Thick-billed murre facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Thick-billed murre |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Adults in breeding plumage | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Charadriiformes |

| Family: | Alcidae |

| Genus: | Uria |

| Species: |

U. lomvia

|

| Binomial name | |

| Uria lomvia (Linnaeus, 1758)

|

|

| Subspecies | |

|

U. l. lomvia – (Linnaeus, 1758) |

|

|

|

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Alca lomvia Linnaeus, 1758 |

|

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

The thick-billed murre or Brünnich's guillemot (Uria lomvia) is a type of bird. It belongs to the auk family, called Alcidae. This bird got its name from a Danish zoologist, Morten Thrane Brünnich. There's a special kind of thick-billed murre found in the North Pacific called Uria lomvia arra. People also call it Pallas' murre after the person who first described it, Peter Simon Pallas.

These birds are known for having the highest flight cost for their size. This means they use a lot of energy to fly compared to other animals of similar size.

Contents

What Thick-billed Murres Look Like

The thick-billed murre is one of the largest living members of the auk family. The only larger one, the great auk, is now extinct. Thick-billed murres are similar in size to the common guillemot, but they are usually a bit bigger.

These birds are about 40–48 cm (16–19 in) long. Their wings can spread out to 64–81 cm (25–32 in). They weigh between 736–1,481 g (26.0–52.2 oz). The murres living in the Pacific Ocean are larger than those in the Atlantic Ocean.

Adult thick-billed murres have black heads, necks, backs, and wings. Their undersides are white. They have a long, pointed bill and a small, round black tail. In winter, the lower part of their face turns white. When they are at their breeding colonies, they make loud, harsh calls. But when they are out at sea, they are quiet.

You can tell them apart from common murres by their thicker, shorter bill. They also have a white stripe near their mouth. Their head and back are darker. Unlike common murres, thick-billed murres do not have a white stripe above their eye. In winter, they have less white on their face. When they fly, they look shorter than common murres. Young birds have smaller bills, and the white stripe on their bill is often hard to see. So, the best way to identify young birds is by their head pattern.

Where Thick-billed Murres Live

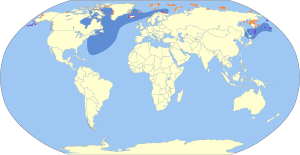

Thick-billed murres live in the cold, polar and sub-polar areas of the Northern Hemisphere. There are four different types, or subspecies, of these birds:

- One lives in the Atlantic and Arctic parts of North America.

- Another lives along the Pacific coast of North America.

- The other two live in the Russian Arctic.

These birds spend their entire lives at sea. They prefer waters that stay below 8°C. The only time they come to land is during the breeding season. They gather in large groups on cliffs to lay their eggs.

Thick-billed Murre Reproduction and Life Cycle

Thick-billed murres form huge breeding colonies. These colonies can have over a million birds. They nest on narrow ledges and steep cliffs that face the water. They need very little space, less than one square foot per bird.

Each breeding pair lays only one egg per year. Even so, they are one of the most common sea birds in the Northern Hemisphere. Early in the breeding season, adult birds perform special group displays. This helps them get ready to breed at the same time. They do not build nests. Instead, they lay their egg directly on the bare rock. Both parents take turns sitting on the egg to keep it warm. They also both help raise the young chick.

Flying takes a lot of energy for adult murres. Because of this, they can only bring one piece of food to their chick at a time. Chicks stay on the cliffs for 18 to 25 days. When they are ready to leave, they wait until nightfall. Then, they jump off the cliff edge towards the water. One parent immediately jumps after them. The adult glides down very close to the young bird. Once they are in the sea, the male parent and the chick stay together for about 8 weeks. During this time, the adult continues to feed the young bird.

The survival of young murres depends on the age of the parents. Chicks from new parents grow more slowly. This might be because they don't get as much food. Also, pairs with at least one young parent have fewer eggs hatch. Older, more experienced adults get the best nesting spots. These are usually in the center of the colony. Younger, less experienced birds are on the edges. Their chicks are more likely to be eaten by predators.

Migration Patterns

Thick-billed murres move south in winter. They go to the northern parts of the Atlantic Ocean and Pacific Ocean. They only move far enough to stay in waters that are free of ice.

Flight and Feeding Habits

The thick-billed murre flies strongly and directly. They beat their short wings very fast. Like other auks, these birds find food by using their wings to 'swim' underwater. They are excellent divers. They can dive up to 150 meters deep and stay underwater for a long time. Their strong flight uses a lot of energy. In fact, for their body size, it's the most energy-costly way to move for any animal.

Scientists believe that murres and similar auks have a special way to avoid problems from diving deep. They might temporarily store extra gases in their bones. This allows the gases to be released slowly as they come back to the surface. This helps them avoid issues like diving sickness or lung collapse.

What Thick-billed Murres Eat

The main type of thick-billed murre eats mostly fish. This includes fish like Gadus spp. and Arctic cod. They also eat small ocean creatures called amphipods. Other foods like capelin fish, other crustaceans, worms, and some molluscs are also part of their diet, but in smaller amounts. When they spend winter near Newfoundland, capelin can make up over 90 percent of their food.

Thick-billed murres have few natural predators. This is because so many birds gather in their breeding colonies. Also, these nesting sites are hard for predators to reach. Their main predator is the glaucous gull. These gulls only eat murre eggs and chicks. The common raven might also try to take eggs and young birds if they are left alone.

Status and Conservation

Even though their numbers have gone down in some areas, the thick-billed murre is not currently in danger. It's estimated that there are between 15 and 20 million of these birds worldwide.

In Greenland, people used to collect their eggs and hunt adult birds. This caused their populations to drop a lot between the 1960s and 1980s. In parts of Russia, their numbers have also decreased. This is due to human activities near polar stations. Fishing can also be a threat. However, thick-billed murres can find other food sources, so fishing doesn't affect them as much as it does common murres.

Oil spills in the ocean are another big danger. Murres are very sensitive to oil pollution. They can also get caught in fishing nets, which is another reason their populations decline.

Thick-billed murres rely on sea ice all year round. Some scientists worry that climate change could be a threat to these Arctic birds. However, the birds seem able to adapt. In warmer areas, they have switched from eating Arctic cod (which lives near ice) to capelin (which prefers warmer water). They also lay their eggs earlier when the ice breaks up earlier. In very warm years, mosquitoes and heat can even kill some adult birds.

Birds That Wander Far From Home

Brünnich's guillemot sometimes wanders far from its usual breeding areas. It's rare to see them in European countries south of their normal range. In Britain, over 30 have been seen, but most were found dead. Only a few live ones have stayed long enough for many people to see them. All three of these were in Shetland.

This bird has been seen once in Ireland and also in the Netherlands. In the western Atlantic, they can travel as far south as Florida. In the Pacific, they can reach California. Before 1950, many of these birds used to appear in the North American Great Lakes during early winter. They would travel up the St. Lawrence River from the East coast. But these large groups haven't been seen since 1952.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Arao de Brünnich para niños

In Spanish: Arao de Brünnich para niños

| Shirley Ann Jackson |

| Garett Morgan |

| J. Ernest Wilkins Jr. |

| Elijah McCoy |