Parkin Archeological State Park facts for kids

|

Parkin Indian Mound

|

|

Artist's conception of the archaeological site

|

|

| Nearest city | Parkin, Arkansas |

|---|---|

| NRHP reference No. | 66000200 |

Quick facts for kids Significant dates |

|

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1966 |

| Designated NHL | July 19, 1964 |

Parkin Archeological State Park, also known as Parkin Indian Mound, is a special place in Parkin, Cross County, Arkansas. It's an archeological site, which means scientists study old things found here. Long ago, between about 1350 and 1650 CE, an Native American village stood here. This village was surrounded by a strong wooden fence called a palisade. It was built where the St. Francis and Tyronza rivers meet.

You can see many old tools and items, called artifacts, from this village at the site's museum. The Parkin site is very important because it helps us understand the "Parkin phase" of the Mississippian culture. This was a group of people who lived in the area during the Late Mississippian period. Many experts think this site was part of a place called Casqui. The Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto visited Casqui in 1542. The artifacts found here show that people lived in the Parkin village from about 1400 to 1650 CE.

Because of its importance to understanding the Parkin phase, the Parkin site was named a National Historic Landmark in 1964. Then, in 1966, it was added to the National Register of Historic Places. You can find Parkin Archeological State Park at 60 Arkansas Highway 184 North, Parkin, Arkansas.

Contents

Life in the Parkin Phase

The Parkin site is key to understanding a group of people called the Parkin phase. They were part of the Mississippian culture and lived from about 1400 to 1700 CE. The Parkin phase included many villages along the St. Francis and Tyronza rivers. These people lived at the same time as other groups like the Caborn-Welborn and Nodena phases. It seems people lived at the Parkin site for at least 500 years without leaving.

In the early 1540s, the Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto and his team likely visited several Parkin phase villages. Historians believe the Parkin phase was the "Province of Casqui" that De Soto wrote about. Another nearby group, the Nodena phase, is thought to be the province of Pacaha.

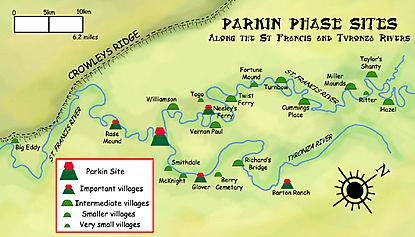

De Soto's records say that these areas were ruled by powerful chiefs. Each chief lived in a main town and had smaller towns around it that followed his rules. The Parkin phase had about twenty-one villages of different sizes. They were spread out along the St. Francis and Tyronza rivers, usually about 2.5 miles (4 km) apart. Some of these villages were Rose Mound, Glover, Neeleys Ferry, and Barton Ranch.

How Villages Were Set Up

Long ago, people lived in small homes and tiny villages. But over time, fighting became common. This made people move together into bigger villages surrounded by strong wooden fences called palisades. During the day, they would leave their villages to farm, gather wood, and hunt. But at night, they would return to the safety of their well-protected homes.

The people of the Parkin phase were somewhat separated from other groups. To their east and southeast were large swamps. The Spanish explorers said these swamps were very hard to cross. These wet areas acted like natural walls, keeping different groups apart and safe from enemies.

Over time, the Parkin phase people developed their own unique way of life. This included special designs on their pottery and different ways of burying their dead. These changes show that they became more distinct from their neighbors. They were part of a large religious and trade network called the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex. Through this network, they got special items like Mill Creek chert (a type of stone) and whelk shells.

Farming and Food

The people of Parkin were very good at maize (corn) farming. They also grew other important foods that came from the Americas. These included beans, gourds, squash, and sunflowers. Women usually managed the farming and prepared the food. They even developed different kinds of corn and vegetables. After harvest, corn was stored in large bins above the ground to be eaten later. Women also collected wild foods like pecans and persimmons.

De Soto's explorers wrote that the area was heavily farmed. They said it was the most crowded place they had seen in "La Florida." They also mentioned groves of wild fruit and nut trees. This suggests the Parkin people kept these trees while clearing others for their crops. Men hunted animals like deer, squirrel, rabbit, turkey, and mallard ducks. They also fished for alligator gar, catfish, drum fish, turtles, and mussels. The two rivers and the village moat were excellent places to catch fish. De Soto's team often received "gifts of fish" from the people of Casqui.

What Language Did They Speak?

The people of Parkin likely spoke a Tunican or Siouan language. We know that Tunica-speaking people lived in this area when De Soto arrived. Other related groups in the region might have also been Tunica speakers. To their west and south, people probably spoke Caddoan languages. Later, by the 1670s, the Quapaw people lived in this area. They spoke a Dhegiha Siouan language. Scientists have tried to connect the pottery styles and words from De Soto's stories to the Quapaw, but it has been difficult.

The Parkin Village: 1350–1650 CE

The Parkin site was a 17-acre (6.9 ha) village surrounded by a palisade. It was built where the St. Francis and Tyronza rivers meet. All other villages of the Parkin phase were on very rich soil. However, the Parkin site's soil was not good enough to feed all the people who lived there. It's believed the large village was placed at the river meeting point to control river travel and trade.

The village had one large main mound and six smaller mounds. These mounds were arranged around a central open space called a plaza. The largest mound was 21.3 feet (6.5 m) tall. It had a lower, flat area that was 5 feet (1.5 m) tall. This main mound was next to the St. Francis River, with the plaza on its other side. Spanish explorers said the chief, Casqui, lived in a big house on top of this main mound. His wives and helpers lived in homes on the lower, flat part of the mound.

The other six mounds were smaller, ranging from 3.2 to 5 feet (1 to 1.5 m) tall. The plaza was used for important religious events and games. People played games like chunkey and a ballgame there. Around the plaza were many well-organized houses. They were lined up with the mound and plaza, showing the village was carefully planned. The Spanish said these villages had few trees. This was probably because wood was used for fuel and building. The Spanish camped in a nearby group of trees to escape the heat. Homes were made from wattle and daub (a mix of mud and sticks) with thatched roofs.

A strong wooden fence, or palisade, surrounded the village on three sides for defense. It had towers, called bastions, at regular spots. These towers had openings for archers to shoot arrows at enemies. Just outside the palisade was a wide moat (a ditch filled with water). This moat surrounded the village on three sides and connected to the St. Francis River, which formed the fourth side. The land inside the ditch and palisade was about 3.2 feet (1 m) higher than the land around it. This might have been built up by the villagers, or it could have grown higher over time from dirt and trash building up.

Pottery Styles

Most pottery found at the Parkin site is simple, everyday pottery. It's known as Mississippian Plain var. Neeleys Ferry and Barton Incised var. Togo. This pottery was mostly for daily use, not the fancy burial pots found at other sites like Nodena. An archaeologist named Clarence Bloomfield Moore once described pottery from this area as "lopsided" and "not well made."

However, some very detailed pots have also been found. These include pots shaped like human heads, underwater panthers, fish, and dogs. There are also red and white bottles with spiral or swastika designs. The fact that simpler pots were often buried with people seems to be a cultural difference for the Parkin people.

Like other groups in the area, the Parkin people often placed a bowl and a bottle in graves. Parkin pottery was made by building up strips of clay, then smoothing them. This was a common method in Eastern America, as the potters wheel was not known there. Potters used natural colors like galena for white, hematite for red, and sometimes graphite for black to paint their pottery. The pots shaped like human heads give us an idea of what the people of Parkin might have looked like. You can see a bust based on these pots at the Parkin site museum.

Spanish Items Found Here

In 1966, a Spanish trade bead was found at the Parkin site. This bead matches descriptions of the special seven-layer glass beads that De Soto's expedition carried. A brass bell, called a "Clarksdale bell," was also found. This bell was buried with a child, along with four pottery items that are typical of the Parkin phase. This is one of the few places in the Southeast where items from De Soto's journey have been found in a way that helps scientists date them.

In 1977, a large charred posthole was discovered at the top of the main mound. In 2016, a piece of a cypress log was found. Many believe this log might be part of the tall cross that De Soto put up at the site in 1541. Scientists were still studying this log in April 2016.

See also

| William Lucy |

| Charles Hayes |

| Cleveland Robinson |