Coureur de bois facts for kids

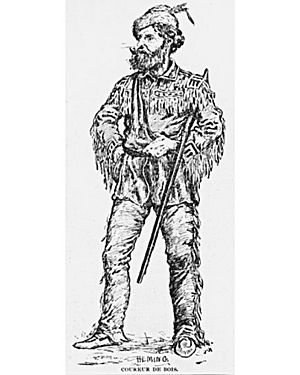

A coureur des bois (which means "runner of the woods" in French) was an independent French-Canadian trader. These brave adventurers traveled deep into New France and other parts of North America. Their main goal was to trade European goods like tools and blankets for furs, especially beaver pelts, with First Nations peoples. Many coureurs des bois learned the languages and customs of the Indigenous groups they met.

These journeys were a big part of starting the North American fur trade. At first, they traded for beaver coats and furs. As the demand for furs grew in Europe, coureurs des bois hunted and traded for the best beaver skins. These skins were then sent to Europe to be made into felt for hats and other items.

Contents

How the Coureurs des Bois Changed Over Time

French settlers had traded with Indigenous people since New France began. But the coureurs des bois became most important in the second half of the 1600s. After 1681, a new system started. Independent coureurs des bois were slowly replaced by voyageurs. These voyageurs were workers hired by licensed fur traders. They traveled widely by canoe, often for big companies. By the early 1700s, the coureurs des bois were less important in the fur trade. Still, they became a lasting symbol of New France.

Early Explorers and Interpreters (1610–1630)

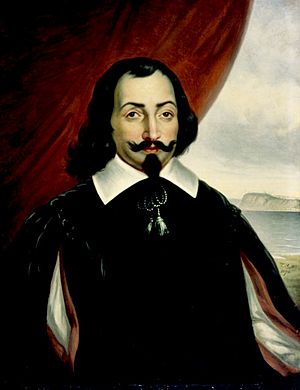

After starting a settlement in Quebec City in 1608, Samuel de Champlain wanted to make friends with the local First Nations. He sent young French boys to live with them. The goal was for these boys to learn Indigenous languages. This way, they could become interpreters and help convince the First Nations to trade with the French. The Dutch were also trading along the Hudson River, so competition was high.

The French boys learned native languages, customs, and survival skills. They often adapted quickly to their new homes. For example, when Champlain visited Étienne Brûlé in 1611, he was surprised. Brûlé had been living with a Huron tribe for a year. He was dressed in native clothing and spoke the Huron language fluently.

These early explorers, like Brûlé, taught the French colonists about the complex trading networks of the native peoples. They served as interpreters and helped the fur trade grow. Between 1610 and 1629, many Frenchmen spent months living among the First Nations. Over time, these explorers became more involved in the fur trade. This paved the way for the coureurs des bois to truly emerge in the mid-1600s.

The Rise of the Coureurs des Bois (1649–1681)

The term "coureur des bois" mostly refers to those who traded furs outside the usual rules. Early in the fur trade, this term was used for men who went deep into the wilderness to trade. This was often done without official permission.

The government of New France usually wanted First Nations to bring furs directly to French merchants. They didn't want French settlers to go far from the St. Lawrence River valley. By the mid-1600s, Montreal became the main fur trade center. A yearly fair was held there in August. First Nations exchanged their furs for European goods. While coureurs des bois always existed, French officials often tried to stop them.

In 1649, the new governor, Louis d'Ailleboust de Coulonge, allowed Frenchmen who knew the wilderness to visit Huron Country. They were to encourage Hurons to come to Montreal for trade. This didn't officially allow coureurs des bois to trade on their own. However, some historians see this as the start of the coureurs des bois as a distinct group.

Several things led to a sudden increase in coureurs des bois in the 1660s:

- More People: The population of New France grew a lot in the late 1600s. Many new immigrants, including former soldiers and young people, arrived. Many of them chose the free life of a coureur des bois.

- Peace with Iroquois: Peaceful relations with the Iroquois in 1667 made traveling into Canada's interior much safer.

- Less Strict Rules: The companies that controlled the fur trade went bankrupt. The new company, the Compagnie des Indes occidentales, was less strict. This allowed more independent traders.

- Falling Fur Prices: The price of beaver furs in Europe dropped in 1664. This made more traders go to the "pays d'en haut" (upper country, around the Great Lakes) to find cheaper furs.

So, in the mid-1660s, becoming a coureur des bois became easier and more profitable. This sudden growth worried many colonial officials. In 1680, one official, Duchesneau, guessed there were 800 coureurs des bois. This was about 40% of the adult male population! But these reports were greatly exaggerated. Even at their peak, coureurs des bois were a very small part of New France's population.

The Decline of the Coureurs des Bois (1681–1715)

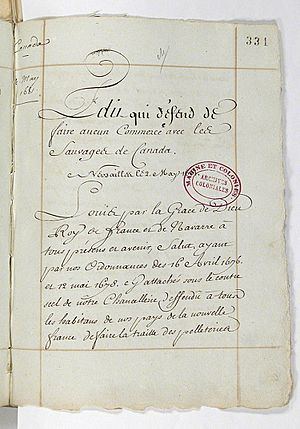

In 1681, to control the independent traders and their growing profits, the French government created a system of licenses called congés. This system gave out 25 licenses each year to merchants traveling inland. The people who received these licenses became known as "voyageurs." They used canoes to transport fur trade goods and bring back pelts for a licensed trader or company.

The congé system created the voyageur, who was a legal and respected counterpart to the coureur des bois. With voyageurs, the fur trade became more organized, like a modern business. It involved single ownership and hired workers. From 1681 onwards, voyageurs began to take over from the coureurs des bois. However, some coureurs des bois continued to trade without licenses for several more decades. After the congé system started, the number of coureurs des bois and their influence in the colony slowly decreased.

Life as a Coureur des Bois

Important Skills

A successful coureur des bois needed many skills. They had to be good at business and expert canoe paddlers. To survive in the Canadian wilderness, they also needed to be good at fishing, snowshoeing, and hunting. One Jesuit priest described them as people who didn't mind traveling "five to six hundred leagues by canoe, paddle in hand." They could live "off corn and bear fat for twelve to eighteen months" and sleep "in bark or branch cabins."

Life as a coureur des bois was physically very hard. But the hope of making money motivated many. The promise of adventure and freedom also convinced others to join this life.

Long-Distance Fur Trade and Canoe Travel

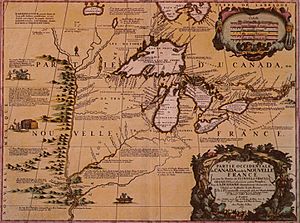

Because there were no roads, transporting heavy goods and furs depended on canoes. Early travel was dangerous, and coureurs des bois, who traded in unknown areas, faced high risks. They usually left Montreal in the spring, as soon as the rivers and lakes were free of ice, usually in May. Their canoes were full of supplies and goods for trading.

The route west to the best beaver lands often followed the Ottawa River and Mattawa River. This route required many portages, where they had to carry their canoes and goods over land. Another route went along the upper St. Lawrence River and the Great Lakes, passing by Detroit on the way to Michilimackinac or Green Bay. This route had fewer portages but was more exposed to Iroquois attacks during times of war. The powerful Iroquois nations controlled territory along the Great Lakes and wanted to protect their hunting grounds.

These trading trips often lasted for months and covered thousands of kilometers. Coureurs des bois sometimes paddled twelve hours a day. Packing a canoe for such a trip was difficult. More than thirty items were considered essential for a coureur des bois to survive and do business. They could trade for food, hunt, and fish. But trade goods like "broadcloth, linen and wool blankets, ammunition, metal goods (knives, hatchets, kettles), firearms, liquor, gunpowder and sometimes even finished clothing, took up the majority of space in the canoe." Food for the journey needed to be light, practical, and non-perishable.

Relationships with First Nations

The work of a coureur des bois required close contact with First Nations. Indigenous peoples were essential because they trapped the fur-bearing animals, especially beaver, and prepared the skins. Relations between coureurs and First Nations were not always peaceful, and sometimes could become violent. However, trade was much easier when the two groups stayed friendly.

Trade often included giving gifts to each other. Among the Algonquin and other groups, exchanging gifts was a common way to keep alliances strong. For example, Pierre-Esprit Radisson and his friends made good relationships with First Nations inland by giving them European goods as gifts.

Marriage "à la façon du pays" (following local custom) was common between native women and coureurs des bois, and later with voyageurs. These marriages benefited both sides. Indigenous women played a key role as translators, guides, and mediators. They became "women between" cultures. For example, Algonquin communities often had more women than men, possibly due to warfare. The remaining marriages among Algonquins were often polygamous, where one husband married two or more women.

French military commanders, who were often involved in the fur trade, saw these marriages as helpful. They improved relations between the French and the First Nations. Native leaders also encouraged such unions, especially when the couple formed lasting bonds. However, Jesuit priests and some high-ranking colonial officials disliked these relationships. French officials preferred coureurs des bois and voyageurs to settle near Quebec City and Montreal. They saw lasting relationships with native women as more proof that the coureurs des bois were lawless and wild.

Myths About the Coureurs des Bois

The role and importance of the coureurs des bois have often been exaggerated throughout history. This figure has become almost mythical, leading to many false stories. Sometimes, coureurs des bois are even confused with all "Canadiens" (Canadians).

The myth-making happened in a couple of ways. At first, people in France judged the colonies based on their own fears about the old ways of government. If order was hard to keep in Europe, it seemed impossible in the colonies. Stories of young men choosing a life where they would "do nothing" and be "restrained by nothing" fit into the French upper class's fears of people not following rules. So, coureurs des bois became a symbol of the colony for those back in France.

The idea of the coureurs des bois representing all Canadians was also spread by writers. These included the 18th-century Jesuit priest F-X. Charlevoix and the 19th-century American historian Francis Parkman. Their historical accounts are more like popular stories than strict academic history. Charlevoix was very influential because he was a trusted Jesuit priest who had traveled in Canada. But historians have criticized his "historical" work for being too "light" and for copying too much from other authors. Critics also note that Charlevoix mixed up different time periods. He didn't clearly separate voyageurs from coureurs des bois. This made the coureurs des bois seem more numerous and important than they really were. But Charlevoix's work was often quoted by others, which helped spread the myth of the Canadian as a coureur des bois.

Finally, "romans du terroir" (rural novels) also added to the myth. These novels featured coureurs des bois much more than their actual numbers or influence deserved. The coureurs des bois were shown as very strong, free-spirited, and wild characters. They were perfect heroes for the romantic novels of important 19th-century writers like Chateaubriand, Jules Verne, and Fenimore Cooper.

Famous Coureurs des Bois

Most coureurs des bois were mainly fur traders and not widely known. The most famous ones were also explorers.

- Étienne Brûlé: He was the first European to see the Great Lakes. He traveled to New France with Samuel de Champlain.

- Jean Nicolet: Born in France around 1598, he moved to New France in 1618. Samuel de Champlain asked him to live with an Algonquin group to learn their languages. Nicolet became an interpreter and was adopted by the First Nations. He even attended their councils and helped with treaties. He explored Green Bay in what is now Wisconsin.

- Médard Chouart des Groseilliers: Born in 1618, he was a French explorer and fur trader in Canada. He learned the skills of a coureur des bois. With his brother-in-law, Pierre-Esprit Radisson, he explored west into new territories looking for trade. They helped establish the Hudson's Bay Company.

- Pierre-Esprit Radisson: Born in 1636, he came to New France in 1651. He was captured by the Mohawks but adopted by them. This helped him learn native languages, which he used as an interpreter. He worked closely with his brother-in-law, Médard des Groseilliers, on many trade and exploration trips. They are credited with helping to create the Hudson's Bay Company.

- Daniel Greysolon, Sieur du Lhut: Born in 1639, he was a French soldier and explorer. He was the first European known to visit the area where Duluth, Minnesota, is now located. He also explored the headwaters of the Mississippi River.

- Pierre Gaultier de Varennes, sieur de La Vérendrye: Born in 1685, he was a key explorer and fur trader.

- Louis-Joseph Gaultier de La Vérendrye: Born in 1717, he and his three brothers were sons of Pierre de La Vérendrye. They continued their father's explorations.

- Martin Chartier: Born in 1655, he traveled with famous explorers Joliet and LaSalle. He later became an outlaw but continued to trade furs in Tennessee, Ohio, and Pennsylvania.

Coureurs des Bois in Stories and Movies

The idea of the coureur des bois has appeared in many stories, TV shows, and films:

- The 1910 operetta Naughty Marietta has a song called Tramp Tramp Tramp (Along the Highway) that mentions "Couriers de Bois."

- In James A. Michener's 1974 novel Centennial and the 1978 TV mini-series, a character named Pasquinel is a coureur des bois. He is an early mountain man and trapper in 1795 Colorado.

- A 1990 skit by the Canadian comedy group The Kids in the Hall called "Trappers" shows two trappers canoeing through office buildings. They trap businessmen in suits, making fun of this part of Canadian history.

- The 2015 film The Revenant shows a group of violent coureurs des bois in North Dakota. However, real coureurs des bois usually had good relationships with First Nations.

- The 2016 TV series Frontier is about the North American fur trade in the late 1700s. It features fictional coureurs des bois.

|

See also

In Spanish: Coureur des bois para niños

In Spanish: Coureur des bois para niños

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |