Mississippian culture pottery facts for kids

Mississippian culture pottery is the amazing clay art made by the Mississippian culture people. They lived in what is now the American Midwest and Southeast from about 800 to 1600 CE. You can find their pottery as artifacts (old objects) at archaeological sites.

One special thing about Mississippian pottery is that it often has ground-up river mussel shells mixed into the clay. This is called "shell-tempering" and it's a key sign of Mississippian culture. By studying how this pottery was made, its shapes, and designs, archaeologists learn a lot about how these ancient people lived, what they believed, and how they traded with each other.

Contents

How Mississippian Pottery Was Made

Mississippian pottery was made from clay found nearby. This helps archaeologists figure out where a pot came from. To stop the clay from shrinking and cracking when it dried and was heated, potters added things to it. This is called "temper." Most often, they used ground-up mussel shells. Sometimes, they used crushed pieces of old pots, which is called "grog tempering." This was a method used by older cultures.

Potters built their pots by hand. They didn't use a potter's wheel. They often used the "coiling" method. This is where they rolled clay into long ropes and then coiled them up to form the pot's shape. Then, they smoothed the walls. Sometimes, they added designs to the wet clay by pressing, cutting, or stamping. After a pot was completely dry, it was heated in a wood fire.

Most pottery found is a type called "Mississippian Bell Plain." It's a buff color and has large pieces of mussel shell in it. It's not as smooth as other types. Fancier pottery used very finely ground shell, making it look smoother. Some special serving dishes and items buried with people had handles shaped like animal heads or were shaped like animals or humans. Women likely made most of the pottery, just like in many other Native American cultures. Archaeologists even found tools for polishing and shaping pottery in a woman's grave at the Nodena site.

It's easy to tell Mississippian pottery apart from older Woodland period pottery. Woodland pots were usually thicker, had flat or cone-shaped bottoms, and used sand or grog as temper. Mississippian pots were thinner, had tiny white flecks of shell, and often had round bottoms.

Why Shell Tempering Was Important

Shell tempering is a key sign of Mississippian cultures and their pottery. Around 800 CE, Mississippian people in the Central Mississippi Valley, like at Cahokia, started making pottery with shell temper.

Archaeologists studied why potters in the Mississippi Valley suddenly switched to shell temper. They found that the clay in this area, often called "gumbo" clay, was very sticky and shrank a lot when it dried. This made it hard to work with and caused pots to crack or even explode when fired. Older potters tried to fix this by adding a lot of sand or grog, but their pots had to be thick and flat-bottomed.

Adding shell temper helped a lot! Potters would collect freshwater mussel shells, which were often left over from eating the mussels. They would burn the shells, which made them easy to crush into fine, plate-like pieces. When these burned shell pieces were added to the sticky clay, it made the clay much easier to shape.

Even adding just a little bit (10-15%) of shell temper made the clay much better. The pots became lighter, stronger, and less likely to crack while drying. The shell also helped bind the clay, making the finished pots stronger. This meant potters could make thinner-walled pots. Thinner walls were great for cooking because heat could get to the food faster. Round bottoms were also better for cooking, allowing for even heating and stirring.

So, shell-tempered pottery made cooking much more efficient, especially for the growing amounts of maize (corn) being farmed. This helped support larger and healthier populations. Around 800 CE, shell-tempered pottery quickly spread from the middle Mississippi River valley. It became a big part of the growing Mississippian culture, along with other new tools for farming, hunting, and crafting. These improvements helped create the advanced societies that early European explorers saw in the 1500s.

Designs on Pottery

Many Mississippian pots have designs cut or scratched into them. Potters used sticks, reeds, or bone pieces to draw on wet clay or scratch designs into dry, unfired pots. Sometimes, they used sharpened reeds or even their fingernails to make small marks. These detailed designs often have special meanings, usually connected to the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex, which was a shared set of beliefs and symbols.

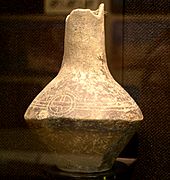

-

Ceramic beaker from Cahokia with an engraved woodhenge design

Painted Pottery

Mississippian potters also painted their pottery using special colored clays called "slips." They used galena for white, hematite for red, and sometimes graphite for black. Red and white spirals, fylfots (a type of cross), and striped bottles were popular, especially in the Central Mississippi Valley. Natural colors like red, orange, and brown came from ochre. They also used plant-based colors from roots, barks, and berries.

A cool technique called "negative painting" involved painting the background and letting the natural color of the clay show through to create the main image. Sometimes, they used beeswax or bear grease as a "resist" to protect parts of the pot from paint. This resist would melt away when the pot was fired.

-

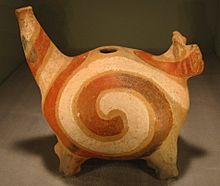

Painted Underwater panther effigy bottle from Cross County, Arkansas

Textile-Impressed Pottery

Some Mississippian pottery has patterns from textiles (fabrics) pressed onto it. They might have pressed plant fibers or netting onto the outside of a pot. Some archaeologists think these were old fabrics that were no longer used for clothes. Corncobs were also used to create textures on pots.

Pottery Shapes

Mississippian pottery came in many shapes and for many uses. They made small items like earplugs, beads, and smoking pipes. They also made everyday items like cooking pots, serving dishes, and bottles for liquids. Some unique shapes included human head pots or hooded vessels. Large pots were sometimes used as funeral urns to hold human remains.

The most common Mississippian pot shape is the "standard Mississippi jar." This is a round jar with a curved rim and a slight shoulder. In Florida, broken pot pieces were sometimes rounded and used as game pieces.

Effigy Pots

Effigy pots were very popular among many Mississippian groups. These pots were shaped like living things. Some looked like humans (anthropomorphic), some like animals (zoomorphic), and others like mythical creatures from the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex.

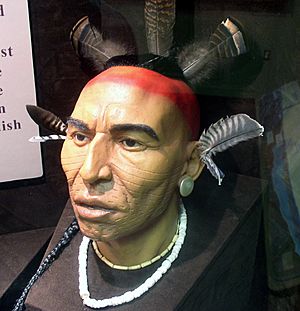

Head Pots

Head pots are jars shaped like human heads, usually male. They often look like they are of people who have passed away. They are typically 3–8 inches tall. Smaller ones are found in the Arkansas River Valley. These pots are often painted red, cream, and black on buff-colored clay. Most were made between 1200 and 1500 CE in the Central Mississippi Valley (Arkansas and Missouri). They are considered some of the most amazing and rare clay pots from North America.

About 200 complete or broken head pots exist today. Each one is unique. Because of their eye shapes and half-open mouths, people think they might show deceased individuals, like a kind of death mask. It's not clear if they were meant to be the heads of enemies or honored ancestors. The pots often have painted designs, lines that look like tattoos, and sometimes holes for ear and nose piercings. You can see some great examples at the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington D.C., the Hampson Archeological Museum State Park in Wilson, Arkansas, and the Parkin Archeological State Park in Parkin, Arkansas.

Hooded Bottles

Hooded bottles were round pots, like gourds, with a rounded bottom and a smaller "head." One side of the head looked like an animal or human face, and the other side was a dark, hollow opening. They were painted on the outside. One idea is that these were used to store seeds, with clay plugs sealing the opening. Another idea is that they held liquids. Owls and opossums are often seen on hooded vessels.

-

Hooded bottle from Arkansas, at the Gilcrease Museum

Pipes

Ceramic pipes often had animal shapes. L-shaped elbow pipes were the most common. A hollow reed or sourwood stem would be put into the pipe for smoking.

Salt Pans

Salt pans were large, oval, shallow clay pans used to make salt. They could hold a lot of liquid, from 10 to 26 liters. A thick clay coating made them more waterproof. They were likely shaped using a mold, perhaps a basket. They were lined with grass or textiles to keep them from sticking before they were fired.

Special Pottery Styles

Cahokian Pottery

Cahokia, the largest ancient city in North America north of Mexico, made some of the best and most widely spread pottery. Pottery from Cahokia was very fine, with smooth surfaces, thin walls, and special tempering and colors. Archaeologists can tell how these qualities changed over time, helping them date the pottery very accurately. Two important types, Powell Plain and Ramey Incised, appeared during the Stirling Phase. These pots mostly used shell temper. The inside of the broken pieces often showed grey, buff, or cream colors. Some were painted with liquid clay and color, usually red, grey, or black, and then polished to be very shiny.

Powell Plain pots were plain, but Ramey Incised pots were shiny and had designs cut into their upper shoulders. These designs often related to the underworld or water. The designs were added when the clay was still wet. These special pots were likely used by important leaders and for religious ceremonies. As Cahokia's influence spread, its fancy pottery went with it. People in other areas tried to copy these pots, though often not as skillfully. Cahokian-style pottery has been found far away, like in Aztalan in Wisconsin and Fort Ancient sites in Ohio.

How Cahokia Pottery Changed Over Time

| Time Period | Dates | Pottery Changes |

|---|---|---|

| Lohmann Phase | 1050 - 1100 CE | Most painted pottery was light red with shell temper. Black and brown pottery with grog and grit temper was still made. |

| Stirling Phase | 1100 - 1200 CE | Powell Plain and Ramey-Incised pottery appeared. Shell became the main temper. |

| Moorehead Phase | 1200 - 1275 CE | Limestone temper almost completely disappeared. |

| Sand Prairie Phase | 1275 - 1350 CE | Almost all pottery used shell temper. Powell Plain and Ramey Incised types were no longer made. |

Caddoan Pottery

The arrival of Europeans in the 1500s changed things for the Caddo people. Many people were lost, and their way of life changed. By the 18th century, the Caddo pottery tradition almost ended. By the late 1800s, only a few signs of it remained. However, in the 1990s, Jereldine Redcorn (a Caddo artist) worked hard to bring her tribe's pottery traditions back to life.

Moundville Pottery

At the Moundville Archaeological Site in Alabama, two main types of pottery are found. The Hemphill style pottery was made locally. It has special engraved designs and is found in graves and homes. The other type is painted pottery. Many of these painted pots were brought in from other places. Unlike the engraved pottery, the painted pottery seems to have been used mostly by the leaders at Moundville.

Hemphill Style Pottery

The Hemphill style pottery from Moundville is usually thin-walled bottles and bowls. They are made with finely ground mussel shell and polished to a shiny black. About 150 complete pieces are known. Most were found in graves, but some show signs of everyday use. This style has unique local designs, even though it's similar to pottery from other areas. Five main themes are seen in this style:

- The winged serpent: A creature with a rattlesnake body, feathered wings, a mammal head, and deer antlers. It's a local version of the Horned Serpent.

- The crested bird: Two woodpecker-like birds with long necks and crests tied in knots around a central design.

- The raptor: A bird of prey with a hooked beak and a jagged crest, similar to falcon and eagle designs.

- Center symbols and bands: A central symbol (like a cross-and-circle or swastika) with geometric bands reaching out. These designs might be linked to the four directions of the universe.

- Trophy theme: Designs that combine skulls, human hands, arm bones, and scalps. These might represent the journey of the dead into the afterlife.

The Hemphill style pottery was made mostly in the 1300s and early 1400s CE. It's thought that only a few potters made these pieces at any one time. The best pieces were made in the 1300s and show influences from other cultures. Later pieces from the 1400s show less skill, which might mean this art form became less important.

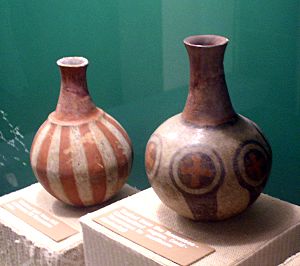

Moundville Painted Pottery

Many painted pots have also been found at Moundville. They look like pottery from the Tennessee, Cumberland, lower Ohio River, and central Mississippi Valleys. For a long time, people thought these pots were all brought in through trade. Modern tests show that many were indeed traded, but some were also made locally at Moundville.

These painted pots have designs in red, white, and black. The red and white were colored clay slips. The black was made from carbon using a "negative" or "resist" technique. Like the engraved pots, these painted ones have thin walls, shell temper, and a polished outside. They come in two main shapes: a bottle with a round body and a narrow, curved neck, and a special rectangular bowl unique to Moundville. This rectangular bowl has straight sides, a flat bottom, and an unusual rim where one side is lower than the others. The designs on these rectangular pots are similar to other local designs, including symbols like the cross-in-circle (thought to be a scalp on a hoop), the hand, the skull, and spirals.

Southern Appalachian Pottery

Pottery has helped archaeologists understand the timeline of Southern Appalachian Mississippian cultures. At first, Limestone was used as temper, but then shell became popular. Round bowls and jars were common, sometimes with decorated rims and handles. Salt pans, platters, bottles, and effigies were also found. Coarse, cord-marked pots were for cooking, while fine, polished pots were for serving.

In the Piedmont and Blue Ridge areas, potters used crushed quartz crystal and grit as temper. Pots from the Pisgah phase in Western North Carolina used sand. These pots didn't have rim lugs or handles. Their surfaces were either plain or decorated with "Complicated Stamped" designs. These designs were pressed into unfired clay using wooden or pottery paddles. Many stamps were found at Nacoochee Mound in Georgia. Across the Southeast, you can find "negative pottery" with dark circles, crosses, and rings on lighter backgrounds.

-

Pottery from the Fort Walton Culture

-

Human effigy from Ocmulgee in Georgia

Pottery in Archaeology

Studying pottery is super important for archaeologists to figure out the dates of Mississippian cultures. Since pottery is strong and lasts a long time (unlike things made from wood or cloth), it's often one of the few objects found in large numbers. Along with stone tools, pottery helps archaeologists understand how these societies were organized, how they traded, and how their culture developed.

Even though most Mississippian pottery was for everyday use, the fancier pieces were likely made for trade or special ceremonies. By studying this pottery, we can learn about their daily lives, their beliefs, their social groups, and their connections with other communities.

Protecting Ancient Sites

When Europeans first came to the rich river valleys of the Midwest and Southeast, they found abandoned villages and large mounds left by the Mississippian people. Sadly, many of these sites were destroyed for farming or dug up by people looking for treasure.

As the value of these ancient pots grew, some people started digging up sites just to sell the artifacts. This is called looting. Today, many states and the U.S. government have laws against looting archaeological sites. However, because these objects can be sold for high prices on the black market, these laws are sometimes ignored.

Two well-known examples of looted sites are the Spiro Mounds site in Oklahoma and the Slack Farm site in Kentucky. At Spiro, a company was even formed to dig up the site. Over a few years, many delicate items were destroyed as looters used dynamite to get into the main burial mound in 1934. This destruction helped push for laws to protect American archaeological sites.

In 1987, ten people paid money to dig at the Slack Farm property. After two months, local complaints led to their arrest for damaging a historical site. This event helped lead to new laws, like the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, which made it clearer that such activities were illegal. When objects are removed secretly and not recorded, it destroys their archaeological value. The location where an object is found, how deep it was buried, what was around it, and its original condition are all important clues for understanding history. All this information is lost when an object is looted and sold.

|

| Calvin Brent |

| Walter T. Bailey |

| Martha Cassell Thompson |

| Alberta Jeannette Cassell |