich – "island of the birches" | |||

| Eigg | Eag | Gaelic | a notch | Egga | Eige | Also called Eilean Nimban More – "island of the powerful women" until the 16th century. |

| Eilean Bàn | Gaelic | white isle | Naban | Eilean Bàn | ||

| Eilean dà Mhèinn | Gaelic | |||||

| Eilean Donan | Gaelic | island of Donnán | Eilean Donnain | |||

| Eilean Shona | Gaelic + Norse | sea island | Eilean Seòna | Adomnán records the pre-Norse Gaelic name of Airthrago – the foreshore isle". | ||

| Eilean Tioram | Gaelic | dry island | ||||

| Eriska | Erik's + ey | Norse | Erik's island | Aoraisge | ||

| Erraid | Arthràigh? | Gaelic | foreshore island | Erray | Eilean Earraid | |

| Gigha | Guðey | Norse | "good island" or "God island" | Gigay | Giogha | Various including the Norse Gjáey – "island of the geo" or "cleft", or "Gydha's isle". |

| Gometra | Goðrmaðrey | Norse | "The good-man's island", or "God-man's island" | Gòmastra | "Godmund's island". | |

| Iona | Hí | Gaelic | Possibly "yew-place" | Colmkill | Ì Chaluim Chille | Numerous. Adomnán uses Ioua insula which became "Iona" through misreading. |

| Islay | Pre-Celtic | Ila | Ìle | Various – see above | ||

| Isle of Ewe | Eo | English + Gaelic | isle of yew | Ellan Ew | possibly Gaelic eubh, "echo" | |

| Jura | Djúrey | Norse | deer island | Duray | Diùra | Norse: Jurøy – "udder island" |

| Kerrera | Kjarbarey | Norse | Kjarbar's island | Cearrara | Norse: ciarrøy – "brushwood island" or "copse island" | |

| Lismore | Lios Mòr | Gaelic | big garden/enclosure | Lismoir | Lios Mòr | |

| Luing | Gaelic | ship island | Lunge | An t-Eilean Luinn | Norse: lyng – heather island or pre-Celtic | |

| Lunga | Langrey | Norse | longship isle | Lungay | Lunga | Gaelic long is also "ship" |

| Muck | Eilean nam Muc | Gaelic | isle of pigs | Swynes Ile | Eilean nam Muc | Eilean nam Muc-mhara- "whale island". John of Fordun recorded it as Helantmok – "isle of swine". |

| Mull | Malaios | Pre-Celtic | Mull | Muile | Recorded by Ptolemy as Malaios possibly meaning "lofty isle". In Norse times it became Mýl. | |

| Oronsay | Ørfirisey | Norse | ebb island | Ornansay | Orasaigh | Norse: "Oran's island" |

| Raasay | Raasey | Norse | roe deer island | Raarsay | Ratharsair | Rossøy – "horse island" |

| Rona | Hrauney or Ròney | Norse or Gaelic/Norse | "rough island" or "seal island" | Ronay | Rònaigh | |

| Rum | Pre-Celtic | Ronin | Rùm | Various including Norse rõm-øy for "wide island" or Gaelic ì-dhruim – "isle of the ridge" | ||

| Sanday | Sandey | Norse | sandy island | Sandaigh | ||

| Scalpay | Skalprey | Norse | scallop island | Scalpay | Sgalpaigh | Norse: "ship island" |

| Seil | Sal? | Probably pre-Celtic | "stream" | Seill | Saoil | Gaelic: sealg – "hunting island" |

| Shuna | Unknown | Norse | Possibly "sea island" | Seunay | Siuna | Gaelic sidhean – "fairy hill" |

| Skye | Scitis | Pre-Celtic? | Possibly "winged isle" | Skye | An t-Eilean Sgitheanach | Numerous – see above |

| Soay | So-ey | Norse | sheep island | Soa Urettil | Sòdhaigh | |

| Tanera Mor | Hafrarey | From Old Norse: hafr, he-goat | Hawrarymoir(?) | Tannara Mòr | Brythonic: Thanaros, the thunder god, island of the haven | |

| Tiree | Tìr + Eth, Ethica | Gaelic + unknown | Unknown | Tiriodh | Norse: Tirvist of unknown meaning and numerous Gaelic versions, some with a possible meaning of "land of corn" | |

| Ulva | Ulfey | Norse | wolf island | Ulbha | Ulfr's island |

Uninhabited Island Names

The names of islands where no one lives follow similar patterns. The name "St Kilda" is very complicated. No saint is known by this name. It might come from a Norse phrase meaning "sweet wellwater." Or it could be a mistake about a spring called Tobar Childa. The name "Hirta" is also unclear. It might mean "death" in Old Irish. Or it could come from a Norse word for "stags."

| Island | Derivation | Language | Meaning | Munro (1549) | Alternatives |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ceann Ear | Ceann Ear | Gaelic | east headland | ||

| Hirta | Hirt | Possibly Old Irish | death | Hirta | Numerous – see above |

| Mingulay | Miklaey | Norse | big island | Megaly | "Main hill island". Murray (1973) states that the name "appropriately means Bird Island". |

| Pabbay | Papaey | Norse | priest island | Pabay | |

| Ronay | Norse | rough island | |||

| Sandray | Sandray | Norse | sand island | Sanderay | beach island |

| Scarba | Norse | cormorant island | Skarbay | Skarpey, sharp or infertile island | |

| Scarp | Skarpoe | Norse | "barren" or "stony" | Scarpe | |

| Taransay | Norse | Taran's island | Tarandsay | Haraldsey, Harold's island | |

| Wiay | Búey | Norse | From bú, a settlement | Possibly "house island" |

A Journey Through History

Ancient Times

People first settled in the Hebrides around 6500 BC. This was after the weather became warm enough for humans to live there. One of the oldest signs of people in Scotland is on the island of Rùm. Many structures from the Neolithic period can be found. The most famous are the standing stones at Callanish. These date back to about 3000 BC. At Cladh Hallan on South Uist, prehistoric mummies were found. This is the only place in the UK where this has happened.

Some historians think the stone circle at Callanish might be the "round temple" mentioned by the Greek historian Diodorus Siculus in 55 BC. He wrote about an island called Hyperborea where the moon appeared close to Earth every 19 years.

The first written records of island life begin in the 6th century AD. This is when the kingdom of Dál Riata was formed. It covered parts of Scotland and Ireland. Columba was a very important figure. He founded a monastery on Iona. This helped spread Christianity in northern Britain. Other important sites were on Lismore, Eigg, and Tiree.

North of Dál Riata, the Hebrides were likely under Pictish control. But not much is known about this time.

Viking Rule

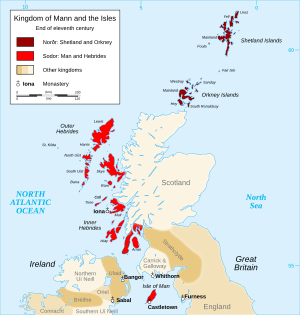

Viking raids started on Scottish shores in the late 700s. The Hebrides soon came under Norse control. This happened especially after Harald Fairhair won the Battle of Hafrsfjord in 872. In the Western Isles, Ketill Flatnose was a powerful leader in the mid-9th century. He built a large island kingdom.

Norse control of the Hebrides became official in 1098. Edgar of Scotland formally gave the islands to Magnus III of Norway. Magnus had conquered Orkney, the Hebrides, and the Isle of Man that same year. He took direct control, but it was a harsh conquest. One of his poets wrote that in Lewis, "fire played high in the heaven" and "flame spouted from the houses."

The Hebrides became part of the Kingdom of the Isles. Its rulers were loyal to the Kings of Norway. This changed in 1156. The Outer Hebrides stayed under Norway. But the Inner Hebrides broke away under Somerled. He was a Norse-Gael leader.

After a failed Norwegian expedition in 1263, the Outer Hebrides and the Isle of Man were given to Scotland. This happened with the Treaty of Perth in 1266. The Vikings left their mark on island names and people's names. But not many Viking objects have been found. The most famous find is the Lewis chessmen. These date from the mid-12th century.

Scottish Control

As Viking rule ended, Norse-speaking leaders were replaced by Gaelic-speaking clan chiefs. These included the MacLeods and Clan Donald. This change did not stop fighting between the clans. But by the early 1300s, the MacDonald Lords of the Isles became powerful. They were based on Islay. They were the feudal superiors of these chiefs.

The Lords of the Isles ruled the Inner Hebrides and parts of the Scottish Highlands. They were subjects of the King of Scots. But John MacDonald, the fourth Lord of the Isles, lost his family's power. A rebellion by his nephew led King James IV to take away their lands in 1493.

In 1598, King James VI allowed some "Gentleman Adventurers" from Fife to "civilise" the "barbarous Isle of Lewis." They were first successful. But local forces drove them out. These forces were led by Murdoch and Neil MacLeod. The colonists tried again in 1605 with the same result. A third try in 1607 was more successful. Stornoway became a town. By this time, the Mackenzies of Kintail owned Lewis. They were more open-minded. They invested in fishing.

Modern Times

After the Treaty of Union in 1707, the Hebrides became part of the new Kingdom of Great Britain. But the clans were not very loyal to the distant king. Many islanders supported the Jacobite rebellions in 1715 and 1745. After the Battle of Culloden, which ended the Jacobite hopes, the British government changed things. They wanted to turn clan chiefs into English-speaking landlords. These landlords would care more about money than their people. This brought peace but at a high cost. The clan system was broken up. The Hebrides became a series of private estates.

The early 1800s saw improvements and population growth. Roads and docks were built. The slate industry grew on Easdale and nearby islands. New canals like the Crinan Canal and Caledonian Canal improved transport. But in the mid-1800s, the Highland Clearances devastated many communities. People were forced off their land to make way for sheep farms. The failure of the kelp industry also made things worse. Many people had to leave the islands.

A Gaelic poet from South Uist, Iain Mac Fhearchair, wrote that leaving was the only choice. He said it was better than "sinking into slavery." In the 1880s, the "Battle of the Braes" was a protest against unfair land rules. This led to the Napier Commission. Problems continued until the Crofters' Act was passed in 1886.

Languages of the Islands

People in the Hebrides have spoken different languages over time. It is thought that Pictish was once spoken in the northern Inner and Outer Hebrides. The Scottish Gaelic language came from Ireland. This was due to the growing power of the kingdom of Dál Riata from the 6th century AD. Gaelic became the main language in the southern Hebrides.

For a few centuries, Old Norse was common in the Hebrides. This was because of the powerful Gall-Ghàidheil. The Old Norse name for the Hebrides was Suðreyjar, meaning "Southern Isles." This was different from the "Northern Isles" of Orkney and Shetland.

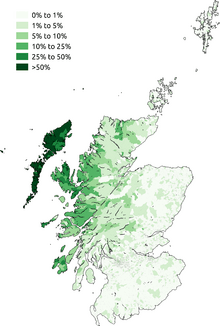

After the 13th century, Gaelic became the main language of all the Hebrides. But because Scots and English were used in government and schools, both languages were present. The Highland Clearances in the 1800s caused fewer people to speak Gaelic. More people moved away, and Gaelic speakers had lower status.

However, even in the late 1800s, many people spoke only Gaelic. The Hebrides still have the highest number of Gaelic speakers in Scotland. This is especially true in the Outer Hebrides, where most people speak the language. The Scottish Gaelic college, Sabhal Mòr Ostaig, is on Skye and Islay.

It's interesting that the Gaelic name for the islands – Innse Gall – means "isles of the foreigners." This name comes from the time when the Norse people colonized them.

Life and Work Today

For those who stayed, new ways to earn money appeared. These included selling cattle, commercial fishing, and tourism. But many people still chose to move away or join the military. The number of people living on the islands kept going down through the late 1800s and most of the 1900s. Many smaller islands became empty.

However, things slowly got better economically. Traditional thatched blackhouse homes were replaced with more modern houses. With help from Highlands and Islands Enterprise, the number of people living on some islands has started to grow again. The discovery of North Sea oil in 1965 and the renewable energy sector have brought some economic stability. For example, the Arnish yard has provided many jobs in both oil and renewable energy.

More people from the mainland, especially those who don't speak Gaelic, have moved to the islands. This has caused some discussion.

Small-scale farming by crofters is still popular in the Hebrides. Crofters own a small piece of land. But they often share a large area for grazing animals. Crofters can get different types of money to help their income. This includes schemes for basic payments and support for cattle and sheep. There are also grants for farming improvements. For example, young crofters can get 80% of investment costs covered, up to £25,000.

Arts, Music, and Stories

Music

Many modern Gaelic musicians come from the Hebrides. These include singer Julie Fowlis (from North Uist) and Catherine-Ann MacPhee (from Barra). Kathleen MacInnes from the band Capercaillie is from South Uist. Ishbel MacAskill is from Lewis. These singers write their own music in Scottish Gaelic. Much of their music comes from Hebridean vocal traditions. These include puirt à beul ("mouth music") and òrain luaidh (waulking songs). This tradition includes many old songs by unknown poets.

The fiddle and violin company Skyinbow is named after and based in Skye. Famous musicians like Mairead Nesbitt and Eileen Ivers have played their instruments. They have also been used in shows like Lord of the Dance and Riverdance.

Literature

The Gaelic poet Alasdair mac Mhaighstir Alasdair lived much of his life in the Hebrides. He often wrote about them in his poems. These include An Airce and Birlinn Chlann Raghnaill. The most famous Gaelic poet of her time was Màiri Mhòr nan Òran (Mary MacPherson, 1821–98). She was from Skye. Her poems showed the spirit of the land protests in the 1870s and 1880s.

Allan MacDonald (1859–1905) lived on Eriskay and South Uist. He wrote hymns and poems. In his plays, he made fun of local gossip and marriage customs.

In the 20th century, Murdo Macfarlane of Lewis wrote Cànan nan Gàidheal. This is a famous poem about the Gaelic language coming back in the Outer Hebrides. Sorley MacLean was a very respected Gaelic writer. He was born and raised on Raasay. His most famous poem, Hallaig, is about the sad effects of the Highland Clearances.

Virginia Woolf's novel To The Lighthouse is set on the Isle of Skye.

Film

- The area around the Inaccessible Pinnacle of Sgurr Dearg on Skye was used for the Scottish Gaelic film Seachd: The Inaccessible Pinnacle (2006).

- An Drochaid is a documentary in Scottish Gaelic. It tells the story of the fight to remove tolls from the Skye bridge.

- The 1973 film, The Wicker Man, takes place on a made-up Hebridean island called Summerisle.

- I Know Where I'm Going! (1945) was filmed on Mull.

Video Games

- The 2012 game Dear Esther is set on an unnamed island in the Hebrides.

- The Hebrides are featured in the 2021 video game Battlefield 2042. They are the setting for the multiplayer map Redacted.

Influence on Visitors

- J.M. Barrie's Marie Rose mentions Harris. He was inspired by a holiday visit to Amhuinnsuidhe Castle. He also wrote a screenplay for the 1924 Peter Pan film while on Eilean Shona.

- The Hebrides, also known as Fingal's Cave, is a famous piece of music. It was composed by Felix Mendelssohn while he was on these islands.

- Enya's song "Ebudæ" is named after the Hebrides.

- The 1973 British horror film The Wicker Man is set on the fictional Hebridean island of Summerisle.

Wildlife and Nature

The Hebrides have fewer types of mammals than mainland Britain. But they are very important breeding grounds for many seabird species. This includes the world's largest group of northern gannets. Other birds include the corncrake, red-throated diver, rock dove, kittiwake, tystie, and Atlantic puffin. You can also see golden eagles and white-tailed sea eagles. The sea eagle was brought back to Rùm in 1975. It has now spread to other islands like Mull. A small number of red-billed choughs live on Islay and Colonsay.

Red deer are common on the hills. Grey seals and common seals live around the coasts. Large groups of seals are found on Oronsay and the Treshnish Isles. The freshwater streams have brown trout, Atlantic salmon, and water shrew. In the sea, you might spot minke whales, orcas, basking sharks, porpoises, and dolphins.

Heather moorland is very common. It has plants like ling, bell heather, and bog myrtle. There are also many Arctic and alpine plants. These include Alpine pearlwort and mossy cyphal.

Loch Druidibeg on South Uist is a national nature reserve. It is managed by Scottish Natural Heritage. The reserve covers 1,677 hectares and has many local habitats. Over 200 types of flowering plants have been found there. Some are rare in the UK. South Uist is considered the best place in the UK for the aquatic plant slender naiad. This plant is a protected species in Europe.

Hedgehogs are not native to the Outer Hebrides. They were brought in during the 1970s to control garden pests. But their spread threatens the eggs of ground-nesting birds. In 2003, Scottish Natural Heritage started removing hedgehogs from the area. This stopped in 2007 due to protests. The trapped animals were moved to the mainland.

See also

In Spanish: Islas Hébridas para niños

In Spanish: Islas Hébridas para niños

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |