St. Lawrence Iroquoians facts for kids

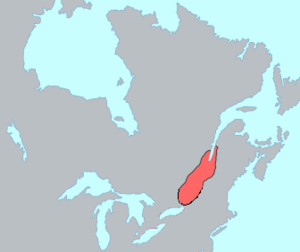

The St. Lawrence Iroquoians were an Indigenous group who lived from the 1300s until about 1580. They mostly lived along the St. Lawrence River in what is now Quebec and Ontario, Canada. They also lived in parts of New York and northern Vermont in the United States. They spoke Laurentian languages, which are part of the larger Iroquoian language family.

At one point, some experts thought there were as many as 120,000 St. Lawrence Iroquoians across a huge area. However, more recent studies, based on archaeological findings, suggest their total population was closer to 8,000–10,000 people. The largest known village had about 1,000 residents. It's believed they disappeared due to wars in the late 1500s, especially with the Mohawk nation of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois League). The Mohawk likely wanted to control trade with Europeans in the St. Lawrence Valley.

What we know about the St. Lawrence Iroquoians comes from several sources. These include stories passed down by current Indigenous peoples, the writings of French explorer Jacques Cartier, and studies by anthropologists and other experts. Since the 1950s, archaeological digs and language studies have added a lot to our understanding.

Archaeological evidence shows that the St. Lawrence Iroquoians were different from other Iroquoian groups in the region, like the Five Nations of the Haudenosaunee and the Wendat (Huron). Recent discoveries even suggest there might have been several distinct groups within the St. Lawrence Iroquoians themselves. The name "St. Lawrence Iroquoians" refers to people in a specific area who shared some cultural traits and a common language, but they were not a single political group.

The name of Canada itself likely comes from the Iroquoian word kanata, which means "village" or "settlement."

Contents

Who Were the St. Lawrence Iroquoians?

For many years, historians and archaeologists debated who the Iroquoian people in the St. Lawrence Valley were. These were the people Jacques Cartier met in 1535–36 at the villages of Stadacona and Hochelaga.

Since the 1950s, a lot of archaeological evidence has been found. This evidence, along with language studies, has helped experts agree that the St. Lawrence Iroquoians were a distinct group. They were not the direct ancestors or close relatives of the Iroquois Confederacy or the Huron people, who were met by later explorers like Samuel de Champlain.

By the 1990s, experts concluded that there might have been as many as 25 different tribes among the St. Lawrence Iroquoians. Their total population was estimated to be between 8,000 and 10,000 people. They lived in the lowlands along the river and east of the Great Lakes, including parts of present-day northern New York and Vermont.

Before these discoveries, some scholars thought these people were early Huron or Mohawk. However, archaeological findings and language studies have shown this is not true. For example, extensive archaeological work has proven that the homelands of the Mohawk, Onondaga, and Oneida tribes were not in the St. Lawrence Valley.

The St. Lawrence Iroquoians shared many cultural and linguistic traits with other Iroquoian groups. For instance, their Laurentian languages were part of the Iroquoian family, and their culture and society were similar in many ways.

The St. Lawrence Iroquoians seem to have disappeared from the St. Lawrence Valley before 1580. When Champlain arrived in 1608, he found no evidence of Native settlements there. By then, the Haudenosaunee used the valley mainly for hunting and as a path for war parties. Understanding who the St. Lawrence Iroquoians were helps us understand how Europeans and Indigenous peoples interacted in this region long ago.

Daily Life and Culture

The earliest signs of Iroquoian culture and maize (corn) farming in Canada date back to about 500 CE. By 1250 or 1300, corn was being grown in the area that is now Quebec City. Around 1300, there were four main areas where St. Lawrence Iroquoian culture thrived. These included areas in Jefferson County, New York, Grenville County, Ontario, the Lake St. Francis basin near Montreal, and the Montreal and Quebec City areas. There were also settlements in northern Vermont and nearby Ontario.

Most St. Lawrence Iroquoian villages were located a few kilometers inland from the river. By the late 1400s, these villages were surrounded by earthworks and palisades (strong fences made of logs). This shows they needed protection, likely from attacks. The villages typically covered an area of about 2 to 3.25 hectares (5 to 8 acres).

Inside the palisades, the St. Lawrence people lived in longhouses, just like other Iroquoian groups. These longhouses were long buildings, from 18 to 41 metres (60 to 135 foots) in length, and each housed several families. Archaeologists believe that most villages had 150-250 people, though some larger ones had many more.

The Iroquoians would live in a village for about ten years or more. After this time, their longhouses would start to fall apart, and the soil for their crops would become less fertile. Then, they would build a new village and clear land for new crops, usually just a few miles from their old home. This frequent moving makes it hard for archaeologists to figure out how many St. Lawrence Iroquoians there were at any one time.

The St. Lawrence Iroquoians had a mixed economy. They grew maize (corn), squash, and beans. They also hunted, fished, and gathered wild foods. These groups also had a matrilineal social system, meaning family lines were traced through the mother. Their political system was organized enough to allow them to form alliances at times. Most of them engaged in guerrilla warfare, grew and used tobacco, and made pottery. They also grew sunflowers for their oily seeds. Studies of old settlements show that corn and fish were their most important foods. They also hunted white-tailed deer and other animals.

In 1535, Jacques Cartier noticed differences between the people of Hochelaga (near Montreal) and Stadacona (near Quebec City). Cartier said Hochelaga had large, productive corn fields, and its people stayed in one place. In contrast, the people of Stadacona moved around more. The Stadaconans lived closer to the ocean and its resources, like fish, seals, and whales. They traveled widely in their birch bark canoes to find marine animals. The Quebec area was also the northernmost place in North America where farming was practiced, especially during the cooler temperatures of the Little Ice Age in the 1500s. For the Stadaconans, relying on farming was riskier, so they probably depended more on sea animals, fishing, and hunting.

The St. Lawrence Iroquoians were not politically united. Different villages and cultural groups might have been unfriendly or competitive with each other. They were also sometimes hostile towards neighboring Algonquian peoples and other Iroquoian groups.

Meeting Europeans

Breton, Basque, and English fishermen might have met the St. Lawrence Iroquoians early in the 1500s. French navigator Thomas Aubert visited the area in 1508. He sailed far into the Gulf of St. Lawrence and the St. Lawrence River. He took seven Native people back to France, who were possibly Iroquoians.

Jacques Cartier was the first European known for sure to have met the St. Lawrence Iroquoians. In July 1534, during his first trip to the Americas, Cartier met over 200 Iroquoians. They were men, women, and children camped on the north shore of Gaspé Bay in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. They had traveled in 40 canoes to Gaspé to fish for Atlantic mackerel, which were plentiful there. They were more than 600 kilometres (370 miles) from their home of Stadacona, which is now Quebec City. The Stadaconans met the French "very familiarly," which probably means they had traded with Europeans before.

On his next trip in 1535 and 1536, Cartier visited several Iroquoian villages. These included Stadacona (near present-day Quebec City) and Hochelaga (near modern-day Montreal). In the 20th century, archaeologists found similar villages further southwest, near the eastern end of Lake Ontario. They are still finding evidence of other distinct groups of St. Lawrence Iroquoians.

Around the time Jacques Cartier met them, Basque whalers began visiting the area every year. They had friendly trade relations with the St. Lawrence Iroquoians and other Native peoples. The Basques called them Canaleses, which probably came from the Iroquoian word "kanata" (village or settlement). The Basques and Native Americans in the Labrador-St. Lawrence area even developed a simplified language to understand each other.

What Happened to Them?

By the time explorer Samuel de Champlain arrived and founded Quebec in 1608, he found no trace of the St. Lawrence Iroquoians. The settlements Cartier had visited about 75 years earlier were gone. Historians and other experts have several ideas about why they disappeared:

- Wars: They might have been overwhelmed by wars with neighboring Iroquois tribes to the south, especially the Mohawk, or with the Hurons to the west. The Mohawk, located in eastern and central New York, had a strong reason to fight. They wanted to control the valuable fur trade routes along the St. Lawrence River. French trading was based at Tadoussac, further downstream, which was in the territory of the Innu. Champlain reported that the Algonquian peoples feared the powerful Iroquois.

- Diseases: They might have been hit hard by epidemics of diseases brought by Europeans, to which they had no immunity.

- Migration: They might have moved westward towards the shores of the Great Lakes.

Archaeological evidence and the historical context of the time suggest that wars with neighboring Iroquois tribes, especially the Mohawk, were the most likely reason for their disappearance. Because nothing remained of their settlements, it seems the St. Lawrence Iroquoians were overcome by other groups. Some survivors may have joined the neighboring Mohawk and Algonquin tribes, either by force or by agreement.

When Champlain arrived, both the Algonquins and Mohawks were using the St. Lawrence Valley for hunting and as a route for war parties. Neither group had permanent settlements upriver above Tadoussac, which had been an important trading post for years.

Language

Language studies show that the St. Lawrence Iroquoians likely spoke several different dialects of their language, often called Laurentian. This language is part of the larger Iroquoian language family, which also includes Mohawk, Huron-Wyandot, and Cherokee. Jacques Cartier made some notes about their language during his 1535-1536 voyage. He put together two lists with about 200 words. The St. Lawrence Iroquoians might have spoken two or more distinct languages across their territory, which stretched over 600 kilometres (370 miles) from Lake Ontario to east of Île d'Orléans.

Legacy and Honours

Extensive archaeological work in Montreal has uncovered 1,000 years of human history at the site. In 1992, a new museum, Pointe-à-Callière (Montreal Museum of Archaeology and History), opened there. It helps preserve the archaeological findings and shares new understandings about the city and the St. Lawrence Iroquoians.

Several major exhibits have showcased the growing knowledge about the St. Lawrence Iroquoians:

- 1992, Wrapped in the Colours of the Earth: Cultural Heritage of the First Nations, McCord Museum, Montreal, Quebec

- 2006-2007, The Saint Lawrence Iroquoians: Corn People, Pointe à Callière, Montreal Museum of Archaeology and History, Montreal, Quebec. (A book with the same name was published for this exhibition.)

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |