Dummer's War facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Dummer's War |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Indian Wars | |||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

Mohawk |

Abenaki Pequawket Miꞌkmaq Maliseet |

||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| William Dummer John Doucett Shadrach Walton Thomas Westbrook John Lovewell † Jeremiah Moulton Johnson Harmon |

Gray Lock Sebastian Rale † Father Joseph Aubery Chief Paugus † Chief Mog † Chief Wowurna |

||||||

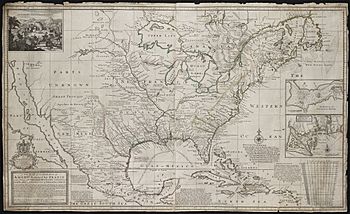

Dummer's War (1722–1725) was a series of fights between the New England Colonies and the Wabanaki Confederacy. The Wabanaki people included the Miꞌkmaq, Maliseet, and Abenaki tribes. They were allies of New France (which is now Canada).

This war is also known by many other names, like Father Rale's War or Lovewell's War. The fighting happened in two main areas. The eastern part was mostly along the border between New England and Acadia (in what is now Maine) and in Nova Scotia. The western part was in northern Massachusetts and Vermont. At that time, Maine and Vermont were part of Massachusetts.

The main reason for the conflict in Maine was a disagreement over the border. New France believed the border was the Kennebec River in southern Maine. After a war in 1710, mainland Nova Scotia came under British control. But parts of what are now New Brunswick and Maine were still fought over. France had Catholic missions in Native villages, like Norridgewock and Shubenacadie, Nova Scotia.

A peace treaty called the Treaty of Utrecht ended an earlier war in Europe. But this treaty didn't include the Wabanaki Confederacy. The Abenaki signed the 1713 Treaty of Portsmouth, but they weren't asked about British ownership of Nova Scotia. This led to the Miꞌkmaq attacking New England fishermen. The war started as New Englanders moved into Maine and Canso, Nova Scotia.

New Englanders were led by people like Lieutenant Governor William Dummer. The Wabanaki and other Native tribes were led by Father Sébastien Rale and Chief Gray Lock. During the war, Father Rale was killed. Many Native people moved away from the Kennebec and Penobscot rivers. This allowed New England to take control of more land in Maine.

Contents

Why the War Started

Dummer's War is sometimes called the Fourth Anglo-Abenaki War. There were three earlier wars involving Native Americans and the English colonists. These were King Philip's War (1675), King William's War, and Queen Anne's War (1703–1711).

The Treaty of Utrecht ended Queen Anne's War in 1713. This treaty changed the borders of northeastern America. But it didn't consider the land claims of the Native American tribes. French Acadia was given to Great Britain and became the province of Nova Scotia. However, its exact borders were still argued about.

The land that both European powers wanted was between the Kennebec River in eastern Maine and Isthmus of Chignecto in New Brunswick. This land was home to several Algonquian-speaking tribes. These tribes were loosely connected in the Wabanaki Confederacy. They believed they owned this land and had lived there for a long time.

The governor of Massachusetts, Joseph Dudley, held a peace meeting. The Wabanaki leaders said they didn't agree that the French could give their land to Britain. But they did agree to confirm the borders at the Kennebec River. They also agreed to have government trading posts in their territory. The Treaty of Portsmouth was signed by eight Wabanaki leaders in 1713. This treaty said that the British had power over their land. Other Abenaki leaders signed later, but no Miꞌkmaq leaders ever signed it.

Settlements and Forts Grow

After the peace treaty, New England settlements grew east of the Kennebec River. Many New Englanders also started fishing in Nova Scotia waters. They built a fishing village at Canso. This made the local Miꞌkmaq people upset, and they began to attack the settlement.

To respond to these attacks, Nova Scotia Governor Richard Philipps built a fort at Canso in 1720. Massachusetts governors also built forts near the Kennebec River. These included Fort George (1715) and Fort Richmond (1721). The French also built a church in the Abenaki village of Norridgewock. They also had a mission at Penobscot and a church in the Maliseet village of Meductic.

In 1717, Governor Shute met with Wabanaki leaders. They tried to agree on the land and trading posts. A Kennebec leader named Wiwurna said that the colonists were building settlements on their land. He said the Native people controlled the land. Governor Shute said the colonists had the right to expand. The Wabanaki wanted a clear border beyond which no new settlements would be allowed. Shute replied, "We desire only what is our own, and that we will have."

Over the next few years, New England colonists kept settling on Wabanaki lands. The Wabanaki responded by stealing farm animals. The Miꞌkmaq and French attacked Canso in 1720, making things worse. Governor Shute complained about a French priest, Sébastien Rale, who lived with the Kennebec tribe. Shute demanded that Rale be removed. The Wabanaki refused and asked for their hostages to be released.

The Wabanaki then wrote a document saying they owned the disputed areas. They threatened violence if their land was invaded. Shute called the letter "rude and threatening." He sent soldiers to Arrowsic. He also said that the Wabanaki claims were part of a French plan. He believed Father Rale was influencing them to help France claim the land.

Undeclared War Begins

Governor Shute believed the French were behind the Wabanaki claims. So, in January 1722, he sent soldiers to capture Father Rale. Most of the tribe was away hunting. The soldiers surrounded Norridgewock, but Rale was warned and escaped. However, they found his strongbox. Inside, they found letters that showed Rale was working for the Canadian government. The letters promised Native Americans ammunition to drive the colonists away.

Governor Shute wrote to the French governor, Philippe de Rigaud Vaudreuil. Shute repeated that the English owned the disputed areas. Vaudreuil replied that France claimed the area, but the Wabanaki still lived there. He suggested that Shute didn't understand how Native Americans viewed land ownership.

After the raid on Norridgewock, the Abenaki attacked Fort George on June 13. They burned homes and took 60 prisoners, but most were later released. On July 15, Father Lauverjat led 500 to 600 Native Americans from Penobscot and Medunic. They surrounded Fort St. George for 12 days. They burned buildings and killed cattle. Five New Englanders were killed, and seven were captured. The New Englanders killed 20 Maliseet and Penobscot warriors. After this, Brunswick was attacked and burned.

In response to the attack on Father Rale, 165 Miꞌkmaq and Maliseet fighters gathered. They planned to attack Annapolis Royal. Lieutenant Governor John Doucett took 22 Miꞌkmaq as hostages to stop the attack. In July, the Abenaki and Miꞌkmaq tried to starve Annapolis Royal. They captured 18 fishing boats and prisoners from Cape Sable Island to Canso.

On July 25, Governor Shute officially declared war on the Wabanaki. Lieutenant Governor William Dummer took charge of Massachusetts' part in the war. This was because Shute sailed to England to deal with problems with the Massachusetts assembly.

Fighting in the East (Maine and New Hampshire)

In September 1722, 400 to 500 Native Americans attacked Arrowsic, Maine. They were working with Father Rale. Captain Penhallow's small guard fought back, wounding three and killing one Native American. This allowed the villagers to get into the fort. The Native Americans then burned 26 houses and killed 50 cattle outside the fort. They attacked the fort but couldn't take it.

That night, Colonel Walton and Captain Harman arrived with 30 men. They joined 40 men from the fort. The combined force of 70 men attacked the Native Americans. But they were outnumbered and had to retreat back into the fort. The Native Americans eventually left, seeing no point in further attacks. On their way back, they attacked Fort Richmond. They burned homes and killed cattle, but the fort held. They also destroyed Brunswick and other settlements.

In March 1723, Colonel Thomas Westbrook led 230 men to the Penobscot River. They traveled about 32 miles upstream to the Penobscot Village. They found a large fort with 14-foot walls and 23 wigwams. There was also a large chapel. The village was empty, so the soldiers burned it down.

1723 Attacks

The Wabanaki Confederacy launched 14 raids against New England towns in 1723. Most of these were in Maine. The attacks started in April and lasted until December. During this time, 30 people were killed or captured. The attacks were so strong that Governor Dummer ordered people to move into blockhouses in the spring of 1724.

1724 Attacks

In the spring of 1724, the Wabanaki Confederacy made ten raids in Maine. More than 30 New Englanders were killed, wounded, or captured. They took a boat in Kennebunk harbor and killed everyone on board.

In the spring of 1724, Captain Josiah Winslow took command of St. George's Fort. On April 30, Winslow and Sergeant Harvey left the fort with 17 men in two boats. The next day, the boats separated. About 200 to 300 Abenaki attacked Harvey's boat. They killed Harvey and all his men, except for three Native American guides who escaped. Captain Winslow was then surrounded by 30 to 40 canoes. After hours of fighting, Winslow and his men were killed. Only three friendly Native Americans escaped back to the fort.

Native Americans killed one man and wounded another in Purpooduck on May 27. In June, Native Americans raided Dover, New Hampshire, and captured Elizabeth Hanson. They also used canoes to attack, with help from the Miꞌkmaq. In just a few weeks, they captured 22 boats, killed 22 New Englanders, and took more prisoners. They also tried to attack St. George's Fort but failed.

Battle of Norridgewock

In the second half of 1724, the New Englanders launched a strong attack. On August 22, captains Jeremiah Moulton and Johnson Harmon led 200 rangers to Norridgewock. Their goal was to kill Father Rale and destroy the village. There were 160 Abenaki people there. Many chose to run away instead of fighting. At least 31 chose to fight, and most of them were killed. Father Rale was killed at the start of the battle. A main chief was also killed, along with nearly two dozen women and children.

The colonists lost only two militiamen and one Mohawk warrior. Harmon destroyed the Abenaki farms. Those who escaped had to leave their village and move north to other Abenaki villages.

Lovewell's Raids

Captain John Lovewell led three trips against the Native Americans. On his first trip in December 1724, he and 30 men traveled north into the White Mountains of New Hampshire. On December 10, they killed two Abenaki. In February 1725, Lovewell went on a second trip. On February 20, his group found wigwams and killed ten Native Americans.

Battle of Pequawket

Lovewell's third trip started on April 16, 1725, with 46 men. They built a fort at Ossipee, New Hampshire and left 10 men there. The rest went to attack the Pequawket tribe at Fryeburg, Maine. On May 9, Lovewell's men saw a lone Abenaki warrior. They chased him, leaving their bags behind. A Pequawket war party, led by Chief Paugus, found the bags. They set up an ambush for when Lovewell's men returned.

Lovewell and his men caught the warrior and exchanged gunfire. Lovewell and one of his men were wounded, and the Native American was killed. When Lovewell's group returned to their bags, the ambush began. Lovewell and eight of his men were killed, and two were wounded. The Pequawkets opened fire. The survivors managed to get to a strong position. They fought off attacks until the Pequawkets left at sunset. Only 20 militiamen survived the battle. Three more died on the way back. Chief Paugus was among the Pequawket losses.

Fighting in the West (Vermont and Western Massachusetts)

The fighting in the west is also called "Grey Lock's War". On August 13, 1723, Chief Gray Lock entered the war. He raided Northfield, Massachusetts, where his warriors killed two people. The next day, they attacked Joseph Stevens and his four sons. Stevens escaped, two sons were killed, and two were captured. On October 9, Gray Lock attacked two small forts near Northfield. He caused injuries and took one captive.

In response, Governor Dummer ordered Fort Dummer to be built in Brattleboro, Vermont. This fort became a main base for scouting and attacks into Abenaki land. Fort Dummer was Vermont's first permanent settlement. On June 18, 1724, Gray Lock attacked men working near Hatfield, Massachusetts. He then killed men at Deerfield, Northfield, and Westfield. Governor Dummer sent more soldiers to these towns. On October 11, 1724, 70 Abenaki attacked Fort Dummer and killed three or four soldiers. In September 1725, Gray Lock and 14 others ambushed a scouting party from Fort Dummer. They killed two and captured three.

Fighting in Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia's governor tried to end the Miꞌkmaq blockade of Annapolis Royal in July 1722. They rescued over 86 New England prisoners. One battle, the Battle of Winnepang, resulted in 35 Native Americans and five New Englanders killed. During the war, a church was built at the Catholic mission in the Miꞌkmaq village of Shubenacadie. In 1723, Miꞌkmaq raided Canso, killing five fishermen. So, the New Englanders built a blockhouse with 12 guns to protect the village.

The worst moment for Annapolis Royal was on July 4, 1724. A group of 60 Miꞌkmaq and Maliseet raided the capital. They killed a sergeant and a private, wounded four soldiers, and scared the village. They also burned houses and took prisoners. The New Englanders responded by executing one of the Miꞌkmaq hostages. They also burned three Acadian houses. As a result, they built three blockhouses to protect the town. They moved the Acadian church closer to the fort so it could be watched. In 1725, 60 Abenaki and Miꞌkmaq attacked Canso again. They destroyed two houses and killed six people.

Peace Talks

Penobscot tribal chiefs said they wanted to talk peace in December 1724. French leaders didn't want peace and kept encouraging the fighting. But Massachusetts Lieutenant Governor Dummer announced that fighting would stop on July 31, 1725. This followed talks in March. Dummer and Chiefs Loron and Wenemouet worked out a first agreement. It only applied to the Penobscots at first. They were allowed to keep their Jesuit priests. But the two sides disagreed about land ownership and British control over the Wabanaki.

A French priest translated the agreement into Abenaki. Chief Loron immediately said he didn't agree with it. He especially rejected the idea of British control over him. Despite this disagreement, Loron still worked for peace. He sent peace messages to other tribal leaders. However, his messengers couldn't reach Gray Lock, who continued his raids.

Peace treaties were signed in Maine on December 15, 1725, and in Nova Scotia on June 15, 1726. Many tribal chiefs were involved. The peace was confirmed by everyone except Gray Lock at a large meeting in 1727. Other tribal messengers said they couldn't find him. Gray Lock's attacks stopped in 1727, and he is not mentioned in history after that.

What Happened After the War

After the war, the Native American population along the Kennebec and Penobscot Rivers decreased. Western Maine came more under British control. The terms of Dummer's Treaty were repeated at every new treaty meeting for the next 30 years. There wasn't another major conflict in the area until King George's War in the 1740s.

In New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, Dummer's Treaty changed how the British dealt with the Miꞌkmaq and Maliseet. These tribes refused to say they were British subjects. The French lost their strongholds in Maine. New Brunswick remained under French control for some years. The peace in Nova Scotia lasted for 18 years. The British took control of New Brunswick later. This war was the only one where the Wabanaki fought the British for their own reasons, not just to help the French.

The last major battle of the war was the Battle of Pequawket, also called "Lovewell's Fight." This battle was remembered in songs and stories in the 1800s. Famous writers like Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote about it. The town of Lovell, Maine is named after John Lovewell. Paugus Bay and Mount Paugus in New Hampshire are named after Chief Paugus. The site of the Norridgewock village is now a special historical place in Madison, Maine.

|

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |