Martin Chartier facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Martin Chartier

|

|

|---|---|

Historical marker, erected in 1925, in Washington Boro, Pennsylvania, commemorating the life of Martin Chartier

|

|

| Born | 1655 |

| Died | 1718 (aged 62–63) |

| Nationality | French-Canadian |

| Occupation | Explorer, fur trader, glovemaker |

| Known for | Travels with Louis Jolliet and René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle |

| Spouse(s) | Sewatha Straight Tail (1660-1759) |

| Parent(s) | René Chartier (1621-1689); Madeleine Ranger (1621?-1662) |

| Relatives | Children: Mary Seaworth (Sewatha) Chartier (1687–1732); Peter Chartier (1690–1759) |

Martin Chartier (1655 – April 1718) was a French-Canadian explorer and trader. He was also a carpenter and glove maker. He spent much of his life living with the Shawnee Native Americans. This was in what is now the United States.

Chartier joined Louis Jolliet on two trips to the Illinois Territory. He also went with René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle on his 1679–80 journey. This trip explored Lake Erie, Lake Huron, and Lake Michigan. Chartier helped build Fort Miami and Fort Crèvecoeur. In April 1680, Chartier and six other men left Fort Crèvecoeur. They took supplies, damaged the fort, and left.

In a letter from 1682, La Salle said that Martin Chartier "was one of these who incited the others to do as they did." Chartier's name was sometimes spelled as Chartiere, Chartiers, Shartee, or Shortive.

Contents

Early Life and Family

Martin Chartier was born in 1655 in Poitiers, France. When he was twelve, his family moved from France to Quebec in 1667. His father René, brother Pierre, and sister Jeanne Renée went with him. They joined his grandfather and uncle who were already there.

On the boat trip to Canada, Chartier and his father met René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle. La Salle was also moving to Canada. Some stories say young Chartier learned to make gloves in Montreal. Other information suggests he was trained as a carpenter.

Chartier's father, uncle, and grandfather were killed in the Lachine massacre. This event happened near Montreal in August 1689.

Exploring with Louis Jolliet

In 1672, Martin Chartier and his brother Pierre joined Louis Jolliet's second expedition. In December 1672, they reached the Straits of Mackinac. There, Jolliet met with Pierre Marquette. They spoke with Native Americans and made maps. These maps were for a famous 1673 trip to find the mouth of the Mississippi River. They wanted to know if it flowed into the Gulf of Mexico or the Pacific Ocean.

In 1674, Chartier went with Louis Jolliet to the Illinois Territory. He met the Pekowi Shawnee people there. At that time, they lived near the Wabash River. After Jolliet went back to Quebec in 1675, Chartier returned to the area. He married Sewatha Straight Tail (1660-1759), who was the daughter of Shawnee chief Straight Tail Meaurroway Opessa. Their first child, a daughter, was born in 1676.

La Salle's 1679 Expedition

Chartier joined René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle on his 1679-1680 journey. They traveled to Lake Erie, Lake Huron, and Lake Michigan. Belgian missionary Louis Hennepin and French missionary Zenobius Membre also joined them.

Chartier helped build Le Griffon. This was a large sailing ship with seven cannons. It was built on the upper Niagara River. It was launched on August 7, 1679. It was the biggest sailing ship on the Great Lakes at that time. La Salle sailed Le Griffon across Lake Erie to Lake Huron. Then they went to Michilimackinac and on to present-day Green Bay, Wisconsin. Le Griffon left for Niagara with furs but was never seen again.

La Salle and his men continued in canoes. They went down the western shore of Lake Michigan. They rounded the southern end to the mouth of the St. Joseph River. Chartier helped build a fort there in November 1679. They called it Fort Miami (now St. Joseph, Michigan). They waited there for Henri de Tonti and his group. Tonti's group had walked across the Lower Peninsula of Michigan.

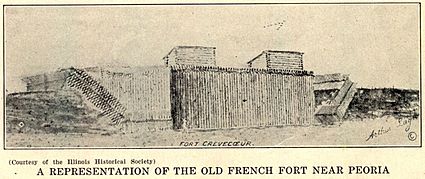

Tonti arrived on November 20. On December 3, everyone set off up the St. Joseph River. They followed it until they had to carry their canoes over land. This was at present-day South Bend, Indiana. They crossed to the Kankakee River and followed it to the Illinois River. There, they started building Fort Crèvecoeur on January 15, 1680. Father Hennepin went with a small group to find where the St. Joseph and Mississippi rivers met. He was captured by Sioux warriors and held for several months.

Leaving Fort Crèvecoeur

Chartier helped build Fort Crèvecoeur. It was built along the Illinois River near present-day Peoria, Illinois. This fort was the first building made by white men in what is now Illinois. It was also the first French fort in the West. La Salle also started building another ship to replace Le Griffon.

On March 1, 1680, La Salle left on foot for Fort Frontenac to get supplies. He left Henri de Tonti in charge of Fort Crèvecoeur. On his way back, La Salle thought Starved Rock would be a good place for another fort. He sent a message to Tonti about this idea. Tonti took five men and went to check out Starved Rock.

Soon after Tonti left, on April 16, 1680, seven men who stayed at Fort Crèvecoeur left the fort. They took supplies and ammunition. They threw other goods into the river and burned the fort down. In a letter from 1682, La Salle said Chartier was one of the main people who encouraged the others to leave.

The men likely left because they were afraid of attacks from Iroquois groups. The Iroquois were fighting the local Illinois communities during the Beaver Wars. The men wanted La Salle to return with them to Montreal, but he did not want to. Also, one of the men who was later caught said that some of them "had had no pay for three years." He also said La Salle had treated them badly.

At Fort St. Louis, two men told Tonti that the fort was destroyed. Tonti sent messages to La Salle in Canada to tell him what happened. Tonti then went back to Fort Crèvecoeur to get any tools that were not destroyed. He moved them to the Kaskaskia Village at Starved Rock. Later, La Salle caught some of the men who left on Lake Ontario. But Chartier was not among them. He went along the south shore of Lake Ontario towards upstate New York. He was part of a second group of eight men who left. Chartier said in 1692 that he went to Esopus, New York. He may have meant he found safety among the Esopus people, who lived along the Hudson River. Louis-Henri de Baugy, Chevalier de Baugy later said that Chartier might have stayed with Shawnees near Starved Rock for a year or two. Then he returned to Montreal.

Life with the Shawnee People

After leaving Fort Crèvecoeur, Chartier was considered an outlaw. But he seems to have returned to Montreal. From there, in 1685, he traveled to Lake Michigan. Then he went to the Cumberland River in Tennessee. He was looking for his wife and young daughter.

He traveled about 900 miles in 40 days. He found his way by following the river. When he found the Shawnee, they welcomed him. They invited him to live among them.

After finding his family, he visited the future site of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Then he crossed the Allegheny Mountains with them. They traveled along the Susquehanna River. His daughter, Mary Seaworth (Sewatha) Chartier (1687-1732), was born in Frederick County, Virginia in 1687.

Birth of Peter Chartier

In 1689, Chartier started a trading post at French Lick. This was on the Cumberland River in Middle Tennessee. It was near what is now Nashville, Tennessee. His son Peter (Pierre) Chartier was born here in 1690.

Peter Chartier later became a leader of the Pekowi Shawnee.

After Peter was born, Martin and his Shawnee family started a fur trading post. This was where the Monongahela River and the Allegheny River meet. This is the present-day site of Pittsburgh. The Ohio River starts here. They lived there for two years.

Moving to Maryland and Pennsylvania

In spring 1692, Chartier led a group of 192 Shawnee. An unknown number of Susquehannock (Conestoga) Indians also joined them. They moved east to Cecil County, Maryland on the Potomac River. The Shawnee were moving after fights with Illinois and Miami Indians. The Susquehannock had recently been defeated by the Iroquois. They formed an alliance with the Shawnee.

With Chartier's help, they planned to use the Susquehanna River to move furs. This was for the growing North American fur trade. Chartier was French by birth. But he wanted to use the competition between the French and British to help his Shawnee family.

English officials in Annapolis thought Chartier worked for the French. They ordered his arrest. He was jailed in St. Mary's and Anne Arundel counties. He was called "a spy or party with designs of mischief." He was released to wait for trial but escaped. He was caught again in August 1692 and jailed for three months. He was released on October 29, 1692.

Casperus Augustine Herman, a Maryland landowner, wrote to Governor Lionel Copley in February 1693. He said Martin Chartier was "a man of excellent parts." He added that Chartier spoke several languages and had been a carpenter's apprentice. Chartier and his family lived on Bohemia Manor in Maryland in 1693.

Chartier and his Shawnee group felt unwelcome. They moved north into Pennsylvania in 1694. They settled in a place that became known as Chartier's Old Town (later Tarentum, Pennsylvania). He kept a good relationship with the government. He sometimes worked as an interpreter and a link between the government and the Native Americans.

By the late 1690s, the Canadian fur trade had grown very large. There were too many furs in Quebec, which made prices drop. For a few years, Chartier and his French-Canadian friends Peter Bisaillon and Jacques Le Tort ran a smuggling operation. They brought furs from Detroit to Albany and Pennsylvania. The English paid more for them there.

The Chartier and Conestoga Alliance

In 1701, Chartier and his Shawnee community invited the Conestoga to live with them. The Conestoga had been greatly reduced by war and disease. Both the Conestoga and the Shawnee met with William Penn. On April 23, 1701, they were officially allowed to live together. They created the community of Conestoga Town near Manor Township, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. Years later, in December 1763, the descendants of these Native Americans were killed by the Paxton Boys.

French Traders in Pennsylvania

By the late 1600s, French settlers and fur traders moved into the Ohio Valley. This area was then part of New France. They wanted to trade with different Native American tribes living there. Some tribes had been pushed away from the east coast by European settlers. Chartier and his friends, Peter Bisaillon, Nicole Godin, Jacques Le Tort, his son James, and Le Tort's wife Anne Le Tort, were important coureurs des bois. They were experienced in frontier life and spoke several Native American languages. They set up some of the first trading posts.

The British government in Pennsylvania thought they were "very dangerous persons." They believed these traders "kept private correspondence with the Canida Indians and the French." They also thought they "entertained strange Indians in remote and obscure places" and "uttered suspicious words." This group was often bothered, arrested, and jailed by the English. These charges were often false or minor.

Arrest of Nicole Godin

Chartier avoided trouble by agreeing to help arrest Nicole Godin. At that time, both French and British governments wanted to influence Native American communities. They wanted them to choose a side for trade and political control. Nicole Godin was an English trader born in London to a French father. After 1701, he ran a trading post near Chartier's home. He was suspected of trying to make the local Shawnee angry at the British. He was also suspected of trying to make them join the French.

On May 15, 1704, Chartier was called to Philadelphia. William Penn questioned him about his connections with the Native Americans. Penn noted that Chartier was "a Frenchman, who has lived long among the Shawanah Indians and upon Conestoga." On July 1, 1707, Pennsylvania Governor John Evans convinced Chartier to help trap Godin near Paxtang, Pennsylvania. Godin was arrested there. Godin was tried for treason in Philadelphia in 1708, but the outcome of the trial is not known. He died before 1712.

Later Life and Death

Chartier was an interpreter for the Shawnee. He helped them at meetings with the English in Conestoga in 1711 and 1717. In 1717, Governor Penn gave Chartier 300 acres of land. This land was along the Conestoga River in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. He and his son Peter Chartier set up a trading post near a Shawnee village. This village was on Pequeua Creek in Pennsylvania. That same year, he went with Christoph von Graffenried, 1st Baron of Bernberg on a trip. They went to Sugarloaf Mountain in Maryland. They traveled south to the Shenandoah Valley. There, they visited Massanutten Mountain. They were looking for silver ore, which a Swiss explorer had reportedly found years earlier.

Martin Chartier died in April 1718 on his farm in Dekanoagah, Pennsylvania. This was near the Susquehanna River. His funeral was on April 25. James Logan, who would later be Mayor of Philadelphia, attended. After the funeral, Logan took Chartier's 250-acre property. He claimed Chartier owed him money. Logan later sold the property to Stephen Atkinson.

In 1873, Chartier's grave was found by accident by John Stehman. Stehman owned the property then. Chartier was buried in the traditional Shawnee style. His helmet, a cutlass, and small cannon balls were buried with him.

A historical marker was put up in 1925 by the Lancaster County Historical Society. It stands at the site of his burial in Washington Boro, Pennsylvania. It is at the corner of River Road and Charlestown Road.

Legacy

Historian Stephen Warren says Chartier was very important. He helped the Shawnee communicate with the French and later the English.

Chartier chose to live with a Shawnee group that did not pick sides in the big power struggles. The European settlers he dealt with always watched him closely. But the Shawnee valued him. He shared his knowledge of Europeans with them. This helped the Shawnee understand the newcomers. Chartier became their cultural broker.

For Shawnee people who moved around, being near settlers helped them survive. The Shawnee learned from people like Martin and Peter Chartier. These men moved between different regions and empires in their lives. Like the Chartiers, the Shawnee did not give in to French, English, or Iroquois rule. They were very independent. Shawnee people made careful choices based on the facts of Native American slavery, wars between tribes, and getting European trade goods.

Images for kids

-

Historical marker, erected in 1925, in Washington Boro, Pennsylvania, commemorating the life of Martin Chartier

See also

In Spanish: Martin Chartier para niños

In Spanish: Martin Chartier para niños

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |