Narváez expedition facts for kids

The Narváez expedition was a Spanish journey of exploration and colonization that began in 1527. Its goal was to set up new settlements and forts in Florida. Pánfilo de Narváez led the expedition at first, but he died in 1528. Many more people died as the group traveled west along the Gulf Coast of what is now the United States.

Only four of the original members survived this difficult journey. They reached Mexico City in 1536. These survivors were the first non-Native Americans known to see the Mississippi River. They were also the first to cross the Gulf of Mexico and Texas.

Narváez started with about 600 people, including men from Spain, Portugal, Greece, and Italy. The expedition faced problems almost right away. On their way to Florida, their ships stopped in Hispaniola and Cuba. A powerful hurricane and other storms badly damaged the fleet, and they lost two ships.

They left Cuba in February 1528. Their plan was to go to the Rio de las Palmas (near today's Tampico, Mexico) to start two towns. However, storms, strong currents, and winds pushed them north to present-day Florida. They landed near Boca Ciega Bay, about 15 miles north of Tampa Bay. Narváez decided this spot was not good for a settlement.

Narváez split his group. About 300 men went by land north along the coast. One hundred men and ten women went on the ships, also heading north. Narváez hoped the land and sea groups would meet at a large harbor further north. But they never met, as no such harbor existed.

As the land group marched, they faced many attacks from indigenous people. They also suffered from sickness and hunger. By September 1528, after trying to sail on makeshift rafts from Florida to Mexico, only 80 men were left. A storm swept them onto Galveston Island off the coast of Texas. The stranded survivors were captured and enslaved by indigenous groups. More men died due to the harsh conditions.

Only four people from the original group survived the next eight years. These were Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, Alonso del Castillo Maldonado, Andrés Dorantes de Carranza, and Dorantes' enslaved man, Estevanico. They wandered through what is now the Southwestern United States and northern Mexico. In 1536, they finally met Spanish slave-catchers in Sinaloa. From there, the four men reached Mexico City.

When Cabeza de Vaca returned to Spain, he wrote about the expedition in his book La relación ("The Story"). It was published in 1542. This book was the first written account of the native peoples, animals, and plants of inland North America. It was later published again with the title Naufragios ("Shipwrecks").

Contents

The Start of the Journey

On December 25, 1526, Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, who was also King Carlos I of Spain, gave Pánfilo de Narváez permission. This permission allowed Narváez to claim what is now the Gulf Coast of the United States for Spain. The agreement gave him one year to gather an army and leave Spain. He also had to build at least two towns with a hundred people each. He also needed to set up two more forts along the coast. Narváez had to pay for the expedition himself. He found investors by promising them riches, like those Hernán Cortés had recently found in Mexico.

Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca was appointed by the Spanish Crown as treasurer and sheriff. He was like the king's eyes and ears, and he was second-in-command. His job was to make sure the Crown received one-fifth of any wealth found. Other members included Alonso de Solís, Alonso Enríquez, and an Aztec prince called Don Pedro. There were also priests, led by Padre Juan Suárez. Most of the expedition's 600 men were soldiers from Spain and Portugal. Some were of mixed African descent, and about 22 were from Italy.

The Expedition Begins

On June 17, 1527, the expedition left Spain from the port of Sanlúcar de Barrameda. This port is at the mouth of the Guadalquivir River. The group included about 450 soldiers, officers, and enslaved people. About 150 others were sailors, wives, and servants.

Their first stop was the Canary Islands, about a week's journey into the Atlantic Ocean. There, the expedition restocked supplies like water, wine, firewood, meat, and fruit.

Stops in Hispaniola and Cuba

The explorers arrived in Santo Domingo (Hispaniola) in August 1527. During their stay, soldiers started leaving the expedition. This was a common problem on such journeys. The men might have left because they heard about a recent expedition led by Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón. In that trip, 450 out of 600 men had died. Nearly 100 men left Narváez's expedition in the first month in Santo Domingo. The expedition stopped here to buy horses and two small ships. These ships were for exploring the coastline. Narváez could only buy one small ship, but he set sail again.

The expedition reached Santiago de Cuba in late September. Cuba was Narváez's home, so he had many friends there. He could get more supplies, horses, and men. Narváez sent part of the fleet to Trinidad to get horses and supplies from his friend's estate.

Narváez put Cabeza de Vaca and a captain named Pantoja in charge of two ships going to Trinidad. Narváez took the other four ships to the Gulf of Guacanayabo. Around October 30, the two ships arrived in Trinidad to collect supplies and find more crew. A hurricane hit shortly after they arrived. Both ships sank during the storm. Sixty men died, a fifth of the horses drowned, and all the new supplies were lost.

Narváez realized they needed to regroup. He sent the four remaining ships to Cienfuegos under Cabeza de Vaca's command. Narváez stayed on land to find more men and buy more ships. After almost four months, on February 20, 1528, he arrived in Cienfuegos. He had one of two new ships and a few more recruits. He sent the other new ship to Havana. At this point, the expedition had about 400 men and 80 horses. The winter delay used up many supplies. They planned to get more in Havana on their way to Florida.

Narváez hired a skilled pilot named Diego Miruelo. He claimed to know a lot about the Gulf Coast. Historians have long wondered about his true identity and how much he really knew. Two days after leaving Cienfuegos, every ship in the fleet got stuck on the Canarreos shoals near Cuba. They were stuck for two to three weeks, using up their already low supplies. They could not escape the shoals until the second week of March, when a storm created large waves.

After battling more storms, the expedition sailed around the western tip of Cuba. They then headed toward Havana. They were close enough to see ships in the port. But the wind blew the fleet into the Gulf of Mexico before they could reach Havana. Narváez decided to continue with the journey and colonization plans. They spent the next month trying to reach the Mexican coast. However, they could not get past the strong current of the Gulf Stream.

Landing in Florida

On April 12, 1528, the expedition saw land north of what is now Tampa Bay. They turned south and sailed for two days. They were looking for a great harbor that the pilot Miruelo had described. During these two days, one of their five remaining ships was lost. Finally, after seeing a shallow bay, Narváez ordered them to enter. They sailed into Boca Ciega Bay, north of the entrance to Tampa Bay. They saw buildings on earthen mounds. These were good signs of culture, food, and water. The native people there were later identified as members of the Safety Harbor culture. The Spaniards dropped anchor and got ready to go ashore. Narváez landed with 300 men in Boca Ciega Bay. This spot is now known as the Jungle Prada Site in St. Petersburg.

Alonso Enríquez, the comptroller, was one of the first to land. He went to the nearby native village. He traded items like glass beads, brass bells, and cloth for fresh fish and deer meat. Narváez ordered the rest of the group to land and set up a camp.

The next day, the royal officials gathered on shore. They formally declared Narváez as the royal governor of La Florida. He read (in Spanish) the Requerimiento. This document told any natives listening that their land belonged to Charles V by order of the Pope. It also said that natives could choose to become Christians. If they converted, they would be welcomed. If they chose not to, war would be made against them. The expedition ignored both pleas and threats from a group of natives the next day.

After some exploring, Narváez and other officers found Old Tampa Bay. They went back to camp and told Miruelo to pilot a brigantine (a small ship) to find the great harbor he had spoken about. If he failed, he was to return to Cuba. Narváez never heard from Miruelo or the brig's crew again.

Meanwhile, Narváez took another group inland. They found another village, possibly Tocobaga. The villagers were using Spanish shipping boxes as coffins. The Spanish destroyed these and found a little food and gold. The local people told them there was plenty of both in Apalachee to the north. After returning to their base camp, the Spanish planned to head north.

Narváez Divides His Forces

On May 1, 1528, Narváez decided to split the expedition into land and sea groups. He planned for an army of 300 men to march north by land. The ships, with the remaining 100 people, would sail up the coast to meet them. He thought the mouth of Tampa Bay was a short distance north. But it was actually to the south. Cabeza de Vaca argued against this plan, but the other officers outvoted him. Narváez wanted Cabeza de Vaca to lead the sea group, but he refused. He later wrote that it was a matter of honor, as Narváez had suggested he was a coward.

The men marched for two weeks, almost starving. They then found a village north of the Withlacoochee River. They enslaved the natives and took corn from their fields for three days. They sent two groups to explore downstream on both sides of the river. They were looking for signs of the ships, but found none. Narváez ordered the group to continue north to Apalachee.

Years later, Cabeza de Vaca learned what happened to the ships. Miruelo had returned to Old Tampa Bay in the brigantine. He found all the ships gone. He sailed to Havana to pick up the fifth ship, which had been supplied. He brought it back to Tampa Bay. After heading north for some time without finding the land party, the commanders of the other three ships decided to return to Tampa Bay. After meeting, the fleet searched for the land party for almost a year. Then they finally left for Mexico. Juan Ortiz, a member of the naval force, was captured by the Uzita. He later escaped to Mocoso, where he lived until Hernando de Soto's expedition rescued him.

Meeting the Timucua People

Scouts told the Timucua people that the Spanish group was getting close to their land. They decided to meet the Europeans on June 18. Narváez used hand signs and gestures to tell their chief, Dulchanchellin, that they were going to Apalachee. Dulchanchellin seemed happy about this, as the Apalachee were his enemies.

The two leaders exchanged gifts. Then the expedition followed the Timucua into their land and crossed the Suwannee River. During the crossing, an officer named Juan Velázquez rode his horse into the river, and both drowned. This was the first death not caused by a shipwreck, and the men were upset. The starving army cooked and ate his horse that night.

When the Spaniards arrived at the Timucua village on June 19, the chief gave them corn. That night, an arrow was shot past one of Narváez's men near a watering hole. The next morning, the Spaniards found that the natives had left the village. They set out again for Apalachee. They soon realized that hostile natives were following them. Narváez set a trap for the natives chasing them. They captured three or four, whom they used as guides. The Spanish had no more contact with those Timucua.

Challenges in Apalachee

On June 25, 1528, the expedition entered Apalachee territory. They found a community of forty houses. They thought it was the capital, but it was a small village of a much larger culture. The Spanish attacked, took several hostages, including the village's cacique (chief), and took over the village. The villagers did not have the gold and riches Narváez expected. But they did have a lot of corn.

Soon after Narváez took the village, Apalachee warriors started attacking the Europeans. Their first attack was with 200 warriors. They used burning arrows to set fire to the houses the Europeans were in. The warriors quickly scattered, losing only one man. The next day, another 200 warriors, with large bows, attacked from the other side of the village. This group also quickly scattered and lost only one man.

After these direct attacks, the Apalachee changed their methods. They used quick attacks after the Spanish started marching again. They could fire their bows five or six times while the Spanish loaded a crossbow or harquebus. Then they would disappear into the woods. They bothered the Spanish with guerrilla tactics for the next three weeks. During this time, Narváez sent out three scouting missions. They were looking for larger or richer towns. All three came back with no good news. Narváez was frustrated by bad luck and poor health. He ordered the expedition to head south. The Apalachee and Timucua captives told him that the people of Aute had a lot of food. Their village was also near the sea. The group had to cross a large swamp to reach the place.

For the first two days out of the village, the Spaniards were not attacked. But once they were chest-deep in water in the swamp, the Apalachee attacked them with a shower of arrows. The Spanish were almost helpless. They could not use their horses or quickly reload their heavy weapons. Their armor weighed them down in the water. After reaching solid ground, they drove off the attackers. For the next two weeks, they struggled through the swamp. They were occasionally attacked by the Apalachee.

When the Spanish finally reached Aute, they found the village empty and burned. They gathered enough corn, beans, and squash from the garden to feed their group. Many of them were starving, wounded, and sick. After two days, Narváez sent Cabeza de Vaca to look for a way to the sea. He did not find the sea. But after half a day's march along the Wakulla River and St. Marks River, he found shallow, salty water with many oyster beds. Two more days of scouting showed no better results. The men returned to tell Narváez the news.

Narváez decided to go to the oyster beds for food. Many of the horses were carrying the sick and wounded. The Spanish realized they were fighting for survival. During the march, some of the caballeros (knights) talked about stealing their horses and leaving everyone else. Narváez was too ill to act. But Cabeza de Vaca learned of the plan and convinced them to stay.

After a few days stuck near the shallow waters, one man came up with a plan. He suggested melting down their weapons and armor. They could make tools and build new boats to sail to Mexico. The group agreed and started on August 4, 1528.

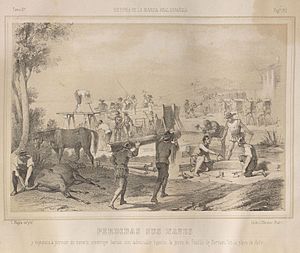

They built a forge from a log and used deerskins for the bellows. They cut down trees and made charcoal for the forge. Then they made hammers, saws, axes, and nails from their iron gear. They made caulking from the pitch of pine trees. Palmetto leaves were used as oakum (material for sealing boat seams). They sewed shirts together for sails. Sometimes they raided the Aute village. From there, they stole 640 bushels of corn to eat while building the boats. Twice, within sight of the camp, ten men gathering shellfish were killed by Apalachee raids.

The men killed their horses for food and materials while building the boats. They killed one horse every three days. They used horsehair to braid rope and the skins for water storage bags. Horses were very valuable to the Spanish, especially the nobles. So, they named the bay, now known as Apalachee Bay, "Bahia de los Caballos" (Bay of Horses). This was to honor the animals' sacrifice.

By September 20, they had finished building five boats. They sailed on September 22, 1528. After being hit by sickness, hunger, and attacks, 242 men had survived. About 50 men were carried by each boat. The boats were thirty to forty feet long. They had a shallow bottom, a sail, and oars.

Journey Through South Texas

The boats followed the Gulf Coast closely, heading west. But frequent storms, thirst, and hunger reduced the expedition to about 80 survivors. Then a hurricane threw Cabeza de Vaca and his remaining men onto the western shore of a barrier island. There, they suffered from hunger and disease. They named the island the "island of misfortune" or "island of ill fortune." Historians believe they landed at present-day Galveston, Texas. However, some historians point out differences between Cabeza de Vaca's description and Galveston Island. Many now think it's more likely they landed at what is now Follet's Island, just southwest of Galveston Island.

For the next four years, Cabeza de Vaca and a shrinking number of his friends lived among the complex native groups of South Texas. Tribes with different cultures and languages often fought each other. Cabeza de Vaca wrote detailed notes about the customs and culture of the people he met. He mentioned a few tribes that modern researchers have identified, like the Karankawa people along the Gulf Coast and the Tonkawa in central Texas. However, most tribe names in his book are not found in other writings. This makes it hard to link them to other known tribes.

Across Southwestern North America

By 1532, only four members of the original expedition were left: Alonso del Castillo Maldonado, Andrés Dorantes de Carranza, Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, and Estevanico, an enslaved man from Morocco. They headed west and then gradually south. They hoped to reach the Spanish Empire's outpost in Mexico. They became the first people from Europe and Africa to enter Southwestern North America. This area includes parts of today's Southwestern United States and Northwest Mexico.

Their exact path has been hard for historians to figure out. But they likely traveled across present-day Texas, perhaps into New Mexico and Arizona. They also went through Mexico's northern areas near the Pacific Coast before turning inland.

In July 1536, near Culiacán in present-day Sinaloa, the survivors met other Spaniards. These Spaniards were on a trip to capture people to make them slaves for New Spain. As Cabeza de Vaca later wrote, his countrymen were "dumbfounded at the sight of me, strangely dressed and in the company of Indians. They just stood staring for a long time." The Spaniards took the survivors to Mexico City. Estevanico later became a guide for other expeditions. Cabeza de Vaca returned to Spain. There, he wrote a full account, especially describing the many native peoples they met. He later worked for the colonial government in South America.

The Expedition in Stories

The Moor's Account, a novel from 2014 by Laila Lalami, is a made-up story from the viewpoint of Estevanico. He was the Moroccan enslaved man who survived the expedition with Cabeza de Vaca. He is known as the first black explorer of America. Lalami explains that not much is known about him, except for one line in Cabeza de Vaca's book. It says: "The fourth [survivor] is Estevanico, an Arab Negro from Azamor." The book was a finalist for the 2015 Pulitzer Prize in fiction.

A Land So Strange, a 2007 historical book by Andrés Reséndez, tells the journey again for today's readers. It uses original writings by Cabeza de Vaca and the official report. Esteban: The African Slave Who Explored America, a 2018 nonfiction book by Dennis Herrick, corrects old myths and mistakes about the African explorer. The Gentle Conquistadors, a 1971 novel by Jeannette Mirsky, gives a somewhat fictional account of the expedition.

See also

In Spanish: Expedición de Narváez para niños

In Spanish: Expedición de Narváez para niños

- Hernando de Soto, Narváez's successor

- Mocoso

| Bessie Coleman |

| Spann Watson |

| Jill E. Brown |

| Sherman W. White |