Tunica people facts for kids

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| United States (Mississippi, Arkansas, Louisiana) | |

| Languages | |

| Tunica language (isolate) | |

| Religion | |

| Native tribal religion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Yazoo, Koroa, Tioux |

The Tunica people are Native American tribes who share similar languages and cultures. They lived in the Mississippi River Valley. The main groups include the Tunica (also called Tonica or Tonnica), the Yazoo, the Koroa, and possibly the Tioux.

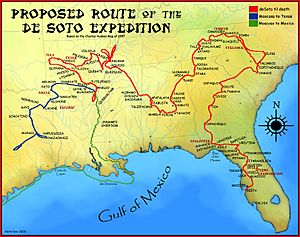

The Tunica people first met Europeans in 1541. These Europeans were part of the Hernando de Soto expedition. The Tunica language is special because it is a "language isolate." This means it's not clearly related to any other known language family.

Over many years, the Tunica moved south. They were under pressure from other tribes. They traveled from the Central Mississippi Valley to the Lower Mississippi Valley. Eventually, they settled near what is now Marksville, Louisiana.

Since the early 1800s, the Tunica have married people from the Biloxi tribe. The Biloxi are a different group from near Biloxi, Mississippi. They speak a Siouan language. The Tunica and Biloxi shared land and their lives. Other small tribes also joined them over time.

In 1981, the United States government officially recognized them as a tribe. They are now called the Tunica-Biloxi Indian Tribe. They have a special area of land called a reservation in Avoyelles Parish, Louisiana.

Contents

Ancient Tunica People: Before Europeans Arrived

Life in the Mississippi Valley

Around 1000 to 1500 AD, people in the Central Mississippi Valley lived a "Mississippian lifestyle." This means they grew a lot of maize (corn). They also had leaders and organized societies. Their pottery was often made with crushed mussel shells. They were part of a large cultural network called the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex.

At first, people lived in small groups, farms, and villages. Later, towns became more important. These towns often had strong walls and ditches for defense. This shows that different groups were often fighting each other. Their pottery styles and burial customs also started to become different.

Powerful Chiefdoms and Their Lands

Archaeologists study old sites to learn about these groups. They believe the Mississippi Valley had several powerful chiefdoms. These were like small kingdoms with a main leader. Smaller groups often supported them. These groups are identified by archaeologists as "phases." This is based on their unique tools and pottery.

Some important phases include Menard, Tipton, Belle Meade-Walls, Parkin, and Nodena. Near modern-day Memphis, Tennessee, the Parkin and Nodena groups were very powerful. Other groups might have been their allies or under their control.

The Parkin group was centered at the Parkin site. This was a large village with walls, covering about 17 acres. It was located where the St. Francis and Tyronza rivers meet. This spot was good for controlling trade and travel on the rivers.

The Nodena group was likely centered around the Bradley Site. It included many towns and villages. The most famous site is the Nodena site, located in Mississippi County. It was on a bend of the Mississippi River. Experts think the Belle Meade and Walls groups were allies of Nodena. The Parkin group, with different customs, was a rival.

First Meetings: Spanish Explorers Arrive

De Soto's Expedition and the Quizquiz People

In the spring of 1541, Hernando de Soto and his army reached the Mississippi River. They found a place called the Province of Quizquiz. The people here spoke a language related to Tunica. These groups lived on both sides of the Mississippi River in what is now Mississippi and Arkansas.

De Soto's men were surprised by the Quizquiz people. They found the men working in cornfields. The Spanish took many women and goods from their homes. The chief of Quizquiz was old and sick. But he bravely tried to defend his village. He was very angry that strangers had entered his land without permission.

Meeting Other Tribes and Trading Salt

After crossing the river, the Spanish met the Aquixo and then the Casqui people. The Casqui had a long-standing fight with the Pacaha people. The Spanish were very impressed by the towns in this area. They had strong walls and ditches, some filled with water and fish. The people were also described as very good.

The expedition later visited other places like Quigate, Coligua, and Palisema. The chief of Palisema sent them to the land of the Cayas, where they found a town called Tanico. Experts believe the Coligua were the Koroa tribe. The Tanico people were known for making and trading salt. They got salt from river sands. This was a very valuable item for trade.

Archaeologists and historians have studied the Spanish stories and old sites. They believe many groups in the Central Mississippi Valley were Tunican. This includes people from Pacaha in the north to Anilco in the south. The words recorded by the Spanish at Pacaha also match Tunica language features.

Changes After Spanish Contact

It took 150 years for another European group, the French, to meet the Tunica. By 1699, the Tunica were a smaller tribe, with only about 900 people. The Spanish visit, though short, had a huge impact. European diseases like smallpox spread. Native people had no protection against these illnesses. Also, the Spanish sometimes made local tribes fight each other.

By the time the French arrived, the Central Mississippi Valley had fewer people. The Quapaw tribe, who spoke a different language, lived there and were not friendly with the Tunica. The Tunica and Koroa had moved south to the mouth of the Yazoo River in Mississippi.

Tunica History: From French Contact to Today

Life at the Yazoo River (1682–1706)

The French set up a mission among the Tunica around 1700. This was near the Yazoo River in Mississippi. Evidence shows the Tunica had recently moved there from eastern Arkansas. A missionary named Father Antoine Davion worked with the Tunica and smaller tribes.

Unlike some northern tribes, the Tunica had a complex religion. They built temples and had priests. The Tunica, along with the Taensa and Natchez, kept some old chiefdom traditions. This included complex religious practices.

The Tunica were known for their farming, with men doing much of the work. They were also important traders. Their salt trade was very old, as de Soto had noted. Salt was key for trade between the French and other Native American groups. The Tunica acted as middlemen, helping move salt from western areas to the French.

Moving to Angola (1706–1731)

In the early 1700s, the Chickasaw tribe raided other tribes to capture people for the slave trade. They took many Tunica, Taensa, and Quapaw people. Because of these attacks, the Tunica decided to move again in 1706.

They moved across the Mississippi River and south to where it meets the Red River. This new location helped them keep control of their salt trade. The Red River also connected to their salt sources. They built several small villages in what is now Angola, Louisiana.

Later, in 1967, an officer at the Louisiana State Penitentiary (which is now in Angola) found remains of a small village. This place is now known as the Bloodhound Site.

The Natchez Rebellion and Tunica Bravery

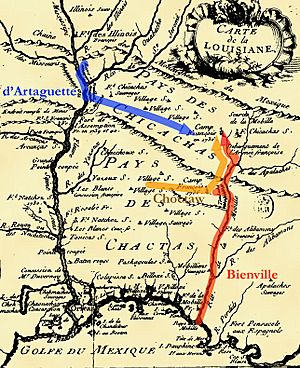

Between 1710 and 1729, the French and Natchez tribes fought several wars. The last one was the Natchez Rebellion of 1729. The Natchez attacked and killed many French people. The French, with help from the Choctaw, eventually defeated the Natchez. Many Natchez survivors were sold into slavery.

The Yazoo and Koroa tribes had joined the Natchez and suffered the same fate. The Tunica at first did not want to pick a side. In June 1730, the Tunica Head Chief, Cahura-Joligo, allowed some Natchez refugees to settle near his village. He made them give up their weapons.

A few days later, more Natchez arrived with other tribes hiding nearby. Cahura-Joligo asked them to give up their weapons too. They agreed but asked to keep them a bit longer. He let them. After a celebration, the Tunica went to sleep. The Natchez and their allies then attacked the Tunica in their homes.

Cahura-Joligo bravely fought and killed four Natchez, but he was killed along with twelve of his warriors. His war-chief, Brides les Boeufs (Buffalo Tamer), fought back. He and his warriors fought for five days and nights. They regained control of the village. Twenty Tunica were killed, and many were wounded. They killed 33 Natchez warriors and captured three. The Tunica then burned the prisoners as a punishment for the attack.

Life at Trudeau Landing (1731–1764)

After the attack at Angola, the Tunica moved a few miles to the Trudeau Landing site in West Feliciana Parish in 1731. Here, the Tunica continued to do well as traders. They also started a new business: trading horses. The French relied on the Tunica for these valuable animals.

A French visitor described meeting Chief Cahura-Joligo in 1721. He said the chief was dressed in French clothes and was very polite. He was highly respected by French leaders. The chief traded horses and chickens with the French. He was also very good at saving money.

Horses were expensive to ship from France. So, the French found it cheaper to buy them from the Tunica in Louisiana. The Tunica got these horses through a trade network that reached all the way to Mexico. The Tunica stayed at Trudeau Landing until the 1760s. This was when the French gave control of Louisiana to the Spanish after losing the Seven Years' War.

In the 1960s, the Trudeau site was found and dug up by archaeologists. They found many European trade goods. These included beads, porcelain, guns, and kettles. They also found Tunica pottery. These items were buried with people as grave goods. This collection, called the "Trudeau Treasure," showed how rich the tribe was during this time.

Moving to Pointe Coupee and Marksville (1764–Present)

In 1764, the Tunica moved about 15 miles south to Pointe Coupée. Other tribes, like the Offagoula, Pascagoula, and Biloxi, also settled there. The Biloxi, who spoke a Siouan language, became very close to the Tunica. Over many years, they married each other. In 1981, they were officially recognized as the Tunica-Biloxi Nation of Louisiana.

The Tunica started to hunt more for food. They also worked for Europeans as hunters or guides. In the late 1700s, many American settlers moved into the area. The Tunica had adopted some European ways. But they still kept their tattooing and some religious customs. Their Head Chief was Lattanash, and Brides les Boefs was still the War Chief. The Ofo people had mostly joined the Tunica by this time.

The Tunica moved west again in the late 1700s or early 1800s. They settled on the Red River, on land given to them by the Spanish. Other tribes like the Ofo and Biloxi also settled there. In 1794, a trader named Marco Litche started a trading post. This settlement grew into Marksville, Louisiana.

By the late 1800s, railroads became more important than rivers for travel. Marksville became a quiet place. Many small, peaceful tribes like the Tunica were often overlooked. In 1806, a U.S. official noted that the Tunica had about 25 men. They lived in Avoyelles Parish and sometimes worked as boatmen.

Problems with white neighbors grew. In 1841, the Tunica chief Melancon tried to remove a fence that an American had put on Tunica land. The American, a local leader, shot Chief Melancon in the head. He was not punished, and he stole the land. After this, the tribe kept the identity of their next chief a secret for many years.

The Tunica became farmers, hunters, and fishers. Some worked as sharecroppers on white neighbors' lands. In the 1870s, Chief Volsin Chiki helped bring the tribe back together. He also encouraged old tribal ceremonies, like the Corn Feast.

As the 1900s began, the Tunica continued. They had managed to keep most of their land because the whole tribe owned and worked it together. Some still spoke the Tunica language. Their tribal ceremonies were strong again. Over time, the Tunica joined with and absorbed other local groups. The Tunica-Biloxi finally received federal recognition in 1981.

The Tunica-Biloxi Tribe Today

Modern Life and Government

The modern "Tunica-Biloxi Indian Tribe" lives in Mississippi and east-central Louisiana. The tribe includes people of Tunica, Biloxi, Ofo, Avoyel, Mississippi Choctaw, European, and African backgrounds. Many live on the Tunica-Biloxi Indian Reservation in Avoyelles Parish, near Marksville, Louisiana. Part of Marksville is on the reservation land. The reservation covers about 1.682 square kilometers (0.65 square miles).

The tribe runs Louisiana's first land-based casino, the Paragon Casino Resort. It opened in Marksville in 1994. The casino helps the tribe earn money for its members and for other projects. It also helps them fight for Native American rights. In 2000, 648 people said they were Tunica.

The tribe has an elected tribal council and a tribal chairman. They have their own police force, health services, education department, housing authority, and court system. Earl J. Barbry, Sr. was the tribal chairman from 1978. The current Chairman of the Tribal Council is Marshall Pierite.

The Tunica Treasure

In the 1960s, a treasure hunter started looking for old items at the Trudeau Landing site. The Tunica people were very upset. They felt he was stealing their family treasures and disturbing their ancestors' graves. In the 1970s, archaeologists dug up the site. They found pottery, European trade goods, and other items. These were buried with Tunica people between 1731 and 1764.

With help from Louisiana, the tribe sued to get the items back. This case became known as the "Tunica Treasure." It took ten years in court. The ruling was a big step for Native American rights. It helped create a new federal law in 1990, the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act. Since the items were already separated from the burials, the tribe decided to build a museum for them. Tribe members were trained to repair and care for the items.

From 1991 to 1999, the Tunica built a museum shaped like their ancient platform mounds. This building was a symbolic burial place for the items. Later, the collection moved to a new building. This new building has a museum, a lab for caring for items, and offices for the tribal government.

Official Recognition

The tribe started working to be recognized by the U.S. government in the 1940s. Chief Eli Barbry led a group to Washington, D.C.. Federal recognition would help the tribe get benefits from programs like the Indian Reorganization Act. Several chiefs worked on this goal. The Tunica Treasure was important proof of the tribe's long history. In 1981, the United States government officially recognized them as the Tunica-Biloxi Indians of Louisiana.

Tunica Language

The Tunica language (also called Tonica or Yuron) is a language isolate. This means it is not related to any other known language. The last person who spoke Tunica as their first language, Sesostrie Youchigant, died in 1948. A linguist named Mary Haas worked with him in the 1930s. She wrote books about the language, including a grammar, texts, and a dictionary.

The Tunica tribe lived near the Ofo and Avoyeles tribes. But they could only talk to each other using a trade language called Mobilian Jargon or French. Most modern Tunica people speak English. Some older members speak French as their first language. Today, the Tunica language is taught in weekly classes, special programs, and a summer camp for young people.

See also

In Spanish: Tunica para niños

In Spanish: Tunica para niños

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |