St Kilda, Scotland facts for kids

| Gaelic name | Hiort |

|---|---|

| Norse name | Possibly Hirtir |

| Meaning of name | Unknown, possibly Gaelic for "westland" or Norse for "stags" |

Overview of Village Bay, St Kilda |

|

| OS grid reference | NF095995 |

| Coordinates | 57°48′54″N 08°35′15″W / 57.81500°N 8.58750°W |

| Physical geography | |

| Island group | St Kilda |

| Area | 3.3 square miles (8.5 km2) |

| Highest elevation | Conachair, 430 m (1,410 ft) |

| Administration | |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Country | Scotland |

| Council area | Comhairle nan Eilean Siar |

| Demographics | |

| Population | No permanent population since 1930 |

| Largest settlement | Am Baile (the Village) |

| References | |

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

| Criteria | Cultural: iii, v; Natural: vii, ix, x |

| Inscription | 1986 (10th Session) |

| Extensions | 2004, 2005 |

| Area | 24,201.4004 hectares (59,803 acres) |

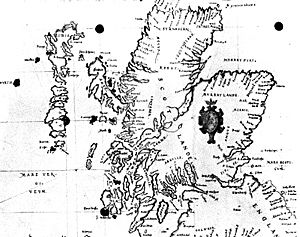

St Kilda (Scottish Gaelic: Hiort) is a group of remote islands far out in the North Atlantic Ocean. It is located about 64 kilometres (40 mi) west-northwest of North Uist in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland. These islands are the westernmost part of Scotland.

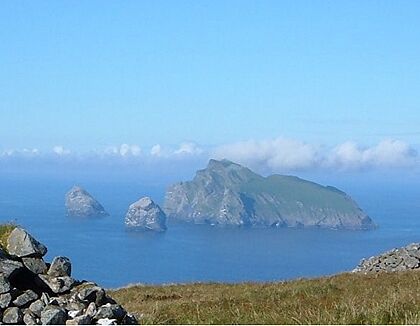

The largest island is Hirta. It has the highest sea cliffs in the United Kingdom. Three other islands, Dùn, Soay, and Boreray, were used for grazing animals and hunting seabirds. St Kilda is part of the Comhairle nan Eilean Siar local government area.

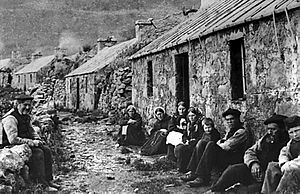

People have lived on these islands for at least 2,000 years. The islands have many unique stone buildings from ancient times. The main village on Hirta was rebuilt in the 1800s. However, new illnesses brought by visitors and the effects of World War I led to the island being emptied in 1930. The story of St Kilda has inspired movies and even an opera.

The population of St Kilda probably never went above 180 people. Most people lived on Hirta. In 1851, there were 112 people. By May 1930, only 36 people remained. On August 29, 1930, all the remaining people were moved from Hirta.

The islands are famous for unique stone structures called cleitean. A cleit is a stone storage hut. Many of these still exist today. There are 1,260 cleitean on Hirta and 170 on the other islands. Today, only military staff live on St Kilda all year. Conservation workers, volunteers, and scientists visit in the summer.

The National Trust for Scotland owns the entire group of islands. In 1986, St Kilda became one of Scotland's six World Heritage Sites. It is one of the few places in the world to be recognized for both its natural beauty and its cultural history. Volunteers work on the islands in summer to fix the old buildings left by the St Kildans. They share the island with a small military base built in 1957.

Two special types of sheep live on these remote islands. The Soay sheep are an ancient type from the Stone Age. The Boreray sheep are from the Iron Age. The islands are also a home for many important seabirds. These include northern gannets, Atlantic puffins, and northern fulmars. The St Kilda wren and St Kilda field mouse are unique kinds of birds and mice found only here.

Contents

What do the names mean?

No saint is known by the name Kilda. Also, the name St Kilda is not used in the local Gaelic language. People have many ideas about where the name came from. It first appeared in the late 1500s.

The name S. Kilda was first seen in a sailing guide from 1592. Some think it was a mistake when copying the name Skilda(r) from an earlier map. On old maps, Skildar meant a group of islands closer to Lewis and Harris. The Norse word skildir means "shields," which could describe islands lying flat on the water.

Another idea is that the name comes from Tobar Childa, an important well on Hirta. Childa comes from the Norse word for a well, kelda. Visitors might have thought it was the name of a local saint.

The name Hiort, and its English form Hirta, are much older than St Kilda. Their meaning is also a bit of a mystery. Some think it comes from a Gaelic word meaning "death." This might refer to the dangers of living on St Kilda. Others think it means "the western land." It might also come from the Norse word hirtir, meaning "stags," because of the islands' jagged shapes.

Island Geography

The islands are made of old volcanic rocks like granite. These rocks have been shaped by the weather over a very long time. The islands are what is left of an ancient volcano that rose from the seabed.

Hirta is the largest island, covering 670 hectares (1,700 acres). This is more than 78% of all the land in the archipelago. Next are Soay (meaning "sheep island") at 99 hectares (240 acres) and Boreray ("the fortified isle") at 86 hectares (210 acres). Soay is about 0.5 kilometres (0.3 mi) northwest of Hirta. Boreray is 6 kilometres (3.7 mi) to the northeast.

Smaller islands and tall rocks called stacks include Stac an Armin ("warrior's stack"), Stac Lee ("grey stack"), and Stac Levenish ("stream" or "torrent"). The island of Dùn ('fort') protects Village Bay from strong winds. Dùn was once connected to Hirta by a natural arch. This arch was likely broken by fierce winter storms.

The highest point in the islands is Conachair ("the beacon") on Hirta, at 430 metres (1,410 ft). This is just north of the village. The north side of Conachair is a vertical cliff, 427 metres (1,401 ft) high, dropping straight into the sea. This is the highest sea cliff in the UK. Boreray reaches 384 metres (1,260 ft) and Soay 378 metres (1,240 ft). Stac an Armin is 196 metres (643 ft) tall, and Stac Lee is 172 metres (564 ft). These are the highest sea stacks in Britain.

In modern times, the only village on St Kilda was at Village Bay (Scottish Gaelic: Bàgh a' Bhaile) on the east side of Hirta. Other old settlements are found in Gleann Mòr on Hirta's north coast and on Boreray.

Even though it is 64 kilometres (40 mi) from the nearest land, St Kilda can be seen from the mountains of Skye, which are 129 kilometres (80 mi) away. The climate is wet and cool, with a lot of rain. Strong winds are common, especially in winter. Landing on the islands can be very difficult due to large ocean waves.

St Kilda is a national nature reserve. It is also a National Scenic Area and a Site of Special Scientific Interest.

Island History

Early History

People have lived on St Kilda for over 2,000 years, from the Bronze Age to the 1900s. In 2015, scientists found pieces of pottery from the Neolithic period (Stone Age). They also found a quarry for stone tools. These tools were found in the cleitean (stone storage buildings) in Village Bay. This suggests people lived here as early as 4,000 BC.

The first written record of St Kilda might be from 1202. An Icelandic writer mentioned taking shelter on "the islands that are called Hirtir." Old Norse place names show that Vikings were present on Hirta. The islands were historically part of the land owned by the Clan MacLeod.

In 1615, Coll MacDonald of Colonsay raided Hirta. He took 30 sheep and some barley. Later, the islands became known for having plenty of food. In 1697, the population was 180. The landlord's helper would bring people from other islands to St Kilda to get healthy from the good food.

Changes and Challenges

Ships visiting the islands in the 1700s brought diseases like cholera and smallpox. In 1727, so many people died that new families had to be brought from Harris. By 1758, the population was 88. It stayed around 100 until 1851. That year, 36 islanders moved to Australia. The island never fully recovered from this loss.

A missionary named Alexander Buchan visited St Kilda in 1705. But organized religion did not really take hold until Rev. John MacDonald arrived in 1822. He preached many long sermons. He also raised money for the St Kildans. His successor, Rev. Neil Mackenzie, arrived in 1830. He greatly improved life on the islands. He helped rebuild the village and built a new church. He and his wife also started formal education, teaching reading, writing, and math.

After Mackenzie left in 1844, no new minister came for ten years. The school closed. In 1865, Rev. John Mackay arrived. He made religious services very strict. People had to attend three long services on Sunday. It was considered wrong to look around or make noise. This strictness made life difficult and interfered with daily tasks. For example, when a relief ship arrived on a Saturday during a food shortage, the minister said the islanders had to prepare for church. Supplies were not unloaded until Monday.

Daily Life

Life on St Kilda was very isolated. Travel by boat was difficult and dangerous, especially in autumn and winter. Storms were common between September and March. Winds could reach 144 mph (125 kn).

The islanders knew little about the outside world. After a battle in 1746, soldiers came to St Kilda looking for a prince. They found the St Kildans had never heard of the prince or the king.

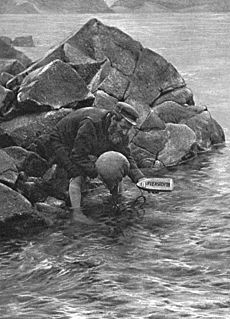

Even in the late 1800s, the islanders could only contact the mainland by lighting a bonfire. Or they used the "St Kilda mailboat." This was an idea from a visitor named John Sands. He attached a message to a lifebuoy and threw it into the sea. It was found nine days later. The St Kildans then made small wooden boats with sheepskin bladders. They put messages in bottles inside and launched them when the wind was right. About two-thirds of these messages were found in Scotland or Norway.

Food and Traditions

The St Kildans raised sheep and some cattle. They also grew small amounts of crops like barley and potatoes. They did not fish much because of the rough seas. Their main food came from seabirds, especially gannets and fulmars. They collected eggs and young birds. They ate them fresh or preserved them.

This diet meant the air often smelled strongly of birds and fish. Old tools found on the island show that this diet had not changed for thousands of years. The islanders collected eggs by climbing down dangerous cliffs.

Climbing was a very important skill. Young men had to perform a ritual at the "Mistress Stone" to prove they were worthy of marriage. This stone was a door-shaped opening in the rocks high above a gully.

Another important part of St Kildan life was the daily "parliament." This was a meeting of all adult men after morning prayers. They would decide what to do that day. Everyone had a right to speak. Even though there were disagreements, the community always stayed together. This idea of a free society influenced the design of the new Scottish Parliament Building.

The St Kildans' isolation protected them from some problems of the outside world. They were considered happier and freer than many other people. No St Kildan is known to have fought in a war. No serious crime was ever recorded there.

Tourism and the War

In the 1800s, steamships started visiting Hirta. This allowed the islanders to sell things like wool and bird eggs. But it also made them feel like curiosities to the tourists. The boats also brought new diseases, especially one that caused many baby deaths.

By the early 1900s, formal schooling returned. Children learned English and their native Gaelic. Better medical care helped reduce childhood illnesses. Fishing boats also started visiting, bringing more trade. The population was stable at about 75 to 80 people. No one expected that the island's long history of people living there would soon end.

First World War and Evacuation

During World War I, the British Navy built a signal station on Hirta. This brought daily communication with the mainland for the first time. In 1918, a German submarine attacked Village Bay. It fired 72 shells, destroying the wireless station and damaging buildings. No one was killed, but one lamb died.

After this attack, a large gun was placed on a cliff overlooking Village Bay. It was never used. The war brought regular contact with the outside world. It also slowly introduced a money-based economy. This made life easier but also made the St Kildans less able to rely on themselves. These changes led to the island's evacuation a decade later.

When the war ended, many young men left the island for better lives. The population dropped from 73 in 1920 to 37 in 1928. After four men died from influenza in 1926, there were several years of bad harvests. Studies show that the soil was polluted from using seabird remains and peat ash as fertilizer. This might have been a reason for the evacuation.

The final decision to leave came after a young woman, Mary Gillies, died in 1930. She had appendicitis and was taken to the mainland, where she died of pneumonia. Two days before the evacuation, all the cattle and sheep were taken off the island. The working dogs were drowned because they could not be taken. Cats were left behind, but many died. In 1931, the remaining cats were shot to protect the birds.

On August 29, 1930, the ship Harebell took the remaining 36 people to the Scottish mainland. This was a decision they made together. The islanders left an open Bible and oats in each house. They locked their doors. As the island faded from view, the St Kildans began to cry.

The last native St Kildan, Rachel Johnson, died in 2016 at age 93. She was eight years old when she was evacuated. In 1931, the island's owner sold St Kilda to Lord Dumfries. For the next 26 years, few people visited.

Military Presence

St Kilda was not used during World War II. However, three aircraft crashed there during that time. In 1955, the British government decided to use St Kilda for a missile tracking range. So, in 1957, St Kilda became permanently inhabited again. Military buildings and masts were built. The Ministry of Defence (MOD) rents St Kilda from the National Trust for Scotland.

Hirta is still occupied all year by a small number of civilians. They work for a defense company at the military base. In 2018, the MOD facilities were being updated. The island population can be between 20 and 70 people, including MOD staff, National Trust for Scotland staff, and scientists.

St Kilda Today

Before the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, tourists were encouraged to visit St Kilda. However, facilities like toilets and campsites were closed in early 2021.

The National Trust for Scotland has improved the village on Hirta. They have put new roofs on the cottages and fixed the church. They have also rebuilt the stone cleitean that had fallen apart. One cottage, number 3, has been fully restored and is now a museum.

The church and schoolroom were restored to look like they did in the 1920s. The village street was arranged in the mid-1800s. The unique drystone storage buildings, called cleitean, are found all over the islands. There are over 1,400 cleitean on the St Kilda islands.

The National Trust for Scotland says that many people are interested in diving and seeing seabirds here. St Kilda is Europe's most important seabird colony. Day trips by boat from Skye were available before the closures. Landing at the pier can be hard in rough seas.

Island Buildings

Ancient Buildings

The oldest buildings on St Kilda are a bit of a mystery. Large sheep pens are found inland from the village. They have strange "boat-shaped" stone rings. These might be from 1850 BC, but their purpose is unknown. In Gleann Mòr, there are 20 "horned structures." These are ruined buildings with curved walls. Nothing like them exists anywhere else in Europe. Their original use is also unknown.

Also in Gleann Mòr is Taigh na Banaghaisgeich, the "Amazon's House." Old stories say a female warrior lived here. This stone house is built in a circle, like a pyramid, with a hole for smoke. It has three small sleeping areas. The stories say she hunted on land that is now underwater between the islands and Harris.

Much more is known about the hundreds of unique cleitean. These dome-shaped buildings are made of flat stones with turf on top. Wind can pass through the walls, but rain stays out. They were used to store peat, nets, grain, meat, eggs, and hay. They also sheltered lambs in winter. These buildings were used from ancient times until the 1930 evacuation. Over 1,200 ruined or complete cleitean are on Hirta. Another 170 are on nearby islands.

Medieval Village

A medieval village was located near Tobar Childa, about 350 metres (1,150 ft) from the shore. The oldest building there is an underground passage called Taigh an t-Sithiche (house of the faeries). It dates from between 500 BC and 300 AD. The St Kildans thought it was a house or hiding place. A newer idea is that it was an ice house.

There are many ruined walls and cleitean from this time. There is also a medieval "house" with a beehive-shaped room. Nearby is the "Bull's House," where the island's bull was kept in winter. Tobar Childa is a spring that provided water. A wall, called the Head Wall, was built around the village to keep sheep and cattle out of the farmed areas. There were 25 to 30 houses, mostly blackhouses. Some older buildings were made of stone and covered with turf.

Later Buildings

The Head Wall was built in 1834. The medieval village was left, and a new one was planned closer to the sea. A visitor, Sir Thomas Dyke Ackland, was shocked by the poor conditions. He gave money to build 30 new blackhouses. These houses had thick stone walls and turf roofs. They had small windows and a hole for smoke from the peat fire. Cattle lived at one end of the house in winter.

In 1860, a strong storm damaged some of the new houses. Later, around 1862, sixteen modern cottages with zinc roofs were built.

One sad ruin on Hirta is "Lady Grange's House." Lady Grange was secretly held on St Kilda from 1734 to 1740. She said it was a "vile neasty, stinking poor isle." The "house" named after her is a large cleit in the village fields.

Attempts were made to improve the landing area by blasting rocks in the 1860s. A small jetty was built in 1877 but was washed away by a storm two years later. A new one was completed in 1902.

At one time, three churches were on Hirta. Christ Church was the largest. St Brendan's Church and St Columba's were also there, but little remains of them. A new church and minister's house were built in 1830. A house for the landlord's agent was built in 1860.

Buildings on Other Islands

On Dùn, there is a ruined wall of a fort. The only "house" is Sean Taigh (old house), a natural cave used by St Kildans. Soay has a simple hut called Taigh Dugan. This is just a hole under a large stone.

Boreray has the Cleitean MacPhàidein, a "cleit village" of three small huts. These were used regularly during bird hunting trips. There are also the ruins of Taigh Stallar (the steward's house). This was similar to the Amazon's house. It might be an Iron Age wheelhouse. About 78 storage cleitean are on Stac an Armin, and a small hut is on Stac Lee. These were also used by bird hunters.

Animals and Plants

Wildlife on St Kilda

St Kilda is a very important place for many seabirds to have their young.

- It has one of the world's largest groups of northern gannets, with 30,000 pairs. This is 24% of all gannets in the world.

- There are 49,000 breeding pairs of Leach's petrels, which is up to 90% of the European population.

- About 136,000 pairs of Atlantic puffins live here, which is about 30% of the UK's total.

- There are 67,000 northern fulmar pairs, about 13% of the UK's total.

Dùn has the largest group of fulmars in Britain. The last great auk seen in Britain was killed on Stac an Armin in 1840. St Kilda is recognized as an Important Bird Area for its seabird colonies.

Two types of wild animals are found only on St Kilda:

- The St Kilda wren (a type of Eurasian wren).

- The St Kilda field mouse (a type of wood mouse).

A third type, the St Kilda house mouse, disappeared after people left the island. Grey seals now have their young on Hirta.

Because the islands are so isolated, there are not many different kinds of plants and animals. Flies are the most common insects, followed by beetles. There are no bees on the islands. One rare beetle is found only on Dùn and the Westmann Islands near Iceland. Fewer than 100 types of butterflies and moths live here.

The plants are affected by salt spray, strong winds, and peaty soil. No trees grow on the islands. But there are over 130 different flowering plants, many fungi, and mosses. The St Kilda dandelion is a unique type of dandelion found only here.

The beach at Village Bay is unusual. Its sand disappears in winter, showing the large rocks underneath.

Soay Sheep

On the island of Soay, there is a unique type of sheep. These Soay sheep are believed to be like the earliest sheep kept in Europe during the Stone Age. They are small, have short tails, and are usually brown with white bellies. Their wool sheds naturally. About 200 Soay sheep live on Soay. After the evacuation, a second group was started on Hirta. These sheep are valued for being tough and having an unusual look.

The St Kildans used to keep up to 2,000 different sheep on Hirta and Boreray. These were a type of Scottish Dunface sheep, similar to those kept in Britain during the Iron Age. When the island was evacuated, all the islanders' sheep were removed from Hirta. But the sheep on Boreray were left to become wild. These sheep are now their own breed, called the Boreray. They are one of the rarest British sheep.

Protecting Nature

When the Marquess of Bute died in 1956, he left the islands to the National Trust for Scotland. They accepted the gift in 1957. Work began to fix and protect the village. Volunteers help with this work in the summer. Scientists also study the wild Soay sheep and other parts of nature. In 1957, the area was named a national nature reserve.

In 1986, St Kilda became the first place in Scotland to be named a UNESCO World Heritage Site. This was for its natural features. In 2004, the World Heritage Site was made larger to include the surrounding sea. In 2005, St Kilda became one of only about two dozen places in the world to be recognized for both its "natural" and "cultural" importance.

St Kilda is also a Scheduled Ancient Monument, a National Scenic Area, and a Site of Special Scientific Interest. Visitors who want to land on the islands need to contact the National Trust for Scotland first. People are careful to prevent new animals or plants from coming to the islands. This is because the environment is very delicate. In 2008, a fishing boat ran aground on Hirta. There was worry that rats from the boat could harm the birds. Luckily, the boat's fuel and other items were removed before the bird breeding season.

St Kilda's underwater caves and arches offer a challenging but amazing diving experience. The strong ocean waves can be felt 70 metres (230 ft) below the surface.

See also

In Spanish: San Kilda para niños

In Spanish: San Kilda para niños