History of Basque whaling facts for kids

The Basques were amazing sailors and hunters from a region between France and Spain. They were among the first people to start hunting whales for business, not just for their own needs. For 500 years, they were the best at it! They traveled all over the North Atlantic Ocean and even reached the South Atlantic.

A French explorer named Samuel de Champlain said the Basques were "the cleverest men at this fishing" when he wrote about their whaling in Newfoundland. By the early 1600s, other countries wanted to learn from them. The English explorer Jonas Poole even said the Basques "were then the only people who understand whaling."

Soon, other nations learned the Basques' skills. They started their own whaling industries, sometimes pushing the Basques out. Basque whaling was strongest in the late 1500s and early 1600s. But it slowly declined by the 1700s. By the 1800s, it almost disappeared because too many right whales and bowhead whales had been caught.

Contents

Whaling in the Bay of Biscay

How Basque Whaling Started

Some old papers suggest the Basques were involved in whaling as early as the year 670. A document from that time talks about sending 40 barrels of whale oil from Bayonne to a faraway church. This oil was used for lighting lamps. This shows that Basque whaling was likely well-known even then.

Growing the Whaling Business

Another record from 1059 mentions whale meat being sold in Bayonne. By 1150, whaling had spread to other Basque areas in Spain. King Sancho the Wise gave special rights to the city of San Sebastián. These rights mentioned that baleen (whalebone plates) was an important product.

Whaling continued to spread along the coast. By 1190, it reached Santander. More cities like Hondarribia, Mutriku, and Getaria also gained special whaling rights. A document from 1237 for Zarautz said the King should get a slice of each whale caught. Whaling eventually reached Asturias (1232) and Galicia (1371).

About 49 ports along the coast had whaling businesses. The main whale they hunted was the North Atlantic right whale. They called it "sarde." They caught these whales during their migration, from October to March. They might have also hunted the gray whale, which used to live in the North Atlantic. Sometimes, they even caught a sperm whale.

Hunting Whales in the Bay of Biscay

Basque whalers used special stone watchtowers called vigías to spot whales. These towers were on high points overlooking the harbor. When a watchman saw a whale's spout, he would alert the hunters. He might burn straw, beat a drum, ring a bell, or wave a flag.

Once alerted, the men launched small rowing boats. They would strike the whale with a two-pronged harpoon and then use lances to kill it. A larger boat with ten men would then tow the whale's body to shore. At high tide, they would pull the whale onto the beach. There, they would cut off its blubber (fat). The blubber was then taken to a boiling house to be turned into oil.

Whaling and Local Culture

Whaling became so important in the Basque region that many towns put whales or whaling scenes on their official seals and coat-of-arms. Towns like Bermeo, Hondarribia, Getaria, and Biarritz showed their connection to whaling.

Laws were even passed to protect Basque whalers. In 1521 and 1530, foreign whalers were not allowed to operate off the Spanish coast. Later, in 1619 and 1649, foreign whale products could not be sold in Spanish markets.

Peak and Decline of Whaling

Whaling in the French Basque region was not as big as in the Spanish areas. It peaked in the late 1200s and then slowly declined. By 1567, commercial whaling had mostly ended there.

For the Spanish Basque region, whaling was strongest in the late 1500s. But it started to decline by the end of that century. In the early 1600s, whaling increased in Cantabria, Asturias, and Galicia. Basques would rent "land factories" (whaling stations) from the local people in Galicia. But this peak didn't last long.

By the late 1600s, whaling in these areas was generally declining. The War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1714) was the final blow. Whaling stopped completely in Cantabria (1720), Asturias (1722), and Galicia (1720). It barely survived in the Spanish Basque region.

Whale Catches in the Bay of Biscay

We don't know the exact number of whales caught by the Basques in the Bay of Biscay. Records from Lekeitio between 1517 and 1662 show 68 whales caught. That's about two or three whales a year. In 1536 and 1538, they caught six whales each year.

Whaling was a team effort among all the fishermen in a town. Only the watchmen were paid when no whales were caught. Catching just one whale could bring huge profits because whale products were very valuable. So, even catching one whale every two or three years could keep the business going.

It's hard to know how many whales were caught along the whole coast each year. Not all 49 whaling ports were active at the same time. Some only hunted whales for a short period. Experts think the total yearly catch might have been "some dozens, possibly reaching one hundred or thereabouts."

The End of Whaling in the Bay of Biscay

Only four whales were caught in the Bay of Biscay in the 1800s.

- The first was caught near Hondarribia in 1805.

- The second near San Sebastian in 1854.

- The third near Getaria-Zarautz in 1878.

- The last near San Sebastian in 1893.

In January 1854, three whales (a mother and her two calves) entered San Sebastian bay. Only one calf was caught. The whale caught in 1878 caused a lawsuit between Getaria and Zarautz. The whale was left to rot on the shore and had to be blown up because of the smell!

On May 14, 1901, fishermen killed a 12-meter (39-foot) right whale near Orio using dynamite. This event is remembered in a famous folk poem. A local festival is held every five years to celebrate this catch. After that, only a few more right whales were seen in the area. The last sighting was in 1977.

Basque Whaling in Newfoundland and Labrador

Early Claims of Discovery

Around 1525, Basques started whaling and fishing for cod near Newfoundland and Labrador. Some old historians claimed that Basques, Bretons, and Normans were the first Europeans to reach the New World, even before Christopher Columbus. They said French Basques discovered North America while chasing whales across the North Atlantic Ocean.

Starting and Expanding in the New World

The first clear evidence of Basque whaling in the New World dates back to the early 1500s. French Basques, following cod fishermen, found rich whaling areas in Terranova (Newfoundland). The Basques called their main whaling area Grandbaya, which is now known as the Strait of Belle Isle.

At first, their trips were for both cod fishing and whaling. Instead of whale oil, they brought back salted whale meat. The ship La Catherine d'Urtubie made a known voyage in 1530, returning with dried cod and twelve barrels of whale meat.

Later, expeditions focused only on whale oil. The first places to process whale oil in southern Labrador might have been built in the late 1530s. By the 1540s, Spanish Basques also started sending whaling trips to Newfoundland. These trips were very successful financially. They delivered large amounts of whale oil to cities like Bristol, London, and Flanders.

Whale oil, called "lumera," was used for lighting. "Sain" or "grasa de ballena" was mixed with tar to seal ships. It was also used in the textile industry. Ambroise Paré, a famous surgeon, said in 1564 that baleen was used to make farthingales (hoops for skirts), knife handles, and other items.

Most records about whaling in Newfoundland are from 1548 to 1588. Many of these mention Red Bay. This area was important for Basque whalers. They sometimes spent winters there. In 1584, the first known Canadian will was written there for a dying Basque whaler. The last time Basques spent winter in Red Bay was in 1603. While there, the whalers even developed a special language with local native people.

Shipwrecks in Red Bay

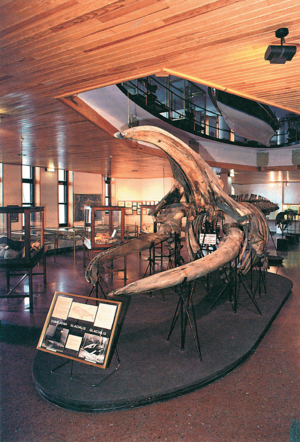

In 1978, the wreck of a ship was found in Red Bay. It is believed to be the Spanish Basque galleon San Juan. This large ship was lost in 1565 during an autumn storm. It was carrying almost 1,000 barrels of whale oil. The ship sank near shore, but the crew saved some sails, equipment, and about half the oil. The captain and crew got a ride back to Spain. The next year, they salvaged more from the wreck before it completely disappeared.

Three more shipwrecks have been found in Red Bay, the latest in 2004. One ship, found in 1983, seemed to have sunk because of a fire.

Hunting Methods and Life in Labrador

Basques hunted two types of whales in southern Labrador: the North Atlantic right whale and the bowhead whale. Right whales were caught in the summer. Bowhead whales were caught from fall to early winter. Later studies of old whale bones showed that right whales became very rare.

During the busiest time (1560s–1580s), Spanish Basques used large, armed galleons. French Basques used smaller ships. A large Basque ship with over 100 men needed a lot of food and drink for the two-month journey. In Labrador, the men ate mostly local cod and salmon, along with some caribou or wild duck. They also had dried peas, beans, and other supplies.

Before leaving for Terranova in May or June, a priest would bless the ships. The journey across the stormy North Atlantic was very difficult. After two months, the ships would anchor in one of the twelve harbors in Labrador.

Once the ice melted, the ships entered the harbors. Coopers (barrel makers) went ashore to build their homes and workshops. Most of the crew stayed on the ship. Boys went ashore to chop wood and prepare meals.

The men built temporary whaling stations on shore to process whale blubber into oil. These stations had large fireboxes made of stone, where they would boil the blubber in big pots. The foundations of these boiling houses were made of clay and had roofs of red ceramic tiles.

Near the boiling houses, there was a cooperage, a building where barrels were made. The cooper lived comfortably there. Other crew members slept in smaller shelters made of wood and cloth. Many of these shelters have been found on Saddle Island.

In 1982, archaeologists found a whaler's cemetery on Saddle Island. Over 60 graves were found, containing more than 140 bodies. Most were adult men in their 20s to 40s, but two were twelve-year-old boys. Some burials included well-preserved wool clothing, showing how they dressed for the cold weather.

At least sixteen whaling stations have been found in Red Bay. During the peak of whaling, almost 1,000 men worked in and around Red Bay. As many as eleven ships visited the harbor in 1575 alone. Watchtowers (vigías) were also built on Saddle Island to spot whales.

When an 8-meter (26-foot) whale was seen, small boats called chalupas were sent out. Each boat had a steersman, five rowers, and a harpooner. They would harpoon the whale and attach a wooden drag to tire it out. Once tired, they would kill it with lances. If it got dark, those ashore would light signal fires to guide the boats back.

The whales were brought to a cutting stage near the shore. There, the blubber was cut off and boiled into oil. The oil was then poured into large oak barrels, each holding 55 gallons. These barrels were towed to the ship and stored in the hold. When a ship was full, it sailed back to Pasaia in Spain to unload its cargo. Pasaia was a favorite port because it had a deep entrance and was safe from storms.

Peak and Decline in Newfoundland

Whaling in Terranova became very busy after a peace treaty in 1572. On average, fifteen ships went to Terranova each year, and sometimes twenty during the busiest times. Some sources even claimed over 200 ships, but this was likely an exaggeration.

Ships from Red Bay alone sent 6,000–9,000 barrels of oil to Europe every year during the peak. Other harbors produced thousands more. Each ship averaged 1,000 barrels per season. This cargo was as valuable as the treasure brought back by Spanish galleons from the Caribbean. So, at least 15,000 barrels of oil were produced each year, meaning about 300 whales were caught.

By the 1580s, whaling started to decline. Ships returned with less oil. This was also when the king of Spain needed Basque ships for his navies, especially for the Spanish Armada against England in 1588. This stopped many Spanish Basque whaling trips.

Other problems also led to the decline:

- Attacks by local Inuit people, which caused some deaths.

- Raids by English and Dutch pirates.

- The opening of new whaling grounds in Spitsbergen.

By 1632, Basques found it safer to hunt whales in other areas like Mingan and Tadoussac. Despite this, Spanish Basque expeditions continued to Labrador until the late 1600s. The end came in 1697 when Spanish Basques were stopped from sending whaling trips to Terranova. The Treaty of Utrecht (1713) finally removed them from the Gulf of St. Lawrence. French Basques continued to send whaling expeditions to Terranova for a while longer.

Whaling in Brazil and Iceland

Brazil and Early European Whaling

By the early 1600s, Basque whaling reached Brazil. This happened because the local government needed whale oil for its growing sugar industry. They didn't know how to hunt whales, so they asked for help. In 1602, two Basque whalers went to Brazil. Their crews taught the Brazilians how to hunt humpback whales and southern right whales.

For almost ten years, Basque ships traveled from Spain to Brazil. The oil they produced fueled sugar mills and was used for lubricating machines and sealing boats. This ended in 1610 when a Basque captain tried to smuggle wood out of the country. He and his men were arrested. The same year, the king declared that whaling was a royal monopoly.

Whaling in Iceland

The first clear mention of Basque whaling in Iceland is from the early 1600s. Icelandic records say Basque whalers were active around the Westfjords in 1610. Another record says three Basque ships were whaling there in 1608. In 1613, a Spanish Basque ship caught seventeen whales in Steingrímsfjörður.

Basque whaling in Iceland continued until the early 1700s. However, by the late 1600s, Icelandic records mentioned French and Dutch whalers more often than Spanish Basques. In the late 1600s, French Basque ships from Saint-Jean-de-Luz and Ciboure hunted whales off Iceland. They often came after finishing whaling off Greenland. The last time whalers were mentioned ashore in Iceland was in 1712.

During this time, a simple language called Basque–Icelandic pidgin developed. This helped Basque whalers communicate with traders from different countries in the North Atlantic.

Whaling in Spitsbergen and Northern Norway

Spitsbergen and Expulsion

In the early 1600s, the Basques started to lose their near-monopoly on whaling in the northeastern North Atlantic Ocean. Their skilled whalers were hired by English, Dutch, French, and Danish expeditions to Spitsbergen. There, they hunted the bowhead whale.

In 1611, a Basque whaler from Saint-Jean-de-Luz caught the first whale there for an English expedition. When merchants in San Sebastian heard about this new whaling ground, they wanted to go too. In 1612, they sent a ship. They found so many whales that the sea was "obscured" (covered) for miles. The ship returned to Spain with exciting news.

This led to many other countries sending whaling fleets to Spitsbergen in 1613, including a dozen ships from San Sebastian and several from Saint-Jean-de-Luz. However, the English Muscovy Company claimed a monopoly on whaling in Spitsbergen. They seized the oil and equipment from Basque ships and sent them home. The Basques lost a lot of money.

Despite this, Basques tried to continue whaling in the area. In 1623 and 1625, Danish companies hired Basque ships to whale in Spitsbergen. In 1632, two French Basque ships sailed to a Danish station. They were told to leave by the Dutch. So, they sailed to North Cape, waited for the Dutch fleet to leave, and then plundered a Dutch station. They stole oil and baleen and sold it for a good profit.

Basques found it hard to establish themselves in Spitsbergen. In 1637, a French Basque ship was caught by a Danish warship and had its blubber and baleen seized.

Whaling in Northern Norway

In Finnmark (Northern Norway), the Basques faced similar problems from the Dano-Norwegian crown. They hunted the North Atlantic right whale there. In 1614, a Spanish Basque ship was forced to pay a fee to the local sheriff. The next year, several Basque ships went to Northern Norway. The Dano-Norwegian crown sent a navy expedition, confiscating oil and seizing ships. Basque whalers continued to be recorded in these waters into the 1620s. Some sources claim they were there as late as 1688–1690.

First Offshore Whaling and Later Arctic Trips

To avoid paying fees to northern countries, the Basques started using tryworks (boiling stations) on their ships in 1635. This meant they could catch and process whales offshore. This technique was risky, and ships sometimes caught fire.

For whaling in the northeastern North Atlantic, Spanish Basques used smaller ships than those used for Terranova. French Basques used strong frigates with cannons, as France and Holland were often at war. Many French Basque ships sailed to Le Havre or Honfleur in Normandy to sell their oil, as there was a large market there.

Poor catches in the 1680s and the Nine Years' War (1688–1697) caused a big decline in French Basque whaling. By the early 1700s, only one or two ships were left.

After the War of Spanish Succession, French Basque whaling started to recover. They had to hire Spanish Basques because there weren't enough experienced sailors. In 1721, about twenty Basque ships were among the foreign whalers in the Davis Strait. By 1730, more than 30 whalers were sent out each year, marking a "new period of prosperity." But this was followed by a quick decline. The last Basque whaling expeditions were sent before the Seven Years' War (1756–1763). Attempts to restart the trade after that were not successful.

|

See also

In Spanish: Balleneros vascos para niños

In Spanish: Balleneros vascos para niños

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |