Tunica-Biloxi facts for kids

| Yoroniku-Halayihku | |

|---|---|

Tribal Flag

|

|

| Total population | |

| 951 (2010 Census) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| English, French Formerly Tunica, Biloxi |

|

| Religion | |

| Protestantism, Roman Catholicism, traditional religion |

|

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Biloxi and Tunica peoples |

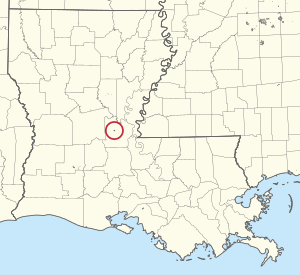

The Tunica-Biloxi Indian Tribe, also called Yoroniku-Halayihku in their native language, is a federally recognized tribe. This means the United States government officially recognizes them as a Native American tribe. They are mainly made up of Tunica and Biloxi people. You can find them in east central Louisiana.

Other groups like the Ofo (who spoke a Siouan language), Avoyel (related to the Natchez people), and Choctaw people are also part of the tribe. Today, most tribal members speak English and French. Many live on the Tunica-Biloxi Indian Reservation (31°06′48″N 92°03′13″W / 31.11333°N 92.05361°W). This reservation is in central Avoyelles Parish, just south of Marksville, Louisiana. The reservation covers about 1.682 km2 (0.649 sq mi).

In 2010, the census showed that 951 people said they were at least partly Tunica-Biloxi. Out of those, 669 identified as only Tunica-Biloxi.

Contents

History of the Tunica-Biloxi People

Long ago, during the Middle Mississippian period, people in the Central Mississippi Valley lived a special way of life. They grew maize (corn), had leaders with power, made pottery with mussel shells, and took part in the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex (SECC). This was a network of shared beliefs and art.

Archaeologists believe that several powerful groups, called chiefdoms, lived in the valley. These groups often had smaller, supporting communities. Experts have named these groups after different archaeological phases, like Menard, Tipton, Walls, Parkin, and Nodena.

First European Encounters

In the spring of 1541, a Spanish explorer named Hernando de Soto and his army arrived at the Mississippi River. They found a group called the Quizquiz (pronounced "keys-key"). These people spoke a language called Tunica, which is unique and not related to many other languages. De Soto's group soon learned that these related Tunica-speaking groups lived across a large area on both sides of the Mississippi River. This area is now parts of Mississippi and Arkansas.

The chief's home was on a tall mound, like a fortress. You could only reach it by two stairways. The old and sick chief, also named Quizquiz, heard the noise in his village. He got up and grabbed a battle-ax. He angrily walked down the stairs, vowing to fight anyone who entered his land without permission. His memories of brave acts and victories from his younger days gave him strength to make these fierce threats.

—Inca Garcilaso de la Vega describing the Quizquiz, 1605

Experts have studied de Soto's stories and archaeological finds. They believe the Menard, Walls, Belle Meade, Parkin, and Nodena sites match the provinces de Soto named: Anilco, Quizquiz, Aquixo, Casqui, and Pacaha.

It was 150 years before Europeans wrote about the Tunica again. In 1699, the LaSource expedition from French Canada met the Tunica. They described them as a small tribe with only a few hundred warriors. The Tunica and other groups had suffered from smallpox epidemics. This new disease, brought by Europeans, caused many deaths because Native Americans had no natural protection against it.

By the time the French arrived, the Central Mississippi Valley had few people living there, mostly the Quapaw. The Quapaw became important friends to the French and helped them settle successfully. Around 1700, the French set up a mission among the Tunica near the Yazoo River. A priest named Father Antoine Davion worked with the Tunica and smaller tribes like the Koroa, Yazoo, and Houspé.

Skilled Traders

The Tunica were very good at trading. They were especially known for making and selling salt. Salt was very important for trade between the French and the various Caddoan groups in what is now northwestern Louisiana and southwestern Arkansas. The Tunica were likely the main traders who brought salt from the Caddoan areas to the French.

In the early 1700s, tribes along the lower Mississippi River were often attacked by the Chickasaw. The Chickasaw were capturing people to sell to the English in South Carolina. Because of these dangers, the Tunica decided to move in 1706.

They moved to the Mississippi side of the Mississippi and Red River where the two rivers meet. This allowed them to keep control of their salt trade, as the Red River connected to their salt source. They built a group of small villages near what is now Angola, Louisiana. In 1976, a small village from this time was found by an inmate at Angola Prison. It is called the Bloodhound Site.

Conflicts and Moves

During the 1710s and 1720s, the French and the Natchez often fought. The biggest fight was the Natchez Massacre in 1729. The Natchez killed most of the French at the village of Natchez and Fort Rosalie. French colonists, with help from their Native American allies, fought back. They killed or captured most of the Natchez survivors, who were then sold into slavery.

In 1729, the Natchez leaders asked other tribes for help, including the Yazoo, Koroa, Illinois, Chickasaw, and Choctaw. The Natchez Rebellion became a larger conflict with many effects. The Tunica at first did not want to pick a side.

In June 1730, the Tunica Head Chief, Cahura-Joligo, allowed a small group of Natchez refugees to settle near his village (Angola). He said they must be unarmed. A few days later, the Natchez chief arrived with a hundred men and many women and children. They had hidden Chickasaw and Koroa warriors in the tall grass around the village. Cahura-Joligo told the Natchez they could not stay unless they gave up their weapons. They said they would, but asked to keep their weapons a bit longer. He agreed and gave them food. A dance was held that night.

After the dance, when the village was asleep, the Natchez, Chickasaw, and Koroa attacked. Cahura-Joligo killed four Natchez but was killed along with 12 of his warriors. His war-chief, Brides les Boeufs (Buffalo Tamer), fought back. He gathered the warriors, and after five days and nights of fighting, they took back control of the village. Twenty Tunica were killed and many were hurt. They killed 33 Natchez warriors.

After this attack, in 1731, the Tunica moved a few miles away to the Trudeau site. Over the years, they buried many European trade goods with their dead. These included beads, porcelain, muskets, and kettles, along with their own pottery. When these items were found in the 1900s, they showed how much the Tunica traded with Europeans and how wealthy they were.

They lived at this site until the 1760s. At that time, the French gave control of the land west of the Mississippi to the Spanish. This happened after the French lost to the British in the Seven Years' War.

In 1764, the Tunica moved 15 miles (24 km) south of Trudeau Landing. They settled near the French town of Pointe Coupée, Louisiana. Other tribes, like the Offagoula, Pascagoula, and Biloxi, also settled there. The Biloxi became very close to the Tunica. During this time, many Anglo-American settlers moved into the area. The British had taken over French lands east of the Mississippi.

The Tunica had adopted some European ways, but they still tattooed themselves and kept some of their native religious customs. The area was politically unstable, with the British in charge of West Florida and the Spanish controlling Louisiana. In 1779, Governor Galvez led a force, including Tunica and other tribal warriors, to take the British town of Baton Rouge. This was the last time the Tunica were recorded fighting in a military campaign.

By the late 1780s or 1790s, the Tunica moved again. This was likely because many Anglo-Americans were moving into the area. They moved west to a place on the Red River called Avoyelles. In 1794, a Jewish trader from Venice named Marco Litche (also known as Marc Eliche) set up a trading post there. A European-American settlement grew around this post and became known as Marksville. It appeared on Louisiana maps by 1809.

Life After the US Acquired Louisiana

Marksville was a good place for a trading post because the Red River was still important for trade. But things changed quickly. In 1800, France, led by Napoleon Bonaparte, took back the area. After losing control of its colony in Saint-Domingue, France sold the huge territory known as the Louisiana Purchase to the young United States in 1803.

Many Anglo-Americans, mostly from the southern United States, moved to Louisiana. Over time, they changed the culture to one mostly speaking English and practicing Protestant Christianity. This was especially true in the northern parts of the area. In the late 1800s, railroads became more important than rivers for trade and travel. The Marksville area became a quiet, less busy place.

From 1803 to 1938, the only US government mention of the Tunica was in 1806. An Indian Commissioner for Louisiana noted that only about 25 Tunica men lived in Avoyelles Parish. They earned money by sometimes working as boatmen. Even though the Tunica were doing well then, problems with their white neighbors eventually caused difficulties.

White settlers created a social system based on slavery and race. They only recognized whites and blacks, and often ignored Native American identity among people of mixed heritage. They did not understand that these people still saw themselves as Tunica. By the late 1800s, powerful white leaders created laws to separate people by race. They also took away voting rights from black people and other minorities. The Tunica became farmers who grew just enough food for themselves. Some also hunted and fished. Others became sharecroppers on their white neighbors' land.

As the 1900s began, the Tunica people came together around their old traditions. They had managed to keep most of their shared land. Some still spoke the Tunica language, and they continued to practice their tribal ceremonies.

The Tunica-Biloxi in the 20th Century and Today

Over time, the remaining members of other local tribes, like the Ofo, Avoyel, Choctaw, and Biloxi, joined the Tunica. The tribe has kept much of its unique identity. They kept their tribal government and a system of hereditary chiefs until the mid-1970s.

The modern Tunica-Biloxi tribe has a written constitution and an elected government. The federal government officially recognized them in 1981. They live in Mississippi and east central Louisiana. The modern tribe includes Tunica, Biloxi (a Siouan-speaking group), Ofo (also Siouan), Avoyel (a Natchezan group), and Mississippi Choctaw. Many live on the Tunica-Biloxi Indian Reservation in central Avoyelles Parish, just south of Marksville, Louisiana. Part of Marksville is on reservation land.

The reservation covers 1.682 km2 (0.649 sq mi). The tribe runs Louisiana's first land-based casino, Paragon Casino Resort. It opened in Marksville in June 1994. The 2000 census showed 648 people identified as Tunica.

Today, the tribal government has an elected tribal council and a tribal chairman. The tribe has its own police force, health services, education department, housing authority, and court system. Earl J. Barbry, Sr., was a tribal chairman for a very long time, from 1978 until his death in 2013. Marshall Pierite became chairman in 2013, then Joey Barbry in 2014, and Marshall Pierite was elected chairman again in 2018.

The Tunica Treasure

In the 1960s, a treasure hunter named Leonard Charrier started looking for old items at the Trudeau Landing site in West Feliciana Parish, Louisiana. The Tunica people were very upset. They felt he had stolen tribal heirlooms and disturbed the graves of their ancestors.

In the 1970s, archaeologists dug at the site. They found many pieces of pottery, European trade goods, and other artifacts. These items were buried with the Tunica people between 1731 and 1764, when they lived at the site. With help from the State of Louisiana, the tribe went to court to get ownership of these items, which became known as the "Tunica treasure."

The court case took ten years, but the decision was a big step for Native American history. It helped create a new federal law called the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), passed in 1990. This law helps protect Native American graves and gives tribes the right to get back cultural items.

Because the artifacts had been separated from their original burials, the tribe decided to build a museum to keep them. Tribal members were trained as conservators to fix damage to the artifacts. The museum was built to look like the ancient temple mounds of their people. It opened in 1989 as The Tunica-Biloxi Regional Indian Center and Museum. It closed in 1999 due to building problems.

Today, the Tunica Treasure collection is in the Tunica-Biloxi Cultural and Educational Resources Center. This modern building includes a library, a conservation center, and a museum on the tribal reservation in Marksville. Eighty percent of the Tunica Treasure artifacts have been restored.

Becoming Federally Recognized

The tribe began trying to get federal recognition in the 1940s. Chief Eli Barbry, Horace Pierite, Clarence Jackson, and Sam Barbry traveled to Washington, D.C. to talk with the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Federal recognition would have allowed the tribe to get help from social programs under the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934. Many chiefs, including Chief Horace Pierite Sr., worked on this goal.

The discovery of the Tunica treasure helped prove their ancient tribal identity. The tribe gained state and federal recognition in 1981. They were first recognized as the Tunica Biloxi Indians of Louisiana, and later changed their name to Tunica-Biloxi Indian Tribe.

Economic Growth

The Tunica-Biloxi Tribe runs Louisiana's first land-based casino, Paragon Casino Resort. It opened in Marksville in June 1994. Today, it is the largest employer in Avoyelles Parish.

The Tribe also owns and runs an online installment loan company called Mobiloans. They also have a film finance and production company called Acacia Entertainment. Acacia Entertainment works with film producer Matthew George to make two to three films each year.

Tunica and Biloxi Languages

The Tunica language (also called Tonica or Yuron) is a language isolate. This means it is not closely related to any other known language. The Tunica tribe historically lived near the Ofo and Avoyeles tribes. However, they used Mobilian Jargon or French to talk with each other.

The last known person who spoke Tunica as their first language, Sesostrie Youchigant, died in 1948. A linguist named Mary Haas worked with Youchigant in the 1930s to record what he remembered of the language. She published a book about Tunica grammar in 1941, followed by Tunica texts in 1950, and a Tunica dictionary in 1953. Tunica is now a "reawakening language." This means there are programs and summer camps teaching it to new learners.

The Biloxi language is a Siouan language. It was once spoken by the Biloxi people in Louisiana and southeast Texas. Europeans first wrote about the Biloxi living along the Biloxi Bay in the mid-1600s. By the mid-1700s, they had moved into Louisiana to avoid European settlement. Some were also noted in Texas in the early 1800s. By the early 1800s, their numbers had become very small. In 1934, the last native speaker, Emma Jackson, was in her 80s.

Most modern Tunica-Biloxi people speak English. A few older members still speak French as their first language.

Notable Tunica-Biloxi People

- Earl Barbry, a Native American leader and former chairman of the Tunica-Biloxi Tribe.

- Allen Barbre, an American football player who played as an offensive tackle for the Denver Broncos.

- Chief Sesostrie Youchigant, a former chief of the Tunica-Biloxi tribe and the last person to speak Tunica as his first language. He shared his knowledge of the language with researchers.

Images for kids

| Ernest Everett Just |

| Mary Jackson |

| Emmett Chappelle |

| Marie Maynard Daly |