Razorbill facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Razorbill |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| On Skomer Island, Pembrokeshire, Wales | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Charadriiformes |

| Family: | Alcidae |

| Genus: | Alca |

| Species: |

A. torda

|

| Binomial name | |

| Alca torda Linnaeus, 1758

|

|

| Subspecies | |

|

|

|

|

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

The razorbill (Alca torda) is a cool seabird found in the North Atlantic Ocean. It lives in groups and is the only living member of its bird family, the auks. The razorbill is a close cousin to the great auk, which is now extinct.

Razorbills are mostly black with a white belly. Both male and female razorbills look alike, but males are usually a bit bigger. These birds are great at both flying and diving! They spend most of their lives in the water. They only come to land to have their babies. Razorbills choose one partner for life. Females lay one egg each year. They build their nests on coastal cliffs in hidden spots. Both parents take turns sitting on the egg. Once the chick hatches, they both help find food for it.

Since 1918, the razorbill has been protected in the United States. Today, these birds face big challenges. Their nesting places are sometimes destroyed. Oil spills are also a threat. The quality of their food can also get worse. The number of razorbills changes over time. It went up from 2008 to 2015. Then it went down until 2021. Now, their numbers seem to be growing or staying steady. Experts think there are between 838,000 and 1,600,000 razorbills in the world.

Contents

About Razorbill Names

The name Alca for this type of bird was first used in 1758. It was named by a Swedish scientist named Carl Linnaeus. The name Alca comes from a Norwegian word, and torda comes from a Swedish word. Both words refer to this bird.

The razorbill (Alca torda) is the only bird left in its group, Alca. Its close relative, the great auk, died out in the mid-1800s. Razorbills and great auks belong to a larger bird group called Alcini. This group also includes the common murre and the thick-billed murre.

There are two main types of razorbills. Scientists call these "subspecies."

| Image | Subspecies | Where They Live |

|---|---|---|

|

Alca torda torda | They live in the Baltic Sea, White Sea, Norway, Iceland, Greenland, and eastern North America. |

|

Alca torda islandica | They live in Ireland, Great Britain, and northwestern France. |

These two types of razorbills have slightly different sized beaks.

What Razorbills Look Like

During breeding season, the razorbill has a white belly. Its head, neck, back, and feet are black. A thin white line goes from its eyes to the end of its beak. Its head is darker than a common murre's. When it's not breeding season, its throat and the area behind its eye turn white. The white line on its face also becomes less clear.

The razorbill's beak is black and strong. It has a few grooves near the curved tip. One of these grooves has a broken white line. The beak looks thinner and has fewer grooves when it's not breeding season. Razorbills are large, sturdy birds. They usually weigh between 505 and 890 grams (about 1.1 to 1.9 pounds). Males and females look very similar. They only have small differences, like wing length.

A razorbill is about 37–39 cm (14.5–15.3 inches) long. The wings of adult males are 201–216 mm (7.9–8.5 inches) long. Female wings are 201–213 mm (7.9–8.3 inches) long. When sitting on its nest, the razorbill stands horizontally. Its tail feathers are a bit longer in the middle. This gives the razorbill a long tail, which is unusual for an auk. When flying, their feet do not stick out past their tail.

Razorbills choose one partner for life. They build their nests in hidden spots on cliffs or among rocks. They are social birds and only come to land to breed. A razorbill usually lives for about 13 years. But one bird in the UK lived for at least 41 years! That's a record for its kind.

Where Razorbills Live

Razorbills live across the North Atlantic Ocean. There are fewer than 1,000,000 breeding pairs in the world. About half of these pairs live in Iceland. Razorbills like water that is cooler than 15 °C (59 °F). They are often seen with other large auks. But unlike other auks, they often go into big river mouths to find food. These areas have less salty water.

These birds live in the colder waters of the Atlantic. They breed on islands, rocky shores, and cliffs. In eastern North America, they go as far south as Maine. In western Europe, they go from northwestern Russia to northern France. Birds from North America fly south for winter. They go from the Labrador Sea to New England. Birds from Europe also spend winter at sea. Many gather in the North Sea. Some even go as far south as the western Mediterranean. About 60 to 70% of all razorbills breed in Iceland.

Here are some places where razorbills live in colonies:

- Grímsey, Iceland

- Látrabjarg, Iceland (a very large colony with 230,000 pairs)

- Runde, Norway

- St Kilda, Scotland

- Staple Island, UK

- Bempton Cliffs, UK

- Skomer Island, Pembrokeshire, Wales

- Heligoland, Germany (a few pairs, near their southern limit)

- Gannet Islands, Canada

- Funk Island, Canada

- Baccalieu Island, Canada

- Witless Bay, Canada

- Cape St. Mary's, Canada

Razorbill Behavior

Razorbills act a lot like the common murre. But razorbills are a bit more agile. They are migratory birds. This means they leave land during colder months. They spend the entire winter in the Atlantic Ocean.

During breeding season, both male and female razorbills protect their nest. Females choose their mate. They sometimes make males compete before picking a partner. Once a male is chosen, the pair stays together for life.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Razorbills start breeding when they are 3–5 years old. As they get older, they might skip a year of breeding. Mating pairs will "court" each other many times. This helps them strengthen their bond. They touch beaks and fly together in fancy patterns.

Before the female lays her egg, the male will guard her. He will push other males away with his beak. The pair will mate many times to make sure the egg is fertilized. Sometimes, females will even mate with other males. This is to make sure they have a successful baby.

During this time, razorbills gather in large groups. They socialize in two ways. First, big groups dive and swim in circles. Then they all pop up to the surface with their heads first and beaks open. Second, large groups swim in a line, weaving past each other in the same direction.

Nest Sites

Choosing a nest site is very important for razorbills. It helps keep their young safe from predators. Unlike murres, razorbills don't nest right on open cliff ledges. They choose hidden spots. Nests are usually in cracks in cliffs or among rocks. Some nests are on ledges, but hidden spots are safer.

The mating pair often uses the same nest site every year. Baby chicks can't fly. So, nests close to the sea make it easy for them to leave the colony. Razorbills usually don't build a fancy nest. But some pairs use their beaks to gather materials for their egg. They might nest under a large rock. They rarely use an open ledge. They might even use a puffin or rabbit burrow. Razorbills live in groups, but their nests are not right next to each other. They are a few meters apart. This means there is less fighting than in other bird colonies.

Incubation and Hatching

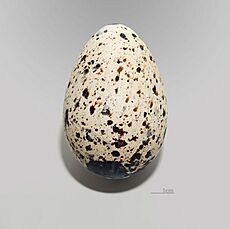

Females lay only one egg each year. This usually happens from late April to May. The egg is shaped like an oval pyramid. It is cream-colored with dark brown spots. The parents start sitting on the egg about two days after it is laid. Both females and males take turns. They sit on the egg for about 35 days until it hatches.

Razorbill chicks are born somewhat developed. For the first two days, the chick stays mostly under a parent's wing. One parent always stays at the nest. The other goes to the sea to find food for the chick. The chick grows all its feathers about 10 days after hatching. After 17–23 days, the chick leaves the nest. It jumps from the cliff. The male parent follows it closely. He will go with the chick to the sea. During this time, the male parent dives more than the female.

Feeding Habits

Razorbills dive deep into the sea. They use their partly folded wings and sleek bodies to swim fast. They spread their feet out. When diving, they usually spread out to find food. They don't stay in groups. Most of their feeding happens at a depth of 25 meters (about 82 feet). But they can dive up to 120 meters (about 394 feet) deep! In one dive, a bird can catch and eat many small fish. This depends on the fish size. Razorbills spend about 44% of their time looking for food at sea.

When feeding their young, they usually bring small amounts of food. Adults mostly bring one fish at a time to their chick. They bring the most food at dawn. They bring less food about 4 hours before dark. Females usually feed their chicks more often than males. When they are sitting on eggs, they might fly more than 100 km (62 miles) out to sea to find food. But when they have chicks, they look for food closer to the nest. This is usually about 12 km (7.5 miles) away. They often look in shallower water.

What Razorbills Eat

The razorbill's diet is very similar to that of a common murre. They mostly eat small fish that swim in groups. These include fish like capelin, sand lance, young cod, sprats, and herring. They might also eat crustaceans (like crabs or shrimp) and polychaetes (a type of worm). What razorbills eat can change based on the ocean conditions where they live.

Predators of Razorbills

Adult razorbills have several predators. These include polar bears, great black-backed gulls, peregrine falcons, ravens, crows, and jackdaws. The main predators of their eggs are gulls and ravens. The best way for an adult razorbill to escape danger is by diving into the water. Arctic foxes can also eat many adult birds, eggs, and chicks in some years.

In the past, people in Scotland's St Kilda islands collected razorbill eggs. They would climb cliffs to get them. The eggs were stored in peat ash to be eaten during the cold winters. People said the eggs tasted like duck eggs.

Protecting Razorbills

In the early 1900s, people hunted razorbills. They took their eggs, meat, and feathers. This caused their numbers to drop a lot. In 1917, the "Migratory Bird Treaty Act" finally protected them. This helped reduce hunting.

Other dangers include oil pollution. Oil spills can harm their breeding sites. Damage to these sites means fewer places for them to nest. This affects how many babies they can have. Commercial fishing also hurts razorbill populations. Razorbills can get caught in fishing nets. Too much fishing also means less food for razorbills. This makes it harder for them to survive.

Ancient Razorbills

While the razorbill is the only living species today, there were many more types of Alca birds long ago. This was during a time called the Pliocene. Some bird experts even think the great auk should still be in the Alca group. Scientists have found fossils of several ancient Alca birds.

The Alca group seems to have first appeared in the western North Atlantic. This is where most other Alcini birds also began. Their ancestors likely reached these waters through the Isthmus of Panama, which was still open during the Miocene era.

Images for kids