Canadian canoe routes facts for kids

This article explores the amazing Canadian canoe routes used by early explorers and traders in Canada. These water highways were super important for the North American fur trade, especially for trading beaver furs.

Contents

- Exploring Canada by Canoe: The Water Highways

- St. Lawrence River Basin: The Main Gateway West

- Nelson River Basin: To Lake Winnipeg and Beyond

- Mackenzie River Basin: Furs from the Far North

- Pacific Coast: Linking East and West

- Mississippi Basin: French Connections South

- Lake Champlain-Hudson River: A Path of Conflict

- Hudson Bay: The Northern Trade Hub

- Images for kids

- See also

Exploring Canada by Canoe: The Water Highways

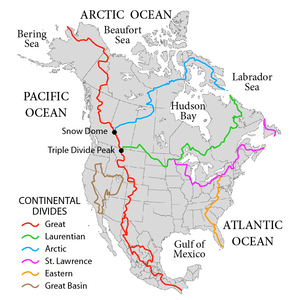

Early European explorers mainly traveled across Canada using its many rivers. The land has lots of rivers you can travel on, with only short breaks (called portages) where you had to carry your canoe. There were no big mountains or obstacles to stop water travel east of the Rocky Mountains. The fur trade, mostly for beaver furs, helped pay for and drive this exploration and early settlements. Traders got furs from Indigenous peoples and sent them to Europe.

Canada's Waterways: Like Siberia's Rivers

Both Canada and Siberia have huge boreal forests. Both were explored by fur traders using rivers. The main challenge was finding rivers that flowed in the right direction. Then, they needed short portages to move from one river system to another. Both regions are quite flat. You could travel from the St. Lawrence River all the way to the Rockies, or from the Urals almost to the Pacific, with just a few short portages. In both places, Indigenous people gathered furs, and Europeans exported them.

Russian expansion into Siberia began in 1582. They reached the Pacific Ocean just 57 years later. European settlement in Canada started in 1605 (at Port Royal, Nova Scotia) and 1608 (Quebec City). Explorers from Canada reached the Arctic Ocean in 1789 and the Pacific in 1793. Both these trips were led by Alexander Mackenzie.

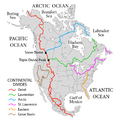

Main Entry Points to the Continent

Explorers naturally wanted to travel as far as possible by water. Hudson Bay takes you more than a third of the way across the continent. However, it leads to less productive areas and is frozen for most of the year. The Mississippi River was a natural entry point, but it wasn't used much until 1718 when New Orleans was founded. Early ships could go up the Hudson River to Albany. But this led north to the St. Lawrence, and travel west was blocked by the Iroquois people. The Chesapeake and Delaware Bays don't go very far inland. Other east coast rivers are too short or shallow. This left the St. Lawrence River as the best way in.

Two Eras of Trade and Exploration

French Era: In the 1500s, cod fishermen started trading for furs, especially at Tadoussac on the St. Lawrence River. After Quebec was founded in 1608, French traders called Coureurs des bois spread out. They used the many rivers and lakes to trade with Indigenous peoples. Indigenous people also brought canoe-loads of fur down to Montreal. Nearby tribes became middlemen, getting furs from further inland. Montreal was the main base where furs were stored before being shipped to Europe. By the end of this period, trade and exploration had reached all the Great Lakes and was moving down the Mississippi. Meanwhile, the British had posts on Hudson Bay. They mostly waited for Indigenous people to bring furs to them.

British Era: The second era began when trade reached the "pays d'en haut" (upcountry) west of Lake Superior. In these cold lands, beavers had longer, thicker fur. After the British took over Canada in 1759, English-speakers managed the Montreal trade. But French-Canadians still did the hard work. The Montreal-based North West Company was formed in 1779. This was because distances were so huge that they needed a very organized transport system. For example, the Athabasca region was 3000 miles from Montreal! A canoe might travel 1000 miles in a month.

The independent coureur des bois was replaced by hired workers called voyageurs. Since the western country was too far for a round trip in one season, boats would leave Montreal each spring when the ice broke. Winterers would start east. They exchanged their goods at Grand Portage on Lake Superior. Then they returned before the rivers froze five months later. To save money on hauling food from Montreal, Métis people around Winnipeg started making lots of pemmican. Pemmican is a dried meat and fat mixture that was a super important food for voyageurs.

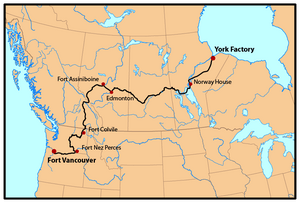

The Hudson Bay Company (HBC) trade was moved southwest to the edge of the prairie. Here, pemmican was picked up to feed the voyageurs on their journey northwest to the Athabasca country. Competition from the Nor'Westers forced the HBC to build posts inland. The two companies competed for a while and then merged in 1821. The HBC took over management because they had more money. But they used the trading methods of the Montreal-based Nor'Westers. Much trade shifted to York Factory. Later, some went south to Minnesota. After 1810, the western posts were linked to British bases on the Oregon coast. By the mid-1800s, the HBC controlled a huge inland empire. It stretched from Hudson Bay to the Pacific. The Carlton Trail became a land route across the prairies. HBC land claims were given to Canada by the Rupert's Land Act 1868. From 1874, the North-West Mounted Police started bringing formal government to the area. The fur trade routes became less important after the 1880s when railways and steamships arrived.

St. Lawrence River Basin: The Main Gateway West

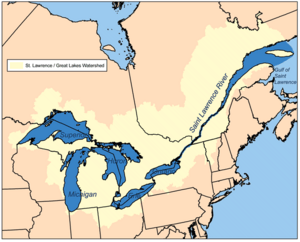

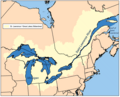

Large ships can reach Quebec City, and smaller ones can reach Montreal. You might think the route would continue up the St. Lawrence. But this wasn't the main way. Reasons included the Lachine Rapids and other rapids above Montreal, Niagara Falls, and the Iroquois people being unfriendly. Also, the furs from the south weren't as good, and there weren't enough large birch trees to make canoes.

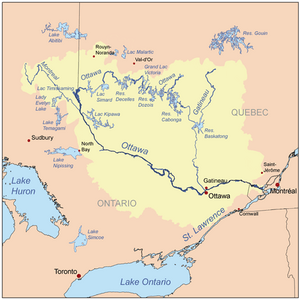

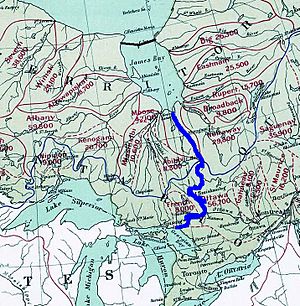

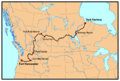

The route west from Montreal was called the 'first Trans-Canada Highway'. It went from near Montreal, up the Ottawa River, west up the Mattawa River to Trout Lake. Then, it crossed the 7-mile La Vase portage at what is now North Bay on Lake Nipissing. From there, it went down the French River to Georgian Bay of Lake Huron. Étienne Brûlé first used this route in 1610, and Samuel de Champlain used it later. When the Iroquois made the Ottawa River dangerous, small canoes could continue up the Ottawa above the Mattawa. From its sources, they could cross to the Saint-Maurice River and go down to the St. Lawrence at Trois-Rivières.

Routes also went from the French River south to the Jesuit Huron missions at the southern end of Georgian Bay (1626–1640). Or they went west through the Strait of Mackinac to Lake Michigan. Another option was west, north of Manitoulin Island, and up the St Marys River (with a 26-foot elevation difference) to Lake Superior. On Lake Superior, voyageurs usually stayed close to the northern shore. This was because strong winds could often overturn their boats.

The route up the St. Lawrence to Lake Ontario, past Niagara Falls, to Lake Erie, the Detroit River, Lake St. Clair, St. Clair River, and lower Lake Huron developed later. Adrien Jolliet was probably the first to use it in 1669. But it was never the main route west. North of the St. Lawrence were many complex lakes and rivers. These were sometimes used to go as far as James Bay. The Toronto Carrying-Place Trail was a major portage route in the St. Lawrence basin. It connected Lake Ontario with Lake Simcoe and the northern Great Lakes.

Nelson River Basin: To Lake Winnipeg and Beyond

The Canada–United States border meets Lake Superior near Grand Portage, Minnesota. From here to Lake of the Woods, the voyageurs' route went northwest. They crossed the 9-mile (14 km) long Grand Portage to avoid the falls and canyon of the Pigeon River. Then, they followed the current international border west up the 50-mile long Pigeon River and Arrow River to South Lake. After that, they crossed the 400-meter Height of Land Portage to North Lake. The waters of North Lake drain into Hudson Bay.

From North Lake, the route goes through Gunflint Lake. Then, it goes down the Pine and Granite Rivers to Saganaga Lake. It continues through a chain of lakes, including Knife and Basswood Lakes, to Lac La Croix. Here, the route from Fort William joins in. It goes down the Loon River to Lake Namakan. Then, it crosses either of two portages to Rainy Lake. A supply depot was set up here to shorten the trip for the Athabasca brigade. The route continues down the Rainy River to Lake of the Woods, 210 miles west-northwest of Grand Portage.

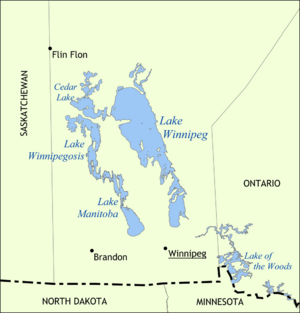

Leaving the US border, the route goes northwest down the Winnipeg River. This river has 26 portages before reaching Lake Winnipeg, which is a difficult lake for small boats. La Vérendrye explored this area between 1731 and 1737. Following the current downstream leads to the Nelson River and Hudson Bay, which wasn't very useful for the fur trade. The Nelson River is hard to travel on, so the parallel Hayes River was preferred. The Hayes route became more important after 1821 when much trade moved from Montreal to York Factory.

In 1803, it was discovered that Grand Portage was on the US side of the border. So, the Lake Superior base was moved 45 miles northeast to Fort William, Ontario. From Fort William, an old trail led inland north and west to Lac La Croix in the Rainy River watershed.

A smaller route went from Duluth, Minnesota west and north up the St. Louis River and Embarrass River. It crossed another Height of Land Portage and went north down the Pike River (Minnesota) and Vermilion River (Minnesota) to Rainy Lake on the Grand Portage route.

The Saskatchewan River enters Lake Winnipeg at Grand Rapids, Manitoba. Around these rapids, the route goes to Cedar Lake. Although not used much, a route went from Cedar Lake south over the 4-mile Mossy portage to Lake Winnipegosis. Then, it crossed the 1.5-mile Meadow Portage to Lake Manitoba. Finally, it went over at least 5 miles of Portage la Prairie to the Assiniboine River. Another route reached Lake Manitoba from Lake Winnipeg via the Dauphin River.

Up the Saskatchewan River, past Cumberland House, and up the North Saskatchewan River, the route went almost to the Rocky Mountains at Fort Edmonton and Rocky Mountain House, Alberta. The North Saskatchewan River is roughly the southern edge of the forested beaver country. There are no portages between Cumberland and Edmonton. However, there are sand bars and a 125-mile stretch of strong current east of Prince Albert, Saskatchewan. Here, canoes had to be pulled upstream with ropes. Above Prince Albert is the La Montée prairie country. Here, voyageurs were fed by buffalo hunters. Both York boats and north canoes were used. Trade was easier because the Cree Language was spoken along the whole route. South of the river, there was enough grass for horses. You could travel from Edmonton to Red River on horseback. Horses were used for speed, and canoes for carrying goods. Of course, there are no canoe routes over the Rockies.

The Assiniboine River, which meets the Red River of the North just south of Lake Winnipeg, provided another route west. The Red River, which flows north into the southern tip of Lake Winnipeg, became more important after 1812. This was when the Red River Colony was established. Also, the Métis people started supplying buffalo Pemmican to feed the voyageurs. These are prairie rivers and not good beaver country. Much transport was by horse and Red River cart. American traders were able to get around the British fur trade monopoly. They took much of the trade to trading posts on the Mississippi River to the south using the Red River Trails.

Mackenzie River Basin: Furs from the Far North

The route from Lake Superior to the Mackenzie River runs along the southwest side of the forested beaver country. This area is between the prairie to the southwest and the Barren Grounds to the northeast. Here, beaver fur is longer and thicker than further southeast. The southern part of this route was near where pemmican was made.

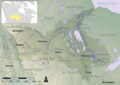

From the depot at Cumberland House, Saskatchewan on the lower Saskatchewan River, this route goes north up the Sturgeon-Weir River. It crosses Frog Portage to the east-flowing Churchill River, which is mostly a chain of lakes. It goes west up the Churchill past the depot on Lac Île-à-la-Crosse, through Peter Pond Lake to Lac La Loche. Then, it crosses the 12-mile Methye Portage to the Clearwater River. The waters of the Clearwater River reach the Arctic Ocean. The Methye Portage, first reached by Peter Pond in 1778, was one of the most difficult major portages.

The route continues west down the Clearwater River to the Athabasca River at Fort McMurray. It goes north down the Athabasca to the Peace-Athabasca Delta and the depot at Fort Chipewyan, Alberta, at the west end of Lake Athabasca. This was about as far as canoes could go and return in one season. It was the gathering place for furs from the rich Athabasca region and further west. You could continue into less productive country north down the Slave River to the Great Slave Lake. From there, you could go northwest down the Mackenzie River to the Arctic Ocean.

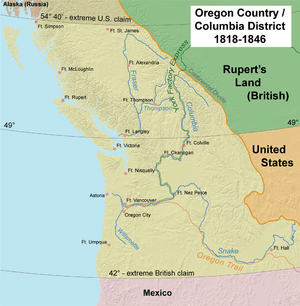

Pacific Coast: Linking East and West

After the voyages of Captain Cook, European ships entered the Pacific in large numbers. A Maritime fur trade with China developed from the Columbia District (known as Oregon Country in the US). The inland canoe routes were linked to the Pacific coast in 1811 when David Thompson reached the mouth of the Columbia River. A fur trade grew in the interior. Here, horses were used more often than canoes. Furs were trapped by non-Indigenous people, and the pelts were exported by ship. Here, Canadians competed successfully with the American Fur Company. In 1846, the Columbia District was divided between the two nations at the 49th parallel.

The interior of British Columbia around the upper Fraser River was called New Caledonia. Goods were carried from Fort Chipewyan up the Peace River (1,500 feet elevation gain and only one major portage at Hudson Hope, British Columbia) to Fort McLeod. Then, they were carried over the mountains. It usually took two years for heavy goods to cross the continent. Goods were stored at Fort Chipewyan over the winter. Later, there was a horse trail from the Fraser River south to Fort Okanogan on the Columbia River.

The route to the Columbia River went from Fort Chipewyan southwest up the Athabasca River to Fort Assiniboine. After 1825, it went west from Fort Edmonton on the North Saskatchewan over an 80-mile horse track to Fort Assiniboine. From there, it went up the Athabasca to Jasper House. Then, it crossed Athabasca Pass to Boat Encampment on the Columbia. This route was used for messages and light goods. But it wasn't practical for heavy freight.

The far northwest was supplied by a unique route found in 1851 by Robert Campbell. He traveled in the opposite direction. From the Mackenzie River delta, it went south up the Peel River to the depot at Fort McPherson, Northwest Territories. Then, it went back down the Peel and west up the Rat River (by pushing or dragging, not paddling) or by a parallel trail. It crossed a half-mile portage to the Little Bell River. The route from Bell River (Yukon) went past a post called Lapierre's House and down the Porcupine River to Fort Yukon, Alaska, about 300 miles west of Fort McPherson. From there, it went at least 400 miles south-southeast up the Yukon River and Pelly River. Then, it followed the Findlayson and Campbell Rivers and a portage to Frances Lake. It went down the Frances River to the Liard River and east to Fort Simpson on the Mackenzie, about 275 miles east of Frances Lake. There was some transport on the Liard, but the Liard River canyon made this difficult.

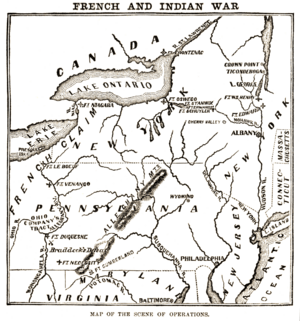

Mississippi Basin: French Connections South

In 1682, La Salle reached the mouth of the Mississippi from the Great Lakes. From about 1715, the French tried to connect the St. Lawrence and Mississippi basins. They wanted to keep the English on the east coast. From the southeast side of Lake Michigan, the route went east up the St. Joseph River to near South Bend, Indiana. It crossed a short portage to the Kankakee River. Then, it went west down the Kankakee, which joins the Des Plaines River to become the Illinois River. This river runs first west and then southwest to the Mississippi.

Another route was the Chicago River and across the Chicago Portage to the Des Plaines River and south to the Illinois. Alternatively, from the northwest side of Lake Michigan, at the head of Green Bay, the route went up the Fox River. It passed serious rapids to Lake Winnebago, up the Fox, and over a short portage to the Wisconsin River and southwest to the Mississippi. Another route went from the western end of Lake Superior up the Saint Louis River and the East Savanna River. It crossed the Savanna Portage and went down south and west flowing streams to the Mississippi River. This led to the fur country of what is now the U.S. state of Minnesota.

By the time the British conquered Canada, there were French trading posts from New Orleans up the Mississippi and Illinois Rivers to the Great Lakes.

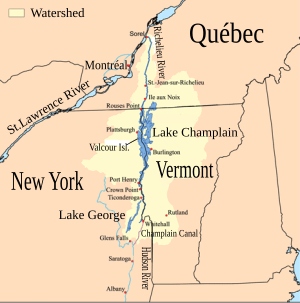

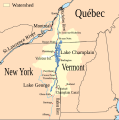

Lake Champlain-Hudson River: A Path of Conflict

This route was a main area of military conflict between the British and French, and later the British and Americans. From Quebec, it went upriver about a third of the way to Montreal. Then, it went up the Richelieu River to Lake Champlain. There was a portage west, parallel to the La Chute River (a 230-foot drop in 3.5 miles) to Lake George. From there, it went overland to the Hudson River and downstream to New York.

Hudson Bay: The Northern Trade Hub

The Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) started setting up posts on the Bay in 1668. Unlike the French-Canadians, the English usually stayed on the coast. They let Indigenous people bring furs to them. Joseph Robson described it as "asleep by the frozen sea." Movement inland began around 1750. This was after the French entered the western country and tried to redirect the Hudson Bay fur trade to Montreal.

The most important route went from York Factory up the Hayes River (not the Nelson River) to Norway House at the north end of Lake Winnipeg. Most HBC posts were on the southwest side of the bay. Inland, there were many complex routes. Most were too small for heavy freight canoes.

Main routes from east to west were:

- On James Bay

- North of the Eastmain were Barren Grounds with few beaver.

- Eastmain River from James Bay east.

- Rupert River with Rupert House: From Rupert Bay at the southeast corner of James Bay, east up the Rupert to Lake Mistassini. Then, over to Lake Saint-Jean and down the Saguenay River to the St. Lawrence at Tadoussac.

- Nottaway River: From Rupert Bay southeast to Lake Matagami.

- Moose River with Moose Factory on the south end of James Bay:

- 1) South: Moose River, Abitibi River, Lake Abitibi, portage to the upper Ottawa River near Lake Timiskaming. This was the best route from James Bay to the Ottawa. The Hudson Bay expedition (1686) used it.

- 2) Southwest: Moose River, Missinaibi River, portage to the Michipicoten River to Lake Superior at Wawa, Ontario. This route supplied Lake Superior from Hudson Bay.

- Albany River with Fort Albany, Ontario on the west side of James Bay with Henley House (1743) 160 miles upstream:

- 1) Southwest: Up the Albany, up the Ogoki River, cross to Lake Nipigon and south to Lake Superior.

- 2) West: Albany River to Lake St. Joseph, portage to a river going south to Lac Seul and down the English River (Ontario) to the Winnipeg River.

- Severn River (northern Ontario) with Fort Severn on the 'shoulder' west of James Bay. The Severn flows northeast from the general area of Lake St. Joseph.

- Hayes River with York Factory, Manitoba: York Factory was the Hudson's Bay Company's main base. Up most of the Hayes, across the Echimamish River to the upper Nelson River and upstream to Norway House, Manitoba at the north end of Lake Winnipeg. (Close by is the mouth of the Saskatchewan River, used to reach parts of the Prairies).

- Nelson River with Port Nelson just north of the mouth of the Hayes. Although the Nelson drains Lake Winnipeg, this route was avoided. The Hayes was preferred.

- Churchill River (Hudson Bay) with Fort Churchill: This route was mainly used by Chipewyans to bring furs down from the rich Athabasca country. The route went from the east end of Lake Athabasca up the Fond du Lac River (Saskatchewan) to Wollaston Lake. Then, it went south through Reindeer Lake to the Churchill. George Simpson used this route in 1824. But Europeans rarely used it because the large lakes stay frozen late into the season.

- Inland between the Churchill and Hayes Rivers: Smaller Indigenous canoes used the Upper and Middle Tracts between the Hayes and Nelson. These routes became less important after 1774. This was when Cumberland House, Saskatchewan was founded. It allowed transport by heavy freight canoes and York boats.

- Middle Tract: One branch left the Hayes about 100 miles from the Bay. It went up the Fox River (Manitoba) and Bigstone River to Utik (Deer) Lake. Then, it somehow crossed to Cross Lake, Manitoba on the Nelson. The other left the Hayes at Oxford Lake. It went up the Carrot River and crossed to Walker Lake, which connects to Cross Lake about 50 miles west of Oxford Lake. From the west end of Cross Lake, it went up the Minago River and over a low divide to Moose Lake. Then, it went along the Summerberry River to the Saskatchewan River.

- Upper Tract: Began on the Nelson River at Split Lake, Manitoba. It avoided about 150 difficult miles of the lower Nelson. It went about 200 miles west-southwest up the Grass River. It crossed the Cranberry Portage to the Goose River. Then, it went down the Goose and Sturgeon-Weir River to Cumberland Lake on the Saskatchewan River, about 50 miles west of the start of the Middle Tract.

- Another route connected the Nelson and Churchill. It went from Split Lake west up the Burntwood River and a portage via the Kississing River to the Churchill. Then, it went up to Frog Portage.

- North of the Churchill is Barren Grounds.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Primeras rutas canadienses en canoa para niños

In Spanish: Primeras rutas canadienses en canoa para niños

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |