Apalachee facts for kids

Apalachee territory in the Florida Panhandle

|

|

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| extinct as a tribe | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| United States Florida, southwestern Georgia | |

| Languages | |

| Apalachee | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| other Muskogean peoples |

The Apalachee were an Indigenous people who lived in what is now the Florida Panhandle. They lived there until the early 1700s. Their land was between the Aucilla River and Ochlockonee River. This area was known as the Apalachee Province.

The Apalachee spoke a language called Apalachee. It was a Muskogean language. Sadly, this language is now extinct.

The Apalachee lived at the Velda Mound site around 1450 CE. They had mostly left it by the 1600s when Spanish settlers arrived. They first met Spanish explorers in 1528. This was when the Narváez expedition came to their lands. Their population greatly decreased due to tribal enemies, European diseases, and new settlers.

From 1701 to 1704, wars badly affected the Apalachee. They left their homes by 1704. Many fled north to the Carolinas, Georgia, and Alabama.

Contents

Apalachee Language

The Apalachee language was a Muskogean language. Not much is known about it. It became extinct in the late 1700s. The only Apalachee document that still exists is a letter. It was written in 1688 by Apalachee chiefs to the Spanish king.

What Does "Apalachee" Mean?

The name Apalachee might come from the Hitchiti language. It could mean "people on the other side." Or it might come from the Choctaw language word apelachi, meaning "a helper." The name has also been spelled Abalache, Abalachi, or Abolachi.

Apalachee Culture

The Apalachee are thought to be part of the Fort Walton Culture. This was a Florida culture. It was influenced by the Mississippian culture.

The Apalachee grew crops like corn, beans, and squash. They lived in settled towns and villages. Their society had different levels, with important chiefs. Like many other tribes in the Southeast, they had two main leaders. One was a war chief, and the other was a peace chief. Leadership was passed down through the mother's side of the family.

When Hernando de Soto visited in 1539 and 1540, the Apalachee capital was Anhaica. This is near present-day Tallahassee, Florida. The Apalachee lived in villages of different sizes. Some lived on small farms. Smaller settlements might have one earthwork mound and a few houses. Larger towns had 50 to 100 houses. These were chiefdoms. They were built around earthwork mounds. These mounds were used for ceremonies, religious events, and burials.

Villages and towns were often near lakes. The people fished there. They also used the water for daily needs and travel. The biggest Apalachee community was at Lake Jackson. This is just north of Tallahassee. This important center had several mounds and over 200 houses. Some of these mounds are now protected in Lake Jackson Mounds Archaeological State Park.

The Apalachee grew maize (corn), beans, and squash. They also grew amaranth and sunflowers. They gathered wild plants too. These included persimmons, maypops, acorns, and walnuts. They hunted animals like deer, black bears, rabbits, and wild turkeys.

The Apalachee were part of a large trade network. It stretched from the Gulf Coast to the Great Lakes. It also went west to what is now Oklahoma. Through this trade, the Apalachee got copper items, sheets of mica, and galena. They likely paid for these goods with shells, pearls, shark teeth, and dried fish. They also traded salt and cassina leaves. These leaves were used to make a special drink.

The Apalachee made tools from stone, bone, and shells. They made pottery and wove cloth. They also prepared buckskin. Their houses were covered with palm leaves or tree bark. They stored food in pits in the ground. They also smoked or dried food over fires. When Hernando de Soto took over the Apalachee town of Anhaico in 1539, he found enough food to feed his 600 men and 220 horses for five months.

Apalachee men wore a deerskin loincloth. Women wore skirts made of Spanish moss or other plant fibers. Men painted their bodies with red ochre. They put feathers in their hair when getting ready for battle. Men smoked tobacco in special ceremonies, including those for healing.

Apalachee warriors wore headdresses made of bird beaks and animal fur. If a warrior was killed, his village or family was expected to get revenge.

The Apalachee Ball Game

The Apalachee played a ball game. Spaniards described it in the 1600s. It was a very important part of their culture. The game was connected to many traditions.

A village would challenge another village to a game. They would then agree on a day and place to play. After the Spanish missions were built, games often took place on Sunday afternoons. Teams would kick a small, hard ball. It was made by wrapping deerskin around dried mud. The goal was to hit a single goalpost.

The goalpost was triangular and flat. It was taller than it was wide. It had snail shells, a nest, and a stuffed eagle on top. Benches were placed for the teams. People watching would bet personal items on the games.

Each team had 40 to 50 men. The best players were highly valued. Villages would give them houses and help them with their fields. Play was very rough. Players would try to hide the ball in their mouths. Other players might try to force the ball out. Sometimes, players got seriously hurt.

The game had a detailed origin story. Challenging a team and setting up the game followed strict rules. Even after Christianity arrived, some Christian elements became part of the game.

Apalachee Diet

The Apalachee were skilled hunters and fishermen. They hunted animals like deer, rabbit, and turkey. Corn (maize), beans, and squash were a main part of their diet. They also gathered wild fruits, berries, and nuts.

Apalachee History

The Apalachee had a complex society with many people. They were one of the Mississippian cultures. They were part of a large trade network that reached to the Great Lakes. Their reputation was so strong that other tribes told Spanish explorers that riches could be found in Apalachee land.

The name "Appalachian" comes from the Narváez Expedition. In 1528, they met the Tocobaga tribe. The Tocobaga spoke of a land called Apalachen far to the north. Weeks later, the expedition entered the Apalachee territory. This was north of the Aucilla River. Later, the Hernando de Soto expedition reached the main Apalachee town of Anhaica. This was near present-day Tallahassee, Florida. The Spanish then used the name Apalachee for the coastal area and the tribe. "Appalachian" is one of the oldest European place names still used in the United States.

Spanish Encounters

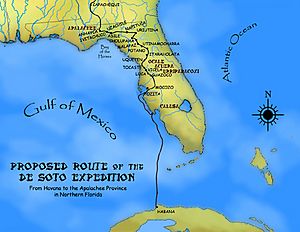

Two Spanish expeditions met the Apalachee in the early 1500s. The expedition of Pánfilo de Narváez entered Apalachee land in 1528. The Apalachee fought back against the Spanish attacks. The Narváez expedition then fled to Apalachee Bay. They built five boats and tried to sail to Mexico. Only four men survived this difficult journey.

In 1539, Hernando de Soto landed on the west coast of Florida. He had many men and horses. He was looking for gold. Native Americans told him that gold could be found in "Apalachee." Historians are not sure if they meant the mountains in northern Georgia (where gold was found) or valuable copper items the Apalachee traded for. Either way, de Soto went north to Apalachee land looking for metal.

The Apalachee feared and disliked the Spanish. This was because of their past experience with Narváez. Also, they heard about fighting between de Soto's group and other tribes. When de Soto's expedition entered Apalachee land, the Spanish soldiers were very aggressive. De Soto and his men took over the Apalachee town of Anhaica. They stayed there for the winter of 1539 and 1540.

The Apalachee fought back with quick raids and ambushes. Their arrows could go through two layers of chain mail. They aimed for the Spaniards' horses. Horses gave the Spanish an advantage over the Apalachee, who fought on foot. In the spring of 1540, de Soto and his men left Apalachee land. They headed north into what is now Georgia.

Spanish Missions and 1700s Warfare

Around 1600, Spanish Franciscan priests started successful missions among the Apalachee. They built more settlements over the next century. The Apalachee may have accepted the priests because their population had decreased. This was due to infectious diseases brought by Europeans. Many Apalachee became Catholic. They blended their old traditions with Christianity. In February 1647, the Apalachee rebelled against the Spanish. This happened near a mission called San Antonio de Bacuqua in Leon County, Florida. The revolt changed how the Spanish treated the Apalachee. After the revolt, Apalachee men were forced to work on projects in St. Augustine or on Spanish farms.

San Luis de Talimali was the western capital of Spanish Florida from 1656 to 1704. It is now a National Historic Landmark in Tallahassee, Florida. This historic site is a living history museum. It shows what one of the Spanish missions was like. It also shows Apalachee culture and how the Apalachee and Spanish lived closely together.

In the 1670s, tribes north and west of the Apalachee raided Apalachee missions. These tribes included the Chiscas and Yamasees. They captured people. They traded these captives to the British colony of Carolina. There, they were forced to work for the colonists. The Spanish could not fully protect the Apalachee. So, some Apalachees joined their enemies. Apalachee raids to capture English traders pushed the raiders' camps eastward. From there, they continued to raid Apalachee missions. Efforts were made to build missions along the Apalachicola River to create a safe area. In 1702, the Apalachicolas ambushed nearly 800 Apalachee, Chacato, and Timucuan warriors. Only 300 warriors escaped.

When Queen Anne's War started in 1702, England and Spain were at war. Raids by English colonists and their Native American allies increased. These raids targeted the Spanish and the Mission Indians in Florida. In early 1704, Colonel James Moore led 50 colonists and 1,000 Apalachicolas and other Creeks. They carried out a series of raids on Spanish missions in Florida. Some villages surrendered, while others were destroyed. Moore returned to Carolina with 1,300 Apalachees who had surrendered. Another 1,000 were taken captive. In mid-1704, another large Creek raid captured more missions and many Apalachees. Missionaries and Christian Native Americans were killed in both raids. These raids became known as the Apalachee massacre.

When rumors of a third raid reached the Spanish in San Luis de Talimali, they decided to leave the area. About 600 Apalachee survivors of Moore's raids settled near New Windsor, South Carolina. After the Yamasee War, this group joined the Lower Creek. Many later returned to Florida.

When the Spanish left Apalachee province in 1704, about 800 surviving Native Americans fled west to Pensacola. This included Apalachees, Chacatos, and Yamasee. Many Spanish people from the province also went with them. The Apalachees were not happy in Pensacola. Most moved further west to French-controlled Mobile. They faced a yellow-fever epidemic there and lost more people.

Later, some Apalachees moved to the Red River in present-day Louisiana. Others returned to the Pensacola area. A few Apalachees returned to Apalachee province around 1718. They settled near a new Spanish fort at St. Marks, Florida. Many Apalachees from the village of Ivitachuco moved to a place called Abosaya. This was near a Spanish ranch in what is now Alachua County, Florida. In late 1705, the remaining missions and ranches in the area were attacked. Abosaya was under attack for 20 days. The Apalachees of Abosaya moved south of St. Augustine. However, most of them were killed in raids within a year.

The group on the Red River in Louisiana joined with other Native American groups. Many eventually moved west with the Muscogee.

When Florida was given to Britain in 1763, some Apalachee families moved to Veracruz, Mexico. They had been living near the Spanish fort of Pensacola. Eighty-seven Native Americans living near St. Augustine were taken to Guanabacoa, Cuba. Some of these may have been descendants of the Apalachee.

In the late 1700s, some remaining Apalachees who had become Christian joined with the Lower Creeks and other nearby tribes. They became part of the Seminoles.

Cultural Heritage Groups

Today, several groups say they are descendants of the Apalachee people. However, none of these groups are officially recognized by the U.S. government or by states. These unrecognized tribes include:

- Talimali Band of Apalachee Indians of Pineville, Louisiana

- Apalachee Indian Tribe of Alexandria, Louisiana

- Apalachee Indians Talimali Band of Stonewall, Louisiana.

See also

In Spanish: Apalache para niños

In Spanish: Apalache para niños

- Anhaica

- Leon-Jefferson culture

- List of Native American peoples in the United States

- List of sites and peoples visited by the Hernando de Soto Expedition

- List of unrecognized tribes in the United States

- Mississippian shatter zone

- Muskogean languages

- Queen Anne's War

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |