Stac an Armin facts for kids

| Gaelic name | Stac an Àrmainn |

|---|---|

| Meaning of name | (Gaelic) "stack of the warrior" |

| OS grid reference | NA151064 |

| Coordinates | 57°53′N 8°29′W / 57.88°N 8.49°W |

| Physical geography | |

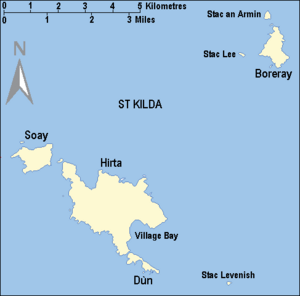

| Island group | St Kilda |

| Area | 9.9 ha (24 acres) |

| Highest elevation | 196 m (643 ft) |

| Administration | |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Country | Scotland |

| Council area | Outer Hebrides |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 0 |

Stac an Armin (in Scottish Gaelic: Stac an Àrmainn) is a very tall, thin island called a sea stack. It is part of the St Kilda group of islands. This amazing stack stands 196 meters (643 feet) high! This makes it a "Marilyn," which is a special name for hills over a certain height. It is actually the tallest sea stack in all of Scotland and the British Isles.

The name Stac an Armin means "stack of the soldier" or "warrior" in Scottish Gaelic. Long ago, people from nearby islands used it to hunt birds. They didn't live there all year, but sometimes people got stuck there for a while! People used to climb the rocks to collect bird eggs. Today, some people still climb it for fun and sport. This island was once home to the great auk, a bird that is now extinct. Special rules are in place to protect the birds that live and breed there today.

Stac an Armin is about 400 meters (a quarter of a mile) north of Boreray. It is also close to another tall stack called Stac Lee, which is 172 meters (564 feet) high. The water between Stac an Armin and Boreray is full of rocks. Because of this, boats usually do not sail through it. However, sailors often talk about the amazing views they get of these islands!

Contents

Life on Stac an Armin: History and People

The first time anyone wrote about Stac an Armin was in the early 1700s. A Scottish writer named Martin Martin visited St Kilda in 1697. He wrote about the stack in his book, A Description of the Western Isles of Scotland, published in 1703. This was the first detailed book about the islands. Martin called the stack "Stack-Narmin."

People never lived on Stac an Armin all the time. However, hunting birds there was very important for the people of St Kilda. It helped them get enough food to live. You can still see buildings they left behind. There are at least 78 storage huts called "cleitean" on Stac an Armin. There is also a small shelter, or "bothy," built by the St Kildans. Martin described these cleitean as "pyramids." He said they were used to "preserve and dry" birds, especially the "solan goose" (which is a northern gannet). Martin once saw a harvest where people collected 800 birds! Besides geese, islanders also hunted great auks, gannets, and puffins on Stac an Armin. They also collected their eggs. All these birds were a very important food source for the people of St Kilda.

Stuck on the Stack: An Unplanned Stay

The longest time anyone ever spent on Stac an Armin was about nine months. This happened to three men and eight boys from Hirta, another island in St Kilda. They were stuck there from August 15, 1727, until May 13, 1728. Sadly, a sickness called smallpox broke out on Hirta while they were on the stack. Because of this, the islanders couldn't send a boat to get them until the next year.

It seems that people getting stuck on the island by accident might have happened often. Martin Martin also wrote a story about it. He told how about twenty men were stranded on the island for a few days. The rope holding their boat broke. They survived by fishing. They let their wives know they were okay by lighting "as many fires on the top of an eminence as there were men in number." Martin added that the wives were so happy, they had a record harvest of corn that year!

The people of St Kilda left all the islands in 1930. In 1957, the islands were given to the National Trust for Scotland. Hunting birds is no longer allowed. Today, only scientists, journalists, and climbers visit the stack sometimes.

The Last Great Auk in Britain

Something very important happened on Stac an Armin in July 1840. The very last great auk (Pinguinus impennis) seen in Britain was caught and killed there. A 75-year-old man from St Kilda told a visitor that he, his father-in-law, and another man caught a "garefowl." They noticed its small wings and a large white spot on its head. They tied it up and kept it alive for three days. Then, they sadly killed it by hitting it with a stick. They believed it was a witch. The last great auks known in the world were killed a few years later in Eldey, Iceland, or off Newfoundland.

Climbing Stac an Armin

The native people of St Kilda climbed Stac an Armin and other cliffs for hundreds of years. They did this to collect birds and eggs. They climbed in a special way, often barefoot or in thick socks. They used ropes made from horse hair. Today, not many people climb Stac an Armin. Some climbs might even have been done without permission.

Climbing Stac an Armin is very challenging. It's described as "little easier than Stac Lee." The way the land is shaped makes it a "major expedition." Also, the weather can make it impossible to land a boat there. It's very hard to get to the stack.

The entire St Kilda group of islands is a special place. It is both a national nature reserve and a World Heritage Site. This is mainly because of its cliffs and huge seabird colonies. Scottish Natural Heritage (SNH) manages the area. Climbing is very strictly controlled because it could disturb the nature and history, especially the many birds. The rules say that nature should usually be left alone.

The rules are very clear about the dangers of climbing in St Kilda. One rule is to "Ensure that breeding seabirds are not disturbed by climbing on the cliffs." However, the plan also suggests that climbing might be allowed under very strict conditions. Another rule says that a plan should be made that works for climbers but also protects the islands. The National Trust for Scotland has a very clear rule about climbing:

Given the difficulty of the climbs, the lack of any rescue or medical facilities on St Kilda and the risk of disturbance to nesting bird on the cliffs, climbing on St Kilda is not permitted without the express permission of the Trust. This is stated formally under the St Kilda Bylaws (No 10). As part of the process of implementing this Management Plan, the Trust will liaise with SNH and the Mountaineering Council of Scotland to review whether any change is merited to this position.

The Mountaineering Council of Scotland has suggested that the National Trust for Scotland should celebrate the important history of climbing on the St Kilda islands.

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |