Basque–Icelandic pidgin facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Basque–Icelandic pidgin |

|

|---|---|

| Region | Iceland, Atlantic |

| Era | 17th century |

| Language family | |

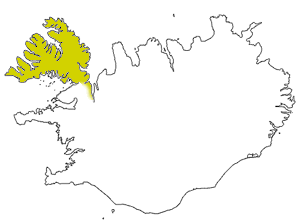

Westfjords, the Icelandic region that produced the manuscript containing the Basque–Icelandic pidgin

|

|

The Basque–Icelandic pidgin was a special mix of languages. It was based on the Basque language. People spoke it in Iceland during the 1600s. This pidgin used words from Basque, Germanic languages, and Romance languages.

A pidgin is a simplified way of speaking. It helps people who speak different languages talk to each other. Basque whale hunters traveled to the Westfjords area of Iceland. They used this pidgin to communicate with the local people.

This pidgin might have started in the Westfjords. This is where old papers with the language were found. But it also had words from many other European languages. So, it might have been created somewhere else. Basque sailors could have brought it to Iceland.

The pidgin mixed Basque words with words from Dutch, English, French, German, and Spanish. It was not a mix of Basque and Icelandic. Instead, it was a mix of Basque and other languages. It got its name because it was written down in Iceland. It was also translated into Icelandic.

Only a few old papers have been found that contain this pidgin. These papers are like small dictionaries. Because of this, we do not know much about the language.

Contents

Basque Whalers in Iceland

Basque whalers were among the first to hunt whales for business. They sailed all over the North Atlantic Ocean. They even reached places like Brazil. They started coming to Iceland around the year 1600.

In 1615, a sad event happened. Some Basque sailors were shipwrecked. They got into a conflict with the local people. This led to an event known as the Slaying of the Spaniards. Many Basque sailors lost their lives.

Basques continued to sail to Iceland after this. But in the second half of the 1600s, French and Spanish whalers visited Iceland more often.

Discovering the Old Glossaries

Only a few anonymous glossaries have been found. A glossary is like a small dictionary. Two of these were found among the papers of a scholar named Jón Ólafsson of Grunnavík. He lived in the 1700s. The glossaries were called:

- Vocabula Gallica ("French words"). This one was written in the late 1600s. It had 16 pages with 517 words and short sentences. It also had 46 numbers.

- Vocabula Biscaica ("Biscayan (Basque) words"). This was a copy made by Jón Ólafsson in the 1700s. The original paper is now lost. It had 229 words and short sentences. It also had 49 numbers. This glossary contains many pidgin words and phrases.

An Icelandic language expert, Jón Helgason, found these papers in the 1920s. He found them at the University of Copenhagen. He copied the glossaries. Then he translated the Icelandic words into German. He sent the copies to a professor named C.C. Uhlenbeck.

Professor Uhlenbeck knew a lot about Basque. He gave the glossaries to his student, Nicolaas Gerard Hendrik Deen. In 1937, Deen published his important study on the glossaries. It was called Glossaria duo vasco-islandica.

In 1986, Jón Ólafsson's original papers were brought back to Iceland from Denmark.

The manuscript with the glossaries (University of Iceland):

There is also a mention of a third glossary. An Icelandic linguist, Sveinbjörn Egilsson, wrote a letter. He talked about a document with "funny words and glosses." He copied eleven examples from it. This glossary is now lost. But his letter is still kept at the National Library of Iceland.

The Fourth Glossary

A fourth Basque–Icelandic glossary was found later. It was at the Houghton Library at Harvard University. A German historian, Konrad von Maurer, had collected it in 1858. This paper is from the late 1700s or early 1800s.

The glossary was discovered around 2008. The person who owned it before did not know it had Basque text. Only two pages have the Basque–Icelandic glossary. The other pages have unrelated things. These include instructions about magic spells.

It seems the person who copied it did not know it was Basque. The text had a heading that said "A few Latin glosses." Many words in this copy are wrong or hard to read. This suggests the copyist was not used to writing such words.

Many words in this glossary are not in Deen's earlier glossary. So, people think it is a copy of another unknown Basque–Icelandic glossary. About 68 words and phrases could be understood from it.

Examples of Pidgin Phrases

Many words in the pidgin came from Basque:

- atorra, meaning 'shirt'

- balia, meaning 'baleen whale'

- berria, meaning 'new'

- berrua, meaning 'warm'

- biskusa, a word for 'biscuit'

- bustana, meaning 'tail'

- eta, meaning 'and'

- galsardia, meaning 'the sock'

- gissuna, meaning 'the man'

- locaria, meaning 'the tie/lace(s)'

- sagarduna, meaning 'the cider'

- ser, meaning 'what'

- sumbatt, meaning 'how many'

- travala, meaning 'to work'

- usnia, meaning 'the milk'

- bura, meaning 'butter'

Some words came from Germanic languages:

- cavinit, meaning 'nothing at all'

- for in a sentence like sumbatt galsardia for

- for mi, meaning 'for me' (or 'I')

- for ju, meaning 'for you'

And others came from Romance languages:

- cammisola, meaning 'shirt'

- mala, meaning 'bad' or 'evil'

- trucka, meaning 'to exchange'

In the pidgin, most nouns and adjectives ended with -a. This is like the Basque definite article. But sometimes, it was used even when it would be wrong in real Basque. Also, the order of nouns and adjectives was often switched. For example, berrua usnia means 'warm milk'. In proper Basque, it would be esne beroa ('milk warm').

The glossaries have many Spanish and French words. This does not mean the pidgin was a mix of those languages. It shows that Basque itself has borrowed many words from its neighbors over time. Also, many Basque sailors might have spoken French or Spanish too. This would help explain why some words appear in the glossaries.

More Examples

These examples are from the Harvard manuscript that was found recently:

| Basque pidgin | Correct Basque | Icelandic | English meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nola dai fussu | Nola deitzen zara zu? | hvad heitir þu | What's your name? |

| Jndasu edam | Indazu eda-te-ra | gief mier ad drecka | Give me (something) to drink |

| Jndasu jaterra | Indazu ja-te-ra | gief mier ad eta | Give me (something) to eat |

| Jndasunirj | Indazu niri | syndu mier | Show me |

| Huna Temin | Hunat jin | kom þu hingad | Come here |

| Balja | Balea | hvalur | A whale |

| Chatucumia | katakume | kietlingur | A kitten |

| Bai | Bai | ja | Yes |

| Es | Ez | nei | No |

The phrase nola dai fussu means "What's your name?". It is a simpler way of saying the correct Basque sentence.

See also

In Spanish: Pidgin vasco-islandés para niños

In Spanish: Pidgin vasco-islandés para niños

- Algonquian–Basque pidgin, another pidgin based on Basque, found in Canada

- Russenorsk, a pidgin that mixed Russian and Norwegian

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |