Queen Anne's War facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Queen Anne's War |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of the Spanish Succession and the Indian Wars | ||||||||||

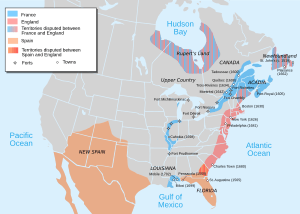

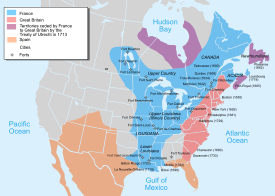

Map of European colonies in America, 1702 |

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

| Belligerents | ||||||||||

|

Caughnawaga Mohawk Choctaw Timucua Apalachee Natchez |

Chickasaw Yamasee |

|||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | ||||||||||

| José de Zúñiga y la Cerda Daniel d'Auger de Subercase Philippe de Rigaud Vaudreuil Father Sebastian Rale Jean-Baptiste Hertel de Rouville |

Joseph Dudley James Moore Francis Nicholson Hovenden Walker Benjamin Church |

|||||||||

Queen Anne's War (1702–1713) was a major conflict in North America. It was the second in a series of French and Indian Wars. This war involved the colonial empires of Great Britain, France, and Spain. It happened during the time when Anne, Queen of Great Britain was queen. In Europe, this war was part of the War of the Spanish Succession. In the Americas, it is often seen as a separate conflict. It is also known as the Third Indian War or the Second Intercolonial War in France.

Contents

Key Events of the War

The war started in 1701. It was mainly a fight between French, Spanish, and English colonists. They were all trying to control the North American continent. At the same time, the War of the Spanish Succession was happening in Europe. Each side in North America had different Native American tribes as allies. The fighting took place in four main areas:

- In the south, Spanish Florida and the English Province of Carolina attacked each other. English colonists also fought French colonists near Mobile, Alabama. Native American groups helped both sides. This southern fighting did not change who controlled the land much. However, it greatly reduced the Native American population in Spanish Florida. It also destroyed the Spanish missions in Florida.

- In New England, English colonists and their Native American allies fought against French colonists and their Native American forces. This happened especially in Acadia and along the border with Canada. The British colonists tried to capture Quebec City several times. In 1710, they successfully captured Port Royal, the capital of Acadia. French colonists and the Wabanaki Confederacy wanted to stop British expansion into Acadia. They believed the border was the Kennebec River in what is now southern Maine. They carried out raids in the Province of Massachusetts Bay. Famous raids include the Raid on Deerfield in 1704. Many people were captured and taken to Montreal or Kahnawake. Some were later ransomed, and some children were adopted by Mohawk families.

- In Newfoundland, English colonists at St. John's fought for control of the island with French colonists from Plaisance. Most of the fighting involved raids that harmed the economy. The French colonists captured St. John's in 1709. But the British quickly took it back after the French left.

- French privateers (private ships allowed to attack enemy ships) from Acadia and Plaisance captured many ships. These ships belonged to New England's fishing and shipping industries. The naval fighting ended when the British captured Acadia (Nova Scotia).

The Treaty of Utrecht officially ended the war in 1713. France gave the territories of Hudson Bay, Acadia, and Newfoundland to Britain. France kept Cape Breton Island and other islands in the Gulf of Saint Lawrence. Some parts of the treaty were not very clear. Also, the concerns of various Native American tribes were not included. This led to more conflicts later on.

Why the War Started

War began in Europe in 1701 after King Charles II died. The fight was about who would become the next king of Spain. At first, only a few European countries were involved. But in May 1702, England declared war on Spain and France. Both Britain and France wanted their American colonies to stay neutral. However, they could not agree on this.

The American colonists already had their own problems. Tensions were growing along the borders between French and English colonies. They worried about land boundaries and who had authority. This was true in the northern and southwestern parts of the English colonies. These colonies stretched from Province of Carolina in the south to Province of Massachusetts Bay in the north. There were also settlements in Newfoundland and at Hudson Bay.

The English colonies had about 250,000 people. Most lived in Virginia and New England. Colonists lived mainly along the coast. Some small settlements were inland, sometimes reaching the Appalachian Mountains. They knew little about the land west of the Appalachians and south of the Great Lakes. This area was home to many Native American tribes. French and English traders had visited these areas.

Spanish missionaries in La Florida had built missions. They wanted to convert Native Americans to Catholicism and use their labor. The Spanish population was small, about 1,500 people. The Native American population they worked with was around 20,000.

French colonists arrived in the south. This threatened the trade routes that Carolina colonists had built inland. This caused tension among all three powers. France and Spain were allies in this war. But they had been enemies in the recent Nine Years' War. Carolina and Florida also had disagreements over land south of the Savannah River. There was also religious conflict between Catholic Spanish colonists and Protestant English colonists.

In the north, the conflict was about land and money. Newfoundland had a British colony at St. John's and a French colony at Plaisance. Both sides also had smaller settlements. Many seasonal fishermen from Europe used the island. There were fewer than 2,000 English and 1,000 French permanent settlers. They competed for the fish in the Grand Banks of Newfoundland. Fishermen from Acadia and Massachusetts also used these fishing grounds.

The borders between Acadia and New England were unclear. This was true even after battles during King William's War. New France said Acadia's border was the Kennebec River in southern Maine. Catholic missions at Norridgewock and Penobscot were bases for attacks on New England settlers. These settlers were moving towards Acadia. The areas between the Saint Lawrence River and the coastal settlements of Massachusetts and New York were mostly controlled by Native Americans. These were mainly Abenaki in the east and Iroquois west of the Hudson River. The Hudson River–Lake Champlain area had also been used for raids in earlier wars. The threat from Native Americans had lessened due to disease and the last war. But they still posed a danger to faraway settlements.

The Hudson Bay territories were not a major battleground in this war. French and English companies had fought over them since the 1680s. But the 1697 Treaty of Ryswick left France in control of most outposts. The only notable event was a French attack on Fort Albany in 1709. The Hudson's Bay Company wanted its territories back. They successfully asked for them during the peace talks that ended this war.

Military Tools and Organization

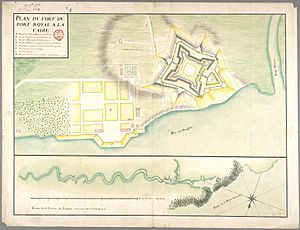

Colonial military technology in North America was not as advanced as in Europe. Only a few colonial settlements had stone forts at the start of the war. These included St. Augustine, Florida, Boston, Quebec City, and St. John's, Newfoundland and Labrador. However, Port Royal's stone defenses were finished early in the war. Some villages were protected by wooden walls called palisades. Many had only strong wooden houses with holes for firing guns. They also had overhanging second floors to shoot down at attackers.

Europeans and colonists usually had smooth-bore muskets. These guns could shoot about 100 yards (91 meters). But they were not accurate beyond half that distance. Some colonists also carried long spears called pikes. Native American warriors used weapons given by colonists or their own tools like tomahawks and bows. A few colonists knew how to use cannons. Cannons were the only effective weapons against strong stone or wooden defenses.

English colonists were generally organized into local groups called militias. Their colonies had no regular army, except for a few soldiers in Newfoundland. French colonists also had militias. But they also had a standing army called the troupes de la marine. This force had experienced officers and recruits from France. It numbered between 500 and 1,200 soldiers. They were spread across New France, mostly in major towns. Spanish Florida was defended by a few hundred regular troops. Spanish policy was to keep Native Americans in their territory peaceful. They did not give them weapons. Florida had about 8,000 Native Americans before the war. This number dropped to 200 after English colonist raids early in the war.

How the War Unfolded

Fighting in Carolina and Florida

Important French and English colonists knew that controlling the Mississippi River would be key for future trade. Each side made plans to stop the other. French Canadian explorer Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville had a plan after the previous war. He wanted to make friends with Native Americans in the Mississippi area. Then he would use these friendships to push English colonists off the continent. Or at least, he wanted to limit them to coastal areas. To do this, he found the mouth of the Mississippi again in 1699. He then built Fort Maurepas near Biloxi, Mississippi. From there, and from Fort Louis de la Mobile (founded in 1702), he started making friends with the local Choctaw, Chickasaw, and Natchez tribes.

English traders from Carolina had built a large trading network. It reached across the southeastern part of the continent all the way to the Mississippi. Their leaders did not respect the Spanish in Florida. But they understood the threat from the French arriving on the coast. Both Carolina Governor Joseph Blake and his successor James Moore wanted to expand south and west. This would be at the expense of French and Spanish interests.

Iberville had talked to the Spanish in January 1702, before the war started in Europe. He suggested arming the Apalachee warriors and sending them against the English colonists. The Spanish sent an expedition led by Francisco Romo de Uriza. It left Pensacola, Florida in August for Carolina's trading centers. The English colonists knew about the expedition beforehand. They set up a defense at the Flint River. There, they defeated the Spanish-led force. They captured or killed about 500 Native Americans allied with the Spanish.

Carolina's Governor Moore learned about the fighting. He organized a force and led it against Spanish Florida. 500 English colonial soldiers and 300 Native Americans captured and burned the town of St. Augustine, Florida. This happened during the Siege of St. Augustine (1702). The English could not take the main fort. They left when a Spanish fleet arrived from Havana. In 1706, Carolina successfully fought off an attack on Charles Town. This attack was by a combined Spanish and French force from Havana.

The Apalachee and Timucua people of Spanish Florida were greatly impacted by a raiding expedition led by Moore in 1704. Many survivors were moved to the Savannah River and lived on reservations. Raids continued in the following years. These often involved large Native American forces, sometimes with a few white men. Major attacks were aimed at Pensacola in 1707 and Mobile in 1709. The Muscogee (Creek), Yamasee, and Chickasaw were armed and led by English colonists. They won these conflicts against the Choctaw, Timucua, and Apalachee.

Fighting in Acadia and New England

Throughout the war, New France and the Wabanaki Confederacy stopped New England from expanding into Acadia. New France said Acadia's border was the Kennebec River in southern Maine. In 1703, Michel Leneuf de la Vallière de Beaubassin led French Canadians and 500 Native Americans of the Wabanaki Confederacy. They attacked New England settlements from Wells to Falmouth (Portland, Maine). This was part of the Northeast Coast Campaign. They killed or captured more than 300 settlers.

There were also raids deep into New England by French and Native American forces. Their goal was to take captives. There was a system for trading captives. Families and communities worked hard to raise money to get their loved ones back. In February 1704, Jean-Baptiste Hertel de Rouville led 250 Abenaki and Caughnawaga Indians (mostly Mohawk) and 50 French Canadians. They raided Deerfield in the Province of Massachusetts Bay. They destroyed the settlement, killed many, and captured over 100 people. These captives were taken hundreds of miles north to the Caughnawaga mission village near Montreal. Most children who survived the journey were adopted by Mohawk families. Some adults were later ransomed or released in prisoner exchanges. The minister, Williams, tried for years to ransom his daughter, but she became fully part of the Mohawk community and married a Mohawk man. In August 1704, there was also a raid in Marlborough. Captives were taken to Caughnawaga from there too. Communities raised money to ransom their citizens from Native American captivity. For example, a captured boy, Ashur Rice, was returned to Marlborough after his father ransomed him in 1708.

New England colonists could not stop these raids effectively. So, they fought back by sending an expedition against Acadia. It was led by the famous Native American fighter Benjamin Church. The expedition raided Grand Pré, Chignecto, and other settlements. French reports say Church tried to attack Acadia's capital of Port Royal. But Church's own report says the expedition decided not to attack.

Father Sébastien Rale was thought to be encouraging the Norridgewock tribe against the New Englanders. Massachusetts Governor Joseph Dudley offered a reward for his capture. In the winter of 1705, Massachusetts sent 275 militiamen to capture Rale and destroy the village. The priest was warned and escaped into the woods with his papers. But the militia burned the village and church.

French and Wabanaki Confederacy continued raiding northern Massachusetts in 1705. The New England colonists could not defend well against them. The raids happened too fast for defenses to be organized. And revenge raids usually found tribal camps empty. There was a break in the raids while leaders from New France and New England tried to exchange prisoners. They had only limited success. Raids by Native Americans continued until the end of the war, sometimes with French help.

In May 1707, Governor Dudley organized an expedition to take Port Royal. It was led by John March. However, 1,600 men failed to take the fort by siege. A second expedition in August was also pushed back. In response, the French planned a big raid on most of the New Hampshire settlements along the Piscataqua River. But much of the needed Native American support did not arrive. So, the Massachusetts town of Haverhill was raided instead. In 1709, New France governor Philippe de Rigaud Vaudreuil reported that two-thirds of the fields north of Boston were not being farmed. This was because of French and Native American raids. French-Native American war parties were returning without prisoners. This was because New England colonists stayed in their forts and would not come out.

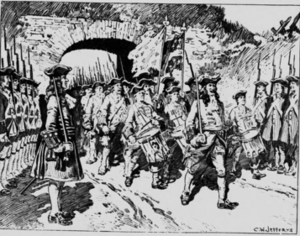

In October 1710, 3,600 British and colonial forces led by Francis Nicholson finally captured Port Royal. This happened after a one-week siege. This ended official French control of the peninsula part of Acadia (now mainland Nova Scotia). However, fighting continued until the end of the war. Resistance by the Wabanaki Confederation continued in the 1711 Battle of Bloody Creek and raids along the Maine border. The rest of Acadia (now eastern Maine and New Brunswick) remained disputed land between New England and New France.

Fighting in New France

The French in the main part of New France, Canada, did not want to attack the Province of New York. They were afraid of the Iroquois. They feared them more than the British colonists. They had made the Great Peace of Montreal with the Iroquois in 1701. New York merchants also did not want to attack New France. This would stop the profitable Native American fur trade, much of which came through New France. The Iroquois stayed neutral throughout the war. This was despite Peter Schuyler's attempts to get them involved. (Schuyler was Albany's commissioner for Native Americans.)

Francis Nicholson and Samuel Vetch planned a big attack against New France in 1709. They had some money and help from the queen. The plan was to attack Montreal by land through Lake Champlain. And a naval force would attack Quebec by sea. The land expedition reached the southern end of Lake Champlain. But it was called off because the promised naval support for Quebec never arrived. (Those forces were sent to help Portugal.) The Iroquois had vaguely promised to help. But they delayed sending support until it was clear the expedition would fail. After this failure, Nicholson and Schuyler went to London. They were joined by King Hendrick and other chiefs. They wanted to get more interest in the North American war. The Native American delegation caused a stir in London. Queen Anne met with them. Nicholson and Schuyler succeeded. The queen supported Nicholson's successful capture of Port Royal in 1710. With that success, Nicholson went back to England. He gained support for another attempt on Quebec in 1711.

The plan for 1711 again involved land and sea attacks. But its execution was a disaster. A fleet of 15 warships and transports carrying 5,000 troops arrived at Boston in June. This doubled the town's population and made it hard for the colony to provide supplies. The expedition sailed for Quebec at the end of July. But some ships crashed on the rocky shores near the mouth of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence in the fog. Over 700 troops were lost. Admiral Hovenden Walker called off the expedition. Meanwhile, Nicholson had left for Montreal by land. But he only reached Lake George when he heard about Walker's disaster. He also turned back. In this expedition, the Iroquois sent several hundred warriors to fight with the English colonists. But they also secretly warned the French about the expedition. They were playing both sides of the conflict.

Fighting in Newfoundland

Newfoundland's coast had small French and English communities. Some fishing stations were used seasonally by fishermen from Europe. Both sides had fortified their main towns. The French were at Plaisance on the western side of the Avalon Peninsula. The English were at St. John's and in Conception Bay. During King William's War, d'Iberville had destroyed most of the English communities in 1696–97. The island became a battleground again in 1702. In August of that year, an English fleet under Commodore John Leake attacked the French communities but did not try to take Plaisance. In the winter of 1705, Plaisance's French governor Daniel d'Auger de Subercase fought back. He led a combined French and Mi'kmaq expedition. They destroyed several English settlements and unsuccessfully attacked Fort William at St. John's. The French and their Native American allies continued to bother the English throughout the summer. They caused about £188,000 in damage to English properties. The English sent a fleet in 1706 that destroyed French fishing outposts on the island's northern coasts. In December 1708, a combined force of French, Canadian, and Mi'kmaq volunteers captured St. John's. They also destroyed its defenses. However, they did not have enough resources to hold the prize. So, they left it. St. John's was taken back and refortified by the English in 1709. (The same French expedition also tried to take Ferryland, but it successfully defended itself.)

English fleet commanders thought about attacking Plaisance in 1703 and 1711. But they never did. Admiral Walker considered it in 1711 after the disaster at the mouth of the St. Lawrence River.

End of the War

In 1712, Britain and France agreed to stop fighting. A final peace agreement was signed the next year. This was the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht. Under this treaty, Britain gained Acadia (which they renamed Nova Scotia). They also gained control over Newfoundland, the Hudson Bay region, and the Caribbean island of Saint Kitts. France recognized that Britain had authority over the Iroquois. They also agreed that trade with Native Americans further inland would be open to all nations. France kept all the islands in the Gulf of Saint Lawrence, including Cape Breton Island. They also kept fishing rights in the area, including rights to dry fish on the northern shore of Newfoundland.

By the later years of the war, many Abenakis were tired of the conflict. This was despite French pressure to keep raiding New England. However, the Treaty of Utrecht did not include Native American interests. Some Abenaki wanted to make peace with the New Englanders. Governor Dudley organized a big peace conference at Portsmouth, New Hampshire. In talks there and at Casco Bay, the Abenakis disagreed with British claims. The British said France had given them the land of eastern Maine and New Brunswick. But the Abenakis agreed to confirm the borders at the Kennebec River. They also agreed to government-run trading posts in their territory. The Treaty of Portsmouth was approved on July 13, 1713. Eight representatives from some Wabanaki Confederacy tribes signed it. However, it included language saying Britain had control over their land. Over the next year, other Abenaki tribal leaders also signed the treaty. But no Mi'kmaq ever signed it or any other treaty until 1726.

What Happened After the War

Acadia and Newfoundland

Losing Newfoundland and Acadia meant France had less presence on the Atlantic coast. French people from Newfoundland moved to Cape Breton Island. This created the colony of Île-Royale. France built the Fortress of Louisbourg there in the years that followed. This French presence, plus the right to use the Newfoundland shore, caused ongoing problems. French and British fishing interests continued to clash. This was not fully solved until the late 1700s. The war severely harmed Newfoundland's economy. Fishing fleets were much smaller. The British fishing fleet started to recover right after the peace. They tried to stop Spanish ships from fishing in Newfoundland waters, as they had before. However, many Spanish ships simply changed their flags to English ones to avoid British rules.

The British capture of Acadia had long-term effects on the Acadians and Mi'kmaq living there. Britain's control over Nova Scotia was weak at first. French and Mi'kmaq leaders used this to their advantage. British relations with the Mi'kmaq after the war were difficult. This was because Britain expanded in Nova Scotia and along the Maine coast. New Englanders moved into Abenaki lands, often breaking earlier treaties. Neither the Abenakis nor the Mi'kmaq were recognized in the Treaty of Utrecht. The 1713 Portsmouth treaty was understood differently by them than by the New Englanders. So, the Mi'kmaq and Abenakis resisted these moves onto their lands. This conflict grew, partly due to French people like Sébastien Rale. Eventually, it led to Father Rale's War (1722–1727).

British relations were also difficult with the Acadians, who were now under British rule. They refused repeated British demands to swear loyalty to the British crown. This eventually caused many Acadians to move to Île-Royale and Île-Saint-Jean (now Prince Edward Island). By the 1740s, French leaders like Father Jean-Louis Le Loutre organized a guerrilla war. Their Mi'kmaq allies helped them fight British attempts to expand Protestant settlements in Nova Scotia.

Disagreements also continued between France and Britain over Acadia's borders. The treaty's description of the boundaries was unclear. France insisted that only the Acadian peninsula (modern Nova Scotia, except Cape Breton Island) was included. They said they kept rights to modern New Brunswick. The disputes over Acadia led to open conflict during King George's War in the 1740s. These issues were not solved until the British took over all French North American territories in the Seven Years' War.

New England

Massachusetts and New Hampshire were on the front lines of the war. Yet, the New England colonies suffered less economic damage than other areas. Some war costs were balanced by the importance of Boston as a center for shipbuilding and trade. Also, the crown's military spending on the 1711 Quebec expedition brought in a lot of money.

Southern Colonies

Spanish Florida never fully recovered its economy or population from the war. It was given to Britain in the 1763 Treaty of Paris after the Seven Years' War. Native Americans who had been moved along the Atlantic coast were unhappy under British rule. This was also true for those who had been British allies in this war. This unhappiness led to the 1715 Yamasee War. This war was a major threat to South Carolina's survival. The loss of people in Spanish territories helped lead to the founding of the Province of Georgia in 1732. This new colony was on land that Spain had originally claimed, just like Carolina. James Moore took military action against the Tuscaroras of North Carolina in the Tuscarora War. This war began in 1711. Many Tuscaroras fled north as refugees to join their relatives, the Iroquois.

The war's economic costs were high in some southern English colonies. This included colonies that saw little fighting. Virginia, Maryland, and to a lesser extent, Pennsylvania, were hit hard. It cost a lot to ship their export products (mainly tobacco) to European markets. They also suffered because of several very bad harvests. South Carolina built up a large debt to pay for military operations.

Trade

The French did not fully follow the trade rules of the Treaty of Utrecht. They tried to stop English trade with distant Native American tribes. They also built Fort Niagara in Iroquois territory. French settlements continued to grow on the Gulf Coast. This included the settlement of New Orleans in 1718. There were also other (unsuccessful) attempts to expand into Spanish-controlled Texas and Florida. French trading networks spread across the continent along the rivers that flowed into the Gulf of Mexico. This renewed conflicts with both the British and the Spanish. Trading networks in the Mississippi River area, including the Ohio River valley, also brought the French into more contact with British trading networks. British colonial settlements were crossing the Appalachian Mountains. Disagreements over that land eventually led to war in 1754. This was when the French and Indian War began.

|

See also

In Spanish: Guerra de la reina Ana para niños

In Spanish: Guerra de la reina Ana para niños

| Stephanie Wilson |

| Charles Bolden |

| Ronald McNair |

| Frederick D. Gregory |